Djedkare Isesi

| Djedkare Isesi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Djedkara, Izzj, Tankeris | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

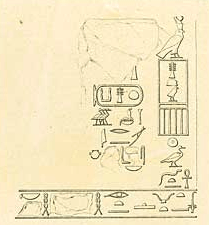

Relief of Djedkare Isesi, Egyptian Museum of Berlin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | Thirty-two to forty-three years of reign in the late-25th to mid-24th century BCE.[note 1] (Fifth Dynasty) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Menkauhor Kaiu | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Unas | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consort | possibly Meresankh IV? | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children |

Neserkauhor ♂, Kekheretnebti ♀, Meret-Isesi ♀, Hedjetnebu ♀, Nebtyemneferes ♀ Uncertain: Raemka ♂, Kaemtjenent ♂, Isesi-ankh ♂ Conjectural: Unas ♂ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Burial | Pyramid of Djedkare-Isesi | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Djedkare Isesi (known in Greek as Tancherês), was an Ancient Egyptian pharaoh, the eighth and penultimate ruler of the Fifth Dynasty in the late 25th century BCE to mid 24th century BCE, during the Old Kingdom period. He is assigned a reign of twenty-eight years by the Turin Canon although some Egyptologists believe this is an error and should rather be thirty-eight years. Manetho ascribes to him a reign of forty-four years while the archaeological evidence suggests that his reign is likely to have exceeded thirty-two years. Djedkare's prenomen or royal name means "The Soul of Ra Endureth."

Attestations

Historical sources

Djedkare is attested in three ancient Egyptian king lists, all dating to the New Kingdom.[17] Djedkare's prenomen occupies the 32nd entry of the Abydos King List, which was written during the reign of Seti I (1290–1279 BCE). Djedkare is also present on the Saqqara Tablet (31st entry)[16] where he is listed under the name "Maatkare", probably because of a scribal error.[18] Djedkare's prenomen is given as "Djed" on the Turin canon (third column, 24th row),[17] likely owing to a lacuna affecting the original document from which the canon was copied during the reign of Ramses II (1279–1213 BCE).[18] The Turin canon credits Djedkare with 28 years of reign.[2][18][19]

In addition to these sources, Djedkare is mentioned on the Prisse Papyrus dating to the 12th Dynasty (c. 1990–1800 BCE).[20] The papyrus records the The Maxims of Ptahhotep and gives Djedkare's nomen "Isesi" to name the pharaoh whom the authors of the maxims, vizier Ptahhotep, served.[21] Djedkare was also likely mentioned in the Aegyptiaca, a history of Egypt written in the 3rd century BCE during the reign of Ptolemy II (283–246 BCE) by the Egyptian priest Manetho. No copies of the Aegyptiaca have survived to this day and it is known to us only through later writings by Sextus Julius Africanus and Eusebius. Africanus relates that a pharaoh "Tancherês" (Ancient Greek Τανχέρης) reigned for 44 years as the eighth and penultimate king of the Fifth Dynasty.[22] Given its position within the dynasty, Tancherês is believed to be the Hellenized name of Djedkare Isesi.[17]

Contemporaneous sources

Djedkare is well attested in sources contemporaneous with his reign. The tombs of many of his courtiers have been discovered in Giza,[note 2] Saqqara and Abusir. They give insights in the administrative reforms that Djedkare conducted during his reign and, in a few cases, even record letters that the king sent to his officials.[30][31] These letters, inscribed on the walls of tombs, typically present royal praises for the tomb owner.[32]

Another important source of information concerning Egypt during the reign of Djedkare Isesi is the Abusir Papyri. These are administrative documents, covering a period of 24 years[33] during Djedkare's reign, were discovered in the mortuary temples of pharaohs Neferirkare Kakai, Neferefre and queen Khentkaus II.[34] In addition to these texts, the earliest letters on papyrus preserved to this day also date to Djedkare's reign, dealing with administrative or private matters.[33]

Family

Parents

Djedkare's parentage is unknown, in particular his relation with his predecessors Menkauhor Kaiu and Niuserre Ini cannot be ascertained.[36] Djedkare is generally thought to have been the son of Menkauhor Kaiu but the two might instead have been brothers and sons of Niuserre Ini.[37] In yet another hypothesis, Djedkare and Menkauhor could have been cousins,[37] being sons of Niuserre and Neferefre, respectively.[38] The identity of Djedkare's mother is similarly unknown.[39]

Queens

The name of Djedkare Isesi's principal wife is not known. An important queen consort was very likely the owner of the pyramid complex located to the northeast of Djedkare's pyramid in Saqqara.[40] Her high status could indicate that she was the mother of Djedkare's successor, Unas.[2] The queen's pyramid had an associated temple and it had its own satellite pyramid. The Egyptologist Klaus Baer suggested that the reworking of some of the reliefs may point to this queen ruling after the death of Djedkare, although this is rejected by other Egyptologists, such as Baud, owing to the lack of evidence for such a regency.[40] It is possible that this queen was the mother of Unas, but no conclusive evidence exists to support this theory.[39] The Egyptologist Wilfried Seipel has proposed that this pyramid was initially intended for queen Meresankh IV, whom he and Verner see as a wife of Djedkare.[39] Seipel contend that Meresankh was finally buried in a smaller mastaba in Saqqara North after she fell into disgrace.[41] Alternatively, Aidan Dodson and Dyan Hilton have proposed that she was a wife of the preceding king, Menkauhor Kaiu.[42]

Sons

Only one son of Djedkare Isesi has been identified for certain, Neserkauhor,[43] who bore the title of Eldest king's son of his body.[note 3][44] Neserkauhor also bore the title of Iry-pat, showing that he was an important member of the royal court, as well as a priestly title Greatest of the Five in the temple of Thot, suggesting that he may have been a vizier.[44]

In addition to Neserkauhor, there is indirect evidence that princes Raemka[note 4] and Kaemtjenent[note 5][47] are sons of Djedkare[48][49][50] based on the dating and general location of their tombs in Saqqara. For example, the tomb of Kaemtjenent mentions vizier Rashepses who served during the reign of Djedkare.[51][52] In addition, Raemka bore the title of King's son of his body,[45] almost exclusively reserved to true princes of royal blood.[note 6] Similar arguments have led Egyptologists to believe that both princes are sons[49] of queen Meresankh IV buried nearby, who would thus be one of Djedkare's wives.

A high official named Isesi-ankh could have been a son of Djedkare Isesi as well, as suggested by his name meaning "Isesi lives".[42] Yet, similarities in the titles and locations of the tombs[note 7] of Isesi-ankh and Kaemtjenent have led Egyptologists to propose that they could instead be brothers and sons of Meresankh IV,[54] or that the former is a son of the latter.[55] Even though Isesi-ankh bore the title of King's son, the Egyptologists Michel Baud and Bettina Schmitz argue that this filiation was fictitious, being only an honorary title.[56][57]

Finally, the successor of Djedkare, Unas, is thought to have been his son[2] in spite of the complete lack of evidence bearing on the question.[58] The main argument in favor of this filiation is that the succession from Djedkare Isesi to Unas seems to have been smooth.[59] In particular reliefs from Unas' causeway show many officials bearing basilophorous names incorporating "Isesi", suggesting at the very least that Unas did not perceive Djedkare as an antagonist.

Daughters

Several daughters of Djedkare Isesi have been identified by the title of King's daughter of his body and the general date of their tomb. These include Kekheretnebti,[note 8][42] whose filiation is clearly indicated by her additional title of Beloved of Isesi,[60] Meret-Isesi,[42][note 9] Hedjetnebu,[note 10][61][42] and Nebtyemneferes.[note 11][42] Less certain is the filiation of Kentkhaus III, wife of vizier Senedjemib Mehi, who bore the title of King's daughter of his body.[62][63] It is debated as to whether this title indicates a true filiation or if it is only honorary.[63][64]

Chronology

The relative chronological position of Djedkare Isesi as the eighth and penultimate ruler of the Fifth Dynasty, succeeding Menkauhor Kaiu and preceding Unas on the throne, is well established by historical sources and confirmed by archaeological evidence.[66] The duration of Djedkare's reign is less certain. While the Turin canon credits him with 28 years of reign, there is direct evidence in favor of a longer reign. One of the Abusir papyri is dated to the "Year of the 22nd Count, IV Akhet day 12", constituting Djedkare's highest known date.[67][note 13] This date might correspond to any time from the 32nd year of Djedkare's reign up to his 44th year on the throne, depending on whether the cattle count was biennial (once every two years), or was more regular, occuring once every year and a half. Djedkare Isesi's reign is well documented by the Abusir Papyri, numerous royal seals and contemporary inscriptions; taken together, they indicate a fairly long reign for this king.[69] Another element in favor of a long reign is an alabster vase E5323 on display at the Louvre museum celebrating Djedkare's first Sed festival, an event normally occurring 30 years after a king accession.

Reign

The reign of Djedkare Isesi heralds a new period in the history of the Old Kingdom.[70][71] First, Djedkare Isesi did not build a sun temple, as had done his predecessors since the time of Userkaf, some 80 years earlier.[72][73] This is possibly a consequence of the consolidation of the cult of Osiris during the late Fifth Dynasty.[1][74][75] The importance of this cult becomes manifest when the pyramid texts of the pyramid of Unas are inscribed a few decades later.[76][74] Another manifestation of the winds of change[77] during Djedkare's time on throne is the relocation of the royal necropolis from Abusir, where it had been since the reign of Sahure, to Saqqara where both Djedkare and his successor, Unas, built their pyramids. Abusir may have become overcrowed by the time of Djedkare's accession and the capital may have been shifted south to Saqqara along with the royal necropolis.[78]

Domestic reforms

Perhaps more significant are the reforms in the administration and priesthood that Djedkare effected.[79] These evolutions are witnessed by changes in priestly titles and more broadly, in the system of ranking titles of high officials, which was modified for the first time of its existence.[72] For example, the priesthood of the royal pyramids was reorganized,[1] with Djedkare changing the titles and functions of the priests from "priest of king" to "priest of the pyramid".[80] Princes of royal blood could once more hold administrative titles,[note 14] a prerogative which they had lost during the early Fifth Dynasty.[72] At the same time, viziers could now hold the prestigious titles of Iry-pat[71] and Haty-a[81] and, as Overseer of the royal scribes, became the head of the scribal administration.[82] At least one vizier, Seshemnefer III, even bore the title of King's son of his body, one of the most distinguished titles at the time and normally reserved to princes of royal blood. Yet neither Seshemnefer III's father nor his mother seem to have belonged to the royal family.[83] For the period spanning the reign of Djedkare until that of Teti, viziers were furthermore responsible of the weaponry of the state, both for military and other purposes.[83] Following the reforms undertaken by Djedkare, three viziers would be in office at the same time: two in the Memphite region and a Southern one, the Governor of Upper Egypt, in the province,[72] with a seat at Abydos.[1][2] In total six viziers were appointed during Djedkare's reign.[note 15][84]

At the opposite, lower ranking officials lost power during the late Fifth Dynasty and were frequently limited to holding only one high title, in rupture with the preceding period.[72] Such functions as Overseer of the granary and Overseer of the treasury disappear from the record some time between Djedkare's reign and that of Teti,[72] while men of lower status became head of the legal administration.[82] Consequently, the viziers concentrated more power than before while lower echelons of the state administration were reduced.[82]

For Nigel Strudwick, these reforms were undertaken as a reaction to the rapid growth of the central administration in the first part of the Fifth Dynasty[82] which, Baer adds, had amassed too much political or economic power[85] in the eyes of the king.[86] At the same time, the size of the provincial administration was increased,[2] while it also became more autonomous from the central government.[2] In particular, the nomarchs were responsible in their provinces for performing works hitherto conducted by Memphite officials.[82] Joyce Tyldesley thus sees the reign of Djedkare Isesi as the very beginning of a decline in the importance of the king, in conjunction with the gradual rise of the power wielded by the high and provincial administration.[87] Concurrent with this trend is a process of decentralization, with local loyalties slowly superseding allegiance to the central state.[87] Since offices and in particular, the vizierate, could be inherited[2] the reforms of Djedkare Isesi created a "virtual feudal system" as the Nicolas Grimal writes,[88][89] with much power in the hands of a few puissant officials. This is best witnessed by the large, magnificent mastaba tombs that Djedkare's viziers built.[88]

Building activities

The main building activity undertaken during the reign of Djedkare Isesi was the construction of his pyramid complex in Saqqara. In addition, Djedkare either completed or undertook restoration works in the funerary complex of Nyuserre Ini in Abusir, as indicated by a now damaged inscription[90] which must have detailed Djedkare's activities on the site.[note 16][92] Several relief decorated blocks with the name of the king were found reused in the pyramid of king Unas. Their original place remains unknown.[93]

Activities outside Egypt

Expeditions to mines and quarries

Three or four[note 17] rock inscriptions dating to Djedkare's reign have been found in the Wadi Maghareh in Sinai, where mines of copper and semi-precious stones were exploited throughout the Old Kingdom, from the Fourth until the Sixth Dynasty.[96] These inscriptions record three expeditions sent to look for turquoise: the earliest one, dated to the third[97] or fourth[98] cattle count–possibly corresponding to the sixth or eighth year of Dejdkare's reign–explicitely recalls the arrival of the mining party to the "hills of the turquoise"[note 18] after being given "divine authority for the finding of semi-precious stones in the writing of the god himself, [as was enacted] in the broad court of the temple Nekhenre".[97][98] This sentence could indicate the earliest known record of an oracular divination undertaken in order to ensure the success of the expedition prior to its departure, the Nekhenre being the sun temple of Userkaf.[98] Another inscription dating to the year of the ninth cattle count–possibly Djedkare's 18th year on the throne–shows the king "subduing all foreign lands. Smiting the chief of the foreign land".[97][98] The expedition that left this inscription comprised over 1400 men and administration officials.[100][101]

These expeditions departed Egypt from the port of Ain Sukhna, on the western shore of the Gulf of Suez, as revealed by papyri and seals bearing Djedkare Isesi's name found on the site.[102][103] The port comprised large galleries carved into the sandstone serving as living quarters and storage places.[103] The wall of one such gallery was inscribed with a text mentioning yet another expedition to the hills of turquoise in the year of the seventh cattle count–possibly Djedkare's 14th year on the throne.[104][99]

South of Egypt, Djedkare dispatched at least one expedition to the diorite quarries located 65 km (40 mi) north-west of Abu Simbel.[note 19][88] Djedkare was not the first king to do so, as these quarries were already exploited during the Fourth Dynasty and continued to be so during the Sixth Dynasty and later, in the Middle Kingdom period (c. 2055 BCE – c. 1650 BCE).[106]

Djedkare probably also exploited gold mines in the Eastern Desert and in Nubia: indeed, the earliest mention of the "land of gold"–an Ancient Egyptian term for Nubia[note 20]–is found in an inscription from the mortuary temple of Djedkare Isesi.[108]

Trade relations

Djedkare is known to have entairtained trade relations with Byblos. He also sent and expedition to the fabled land of Punt[88] to procure the myrrh used as incense in the Egyptian temples.[109] The expedition to Punt is referred to in the letter from Pepi II Neferkare to Harkuf some 100 years later. Harkuf had reported that he would bring back a "dwarf of the god's dancers from the land of the horizon dwellers". Pepi mentions that the god's sealbearer Werdjededkhnum had returned from Punt with a dwarf during the reign of Djedkare Isesi and had been richly rewarded. The decree mentions that "My Majesty will do for you something greater than what was done for the god's sealbearer Werdjededkhnum in the reign of Isesi, reflecting my majesty's yearning to see this dwarf".[110] Djedkare's expedition to Punt is also mentioned in a contemporaneous graffito found in Tumas, a locality of Lower Nubia some 150 km (93 mi) south of Aswan,[17] where Isesi's cartouche was discovered.[111]

A gold cylinder seal bearing the serekh of Djedkare Isesi together with the cartouche of Menkauhor Kaiu is now on display at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.[note 21][105] The seal, purportedly discovered near the Pactolus river valley in western Anatolia,[112] could attest to wide ranging trade-contacts during the later Fifth Dynasty,[2] but its provenance remains unverifiable.[note 22][114]

Warfare

Not all relations between Egypt and its neighbors were peaceful during Djedkare's reign. In particular, the earliest known depiction of a battle or city being besieged[115] is found in the tomb of Inti, an official from the 21st nome of Upper Egypt, who lived during the late Fifth Dynasty.[115][116] The scene shows Egyptian soldiers scaling the walls of a near eastern fortress on ladders.[117][17] More generally, ancient Egyptians seem to have regularly organised punitive raids in Canaan during the later Old Kingdom period but did not attempt to establish a permanent dominion there.[118]

Pyramid

Djedkare built his pyramid in South Saqqara. It was called Nefer Isesi or Nefer Djedkare in Ancient Egyptian,[119][note 23] meaning "Isesi/Djedkare is beautiful"[120] or "Isesi/Djedkare is perfect".[2][9] It is known today as Haram el-Shawwâf El-Kably,[119] meaning "the Southern Sentinel pyramid", because it stands on the edge of the Nile valley.[121]

The pyramid originally comprised six steps of irregular limestone blocks covered by white Tura limestone. At the time of its construction it stood 52 m (171 ft) high with a base length of 78.75 m (258.4 ft) and an inclination angle of 52°.

In the interior of the pyramid three rooms would have contained Djedkare's burial. The burial chamber contained the dark grey basalt sarcophagus which held the body of the king. The canopic jars were buried in the floor of the burial chamber, to the north-east of the sarcophagus. An antechamber and a storage chamber completed the set of interior rooms. Djedkare's almost complete mummy, along with a badly broken basalt sarcophagus and a niche for the canopic chest, was discovered in the pyramid.[39] An examination by A. Batrawi of the king's skeletal remains, found in the king's pyramid in the mid-1940s by Abdel Salam Hussein and A. Varille, suggests that Djedkare died at the age of 50 to 60 years old.[122][69]

To the east of the pyramid Djedkare's mortuary temple was laid out. The east facade of the mortuary temple featured two massive stone structures which resemble the later pylons. The mortuary temple is connected via a causeway to a valley temple. An interesting structure associated with Djedkare's pyramid is the so-called "Pyramid of the Unknown Queen". This pyramid complex lies at the south-east corner of Djedkare's complex.[39]

Legacy

Djedkare Isesi was the object of a funerary cult which lasted until the end of the Old Kingdom nearly 200 years after his death. Djedkare seem to have been held in high esteem during the reign of Merenre Nemtyemsaf I, who chose to place his pyramid complex close to that of Djedkare.[123] The South Saqqara Stone, a royal annal of the Sixth Dynasty dating to the reign of Merenre or of his successor Pepi II,[124] records rich offerings being made to Djedkare on behalf of the king.[note 24][125][126] Unfortunately, an estimated 92%[127] of the text inscribed on the stone was lost when it was roughly polished to be reused as a scarophagus lid, possibly in the late First Intermediate (c. 2160–2055 BC) to early Middle Kingdom period (c. 2055–1650 BC).[128]

More generally, an historical or literary tradition concerning events in the time of Djedkare seem to have flourished toward the end of Old Kigdom as can be inferred from the tombs of Harkuf and Iny.[129] These two officials were in charge of expeditions to foreign lands under Merenre I and Pepi II and both relate expeditions that took place during the time of Djedkare, in relation with their own travels which they report on the walls of their tombs.

Notes

- ↑ Proposed dates for Djedkare Isesi's reign: 2436–2404 BCE,[1][2][3] 2414–2375 BCE[4][5][6][7][8] 2405–2367 BCE,[9] 2380–2342 BCE,[10] 2379–2352 BCE,[11] 2365–2322 BCE.[12]

- ↑ Cemetery 2000 in Giza contains several tombs of overseers and inspectors of the palace attendants.[23] These people are thought to have held functions in the royal palace. The inspectors of the palace attendants include Redi (G 2086), Kapi (G 2091), and Pehenptah (G 2088). A courtier named Saib (G 2092+2093) was also a companion and held the positions of director of the palace. Saib was also secretary of the House of Morning. Saib was buried in a double mastaba. He may have shared this tomb with his wife Tjentet, who was a priestess of Neith. Nimaatre (G 2097) was another palace attendant of the Great House. Nimaatre may have been related to Saib, but this is not certain. Nimaatre also served as secretary of the Great House (i.e. the Palace). A man named Nefermesdjerkhufu (G 2240) was companion of the house, overseer of the department of palace attendants of the Great House, he who is in the heart of his lord, and secretary. He also held the positions of overseer of the two canals of the Great House, and he held a porition related to the royal documents.[24] A nobleman by the name of Kaemankh (G 4561) was royal acquaintance and was associated with the royal treasury. Kaemwankh was an inspector of administrators of the treasury, and secretary of the king's treasure.[25][26] Possibly one of the best known nobles from the time of Djedkare is his vizier Ptahhotep who was buried in Saqqara. Djedkare had another vizier by the name of Rashepses.[27] A letter directed to Rashepses has been preserved. This decree is inscribed in his tomb in Saqqara. Another well attested vizier was Senedjemib Inti. Senedjemib Inti was buried in Giza; in mastaba G 2370. He is described as true count Inti, chief justice and vizier Senedjemib, and the royal chamberlain Inti. Letters from Djedkare to his Vizier have been preserved because Senedjemib Inti had them inscribed in his tomb. One royal decree is addressed to the chief justice overseer of all works of the king and overseer of scribes of royal documents, Senedjemib. This decree mentions the planning of a court in the pool area(?) of the jubilee palace called "Lotus-of-Isesi". This decree is dated to either the 6th or 16th count, 4th month of the 3rd season, day 28. A second letter concerns a draft of the inscriptions of a structure called the "Sacred Marriage Chapel of Isesi". The third decree recorded in Inti's tomb mentions the construction of a lake.[28] Senedjemib Inti died during the reign of Djedkare Isesi. Inscriptions in the tomb of Inti describe how his son, Senedjemib Mehi, asks and receives permission to bring a sarcophagus from Tura. Senedjemib Mehi would later follow in his father's footsteps and become vizier during the reign of one of Djedkare's successors.[29]

- ↑ Neserkauhor was buried in mastaba C, south of Niuserre's pyramid complex in the east of the Abusir necropolis.[44]

- ↑ Prince Raemka was buried in the mastaba tomb S80, also known as mastaba D3 and QS 903, in Saqqara, north of Djoser's pyramid.[43] His tomb seems to have been usurped[45] from a certain Neferiretnes.[46] The chapel from Raemka's tomb is now on display in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[46]

- ↑ Prince Kaemtjenent was buried in the mastaba tomb S84 in Saqqara.[43]

- ↑ As opposed to those bearing the title King's son, which was used as an honorary title during the later Fifth Dynasty.

- ↑ Isesi-ankh was buried in mastaba D8, north of the pyramid of Djoser in Saqqara.[53]

- ↑ Kekheretnebti is believed to have died in her early thirties, she was buried in mastaba B in east Abusir, south of the pyramid complex of Niuserre.[60] She had a daughter named Tisethor who was buried in an extension of her tomb.[42]

- ↑ Probably buried in Abusir.[42]

- ↑ Buried in the mastaba K, south of Niuserre's complex in Abusir,[61] likely prior to the building of Tisethor's tomb.

- ↑ Buried in Abusir.[42]

- ↑ The inscription reads "First occasion of the Sed festival of the king of Upper and Lower Egypt Djedkare, beloved of the bas of Heliopolis, given life, stability, and all joy for ever.".[65]

- ↑ Miroslav Verner writes that Paule Posener-Kriéger and Jean-Louis de Cenival transcribed the year date numeral in the papyrus as the "year of the 21st count" in their 1968 study of the Abusir papyri.[68] However, Verner notes that in "the damaged place where the numeral still is, one can see a tiny black trace of another vertical stroke just visible. Therefore, the numeral can probably be reconstructed as 22.[67]

- ↑ The Egyptologist Nigel Strudwick illustrates this novelty with the cases of Isesi-ankh and Kaemtjenent, who both bore the title of King's son as well as a number of administrative titles such as Overseer of all the works of the King and Seal bearer of the God.[53] However the Egyptologists Michel Baud and Bettina Schmitz have argued that the title of King's son here does not denote a true filiation and was only honorary, at least in the case of Isesi-ankh.[57][56] More generally Baud and Schmitz consider that true princes of blood were qualified of smsw [z3 nswt] for "Eldest [king's son]" and remained excluded from holding administrative offices.[81]

- ↑ These are Ptahhotep Desher, Seshemnefer III, Ptahhotep, Rashepses, another Ptahhotep, and Senedjemib Inti.[84]

- ↑ The block inscribed with the text relating Djedkare's works in the temple of Nyuserre reads "Horus Djedkhau, the king of Upper and Lower Egypt, the Two Ladies Djedkhau, the Golden Horus Djed, Djedkare. For the king of Upper and Lower Egypt [Nyuse]rre he set up a monument ...".[90] It is now in the Berlin Museum, catalog No. 17933.[91]

- ↑ It is unclear whether two of the inscribed texts originate from the same damaged inscription or have always been part of two different inscriptions.[95]

- ↑ Also translated as "Terraces of turquoise" from the Egyptian ḫtjw mfk3t.[99]

- ↑ The rock exploited in these quarries actually comprises two varieties of gneiss, the word "diorite" being misused by Egyptologists to designate these.[106]

- ↑ Gold is Nub in Ancient Egyptian, and the "land of gold" may have given rise to the modern word "Nubia"[107]

- ↑ The golden seal has the catalog number 68.115.[105]

- ↑ The archaeologist Karin Sowada has even doubted the authenticity of the seal.[113]

- ↑ Transliterations nfr-Jzzj and nfr-Ḏd-k3-Rˁ.[119]

- ↑ See in particular the zone F6 of the Saqqara stone.[125]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Verner 2001b, p. 589.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Altenmüller 2001, p. 600.

- ↑ Hawass & Senussi 2008, p. 10.

- ↑ Malek 2000, p. 100.

- ↑ Rice 1999, pp. 46–47.

- ↑ Clayton 1994, pp. 60.

- ↑ Sowada & Grave 2009, p. 3.

- ↑ Lloyd 2010, p. xxxiv.

- 1 2 Strudwick 2005, p. xxx.

- ↑ von Beckerath 1999, pp. 60–61 & 283.

- ↑ Strudwick 1985, p. 3.

- ↑ Hornung 2012, p. 491.

- 1 2 3 4 Leprohon 2013, p. 40.

- ↑ Clayton 1994, p. 61.

- ↑ Leprohon 2013, p. 40, Footnote 63.

- 1 2 Mariette 1864, p. 15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Baker 2008, p. 84.

- 1 2 3 Baker 2008, p. 85.

- ↑ Gardiner 1959.

- ↑ Stevenson Smith 1971, p. 159.

- ↑ Horne 1917, pp. 62–78.

- ↑ Waddell 1971, p. 51.

- ↑ Ann Macy Roth, Giza Mastabas Volume 6, A Cemetery of Palace Attendants: Including G 2084–2099, G 2230+2231, and G 2240

- ↑ Ann Macy Roth, Giza Mastabas Volume 6

- ↑ http://gizapyramids.org/

- ↑ Porter and Moss, Volume III: Memphis

- ↑ Hayes 1978, p. 90.

- ↑ Wente 1990, pp. 18–20.

- ↑ Edward Brovarski, Giza Mastabas Vol. 7: The Senedjemib Complex

- ↑ Sethe 1903, pp. 59–65; 68; 179–180.

- ↑ Hayes 1978, p. 122.

- ↑ Thompson 2015, pp. 976–977.

- 1 2 Thompson 2015, p. 977.

- ↑ Papyrus Abu Sir, British Museum website 2016.

- ↑ Mariette 1885, p. 191.

- ↑ Dodson & Hilton 2004, p. 64.

- 1 2 Tyldesley 2005, p. 241.

- ↑ Verner 2002, p. 324.

- 1 2 3 4 5 M. Verner, The Pyramids, 1997

- 1 2 Baud 1999b, p. 624.

- ↑ Baud 1999b, p. 464.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Dodson & Hilton 2004, p. 68.

- 1 2 3 Dodson & Hilton 2004, p. 69.

- 1 2 3 Baud 1999b, p. 505.

- 1 2 Baud 1999b, p. 510.

- 1 2 Met. Museum of Art 2016.

- ↑ Brovarski 2001, p. 15.

- ↑ Dodson & Hilton 2004, pp. 68–69.

- 1 2 Baud 1999b, p. 591.

- ↑ Hayes 1978, p. 94.

- ↑ Schott 1977, pp. 443–461.

- ↑ Sethe 1903, pp. 181–186.

- 1 2 Baud 1999b, p. 421.

- ↑ Stevenson Smith 1971, pp. 187–188.

- ↑ Strudwick 1985, pp. 71–72.

- 1 2 Schmitz 1976, p. 88 & 90.

- 1 2 Baud 1999b, p. 422.

- ↑ Grimal 1992, p. 80.

- ↑ Baud 1999b, p. 563.

- 1 2 Baud 1999b, p. 561.

- 1 2 Baud 1999b, p. 486.

- ↑ Brovarski 2001, p. 30.

- 1 2 Baud 1999b, p. 555.

- ↑ Schmitz 1976, p. 119 & 123.

- ↑ Strudwick 2005, p. 130.

- ↑ von Beckerath 1999, pp. 60–61, king no. 8.

- 1 2 Verner 2001a, p. 406.

- ↑ Posener-Kriéger & de Cenival 1968, Plates 41 & 41A.

- 1 2 Verner 2001a, p. 410.

- ↑ Brovarski 2001, p. 23.

- 1 2 Andrassy 2008, p. 38.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Strudwick 1985, p. 339.

- ↑ Malek 2000, p. 99.

- 1 2 Dorman 2015.

- ↑ Kanawati 2003, p. 147.

- ↑ Tyldesley 2005, p. 240.

- ↑ Malek 2000, p. 102.

- ↑ Goelet 2015, p. 87.

- ↑ Strudwick 1985, p. 307 & 339.

- ↑ Baer 1960, p. 297.

- 1 2 Baud 1999a, p. 328.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Strudwick 1985, p. 340.

- 1 2 Kanawati 2003, p. 154.

- 1 2 Strudwick 1985, p. 301.

- ↑ Strudwick 1985, p. 341.

- ↑ Baer 1960, p. 297 & 300.

- 1 2 Tyldesley 2005, p. 238.

- 1 2 3 4 Grimal 1992, p. 79.

- ↑ Sicker 2000, p. 12.

- 1 2 Strudwick 2005, p. 94.

- ↑ Borchardt 1907, pp. 157–158, fig. 131.

- ↑ Morales 2006, p. 317.

- ↑ Labrousse, Lauer & Leclant 1977, pp. 125–128.

- ↑ Lepsius Denkmäler II, p. 2 & 39.

- ↑ Strudwick 2005, pp. 137–138, Texts C and D.

- ↑ Mumford 2015, pp. 1071–1072.

- 1 2 3 Mumford 2015, p. 1072.

- 1 2 3 4 Strudwick 2005, p. 137.

- 1 2 Tallet 2012, p. 151.

- ↑ Gardiner, Peet & Černý 1955, Pl. IX num. 19.

- ↑ Strudwick 2005, p. 138.

- ↑ Tallet 2012, p. 20.

- 1 2 Tallet 2012, p. 150.

- ↑ Tallet 2010, p. 21.

- 1 2 3 Seal of office 68.115, BMFA 2015.

- 1 2 Harrell 2001, p. 395.

- ↑ "Nubia" & Catholic Encyclopedia 2016.

- ↑ Klemm & Klemm 2013, p. 604.

- ↑ Hayes 1978, p. 67.

- ↑ Wente 1990, pp. 20–21.

- ↑ Weigall 1907, p. 108, Pl. LVIII.

- ↑ Young 1972, p. 11.

- ↑ Sowada & Grave 2009, p. 146, footnote 89.

- ↑ Schulman 1979, p. 86.

- 1 2 Strudwick 2005, p. 371.

- ↑ Verner 2001b, p. 590.

- ↑ Kanawati & McFarlane 1993, pp. 26–27, pl. 2.

- ↑ Redford 1992, pp. 53–54.

- 1 2 3 Porter et al. 1981, p. 424.

- ↑ Grimal 1992, p. 118.

- ↑ Leclant 2015, p. 865.

- ↑ Batrawi 1947, p. 98.

- ↑ Baud & Dobrev 1995, p. 43, Note g.

- ↑ Baud & Dobrev 1995, p. 54.

- 1 2 Strudwick 2005, p. 77.

- ↑ Baud & Dobrev 1995, p. 41.

- ↑ Baud & Dobrev 1995, p. 25.

- ↑ Baud & Dobrev 1995, pp. 54–55.

- ↑ Marcolin 2006, p. 293, footnote (a).

Bibliography

- Altenmüller, Hartwig (2001). "Old Kingdom: Fifth Dynasty". In Redford, Donald B. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 597–601. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Andrassy, Petra (2008). Untersuchungen zum ägyptischen Staat des Alten Reiches und seinen Institutionen (PDF). Internet-Beiträge zur Ägyptologie und Sudanarchäologie, 11 (in German). Berlin; London: Golden House Publications. ISBN 978-1-90-613708-3.

- Baer, Klaus (1960). Rank and Title in the Old Kingdom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-22-603412-6.

- Baker, Darrell (2008). The Encyclopedia of the Pharaohs: Volume I – Predynastic to the Twentieth Dynasty 3300–1069 BC. Stacey International. ISBN 978-1-905299-37-9.

- Batrawi, Ahmed (1947). "The Pyramid Studies. Anatomical Reports". Annales du Service des antiquités de l'Egypte (ASAE) (Institut français d'archéologie orientale du Caire) 47: 97–111.

- Baud, Michel; Dobrev, Vassil (1995). "De nouvelles annales de l'Ancien Empire Egyptien. Une "Pierre de Palerme" pour la VIe dynastie" (PDF). Bulletin de l'Institut Francais d'Archeologie Orientale (BIFAO) (in French) 95: 23–92.

- Baud, Michel (1999a). Famille Royale et pouvoir sous l'Ancien Empire égyptien. Tome 1 (PDF). Bibliothèque d'étude 126/1 (in French). Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale. ISBN 978-2-7247-0250-7.

- Baud, Michel (1999b). Famille Royale et pouvoir sous l'Ancien Empire égyptien. Tome 2 (PDF). Bibliothèque d'étude 126/2 (in French). Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale. ISBN 978-2-7247-0250-7.

- Borchardt, Ludwig (1907). Das grabdenkmal des königs Ne-user-reʻ. Ausgrabungen der Deutschen orient-gesellschaft in Abusir 1902–1904 (in German). Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichs. OCLC 6724337.

- Brovarski, Edward (2001). Der Manuelian, Peter; Simpson, William Kelly, eds. The Senedjemib Complex, Part 1. The Mastabas of Senedjemib Inti (G 2370), Khnumenti (G 2374), and Senedjemib Mehi (G 2378). Giza Mastabas 7. Boston: Art of the Ancient World, Museum of Fine Arts. ISBN 978-0-87846-479-1.

- Clayton, Peter (1994). Chronicle of the Pharaohs. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05074-3.

- "Collection Online. Papyrus Abu Sir". British Museum. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- Dodson, Aidan; Hilton, Dyan (2004). The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd. ISBN 978-0-500-05128-3.

- Dorman, Peter (2015). "The 5th dynasty (c. 2465–c. 2325 bc)". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- Gardiner, Alan; Peet, Eric; Černý, Jaroslav (1955). The inscriptions of Sinai. London: Egypt Exploration Society. OCLC 699651.

- Gardiner, Alan (1959). The Royal Canon of Turin. Griffith Institute, Ashmolean Museum. OCLC 21484338.

- Goelet, Ogden (2015). "Abu Gurab". In Bard, Kathryn. An Introduction to the archaeology of ancient Egypt. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 85–87. ISBN 978-0-470-67336-2.

- Grimal, Nicolas (1992). A History of Ancient Egypt. Translated by Ian Shaw. Oxford: Blackwell publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-19396-8.

- Harrell, James (2001). "Diorite and related rocks". In Redford, Donald B. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 1. Oxford University Press. pp. 395–396. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Hawass, Zahi; Senussi, Ashraf (2008). Old Kingdom Pottery from Giza. American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-977-305-986-6.

- Hayes, William (1978). The Scepter of Egypt: A Background for the Study of the Egyptian Antiquities in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Vol. 1, From the Earliest Times to the End of the Middle Kingdom. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. OCLC 7427345.

- Horne, Charles Francis (1917). The Sacred Books and Early Literature of the East: with historical surveys of the chief writings of each nation. Vol. II: Egypt. New York: Parke, Austin, & Lipscomb. OCLC 557745.

- Hornung, Erik; Krauss, Rolf; Warburton, David, eds. (2012). Ancient Egyptian Chronology. Handbook of Oriental Studies. Leiden, Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-11385-5. ISSN 0169-9423.

- Kanawati, Naguib; McFarlane, Ann S. (1993). Deshasha: the tombs of Inti, Shedu and others. Reports (Australian Centre for Egyptology) 5. Sydney: The Australian Centre for Egyptology. ISBN 978-0-85-668617-7.

- Kanawati, Naguib (2003). Conspiracies in the Egyptian Palace: Unis to Pepy I. London; New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-20-316673-4.

- Klemm, Rosemarie; Klemm, Dietrich (2013). Gold and gold mining in ancient Egypt and Nubia : geoarchaeology of the ancient gold mining sites in the Egyptian and Sudanese eastern deserts. Natural science in archaeology. Berlin; New-York: Springer. ISBN 978-1-28-393479-4.

- Labrousse, Audran; Lauer, Jean-Philippe; Leclant, Jean (1977). Le temple haut du complexe funéraire du roi Ounas. Bibliothèque d'étude, tome 73. Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale du Caire. OCLC 5065554.

- Leclant, Jean (2015). "Saqqara, pyramids of the 5th and 6th Dynasties". In Bard, Kathryn. An Introduction to the archaeology of ancient Egypt. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 865–868. ISBN 978-0-470-67336-2.

- Leprohon, Ronald J. (2013). The great name: ancient Egyptian royal titulary. Writings from the ancient world, no. 33. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1-58983-736-2.

- Lepsius, Karl Richard (1846–1856). Denkmäler aus Ägypten und Äthiopien, Abteilung II Band III: Altes Reich (in German). Berlin. OCLC 60700892. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - Lloyd, Alan (2010). Lloyd, Alan, ed. A Companion to Ancient Egypt. Volume I. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-5598-4.

- Malek, Jaromir (2000). "The Old Kingdom (c.2160-2055 BC)". In Shaw, Ian. The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-815034-3.

- Marcolin, Michele (2006). "Iny, a much-traveled official of the Sixth Dynasty: unpublished reliefs in Japan". In Bárta, Miroslav; Coppens, Filip; Krejčí, Jaromír. Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2005, Proceedings of the Conference held in Prague (June 27–July 5, 2005). Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Oriental Institute. pp. 282–310. ISBN 978-8-07-308116-4.

- Mariette, Auguste (1864). "La table de Saqqarah". Revue Archeologique (in French) (Paris) 10: 168–186 & Pl. 17.

- Mariette, Auguste (1885). Maspero, Gaston, ed. Les mastabas de l'ancien empire : fragment du dernier ouvrage de Auguste Édouard Mariette (PDF). Paris: F. Vieweg. pp. 189–191. OCLC 722498663.

- Morales, Antonio J. (2006). "Traces of official and popular veneration to Nyuserra Iny at Abusir. Late Fifth Dynasty to the Middle Kingdom". In Bárta, Miroslav; Coppens, Filip; Krejčí, Jaromír. Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2005, Proceedings of the Conference held in Prague (June 27–July 5, 2005). Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Oriental Institute. pp. 311–341. ISBN 978-8-07-308116-4.

- Mumford, G. D. (2015). "Wadi Maghara". In Bard, Kathryn. An Introduction to the archaeology of ancient Egypt. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 1071–1075. ISBN 978-0-470-67336-2.

- "Nubia". Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- Posener-Kriéger, Paule; de Cenival, Jean Louis (1968). The Abu Sir Papyri. Hieratic papyri in the British Museum 5. London: Trustees of the British Museum. OCLC 5035958.

- Porter, Bertha; Moss, Rosalind L. B.; Burney, Ethel W.; Malek, Jaromír (1981). Topographical bibliography of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic texts, reliefs, and paintings. III Memphis; Pt. 2. Ṣaqqâra to Dahshûr (PDF). Oxford: Griffith Institute. ISBN 978-0-90-041624-8.

- Redford, Donald (1992). Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-03606-9.

- Rice, Michael (1999). Who is who in Ancient Egypt. Routledge London & New York. ISBN 978-0-203-44328-6.

- Schmitz, Bettina (1976). Untersuchungen zum Titel s3-njśwt "Königssohn". Habelts Dissertationsdrucke: Reihe Ägyptologie (in German) 2. Bonn: Habelt. ISBN 978-3-77-491370-7.

- Schott, E. (1977). "Die Biographie des Ka-em-tenenet". In Otto, Eberhard; Assmann, Jan; Feucht, Erika; Grieshammer, Reinhard. Fragen an die altägyptische Literatur : Studien zum Gedenken an Eberhard Otto (in German). Wiesbaden: Reichert. pp. 443–461. ISBN 978-3-88226-002-1.

- Schulman, Alan (1979). "Beyond the fringe. Sources for Old Kingdom foreign affairs". Journal of the Society for the Study of Egyptian Antiquities 9: 79–104. ISSN 0383-9753.

- "Seal of office". Collections: The Ancient World. Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- Sethe, Kurt Heinrich (1903). Urkunden des Alten Reichs (in German). wikipedia entry: Urkunden des Alten Reichs. Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichs. OCLC 846318602.

- Sicker, Martin (2000). The pre-Islamic Middle East. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-31-300083-6.

- Sowada, Karin N.; Grave, Peter (2009). Egypt in the Eastern Mediterranean during the Old Kingdom: an archaeological perspective. Orbis biblicus et orientalis, 237. Fribourg: Academic Press; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Stevenson Smith, William (1971). "The Old Kingdom in Egypt". In Edwards, I. E. S.; Gadd, C. J.; Hammond, N. G. L. The Cambridge Ancient History, Vol. 2, Part 2: Early History of the Middle East. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 145–207. ISBN 978-0-521-07791-0.

- Strudwick, Nigel (1985). The Administration of Egypt in the Old Kingdom: The Highest Titles and Their Holders (PDF). Studies in Egyptology. London; Boston: Kegan Paul International. ISBN 978-0-71-030107-9.

- Strudwick, Nigel C. (2005). Texts from the Pyramid Age. Writings from the Ancient World (book 16). Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1-58983-680-8.

- Tallet, Pierre (2010). "Prendre la mer à Ayn Soukhna au temps du roi Isesi" (PDF). Bulletin de la Société Française d'Egyptologie (BSFE) (in French). 177–178: 18–22.

- Tallet, Pierre (2012). "Ayn Sukhna and Wadi el-Jarf: Two newly discovered pharaonic harbours on the Suez Gulf" (PDF). British Museum Studies in Ancient Egypt and Sudan 18: 147–168.

- Thompson, Stephen (2015). "Textual sources, Old Kingdom". In Bard, Kathryn. An Introduction to the archaeology of ancient Egypt. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 976–978. ISBN 978-0-470-67336-2.

- "Tomb chapel of Raemkai, MMA online catalog". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- Tyldesley, Joyce (2005). À la découverte des pyramides d'Égypte. Champollion (in French). Translated by Nathalie Baum. Monaco: Éditions du Rocher. ISBN 978-2-26-805326-4.

- Verner, Miroslav (2001a). "Archaeological Remarks on the 4th and 5th Dynasty Chronology" (PDF). Archiv Orientální 69 (3): 363–418.

- Verner, Miroslav (2001b). "Old Kingdom: An Overview". In Redford, Donald B. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 585–591. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Verner, Miroslav (2002). The Pyramids: their Archaeology and History. London: Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-1-903809-45-7.

- von Beckerath, Jürgen (1999). Handbuch der ägyptischen Königsnamen (in German). Münchner ägyptologische Studien, Heft 49, Mainz : Philip von Zabern. ISBN 978-3-8053-2591-2.

- Waddell, William Gillan (1971). Manetho. Loeb classical library, 350. Cambridge, Massachusetts; London: Harvard University Press; W. Heinemann. OCLC 6246102.

- Weigall, Arthur (1907). A report on the antiquities of Lower Nubia (the first Cataract to the Sudan frontier) and their condition in 1906–7. Oxford: Oxford University Press. OCLC 6444528.

- Wente, Edward Frank (1990). Meltzer, Edmund S, ed. Letters from Ancient Egypt. Writings from the ancient world 1. Atlanta, Georgia: Scholars Press. ISBN 978-1-55-540473-4.

- Young, William J. (1972). "The Fabulous Gold of the Pactolus Valley" (PDF). Boston Museum Bulletin LXX.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Djedkare Isesi. |

| Preceded by Menkauhor Kaiu |

Pharaoh of Egypt Fifth Dynasty |

Succeeded by Unas |