Distance correlation

In statistics and in probability theory, distance correlation is a measure of statistical dependence between two random variables or two random vectors of arbitrary, not necessarily equal dimension. An important property is that this measure of dependence is zero if and only if the random variables are statistically independent. This measure is derived from a number of other quantities that are used in its specification, specifically: distance variance, distance standard deviation and distance covariance. These take the same roles as the ordinary moments with corresponding names in the specification of the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient.

These distance-based measures can be put into an indirect relationship to the ordinary moments by an alternative formulation (described below) using ideas related to Brownian motion, and this has led to the use of names such as Brownian covariance and Brownian distance covariance.

Background

The classical measure of dependence, the Pearson correlation coefficient,[1] is mainly sensitive to a linear relationship between two variables. Distance correlation was introduced in 2005 by Gabor J Szekely in several lectures to address this deficiency of Pearson’s correlation, namely that it can easily be zero for dependent variables. Correlation = 0 (uncorrelatedness) does not imply independence while distance correlation = 0 does imply independence. The first results on distance correlation were published in 2007 and 2009.[2][3] It was proved that distance covariance is the same as the Brownian covariance.[3] These measures are examples of energy distances.

Definitions

Distance covariance

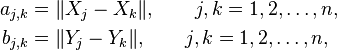

Let us start with the definition of the sample distance covariance. Let (Xk, Yk), k= 1, 2, ..., n be a statistical sample from a pair of real valued or vector valued random variables (X, Y). First, compute all pairwise distances

where || ⋅ || denotes Euclidean norm. That is, compute the n by n distance matrices (aj, k) and (bj, k). Then take all doubly centered distances

where  is the j-th row mean,

is the j-th row mean,  is the k-th column mean, and

is the k-th column mean, and  is the grand mean of the distance matrix of the X sample. The notation is similar for the b values. (In the matrices of centered distances (Aj, k) and (Bj,k) all rows and all columns sum to zero.) The squared sample distance covariance is simply the arithmetic average of the products Aj, k Bj, k:

is the grand mean of the distance matrix of the X sample. The notation is similar for the b values. (In the matrices of centered distances (Aj, k) and (Bj,k) all rows and all columns sum to zero.) The squared sample distance covariance is simply the arithmetic average of the products Aj, k Bj, k:

The statistic Tn = n dCov2n(X, Y) determines a consistent multivariate test of independence of random vectors in arbitrary dimensions. For an implementation see dcov.test function in the energy package for R.[4]

The population value of distance covariance can be defined along the same lines. Let X be a random variable that takes values in a p-dimensional Euclidean space with probability distribution μ and let Y be a random variable that takes values in a q-dimensional Euclidean space with probability distribution ν, and suppose that X and Y have finite expectations. Write

Finally, define the population value of squared distance covariance of X and Y as

One can show that this is equivalent to the following definition:

where E denotes expected value, and

and

and  are independent and identically distributed. Distance covariance can be expressed in terms of Pearson’s covariance,

cov, as follows:

are independent and identically distributed. Distance covariance can be expressed in terms of Pearson’s covariance,

cov, as follows:

This identity shows that the distance covariance is not the same as the covariance of distances, cov(||X-X' ||, ||Y-Y' ||). This can be zero even if X and Y are not independent.

Alternately, the squared distance covariance can be defined as the weighted L2 norm of the distance between the joint characteristic function of the random variables and the product of their marginal characteristic functions:[5]

where ϕX, Y(s, t), ϕX(s), and ϕY(t) are the characteristic functions of (X, Y), X, and Y, respectively, p, q denote the Euclidean dimension of X and Y, and thus of s and t, and cp, cq are constants. The weight function  is chosen to produce a scale equivariant and rotation invariant measure that doesn't go to zero for dependent variables.[5][6] One interpretation[7] of the characteristic function definition is that the variables eisX and eitY are cyclic representations of X and Y with different periods given by s and t, and the expression ϕX, Y(s, t) - ϕX(s) ϕY(t) in the numerator of the characteristic function definition of distance covariance is simply the classical covariance of eisX and eitY. The characteristic function definition clearly shows that

dCov2(X, Y) = 0 if and only if X and Y are independent.

is chosen to produce a scale equivariant and rotation invariant measure that doesn't go to zero for dependent variables.[5][6] One interpretation[7] of the characteristic function definition is that the variables eisX and eitY are cyclic representations of X and Y with different periods given by s and t, and the expression ϕX, Y(s, t) - ϕX(s) ϕY(t) in the numerator of the characteristic function definition of distance covariance is simply the classical covariance of eisX and eitY. The characteristic function definition clearly shows that

dCov2(X, Y) = 0 if and only if X and Y are independent.

Distance variance

The distance variance is a special case of distance covariance when the two variables are identical. The population value of distance variance is the square root of

where  denotes the expected value,

denotes the expected value,  is an independent and identically distributed copy of

is an independent and identically distributed copy of  and

and  is independent of

is independent of  and

and  and has the same distribution as

and has the same distribution as  and

and  .

.

The sample distance variance is the square root of

which is a relative of Corrado Gini’s mean difference introduced in 1912 (but Gini did not work with centered distances).

Distance standard deviation

The distance standard deviation is the square root of the distance variance.

Distance correlation

The distance correlation [2][3] of two random variables is obtained by dividing their distance covariance by the product of their distance standard deviations. The distance correlation is

and the sample distance correlation is defined by substituting the sample distance covariance and distance variances for the population coefficients above.

For easy computation of sample distance correlation see the dcor function in the energy package for R.[4]

Properties

Distance correlation

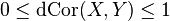

(i)  and

and  .

.

(ii)  if and only if

if and only if  and

and  are independent.

are independent.

(iii)  implies that dimensions of the linear subspaces spanned by

implies that dimensions of the linear subspaces spanned by  and

and  samples respectively are almost surely equal and if we assume that these subspaces are equal, then in this subspace

samples respectively are almost surely equal and if we assume that these subspaces are equal, then in this subspace  for some vector

for some vector  , scalar

, scalar  , and orthonormal matrix

, and orthonormal matrix  .

.

Distance covariance

(i)  and

and  .

.

(ii)  for all constant vectors

for all constant vectors  , scalars

, scalars  , and orthonormal matrices

, and orthonormal matrices  .

.

(iii) If the random vectors  and

and  are independent then

are independent then

Equality holds if and only if  and

and  are both constants, or

are both constants, or  and

and  are both constants, or

are both constants, or  are mutually independent.

are mutually independent.

(iv)  if and only if

if and only if  and

and  are independent.

are independent.

This last property is the most important effect of working with centered distances.

The statistic  is a biased estimator of

is a biased estimator of  . Under independence of X and Y [8]

. Under independence of X and Y [8]

An unbiased estimator of  is given by Székely and Rizzo.[9]

is given by Székely and Rizzo.[9]

Distance variance

(i)  if and only if

if and only if ![X = \operatorname{E}[X]](../I/m/6bd97a8222f45fc2b2aea5859ae55d8e.png) almost surely.

almost surely.

(ii)  if and only if every sample observation is identical.

if and only if every sample observation is identical.

(iii)  for all constant vectors

for all constant vectors  , scalars

, scalars  , and orthonormal matrices

, and orthonormal matrices  .

.

(iv) If  and

and  are independent then

are independent then  .

.

Equality holds in (iv) if and only if one of the random variables  or

or  is a constant.

is a constant.

Generalization

Distance covariance can be generalized to include powers of Euclidean distance. Define

Then for every  ,

,  and

and  are independent if and only if

are independent if and only if  . It is important to note that this characterization does not hold for exponent

. It is important to note that this characterization does not hold for exponent  ; in this case for bivariate

; in this case for bivariate  ,

,  is a deterministic function of the Pearson correlation.[2] If

is a deterministic function of the Pearson correlation.[2] If  and

and  are

are  powers of the corresponding distances,

powers of the corresponding distances,  , then

, then  sample distance covariance can be defined as the nonnegative number for which

sample distance covariance can be defined as the nonnegative number for which

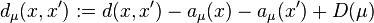

One can extend  to metric-space-valued random variables

to metric-space-valued random variables  and

and  : If

: If  has law

has law  in a metric space with metric

in a metric space with metric  , then define

, then define ![a_\mu(x):= \operatorname{E}[d(X, x)]](../I/m/047a394b3a6b8964491725ede14f189c.png) ,

, ![D(\mu) := \operatorname{E}[a_\mu(X)]](../I/m/cb5fa2640274b14c17d8bbbdd978f33f.png) , and (provided

, and (provided  is finite, i.e.,

is finite, i.e.,  has finite first moment),

has finite first moment),  . Then if

. Then if  has law

has law  (in a possibly different metric space with finite first moment), define

(in a possibly different metric space with finite first moment), define

This is non-negative for all such  iff both metric spaces have negative type.[10]

Here, a metric space

iff both metric spaces have negative type.[10]

Here, a metric space  has negative type

if

has negative type

if  is isometric to a subset of a Hilbert space.[11]

If both metric spaces have strong negative type, then

is isometric to a subset of a Hilbert space.[11]

If both metric spaces have strong negative type, then  iff

iff  are independent.[10]

are independent.[10]

Alternative definition of distance covariance

The original distance covariance has been defined as the square root of  , rather than the squared coefficient itself.

, rather than the squared coefficient itself.  has the property that it is the energy distance between the joint distribution of

has the property that it is the energy distance between the joint distribution of  and the product of its marginals. Under this definition, however, the distance variance, rather than the distance standard deviation, is measured in the same units as the

and the product of its marginals. Under this definition, however, the distance variance, rather than the distance standard deviation, is measured in the same units as the  distances.

distances.

Alternately, one could define distance covariance to be the square of the energy distance:

In this case, the distance standard deviation of

In this case, the distance standard deviation of  is measured in the same units as

is measured in the same units as  distance, and there exists an unbiased estimator for the population distance covariance.[9]

distance, and there exists an unbiased estimator for the population distance covariance.[9]

Under these alternate definitions, the distance correlation is also defined as the square  , rather than the square root.

, rather than the square root.

Alternative formulation: Brownian covariance

Brownian covariance is motivated by generalization of the notion of covariance to stochastic processes. The square of the covariance of random variables X and Y can be written in the following form:

where E denotes the expected value and the prime denotes independent and identically distributed copies. We need the following generalization of this formula. If U(s), V(t) are arbitrary random processes defined for all real s and t then define the U-centered version of X by

whenever the subtracted conditional expected value exists and denote by YV the V-centered version of Y.[3][12][13] The (U,V) covariance of (X,Y) is defined as the nonnegative number whose square is

whenever the right-hand side is nonnegative and finite. The most important example is when U and V are two-sided independent Brownian motions /Wiener processes with expectation zero and covariance |s| + |t| - |s-t| = 2 min(s,t). (This is twice the covariance of the standard Wiener process; here the factor 2 simplifies the computations.) In this case the (U,V) covariance is called Brownian covariance and is denoted by

There is a surprising coincidence: The Brownian covariance is the same as the distance covariance:

and thus Brownian correlation is the same as distance correlation.

On the other hand, if we replace the Brownian motion with the deterministic identity function id then Covid(X,Y) is simply the absolute value of the classical Pearson covariance,

See also

- RV coefficient

- For a related third-order statistic, see Distance skewness.

Notes

- ↑ Pearson (1895)

- 1 2 3 Székely, Rizzo and Bakirov (2007)

- 1 2 3 4 Székely & Rizzo (2009)

- 1 2 energy package for R

- 1 2 Székely & Rizzo (2009) Theorem 7, (3.7), p. 1249.

- ↑ Székely, G. J. and Rizzo, M. L. (2012). "On the uniqueness of distance covariance". Statistics & Probability Letters 82 (12): 2278–2282. doi:10.1016/j.spl.2012.08.007.

- ↑ "How distance correlation works". Retrieved 2012-12-13.

- ↑ Székely and Rizzo (2009), Rejoinder

- 1 2 Székely & Rizzo (2014)

- 1 2 Lyons, R. (2011) "Distance covariance in metric spaces". arXiv:1106.5758

- ↑ Klebanov, L. B. (2005) N-distances and their Applications, Karolinum Press, Charles University, Prague.

- ↑ Bickel & Xu (2009)

- ↑ Kosorok (2009)

References

- Bickel, P.J. and Xu, Y. (2009) "Discussion of: Brownian distance covariance", Annals of Applied Statistics, 3 (4), 1266–1269. doi:10.1214/09-AOAS312A Free access to article

- Gini, C. (1912). Variabilità e Mutabilità. Bologna: Tipografia di Paolo Cuppini.

- Pearson, K. (1895). "Note on regression and inheritance in the case of two parents", Proceedings of the Royal Society, 58, 240–242

- Pearson, K. (1920). "Notes on the history of correlation", Biometrika, 13, 25–45.

- Székely, G. J. Rizzo, M. L. and Bakirov, N. K. (2007). "Measuring and testing independence by correlation of distances", The Annals of Statistics, 35/6, 2769–2794. doi: 10.1214/009053607000000505 Reprint

- Székely, G. J. and Rizzo, M. L. (2009). "Brownian distance covariance", Annals of Applied Statistics, 3/4, 1233–1303. doi: 10.1214/09-AOAS312 Reprint

- Kosorok, M. R. (2009) "Discussion of: Brownian Distance Covariance", Annals of Applied Statistics, 3/4, 1270–1278. doi:10.1214/09-AOAS312B Free access to article

- Székely, G.J. and Rizzo, M.L. (2014) Partial distance correlation with methods for dissimilarities, The Annals of Statistics, 42/6, 2382-2412.

![a_\mu(x):= \operatorname{E}[\|X-x\|], \quad D(\mu) := \operatorname{E}[a_\mu(X)], \quad d_\mu(x, x') := \|x-x'\|-a_\mu(x)-a_\mu(x')+D(\mu).](../I/m/6e7cb64f2f1c47e2b811aeb5d925b985.png)

![\operatorname{dCov}^2(X, Y) := \operatorname{E}\big[d_\mu(X,X')d_\nu(Y,Y')\big].](../I/m/7a13258a0f3f4f463c5f049f7328e5c7.png)

![\begin{align}

\operatorname{dCov}^2(X,Y) & := \operatorname{E}[\|X-X'\|\,\|Y-Y'\|] + \operatorname{E}[\|X-X'\|]\,\operatorname{E}[\|Y-Y'\|] \\

&\qquad - \operatorname{E}[\|X-X'\|\,\|Y-Y''\|] - \operatorname{E}[\|X-X''\|\,\|Y-Y'\|]

\\

& = \operatorname{E}[\|X-X'\|\,\|Y-Y'\|] + \operatorname{E}[\|X-X'\|]\,\operatorname{E}[\|Y-Y'\|] \\

&\qquad - 2\operatorname{E}[\|X-X'\|\,\|Y-Y''\|],

\end{align}](../I/m/536fce7f41fd77d9998ff0a558fc3655.png)

![\operatorname{dVar}^2(X) := \operatorname{E}[\|X-X'\|^2] + \operatorname{E}^2[\|X-X'\|] - 2\operatorname{E}[\|X-X'\|\,\|X-X''\|],](../I/m/5aac4f5b80f3c67b72976a2dd810c79d.png)

![\operatorname{E}[\operatorname{dCov}^2_n(X,Y)] = \frac{n-1}{n^2} \left\{(n-2) \operatorname{dCov}^2(X,Y)+ \operatorname{E}[\|X-X'\|]\,\operatorname{E}[\|Y-Y'\|] \right\} = \frac{n-1}{n^2}\operatorname {E}[\|X-X'\|]\,\operatorname{E}[\|Y-Y'\|].](../I/m/19e11c50374b709718a5c6511f5ad801.png)

![\begin{align}

\operatorname{dCov}^2(X, Y; \alpha) &:= \operatorname{E}[\|X-X'\|^\alpha\,\|Y-Y'\|^\alpha] + \operatorname{E}[\|X-X'\|^\alpha]\,\operatorname{E}[\|Y-Y'\|^\alpha]\\

&\qquad - 2\operatorname{E}[\|X-X'\|^\alpha\,\|Y-Y''\|^\alpha].

\end{align}](../I/m/126049c50558c7e52ff10775baac41f1.png)

![\operatorname{cov}(X,Y)^2 = \operatorname{E}\left[

\big(X - \operatorname{E}(X)\big)

\big(X^\mathrm{'} - \operatorname{E}(X^\mathrm{'})\big)

\big(Y - \operatorname{E}(Y)\big)

\big(Y^\mathrm{'} - \operatorname{E}(Y^\mathrm{'})\big)

\right]](../I/m/6388e75e4f42586b1d36da2cd3a37cc8.png)

![X_U := U(X) - \operatorname{E}_X\left[ U(X) \mid \left \{ U(t) \right \} \right]](../I/m/fc4b747f0c98aeb05fdc0581f8248624.png)

![\operatorname{cov}_{U,V}^2(X,Y) := \operatorname{E}\left[X_U X_U^\mathrm{'} Y_V Y_V^\mathrm{'}\right]](../I/m/3f2fa14fcdbfe145baea3e1b9e8b909b.png)