Distance measures (cosmology)

| Part of a series on | |||

| Physical cosmology | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

|

Early universe

|

|||

|

Components · Structure |

|||

| |||

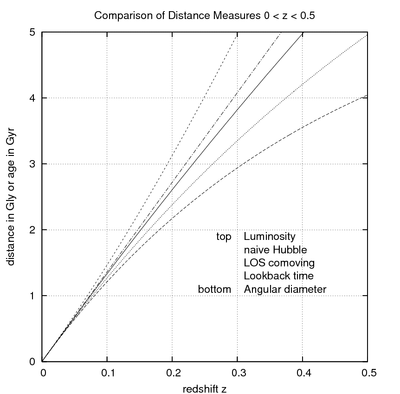

Distance measures are used in physical cosmology to give a natural notion of the distance between two objects or events in the universe. They are often used to tie some observable quantity (such as the luminosity of a distant quasar, the redshift of a distant galaxy, or the angular size of the acoustic peaks in the CMB power spectrum) to another quantity that is not directly observable, but is more convenient for calculations (such as the comoving coordinates of the quasar, galaxy, etc.). The distance measures discussed here all reduce to the common notion of Euclidean distance at low redshift.

In accord with our present understanding of cosmology, these measures are calculated within the context of general relativity, where the Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker solution is used to describe the universe.

Overview

There are a few different definitions of "distance" in cosmology which all coincide for sufficiently small redshifts. The expressions for these distances are most practical when written as functions of redshift  , since redshift is always the observable. They can easily be written as functions of scale factor

, since redshift is always the observable. They can easily be written as functions of scale factor  , cosmic

, cosmic  or conformal time

or conformal time  as well by performing a simple transformation of variables. By defining the dimensionless Hubble parameter

as well by performing a simple transformation of variables. By defining the dimensionless Hubble parameter

and the Hubble distance  , the relation between the different distances becomes apparent. Here,

, the relation between the different distances becomes apparent. Here,  is the total matter density,

is the total matter density,  is the dark energy density,

is the dark energy density,  represents the curvature,

represents the curvature,  is the Hubble parameter today and

is the Hubble parameter today and  is the speed of light. The Hubble parameter at a given redshift is then

is the speed of light. The Hubble parameter at a given redshift is then  . The following measures for distances from the observer to an object at redshift

. The following measures for distances from the observer to an object at redshift  along the line of sight are commonly used in cosmology:[1]

along the line of sight are commonly used in cosmology:[1]

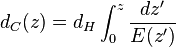

Comoving distance:

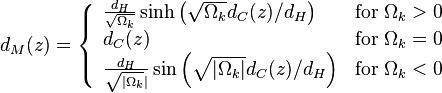

Transverse comoving distance:

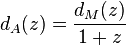

Angular diameter distance:

Luminosity distance:

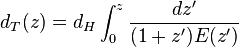

Light-travel distance:

Note that the comoving distance is recovered from the transverse comoving distance by taking the limit  , such that the two distance measures are equivalent in a flat universe.

, such that the two distance measures are equivalent in a flat universe.

Age of the universe is  , and the time elapsed since redshift

, and the time elapsed since redshift  until now is

until now is

,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  chosen so that the sum of Omega parameters is 1.

chosen so that the sum of Omega parameters is 1.

,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  chosen so that the sum of Omega parameters is one.

chosen so that the sum of Omega parameters is one.Alternative terminology

Peebles (1993) calls the transverse comoving distance the "angular size distance", which is not to be mistaken for the angular diameter distance.[2] Even though it is not a matter of nomenclature, the comoving distance is equivalent to the proper motion distance, which is defined as the ratio of the transverse velocity and its proper motion in radians per time. Occasionally, the symbols  or

or  are used to denote both the comoving and the angular diameter distance. Sometimes, the light-travel distance is also called the "lookback distance".

are used to denote both the comoving and the angular diameter distance. Sometimes, the light-travel distance is also called the "lookback distance".

Details

Comoving distance

The comoving distance between fundamental observers, i.e. observers that are comoving with the Hubble flow, does not change with time, as it accounts for the expansion of the universe. It is obtained by integrating up the proper distances of nearby fundamental observers along the line of sight (LOS), where the proper distance is what a measurement at constant cosmic time would yield.

Transverse comoving distance

Two comoving objects at constant redshift  that are separated by an angle

that are separated by an angle  on the sky are said to have the distance

on the sky are said to have the distance  , where the transverse comoving distance

, where the transverse comoving distance  is defined appropriately.

is defined appropriately.

Angular diameter distance

An object of size  at redshift

at redshift  that appears to have angular size

that appears to have angular size  has the angular diameter distance of

has the angular diameter distance of  . This is commonly used to observe so called standard rulers, for example in the context of baryon acoustic oscillations.

. This is commonly used to observe so called standard rulers, for example in the context of baryon acoustic oscillations.

Luminosity distance

If the intrinsic luminosity  of a distant object is known, we can calculate its luminosity distance by measuring the flux

of a distant object is known, we can calculate its luminosity distance by measuring the flux  and determine

and determine  , which turns out to be equivalent to the expression above for

, which turns out to be equivalent to the expression above for  . This quantity is important for measurements of standard candles like type Ia supernovae, which were first used to discover the acceleration of the expansion of the universe.

. This quantity is important for measurements of standard candles like type Ia supernovae, which were first used to discover the acceleration of the expansion of the universe.

Light-travel distance

This distance is the time (in years) that it took light to reach the observer from the object multiplied by the speed of light. For instance, the radius of the observable universe in this distance measure becomes the age of the universe multiplied by the speed of light (1 light year/year) i.e. 13.8 billion light years. Also see misconceptions about the size of the visible universe.

Etherington's distance duality

The Etherington's distance-duality equation [3] is the relationship between the luminosity distance of standard candles and the angular-diameter distance. It is expressed as follows:

See also

- Big Bang

- Comoving distance

- Friedmann equations

- Physical cosmology

- Cosmic distance ladder

- Friedmann-Lemaître-Robertson-Walker metric

References

- ↑ David W. Hogg (2000). "Distance measures in cosmology". arXiv:astro-ph/9905116v4.

- ↑ Peebles, P. J. E. (1993). Principles of Physical Cosmology. Princeton University Press. pp. 310–320. Bibcode:1993ppc..book.....P. ISBN 978-0-691-01933-8.

- ↑ I.M.H. Etherington, “LX. On the Definition of Distance in General Relativity”, Philosophical Magazine, Vol. 15, S. 7 (1933), pp. 761-773.

- Scott Dodelson, Modern Cosmology. Academic Press (2003).

External links

- 'The Distance Scale of the Universe' compares different cosmological distance measures.

- 'Distance measures in cosmology' explains in detail how to calculate the different distance measures as a function of world model and redshift.

- iCosmos: Cosmology Calculator (With Graph Generation ) calculates the different distance measures as a function of cosmological model and redshift, and generates plots for the model from redshift 0 to 20.