Disjunction and existence properties

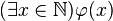

In mathematical logic, the disjunction and existence properties are the "hallmarks" of constructive theories such as Heyting arithmetic and constructive set theories (Rathjen 2005). The disjunction property is satisfied by a theory if, whenever a sentence A ∨ B is a theorem, then either A is a theorem, or B is a theorem. The existence property or witness property is satisfied by a theory if, whenever a sentence (∃x)A(x) is a theorem, where A(x) has no other free variables, then there is some term t such that the theory proves A(t).

Related properties

Rathjen (2005) lists five properties that a theory may possess. These include the disjunction property (DP), the existence property (EP), and three additional properties:

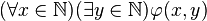

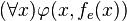

- The numerical existence property (NEP) states that if the theory proves

, where φ has no other free variables, then the theory proves

, where φ has no other free variables, then the theory proves  for some

for some  . Here

. Here  is a term in

is a term in  representing the number n.

representing the number n. - Church's rule (CR) states that if the theory proves

then there is a natural number e such that, letting

then there is a natural number e such that, letting  be the computable function with index e, the theory proves

be the computable function with index e, the theory proves  .

. - A variant of Church's rule, CR1, states that if the theory proves

then there is a natural number e such that the theory proves

then there is a natural number e such that the theory proves  is total and proves

is total and proves  .

.

These properties can only be directly expressed for theories that have the ability to quantify over natural numbers and, for CR1, quantify over functions from  to

to  . In practice, one may say that a theory has one of these properties if a definitional extension of the theory has the property stated above (Rathjen 2005).

. In practice, one may say that a theory has one of these properties if a definitional extension of the theory has the property stated above (Rathjen 2005).

Background and history

Kurt Gödel (1932) proved that intuitionistic propositional logic (with no additional axioms) has the disjunction property; this result was extended to intuitionistic predicate logic by Gerhard Gentzen (1934, 1935). Stephen Cole Kleene (1945) proved that Heyting arithmetic has the disjunction property and the existence property. Kleene's method introduced the technique of realizability, which is now one of the main methods in the study of constructive theories (Kohlenbach 2008; Troelstra 1973).

While the earliest results were for constructive theories of arithmetic, many results are also known for constructive set theories (Rathjen 2005). John Myhill (1973) showed that IZF with the axiom of Replacement eliminated in favor of the axiom of Collection has the disjunction property, the numerical existence property, and the existence property. Michael Rathjen (2005) proved that CZF has the disjunction property and the numerical existence property.

Most classical theories, such as Peano arithmetic and ZFC do not have the existence or disjunction property. Some classical theories, such as ZFC plus the axiom of constructibility, do have a weaker form of the existence property (Rathjen 2005).

In topoi

Freyd and Scedrov (1990) observed that the disjunction property holds in free Heyting algebras and free topoi. In categorical terms, in the free topos, that corresponds to the fact that the terminal object,  , is not the join of two proper subobjects. Together with the existence property it translates to the assertion that

, is not the join of two proper subobjects. Together with the existence property it translates to the assertion that  is an indecomposable projective object – the functor it represents (the global-section functor) preserves epimorphisms and coproducts.

is an indecomposable projective object – the functor it represents (the global-section functor) preserves epimorphisms and coproducts.

Relationships

There are several relationship between the five properties discussed above.

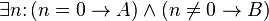

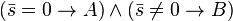

The numerical existence property implies the disjunction property. The proof uses the fact that a disjunction can be rewritten as an existential formula quantifying over natural numbers:

-

![A \vee B \equiv (\exists n) [ (n=0 \to A) \wedge (n \neq 0 \to B)]](../I/m/e7e5cc72bf92e555ce7857e848095b79.png) .

.

Therefore, if  is a theorem of

is a theorem of  , so is

, so is  . Thus, assuming the numerical existence property, there exists some

. Thus, assuming the numerical existence property, there exists some  such that

such that  is a theorem. Since

is a theorem. Since  is a numeral, one may concretely check the value of

is a numeral, one may concretely check the value of  : if

: if  then

then  is a theorem and if

is a theorem and if  then

then  is a theorem.

is a theorem.

Harvey Friedman (1974) proved that in any recursively enumerable extension of intuitionistic arithmetic, the disjunction property implies the numerical existence property. The proof uses self-referential sentences in way similar to the proof of Gödel's incompleteness theorems. The key step is to find a bound on the existential quantifier in a formula (∃x)A(x), producing a because bounded existential formula (∃x<n)A(x). The bounded formula may then be written as a finite disjunction A(1)∨A(2)∨...∨A(n). Finally, disjunction elimination may be used to show that one of the disjuncts is provable.

References

- Petre J. Freyd and Andre Scedrov, 1990, Categories, Allegories. North-Holland.

- Harvey Friedman, 1975, The disjunction property implies the numerical existence property, State University of New York at Buffalo.

- Gerhard Gentzen, 1934, "Untersuchungen über das logische Schließen. I", Mathematische Zeitschrift v. 39 n. 2, pp. 176–210.

- Gerhard Gentzen, 1935, "Untersuchungen über das logische Schließen. II", Mathematische Zeitschrift v. 39 n. 3, pp. 405–431.

- Kurt Gödel, 1932, "Zum intuitionistischen Aussagenkalkül", Anzeiger der Akademie der Wissenschaftischen in Wien, v. 69, pp. 65–66.

- Stephen Cole Kleene, 1945, “On the interpretation of intuitionistic number theory,” Journal of Symbolic Logic, v. 10, pp. 109–124.

- Ulrich Kohlenbach, 2008, Applied proof theory, Springer.

- John Myhill, 1973, "Some properties of Intuitionistic Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory", in A. Mathias and H. Rogers, Cambridge Summer School in Mathematical Logic, Lectures Notes in Mathematics v. 337, pp. 206–231, Springer.

- Michael Rathjen, 2005, "The Disjunction and Related Properties for Constructive Zermelo-Fraenkel Set Theory", Journal of Symbolic Logic, v. 70 n. 4, pp. 1233–1254.

- Anne S. Troelstra, ed. (1973), Metamathematical investigation of intuitionistic arithmetic and analysis, Springer.

External links

- Intuitionistic Logic by Joan Moschovakis, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy