Pigeonhole principle

In mathematics, the pigeonhole principle states that if n items are put into m containers, with n > m, then at least one container must contain more than one item.[1] This theorem is exemplified in real-life by truisms like "there must be at least two left gloves or two right gloves in a group of three gloves". It is an example of a counting argument, and despite seeming intuitive it can be used to demonstrate possibly unexpected results; for example, that two people in London have the same number of hairs on their heads (see below).

The first formalization of the idea is believed to have been made by Peter Gustav Lejeune Dirichlet in 1834 under the name Schubfachprinzip ("drawer principle" or "shelf principle"). For this reason it is also commonly called Dirichlet's box principle, Dirichlet's drawer principle or simply "Dirichlet's principle"[2] — a name that could also refer to the minimum principle for harmonic functions. The original "drawer" name is still in use in French ("principe des tiroirs"), Polish ("zasada szufladkowa"), Bulgarian ("принцип на чекмеджетата"), Turkish ("çekmece ilkesi"), Hungarian ("skatulyaelv"), Italian ("principio dei cassetti"), German ("Schubfachprinzip"), Dutch ("ladenprincipe "), Danish ("Skuffeprincippet"), and Chinese ("抽屉原理").

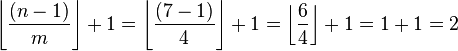

The principle has several generalizations and can be stated in various ways. In a more quantified version: for natural numbers k and m, if n = km + 1 objects are distributed among m sets, then the pigeonhole principle asserts that at least one of the sets will contain at least k + 1 objects.[3] For arbitrary n and m this generalizes to k + 1 = ⌊(n - 1)/m⌋ + 1, where ⌊...⌋ is the floor function.

Though the most straightforward application is to finite sets (such as pigeons and boxes), it is also used with infinite sets that cannot be put into one-to-one correspondence. To do so requires the formal statement of the pigeonhole principle, which is "there does not exist an injective function whose codomain is smaller than its domain". Advanced mathematical proofs like Siegel's lemma build upon this more general concept.

Examples

Sock-picking

Assume you have a mixture of black socks and blue socks, what is the minimum number of socks needed before a pair of the same color can be guaranteed? Using the pigeonhole principle, to have at least one pair of the same color (m = 2 holes, one per color) using one pigeonhole per color, you need only three socks (n = 3 items).

Hand-shaking

If there are n people who can shake hands with one another (where n > 1), the pigeonhole principle shows that there is always a pair of people who will shake hands with the same number of people. As the 'holes', or m, correspond to number of hands shaken, and each person can shake hands with anybody from 0 to n − 1 other people, this creates n − 1 possible holes. This is because either the '0' or the 'n − 1' hole must be empty (if one person shakes hands with everybody, it's not possible to have another person who shakes hands with nobody; likewise, if one person shakes hands with no one there cannot be a person who shakes hands with everybody). This leaves n people to be placed in at most n − 1 non-empty holes, guaranteeing duplication.

Hair-counting

We can demonstrate there must be at least two people in London with the same number of hairs on their heads as follows.[4] Since a typical human head has an average of around 150,000 hairs, it is reasonable to assume (as an upper bound) that no one has more than 1,000,000 hairs on their head (m = 1 million holes). There are more than 1,000,000 people in London (n is bigger than 1 million items). Assigning a pigeonhole to each number of hairs on a person's head, and assign people to pigeonholes according to the number of hairs on their head, there must be at least two people assigned to the same pigeonhole by the 1,000,001st assignment (because they have the same number of hairs on their heads) (or, n > m). For the average case (m = 150,000) with the constraint: fewest overlaps, there will be at most one person assigned to every pigeonhole and the 150,001st person assigned to the same pigeonhole as someone else. In the absence of this constraint, there may be empty pigeonholes because the "collision" happens before we get to the 150,001st person. The principle just proves the existence of an overlap; it says nothing of the number of overlaps (which falls under the subject of Probability Distribution).

The birthday problem

The birthday problem asks, for a set of n randomly chosen people, what is the probability that some pair of them will have the same birthday? By the pigeonhole principle, if there are 367 people in the room, we know that there is at least one pair who share the same birthday, as there are only 366 possible birthdays to choose from (including February 29, if present). The birthday "paradox" refers to the result that even if the group is as small as 23 individuals, there will still be a pair of people with the same birthday with a 50% probability. While at first glance this may seem surprising, it intuitively makes sense when considering that a comparison will actually be made between every possible pair of people rather than fixing one individual and comparing them solely to the rest of the group.

Softball team

Imagine seven people who want to play softball (n = 7 items), with a limitation of only four softball teams (m = 4 holes) to choose from. The pigeonhole principle tells us that they cannot all play for different teams. At least 2 must play on the same team:

Subset sum

Any subset of size six from the set S = {1,2,3,...,9} must contain two elements whose sum is 10. The pigeonholes will be labelled by the two element subsets {1,9}, {2,8}, {3,7}, {4,6} and the singleton {5}, five pigeonholes in all. When the six "pigeons" (elements of the size six subset) are placed into these pigeonholes, each pigeon going into the pigeonhole that has it contained in its label, at least one of the pigeonholes labelled with a two element subset will have two pigeons in it.[5]

Uses and applications

The pigeonhole principle arises in computer science. For example, collisions are inevitable in a hash table because the number of possible keys exceeds the number of indices in the array. A hashing algorithm, no matter how clever, cannot avoid these collisions.

The principle can be used to prove that any lossless compression algorithm, provided it makes some inputs smaller (as the name compression suggests), will also make some other inputs larger. Otherwise, the set of all input sequences up to a given length L could be mapped to the (much) smaller set of all sequences of length less than L without collisions (because the compression is lossless), a possibility which the pigeonhole principle excludes.

A notable problem in mathematical analysis is, for a fixed irrational number a, to show that the set {[na]: n is an integer} of fractional parts is dense in [0, 1]. One finds that it is not easy to explicitly find integers n, m such that |na − ma| < e, where e > 0 is a small positive number and a is some arbitrary irrational number. But if one takes M such that 1/M < e, by the pigeonhole principle there must be n1, n2 ∈ {1, 2, ..., M + 1} such that n1a and n2a are in the same integer subdivision of size 1/M (there are only M such subdivisions between consecutive integers). In particular, we can find n1, n2 such that n1a is in (p + k/M, p + (k + 1)/M), and n2a is in (q + k/M, q + (k + 1)/M), for some p, q integers and k in {0, 1, ..., M − 1}. We can then easily verify that (n2 − n1)a is in (q − p − 1/M, q − p + 1/M). This implies that [na] < 1/M < e, where n = n2 − n1 or n = n1 − n2. This shows that 0 is a limit point of {[na]}. We can then use this fact to prove the case for p in (0, 1]: find n such that [na] < 1/M < e; then if p ∈ (0, 1/M], we are done. Otherwise p ∈ (j/M, (j + 1)/M], and by setting k = sup{r ∈ N : r[na] < j/M}, one obtains |[(k + 1)na] − p| < 1/M < e.

Alternate formulations

The following are alternate formulations of the pigeonhole principle.

- If n objects are distributed over m places, and if n > m, then some place receives at least two objects.[1]

- (equivalent formulation of 1) If n objects are distributed over n places in such a way that no place receives more than one object, then each place receives exactly one object.[1]

- If n objects are distributed over m places, and if n < m, then some place receives no object.

- (equivalent formulation of 3) If n objects are distributed over n places in such a way that no place receives no object, then each place receives exactly one object.[6]

Strong form

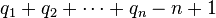

Let q1, q2, ..., qn be positive integers. If

objects are distributed into n boxes, then either the first box contains at least q1 objects, or the second box contains at least q2 objects, ..., or the nth box contains at least qn objects.[7]

The simple form is obtained from this by taking q1 = q2 = ... = qn = 2, which gives n + 1 objects. Taking q1 = q2 = ... = qn = r gives the more quantified version of the principle, namely:

Let n and r be positive integers. If n(r - 1) + 1 objects are distributed into n boxes, then at least one of the boxes contains r or more of the objects.[8]

This can also be stated as, if k discrete objects are to be allocated to n containers, then at least one container must hold at least  objects, where

objects, where  is the ceiling function, denoting the smallest integer larger than or equal to x.

Similarly, at least one container must hold no more than

is the ceiling function, denoting the smallest integer larger than or equal to x.

Similarly, at least one container must hold no more than  objects, where

objects, where  is the floor function, denoting the largest integer smaller than or equal to x.

is the floor function, denoting the largest integer smaller than or equal to x.

Generalizations of the pigeonhole principle

A probabilistic generalization of the pigeonhole principle states that if n pigeons are randomly put into m pigeonholes with uniform probability 1/m, then at least one pigeonhole will hold more than one pigeon with probability

where (m)n is the falling factorial m(m − 1)(m − 2)...(m − n + 1). For n = 0 and for n = 1 (and m > 0), that probability is zero; in other words, if there is just one pigeon, there cannot be a conflict. For n > m (more pigeons than pigeonholes) it is one, in which case it coincides with the ordinary pigeonhole principle. But even if the number of pigeons does not exceed the number of pigeonholes (n ≤ m), due to the random nature of the assignment of pigeons to pigeonholes there is often a substantial chance that clashes will occur. For example, if 2 pigeons are randomly assigned to 4 pigeonholes, there is a 25% chance that at least one pigeonhole will hold more than one pigeon; for 5 pigeons and 10 holes, that probability is 69.76%; and for 10 pigeons and 20 holes it is about 93.45%. If the number of holes stays fixed, there is always a greater probability of a pair when you add more pigeons. This problem is treated at much greater length in the birthday paradox.

A further probabilistic generalization is that when a real-valued random variable X has a finite mean E(X), then the probability is nonzero that X is greater than or equal to E(X), and similarly the probability is nonzero that X is less than or equal to E(X). To see that this implies the standard pigeonhole principle, take any fixed arrangement of n pigeons into m holes and let X be the number of pigeons in a hole chosen uniformly at random. The mean of X is n/m, so if there are more pigeons than holes the mean is greater than one. Therefore, X is sometimes at least 2.

Infinite sets

The pigeonhole principle can be extended to infinite sets by phrasing it in terms of cardinal numbers: if the cardinality of set A is greater than the cardinality of set B, then there is no injection from A to B. However, in this form the principle is tautological, since the meaning of the statement that the cardinality of set A is greater than the cardinality of set B is exactly that there is no injective map from A to B. However, adding at least one element to a finite set is sufficient to ensure that the cardinality increases.

Another way to phrase the pigeonhole principle for finite sets is similar to the principle that finite sets are Dedekind finite: Let A and B be finite sets. If there is a surjection from A to B that is not injective, then no surjection from A to B is injective. In fact no function of any kind from A to B is injective. This is not true for infinite sets: Consider the function on the natural numbers that sends 1 and 2 to 1, 3 and 4 to 2, 5 and 6 to 3, and so on.

There is a similar principle for infinite sets: If uncountably many pigeons are stuffed into countably many pigeonholes, there will exist at least one pigeonhole having uncountably many pigeons stuffed into it.

This principle is not a generalization of the pigeonhole principle for finite sets however: It is in general false for finite sets. In technical terms it says that if A and B are finite sets such that any surjective function from A to B is not injective, then there exists an element of b of B such that there exists a bijection between the preimage of b and A. This is a quite different statement, and is absurd for large finite cardinalities.

Quantum mechanics

Yakir Aharonov et al. has demonstrated mathematically the pigeonhole principle may be violated in quantum mechanics, and proposed interferometric experiments to test the pigeonhole principle in quantum mechanics.

See also

- Combinatorial principles

- Combinatorial proof

- Dedekind-infinite set

- Hilbert's paradox of the Grand Hotel

- Multinomial theorem

- Pumping lemma for regular languages

- Ramsey's theorem

- Pochhammer symbol

Notes

- 1 2 3 Herstein 1964, p. 90

- ↑ Jeff Miller, Peter Flor, Gunnar Berg, and Julio González Cabillón. "Pigeonhole principle". In Jeff Miller (ed.) Earliest Known Uses of Some of the Words of Mathematics. Electronic document, retrieved November 11, 2006

- ↑ Fletcher & Patty 1987, p. 27

- ↑ To avoid a slightly messier presentation we assume that "people" in this example only refers to people who are not bald.

- ↑ Grimaldi 1994, p. 277

- ↑ Brualdi 2010, p. 70

- ↑ Brualdi 2010, p. 74 Theorem 3.2.1

- ↑ In the lead section this was presented with the substitutions m = n and k = r − 1.

References

- Brualdi, Richard A. (2010), Introductory Combinatorics (5th ed.), Pentice Hall, ISBN 978-0-13-602040-0

- Fletcher, Peter; Patty, C.Wayne (1987), Foundations of Higher Mathematics, PWS-Kent, ISBN 0-87150-164-3

- Grimaldi, Ralph P. (1994), Discrete and Combinatorial Mathematics: An Applied Introduction (3rd ed.), ISBN 978-0-201-54983-6

- Herstein, I. N. (1964), Topics In Algebra, Waltham: Blaisdell Publishing Company, ISBN 978-1114541016

External links

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Dirichlet box principle", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

- "The strange case of The Pigeon-hole Principle"; Edsger Dijkstra investigates interpretations and reformulations of the principle.

- "The Pigeon Hole Principle"; Elementary examples of the principle in use by Larry Cusick.

- "Pigeonhole Principle from Interactive Mathematics Miscellany and Puzzles"; basic Pigeonhole Principle analysis and examples by Alexander Bogomolny.

- "16 fun applications of the pigeonhole principle"; Interesting facts derived by the principle.