Dirichlet's theorem on arithmetic progressions

In number theory, Dirichlet's theorem, also called the Dirichlet prime number theorem, states that for any two positive coprime integers a and d, there are infinitely many primes of the form a + nd, where n is a non-negative integer. In other words, there are infinitely many primes which are congruent to a modulo d. The numbers of the form a + nd form an arithmetic progression

and Dirichlet's theorem states that this sequence contains infinitely many prime numbers. The theorem extends Euclid's theorem that there are infinitely many prime numbers. Stronger forms of Dirichlet's theorem state that for any such arithmetic progression, the sum of the reciprocals of the prime numbers in the progression diverges and that different such arithmetic progressions with the same modulus have approximately the same proportions of primes. Equivalently, the primes are evenly distributed (asymptotically) among the congruence classes modulo d containing a's coprime to d.

Dirichlet's theorem does not require that the sequence contains only prime numbers and deals with infinite sequences. For finite sequences, there exist arbitrarily long arithmetic progressions of primes, a theorem known as the Green–Tao theorem.

Examples

An integer is a prime for the Gaussian integers if either the square of its modulus is a prime number (in the normal sense) or one of its parts is zero and the absolute value of the other is a prime that is congruent to 3 modulo 4. The primes (in the normal sense) of the type 4n + 3 are (sequence A002145 in OEIS)

- 3, 7, 11, 19, 23, 31, 43, 47, 59, 67, 71, 79, 83, 103, 107, 127, 131, 139, 151, 163, 167, 179, 191, 199, 211, 223, 227, 239, 251, 263, 271, 283, ...

They correspond to the following values of n: (sequence A095278 in OEIS)

- 0, 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 10, 11, 14, 16, 17, 19, 20, 25, 26, 31, 32, 34, 37, 40, 41, 44, 47, 49, 52, 55, 56, 59, 62, 65, 67, 70, 76, 77, 82, 86, 89, 91, 94, 95, ...

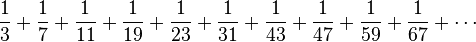

The strong form of Dirichlet's theorem implies that

is a divergent series.

The following table lists several arithmetic progressions with infinitely many primes and the first few ones in each of them.

| Arithmetic progression | First 10 of infinitely many primes | OEIS sequence |

|---|---|---|

| 2n + 1 | 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23, 29, 31, … | A065091 |

| 4n + 1 | 5, 13, 17, 29, 37, 41, 53, 61, 73, 89, … | A002144 |

| 4n + 3 | 3, 7, 11, 19, 23, 31, 43, 47, 59, 67, … | A002145 |

| 6n + 1 | 7, 13, 19, 31, 37, 43, 61, 67, 73, 79, … | A002476 |

| 6n + 5 | 5, 11, 17, 23, 29, 41, 47, 53, 59, 71, … | A007528 |

| 8n + 1 | 17, 41, 73, 89, 97, 113, 137, 193, 233, 241, … | A007519 |

| 8n + 3 | 3, 11, 19, 43, 59, 67, 83, 107, 131, 139, … | A007520 |

| 8n + 5 | 5, 13, 29, 37, 53, 61, 101, 109, 149, 157, … | A007521 |

| 8n + 7 | 7, 23, 31, 47, 71, 79, 103, 127, 151, 167, … | A007522 |

| 10n + 1 | 11, 31, 41, 61, 71, 101, 131, 151, 181, 191, … | A030430 |

| 10n + 3 | 3, 13, 23, 43, 53, 73, 83, 103, 113, 163, … | A030431 |

| 10n + 7 | 7, 17, 37, 47, 67, 97, 107, 127, 137, 157, … | A030432 |

| 10n + 9 | 19, 29, 59, 79, 89, 109, 139, 149, 179, 199, … | A030433 |

| 12n + 1 | 13, 37, 61, 73, 97, 109, 157, 181, 193, 229, ... | A068228 |

| 12n + 5 | 5, 17, 29, 41, 53, 89, 101, 113, 137, 149, ... | A040117 |

| 12n + 7 | 7, 19, 31, 43, 67, 79, 103, 127, 139, 151, ... | A068229 |

| 12n + 11 | 11, 23, 47, 59, 71, 83, 107, 131, 167, 179, ... | A068231 |

Distribution

Since the primes thin out, on average, in accordance with the prime number theorem, the same must be true for the primes in arithmetic progressions. One naturally then asks about the way the primes are shared between the various arithmetic progressions for a given value of d (there are d of those, essentially, if we don't distinguish two progressions sharing almost all their terms). The answer is given in this form: the number of feasible progressions modulo d — those where a and d do not have a common factor > 1 — is given by Euler's totient function

Further, the proportion of primes in each of those is

For example if d is a prime number q, each of the q − 1 progressions, other than

contains a proportion 1/(q − 1) of the primes.

When compared to each other, progressions with a quadratic nonresidue remainder have typically slightly more elements than those with a quadratic residue remainder (Chebyshev's bias).

History

Euler stated that every arithmetic progression beginning with 1 contains an infinite number of primes. The theorem in the above form was first conjectured by Legendre in his attempted unsuccessful proofs of quadratic reciprocity and proved by Dirichlet (1837) with Dirichlet L-series. The proof is modeled on Euler's earlier work relating the Riemann zeta function to the distribution of primes. The theorem represents the beginning of rigorous analytic number theory.

Atle Selberg (1946) gave an elementary proof.

Proof

Dirichlet's theorem is proved by showing that the value of the Dirichlet L-function (of a non-trivial character) at 1 is nonzero. The proof of this statement requires some calculus and analytic number theory (Serre 1973). In the particular case a = 1 (i.e., concerning the primes that are congruent to 1 modulo some n) can be proven by analyzing the splitting behavior of primes in cyclotomic extensions, without making use of calculus (Neukirch 1999).

Generalizations

The Bunyakovsky conjecture generalizes Dirichlet's theorem to higher-order polynomials. Whether or not even simple quadratic polynomials such as x2 + 1 (known from Landau's fourth problem) attain infinitely many prime values is an important open problem.

In algebraic number theory, Dirichlet's theorem generalizes to Chebotarev's density theorem.

Linnik's theorem (1944) concerns the size of the smallest prime in a given arithmetic progression. Linnik proved that the progression a + nd (as n ranges through the positive integers) contains a prime of magnitude at most cdL for absolute constants c and L. Subsequent researchers have reduced L to 5.

An analogue of Dirichlet's theorem holds in the framework of dynamical systems (T. Sunada and A. Katsuda, 1990).

See also

- Bombieri–Vinogradov theorem

- Brun–Titchmarsh theorem

- Siegel–Walfisz theorem

- Dirichlet's approximation theorem

References

- Apostol, Tom M. (1976), Introduction to analytic number theory, Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics, New York-Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-90163-3, MR 0434929, Zbl 0335.10001

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Dirichlet's Theorem", MathWorld.

- Chris Caldwell, "Dirichlet's Theorem on Primes in Arithmetic Progressions" at the Prime Pages.

- Dirichlet, P. G. L. (1837), "Beweis des Satzes, dass jede unbegrenzte arithmetische Progression, deren erstes Glied und Differenz ganze Zahlen ohne gemeinschaftlichen Factor sind, unendlich viele Primzahlen enthält", Abhand. Ak. Wiss. Berlin 48

- Neukirch, Jürgen (1999), Algebraic number theory. Translated from the 1992 German original and with a note by Norbert Schappacher, Grundlehren der Mathematischen Wissenschaften [Fundamental Principles of Mathematical Sciences] 322, Berlin: Springer-Verlag, Section VII.6 and Exercise I.10.1, ISBN 3-540-65399-6, MR 1697859, Zbl 0956.11021.

- Selberg, Atle (1949), "An elementary proof of Dirichlet's theorem about primes in an arithmetic progression", Annals of Mathematics 50 (2): 297–304, doi:10.2307/1969454, JSTOR 1969454, Zbl 0036.30603.

- Serre, Jean-Pierre (1973), A course in arithmetic, Graduate Texts in Mathematics 7, New York-Heidelberg-Berlin: Springer- Verlag, ISBN 3-540-90040-3, Zbl 0256.12001.

- Sunada, Toshikazu; Katsuda, Atsushi (1990), "Closed orbits in homology classes", Publ. Math. IHES 71: 5–32.

External links

- Scans of the original paper in German

- Dirichlet: There are infinitely many prime numbers in all arithmetic progressions with first term and difference coprime English translation of the original paper at the arXiv

- Dirichlet's Theorem by Jay Warendorff, Wolfram Demonstrations Project.