Directivity

| Part of a series on |

| Antennas |

|---|

|

|

Common types |

|

Radiation sources / regions |

In electromagnetics, directivity is a figure of merit, usually for an antenna. It measures the power density the antenna radiates in the direction of its strongest emission, versus the power density radiated by an ideal isotropic radiator (which emits uniformly in all directions) radiating the same total power.

An antenna's directivity is a component of its gain; the other component is its (electrical) efficiency. Directivity is an important measure because most emissions are intended to go in a particular direction or at least in a particular plane (horizontal or vertical); emissions in other directions or planes are wasteful (or worse).

The directivity of an actual antenna can vary from 1.76 dBi for a short dipole, to as much as 50 dBi for a large dish antenna.[1]

Definition

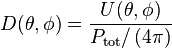

The directivity, D, of an antenna is the maximum value of its directive gain. Directive gain is represented as  , and compares the radiation intensity (power per unit solid angle)

, and compares the radiation intensity (power per unit solid angle)  that an antenna creates in a particular direction against the average value over all directions:

that an antenna creates in a particular direction against the average value over all directions:

Here  and

and  are the standard spherical coordinate angles,

are the standard spherical coordinate angles,  is the radiation intensity, which is the power density per unit solid angle, and

is the radiation intensity, which is the power density per unit solid angle, and  is the total radiated power. The quantities

is the total radiated power. The quantities  and

and  satisfy the relation:

satisfy the relation:

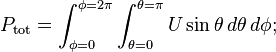

that is, the total radiated power  is the power per unit solid angle

is the power per unit solid angle  integrated over a spherical surface. Since there are 4π steradians on the surface of a sphere, the quantity

integrated over a spherical surface. Since there are 4π steradians on the surface of a sphere, the quantity  represents the average power per unit solid angle.

represents the average power per unit solid angle.

In other words, directive gain is the radiation intensity of an antenna at a particular  coordinate combination divided by what the radiation intensity would have been had the antenna been an isotropic antenna radiating the same amount of total power into space.

coordinate combination divided by what the radiation intensity would have been had the antenna been an isotropic antenna radiating the same amount of total power into space.

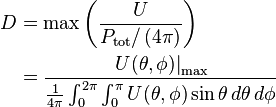

Directivity, then, is the maximum directive gain value found among all possible solid angles:

The word directivity is also sometimes used as a synonym for directive gain. This usage is readily understood, as the direction will be specified, or directional dependence implied. Later editions of the IEEE Dictionary[2] specifically endorse this usage; nevertheless it has yet to be universally adopted.

Relation to beam width

The beam solid angle, represented as  , is defined as the solid angle which all power would flow through if the antenna radiation intensity were constant and maximum value. If the beam solid angle is known, then directivity can be calculated as:

, is defined as the solid angle which all power would flow through if the antenna radiation intensity were constant and maximum value. If the beam solid angle is known, then directivity can be calculated as:

...which simply calculates the ratio of the beam solid angle to the total surface area of the sphere it intersects.

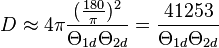

The beam solid angle can be approximated for antennas with one narrow major lobe and very negligible minor lobes, by simply multiplying the half-power beamwidths (in radians) in two perpendicular planes. The half-power beamwidth is simply the angle in which the radiation intensity is at least half of the peak radiation intensity.

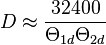

The same calculations can be performed in degrees rather than in radians:

...where  is the half-power beamwidth in one plane (degrees) and

is the half-power beamwidth in one plane (degrees) and  is the half-power beamwidth in a plane at a right angle to the other (degrees).

is the half-power beamwidth in a plane at a right angle to the other (degrees).

In planar arrays, a better approximation is:

Expression in decibels

The directivity is rarely expressed as the unitless number  . Rather, the directivity is usually expressed as a decibel comparison to a reference antenna:

. Rather, the directivity is usually expressed as a decibel comparison to a reference antenna:

The reference antenna is usually the theoretical perfect isotropic radiator which radiates uniformly in all directions and hence has a directivity of 1. The calculation is therefore simplified to:

Another common reference antenna is the theoretical perfect half-wave dipole which radiates perpendicular to itself with a directivity of 1.64:

Accounting for polarization

When polarization is taken under consideration, three additional measures can be calculated:

Partial directive gain

Partial directive gain is the power density in a particular direction and for a particular component of the polarization, divided by the average power density for all directions and all polarizations. For any pair of orthogonal polarizations (such as left-hand-circular and right-hand-circular), the individual power densities simply add to give the total power density. Thus, if expressed as dimensionless ratios rather than in dB, the total directive gain is equal to the sum of the two partial directive gains.[2]

Partial directivity

Partial directivity is calculated in the same manner as the partial directive gain, but without consideration of antenna efficiency (i.e. assuming a lossless antenna). It is similarly additive for orthogonal polarizations.

Partial gain

Partial gain is calculated in the same manner as gain, but considering only a certain polarization. It is similarly additive for orthogonal polarizations.

In other areas

The term directivity is also used with other systems.

With directional couplers, directivity is a measure of the difference in dB of the power output at a coupled port, when power is transmitted in the desired direction, to the power output at the same coupled port when the same amount of power is transmitted in the opposite direction.[3]

In acoustics, it is used as a measure of the radiation pattern from a source indicating how much of the total energy from the source is radiating in a particular direction. In electro-acoustics, these patterns commonly include omnidirectional, cardioid and hyper-cardioid microphone polar patterns. A loudspeaker with a high degree of directivity (narrow dispersion pattern) can be said to have a high Q.[4]

References

- ↑ Antenna Tutorial

- 1 2 Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, “The IEEE standard dictionary of electrical and electronics terms”; 6th ed. New York, N.Y., Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, c1997. IEEE Std 100-1996. ISBN 1-55937-833-6 [ed. Standards Coordinating Committee 10, Terms and Definitions; Jane Radatz, (chair)]

- ↑ App note, Mini-Circuits directional couplers

- ↑ Rane Professional Audio Reference Home

- Coleman, Christopher (2004). "Basic Concepts". An Introduction to Radio Frequency Engineering. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-83481-3.

![D_{dB} = 10 \cdot \log_{10}\left[\frac{D}{D_{reference}}\right]](../I/m/b515478c1af15449b7b95401a71514ac.png)

![D_{dBi} = 10 \cdot \log_{10}\left[D\right]](../I/m/e0b8448bf0637f8362c0719bcfa1f93a.png)

![D_{dBd} = 10 \cdot \log_{10}\left[\frac{D}{1.64}\right]](../I/m/ad501891fb46d0d2e196f7ab3bcfb973.png)