Growth medium

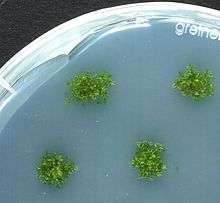

A growth medium or culture medium is a liquid or gel designed to support the growth of microorganisms or cells,[1] or small plants like the moss Physcomitrella patens.[2] There are different types of media for growing different types of cells.[3]

There are two major types of growth media: those used for cell culture, which use specific cell types derived from plants or animals, and microbiological culture, which are used for growing microorganisms, such as bacteria or yeast. The most common growth media for microorganisms are nutrient broths and agar plates; specialized media are sometimes required for microorganism and cell culture growth.[1] Some organisms, termed fastidious organisms, require specialized environments due to complex nutritional requirements. Viruses, for example, are obligate intracellular parasites and require a growth medium containing living cells.

Types

The most common growth media for microorganisms are nutrient broths (liquid nutrient medium) or LB medium (Lysogeny Broth). Liquid media are often mixed with agar and poured via sterile media dispenser into Petri dishes to solidify. These agar plates provide a solid medium on which microbes may be cultured. They remain solid, as very few bacteria are able to decompose agar (the exception being some species in the following genera: Cytophaga, Flavobacterium, Bacillus, Pseudomonas, and Alcaligenes). Bacteria grown in liquid cultures often form colloidal suspensions.[4][5]

The difference between growth media used for cell culture and those used for microbiological culture is that cells derived from whole organisms and grown in culture often cannot grow without the addition of, for instance, hormones or growth factors which usually occur in vivo.[6] In the case of animal cells, this difficulty is often addressed by the addition of blood serum or a synthetic serum replacement to the medium. In the case of microorganisms, there are no such limitations, as they are often unicellular organisms. One other major difference is that animal cells in culture are often grown on a flat surface to which they attach, and the medium is provided in a liquid form, which covers the cells. In contrast, bacteria such as Escherichia coli may be grown on solid media or in liquid media.

An important distinction between growth media types is that of defined versus undefined media.[1] A defined medium will have known quantities of all ingredients. For microorganisms, they consist of providing trace elements and vitamins required by the microbe and especially a defined carbon source and nitrogen source. Glucose or glycerol are often used as carbon sources, and ammonium salts or nitrates as inorganic nitrogen sources. An undefined medium has some complex ingredients, such as yeast extract or casein hydrolysate, which consist of a mixture of many, many chemical species in unknown proportions. Undefined media are sometimes chosen based on price and sometimes by necessity – some microorganisms have never been cultured on defined media.

A good example of a growth medium is the wort used to make beer. The wort contains all the nutrients required for yeast growth, and under anaerobic conditions, alcohol is produced. When the fermentation process is complete, the combination of medium and dormant microbes, now beer, is ready for consumption.

Nutrient media

Nutrient media contain all the elements that most bacteria need for growth and are non-selective, so they are used for the general cultivation and maintenance of bacteria kept in laboratory culture collections.

An undefined medium (also known as a basal or complex medium) is a medium that contains:

- a carbon source such as glucose for bacterial growth

- water

- various salts needed for bacterial growth

- a source of amino acids and nitrogen (e.g., beef, yeast extract)

- This is an undefined medium because the amino acid source contains a variety of compounds with the exact composition being unknown.

A defined medium (also known as chemically defined medium or synthetic medium) is a medium in which

- all the chemicals used are known

- no yeast, animal or plant tissue is present

Some examples of nutrient media include:

Minimal media

Minimal media are those that contain the minimum nutrients possible for colony growth, generally without the presence of amino acids, and are often used by microbiologists and geneticists to grow "wild type" microorganisms. Minimal media can also be used to select for or against recombinants or exconjugants.

Minimal medium typically contains:

- a carbon source for bacterial growth, which may be a sugar such as glucose, or a less energy-rich source like succinate

- various salts, which may vary among bacteria species and growing conditions; these generally provide essential elements such as magnesium, nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur to allow the bacteria to synthesize protein and nucleic acid

- water

Supplementary minimal media are a type of minimal media that also contains a single selected agent, usually an amino acid or a sugar. This supplementation allows for the culturing of specific lines of auxotrophic recombinants.

Selective media

Selective media are used for the growth of only selected microorganisms. For example, if a microorganism is resistant to a certain antibiotic, such as ampicillin or tetracycline, then that antibiotic can be added to the medium in order to prevent other cells, which do not possess the resistance, from growing. Media lacking an amino acid such as proline in conjunction with E. coli unable to synthesize it were commonly used by geneticists before the emergence of genomics to map bacterial chromosomes.

Selective growth media are also used in cell culture to ensure the survival or proliferation of cells with certain properties, such as antibiotic resistance or the ability to synthesize a certain metabolite. Normally, the presence of a specific gene or an allele of a gene confers upon the cell the ability to grow in the selective medium. In such cases, the gene is termed a marker.

Selective growth media for eukaryotic cells commonly contain neomycin to select cells that have been successfully transfected with a plasmid carrying the neomycin resistance gene as a marker. Gancyclovir is an exception to the rule as it is used to specifically kill cells that carry its respective marker, the Herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (HSV TK).

Examples of selective media include:

- Eosin methylene blue (EMB) contains dyes that are toxic for Gram positive bacteria and bile salt which is toxic for Gram negative bacteria other than coliforms. EMB is the selective and differential medium for coliforms

- YM (yeast and mold) which has a low pH, deterring bacterial growth

- MacConkey agar for Gram-negative bacteria

- Hektoen enteric agar (HE) which is selective for Gram-negative bacteria

- Mannitol salt agar (MSA) which is selective for Gram-positive bacteria and differential for mannitol

- Terrific Broth (TB) is used with glycerol in cultivating recombinant strains of Escherichia coli.

- Xylose lysine desoxycholate (XLD), which is selective for Gram-negative bacteria

- Buffered charcoal yeast extract agar, which is selective for certain gram-negative bacteria, especially Legionella pneumophila

- Baird–Parker agar for Gram-positive Staphylococci

Differential media

Differential media or indicator media distinguish one microorganism type from another growing on the same media.[7] This type of media uses the biochemical characteristics of a microorganism growing in the presence of specific nutrients or indicators (such as neutral red, phenol red, eosin y, or methylene blue) added to the medium to visibly indicate the defining characteristics of a microorganism. This type of media is used for the detection of microorganisms and by molecular biologists to detect recombinant strains of bacteria.

Examples of differential media include:

- Blood agar (used in strep tests), which contains bovine heart blood that becomes transparent in the presence of hemolytic Streptococcus

- Eosin methylene blue (EMB), which is differential for lactose fermentation

- Granada medium (EMB), which is selective and differential for Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B streptococcus, GBS). GBS grows as distinctive red colonies in this medium

- MacConkey agar (MCK), which is differential for lactose fermentation

- Mannitol salt agar (MSA), which is differential for mannitol fermentation

- X-gal plates, which are differential for lac operon mutants

Transport media

Transport media should fulfill the following criteria:

- temporary storage of specimens being transported to the laboratory for cultivation.

- maintain the viability of all organisms in the specimen without altering their concentration.

- contain only buffers and salt.

- lack of carbon, nitrogen, and organic growth factors so as to prevent microbial multiplication.

- transport media used in the isolation of anaerobes must be free of molecular oxygen.

Examples of transport media include:

- Thioglycolate broth for strict anaerobes.

- Stuart transport medium – a non-nutrient soft agar gel containing a reducing agent to prevent oxidation, and charcoal to neutralise

- Certain bacterial inhibitors- for gonococci, and buffered glycerol saline for enteric bacilli.

- Venkataraman Ramakrishna(VR) medium for V. cholerae.

Enriched media

Enriched media contain the nutrients required to support the growth of a wide variety of organisms, including some of the more fastidious ones. They are commonly used to harvest as many different types of microbes as are present in the specimen. Blood agar is an enriched medium in which nutritionally rich whole blood supplements the basic nutrients. Chocolate agar is enriched with heat-treated blood (40–45 °C), which turns brown and gives the medium the color for which it is named.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Madigan M, Martinko J (editors). (2005). Brock Biology of Microorganisms (11th ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-144329-1.

- ↑ Birgit Hadeler, Sirkka Scholz, Ralf Reski (1995) Gelrite and agar differently influence cytokinin-sensitivity of a moss. Journal of Plant Physiology 146, 369–371

- ↑ Ryan KJ, Ray CG (editors) (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-8385-8529-9.

- ↑ Hans Günter Schlegel (1993). General Microbiology. Cambridge University. p. 459. ISBN 978-0-521-43980-0. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ↑ Parija, Shubhash Chandra (1 January 2009). Textbook of Microbiology & Immunology. Elsevier India. p. 45. ISBN 978-81-312-2163-1. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ↑ Cooper GM (2000). "Tools of Cell Biology". The cell: a molecular approach. Washington, D.C: ASM Press. ISBN 0-87893-106-6.

- ↑ Washington JA (1996). "Principles of Diagnosis". Baron's Medical Microbiology (Baron S et al., eds.) (4th ed.). Univ of Texas Medical Branch. ISBN 0-9631172-1-1.

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|