Differential entropy

Differential entropy (also referred to as continuous entropy) is a concept in information theory that extends the idea of (Shannon) entropy, a measure of average surprisal of a random variable, to continuous probability distributions.

Definition

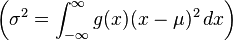

Let X be a random variable with a probability density function f whose support is a set  . The differential entropy h(X) or h(f) is defined as

. The differential entropy h(X) or h(f) is defined as

.

.

For probability distributions which don't have an explicit density function expression, but have an explicit quantile function expression, Q(p), then h(Q) can be defined in terms of the derivative of Q(p) i.e. the quantile density function Q'(p) as [1]

.

.

As with its discrete analog, the units of differential entropy depend on the base of the logarithm, which is usually 2 (i.e., the units are bits). See logarithmic units for logarithms taken in different bases. Related concepts such as joint, conditional differential entropy, and relative entropy are defined in a similar fashion. Unlike the discrete analog, the differential entropy has an offset that depends on the units used to measure X.[2] For example, the differential entropy of a quantity measured in millimeters will be log(1000) more than the same quantity measured in meters; a dimensionless quantity will have differential entropy of log(1000) more than the same quantity divided by 1000.

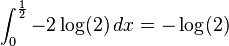

One must take care in trying to apply properties of discrete entropy to differential entropy, since probability density functions can be greater than 1. For example, Uniform(0,1/2) has negative differential entropy

.

.

Thus, differential entropy does not share all properties of discrete entropy.

Note that the continuous mutual information I(X;Y) has the distinction of retaining its fundamental significance as a measure of discrete information since it is actually the limit of the discrete mutual information of partitions of X and Y as these partitions become finer and finer. Thus it is invariant under non-linear homeomorphisms (continuous and uniquely invertible maps) ,[3] including linear [4] transformations of X and Y, and still represents the amount of discrete information that can be transmitted over a channel that admits a continuous space of values.

Properties of differential entropy

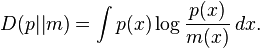

- For densities f and g, the Kullback–Leibler divergence D(f||g) is nonnegative with equality if f = g almost everywhere. Similarly, for two random variables X and Y, I(X;Y) ≥ 0 and h(X|Y) ≤ h(X) with equality if and only if X and Y are independent.

- The chain rule for differential entropy holds as in the discrete case

.

.

- Differential entropy is translation invariant, i.e., h(X + c) = h(X) for a constant c.

- Differential entropy is in general not invariant under arbitrary invertible maps. In particular, for a constant a, h(aX) = h(X) + log|a|. For a vector valued random variable X and a matrix A, h(A X) = h(X) + log|det(A)|.

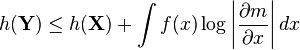

- In general, for a transformation from a random vector to another random vector with same dimension Y = m(X), the corresponding entropies are related via

- where

is the Jacobian of the transformation m. The above inequality becomes an equality if the transform is a bijection. Furthermore, when m is a rigid rotation, translation, or combination thereof, the Jacobian determinant is always 1, and h(Y) = h(X).

is the Jacobian of the transformation m. The above inequality becomes an equality if the transform is a bijection. Furthermore, when m is a rigid rotation, translation, or combination thereof, the Jacobian determinant is always 1, and h(Y) = h(X).

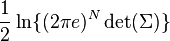

- If a random vector X in Rn has mean zero and covariance matrix K,

![h(\mathbf{X}) \leq \frac{1}{2} \log[(2\pi e)^n \det{K}]](../I/m/539606fc900cd51e9374f0a1adf2b6dd.png) with equality if and only if X is jointly gaussian (see below).

with equality if and only if X is jointly gaussian (see below).

However, differential entropy does not have other desirable properties:

- It is not invariant under change of variables, and is therefore most useful with dimensionless variables.

- It can be negative.

A modification of differential entropy that addresses these drawbacks is the relative information entropy, also known as the Kullback–Leibler divergence, which includes an invariant measure factor (see limiting density of discrete points).

Maximization in the normal distribution

With a normal distribution, differential entropy is maximized for a given variance. The following is a proof that a Gaussian variable has the largest entropy amongst all random variables of equal variance, or, alternatively, that the maximum entropy distribution under constraints of mean and variance is the Gaussian.

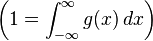

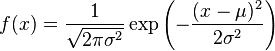

Let g(x) be a Gaussian PDF with mean μ and variance σ2 and f(x) an arbitrary PDF with the same variance. Since differential entropy is translation invariant we can assume that f(x) has the same mean of μ as g(x).

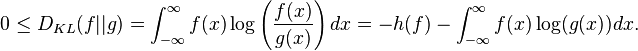

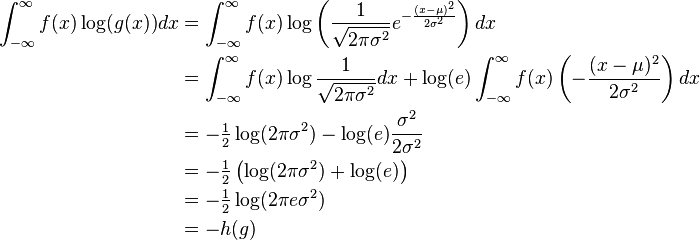

Consider the Kullback–Leibler divergence between the two distributions

Now note that

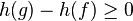

because the result does not depend on f(x) other than through the variance. Combining the two results yields

with equality when g(x) = f(x) following from the properties of Kullback–Leibler divergence.

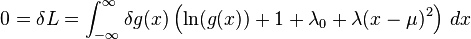

This result may also be demonstrated using the variational calculus. A Lagrangian function with two Lagrangian multipliers may be defined as:

where g(x) is some function with mean μ. When the entropy of g(x) is at a maximum and the constraint equations, which consist of the normalization condition  and the requirement of fixed variance

and the requirement of fixed variance  , are both satisfied, then a small variation δg(x) about g(x) will produce a variation δL about L which is equal to zero:

, are both satisfied, then a small variation δg(x) about g(x) will produce a variation δL about L which is equal to zero:

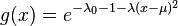

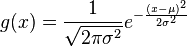

Since this must hold for any small δg(x), the term in brackets must be zero, and solving for g(x) yields:

Using the constraint equations to solve for λ0 and λ yields the normal distribution:

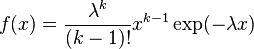

Example: Exponential distribution

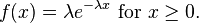

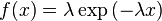

Let X be an exponentially distributed random variable with parameter λ, that is, with probability density function

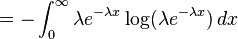

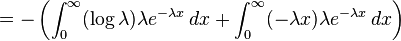

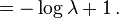

Its differential entropy is then

|

|

| |

![= -\log \lambda \int_0^\infty f(x)\,dx + \lambda E[X]](../I/m/111f140bd026b08482d9840334508dfd.png) | |

|

Here,  was used rather than

was used rather than  to make it explicit that the logarithm was taken to base e, to simplify the calculation.

to make it explicit that the logarithm was taken to base e, to simplify the calculation.

Differential entropies for various distributions

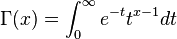

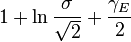

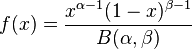

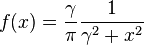

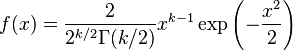

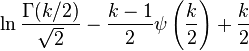

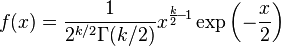

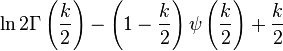

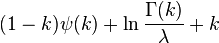

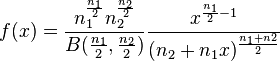

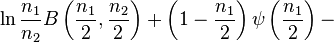

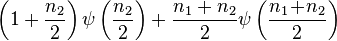

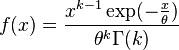

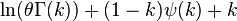

In the table below  is the gamma function,

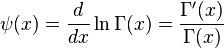

is the gamma function,  is the digamma function,

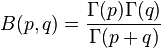

is the digamma function,  is the beta function, and γE is Euler's constant.[5]

is the beta function, and γE is Euler's constant.[5]

| Distribution Name | Probability density function (pdf) | Entropy in nats | Support |

|---|---|---|---|

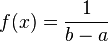

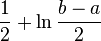

| Uniform |  |  | ![[a,b]\,](../I/m/7f3408c72246eece3d5542fc853ce417.png) |

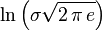

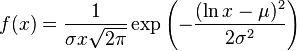

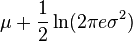

| Normal |  |  |  |

| Exponential |  |  |  |

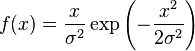

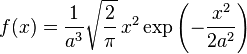

| Rayleigh |  |  |  |

| Beta |  for for  | ![\ln B(\alpha,\beta) - (\alpha-1)[\psi(\alpha) - \psi(\alpha +\beta)]\,](../I/m/34dad70ac931f39ca86988327d521608.png) ![- (\beta-1)[\psi(\beta) - \psi(\alpha + \beta)] \,](../I/m/618397c7e55ce77406a00a6d8d7002a7.png) | ![[0,1]\,](../I/m/d09694b77d8a3a03f6879fa37f09d0b0.png) |

| Cauchy |  |  |  |

| Chi |  |  |  |

| Chi-squared |  |  |  |

| Erlang |  |  |  |

| F |  |   |  |

| Gamma |  |  |  |

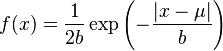

| Laplace |  |  |  |

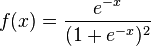

| Logistic |  |  |  |

| Lognormal |  |  |  |

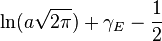

| Maxwell–Boltzmann |  |  |  |

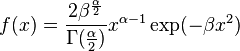

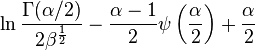

| Generalized normal |  |  |  |

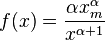

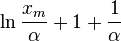

| Pareto |  |  |  |

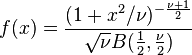

| Student's t |  |  |  |

| Triangular | ![f(x) = \begin{cases}

\frac{2(x-a)}{(b-a)(c-a)} & \mathrm{for\ } a \le x \leq c, \\[4pt]

\frac{2(b-x)}{(b-a)(b-c)} & \mathrm{for\ } c < x \le b, \\[4pt]

\end{cases}](../I/m/47143d7381bbd978d72f1ae19478810b.png) |  | ![[0,1]\,](../I/m/d09694b77d8a3a03f6879fa37f09d0b0.png) |

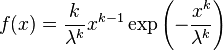

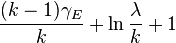

| Weibull |  |  |  |

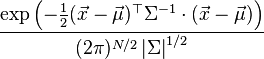

| Multivariate normal |   |  |  |

(Many of the differential entropies are from.[6]

Variants

As described above, differential entropy does not share all properties of discrete entropy. For example, the differential entropy can be negative; also it is not invariant under continuous coordinate transformations. Edwin Thompson Jaynes showed in fact that the expression above is not the correct limit of the expression for a finite set of probabilities.[7]

A modification of differential entropy adds an invariant measure factor to correct this, (see limiting density of discrete points). If m(x) is further constrained to be a probability density, the resulting notion is called relative entropy in information theory:

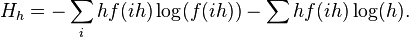

The definition of differential entropy above can be obtained by partitioning the range of X into bins of length h with associated sample points ih within the bins, for X Riemann integrable. This gives a quantized version of X, defined by Xh = ih if ih ≤ X ≤ (i+1)h. Then the entropy of Xh is

The first term on the right approximates the differential entropy, while the second term is approximately −log(h). Note that this procedure suggests that the entropy in the discrete sense of a continuous random variable should be ∞.

See also

- Information entropy

- Information theory

- Limiting density of discrete points

- Self-information

- Kullback–Leibler divergence

- Entropy estimation

References

- ↑ Vasicek, Oldrich (1976), "A Test for Normality Based on Sample Entropy", Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B 38 (1): 54–59.

- ↑ Pages 183-184, Gibbs, Josiah Willard (1902). Elementary Principles in Statistical Mechanics, developed with especial reference to the rational foundation of thermodynamics. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- ↑ Kraskov, Alexander; Stögbauer, Grassberger (2004). "Estimating mutual information". Phys. Rev. E 60: 066138. arXiv:cond-mat/0305641. Bibcode:2004PhRvE..69f6138K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.69.066138.

- ↑ Fazlollah M. Reza (1994) [1961]. An Introduction to Information Theory. Dover Publications, Inc., New York. ISBN 0-486-68210-2.

- ↑ Park, Sung Y.; Bera, Anil K. (2009). "Maximum entropy autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity model" (PDF). Journal of Econometrics (Elsevier): 219–230. Retrieved 2011-06-02.

- ↑ Lazo, A. and P. Rathie (1978). "On the entropy of continuous probability distributions". Information Theory, IEEE Transactions on. 24(1): 120–122. doi:10.1109/TIT.1978.1055832.

- ↑ Jaynes, E.T. (1963). "Information Theory And Statistical Mechanics" (PDF). Brandeis University Summer Institute Lectures In Theoretical Physics 3 (sect. 4b): 181–218.

- Thomas M. Cover, Joy A. Thomas. Elements of Information Theory New York: Wiley, 1991. ISBN 0-471-06259-6

External links

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Differential entropy", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

- Differential entropy at PlanetMath.org.