Delay differential equation

| Differential equations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Navier–Stokes differential equations used to simulate airflow around an obstruction. | |||||

| Classification | |||||

|

Types

|

|||||

|

Relation to processes |

|||||

| Solution | |||||

|

General topics |

|||||

In mathematics, delay differential equations (DDEs) are a type of differential equation in which the derivative of the unknown function at a certain time is given in terms of the values of the function at previous times. DDEs are also called time-delay systems, systems with aftereffect or dead-time, hereditary systems, equations with deviating argument, or differential-difference equations. They belong to the class of systems with the functional state, i.e. partial differential equations (PDEs) which are infinite dimensional, as opposed to ordinary differential equations (ODEs) having a finite dimensional state vector. Four points may give a possible explanation of the popularity of DDEs.[1] (1) Aftereffect is an applied problem: it is well known that, together with the increasing expectations of dynamic performances, engineers need their models to behave more like the real process. Many processes include aftereffect phenomena in their inner dynamics. In addition, actuators, sensors, communication networks that are now involved in feedback control loops introduce such delays. Finally, besides actual delays, time lags are frequently used to simplify very high order models. Then, the interest for DDEs keeps on growing in all scientific areas and, especially, in control engineering. (2) Delay systems are still resistant to many classical controllers: one could think that the simplest approach would consist in replacing them by some finite-dimensional approximations. Unfortunately, ignoring effects which are adequately represented by DDEs is not a general alternative: in the best situation (constant and known delays), it leads to the same degree of complexity in the control design. In worst cases (time-varying delays, for instance), it is potentially disastrous in terms of stability and oscillations. (3) Delay properties are also surprising since several studies have shown that voluntary introduction of delays can also benefit the control. (4) In spite of their complexity, DDEs however often appear as simple infinite-dimensional models in the very complex area of partial differential equations (PDEs).

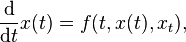

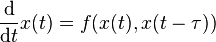

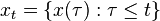

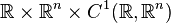

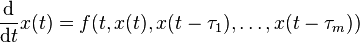

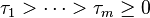

A general form of the time-delay differential equation for  is

is

where  represents the trajectory of the solution in the past. In this equation,

represents the trajectory of the solution in the past. In this equation,  is a functional operator from

is a functional operator from

to

to

Examples

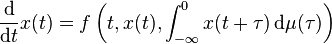

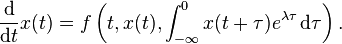

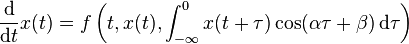

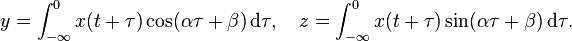

- Continuous delay

- Discrete delay

for

for  .

.

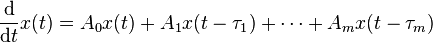

- Linear with discrete delays

- where

.

.

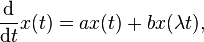

- Pantograph equation

- where a, b and λ are constants and 0 < λ < 1. This equation and some more general forms are named after the pantographs on trains.

Solving DDEs

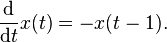

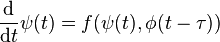

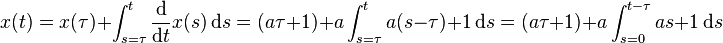

DDEs are mostly solved in a stepwise fashion with a principle called the method of steps. For instance, consider the DDE with a single delay

with given initial condition ![\phi\colon [-\tau,0]\rightarrow \mathbb{R}^n](../I/m/f65ae71eac617bd52f27614a75f18d55.png) . Then the solution on the interval

. Then the solution on the interval ![[0,\tau]](../I/m/e5ca7d91a93c00a665834ee1f8a1245b.png) is given by

is given by  which is the solution to the inhomogeneous initial value problem

which is the solution to the inhomogeneous initial value problem

,

,

with  . This can be continued for the successive intervals by using the solution to the previous interval as inhomogeneous term. In practice, the initial value problem is often solved numerically.

. This can be continued for the successive intervals by using the solution to the previous interval as inhomogeneous term. In practice, the initial value problem is often solved numerically.

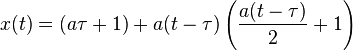

Example

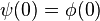

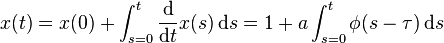

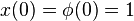

Suppose  and

and  . Then the initial value problem can be solved with integration,

. Then the initial value problem can be solved with integration,

,

,

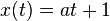

i.e.,  , where the initial condition is given by

, where the initial condition is given by  . Similarly, for the interval

. Similarly, for the interval

![t\in[\tau,2\tau]](../I/m/8b60b5ef05a88553de520541d00b0764.png) we integrate and fit the initial condition,

we integrate and fit the initial condition,

,

,

i.e.,  .

.

Reduction to ODE

In some cases, delay differential equations are equivalent to a system of ordinary differential equations.

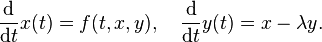

- Example 1 Consider an equation

- Introduce

to get a system of ODEs

to get a system of ODEs

- Example 2 An equation

- is equivalent to

- where

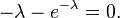

The characteristic equation

Similar to ODEs, many properties of linear DDEs can be characterized and analyzed using the characteristic equation.[2] The characteristic equation associated with the linear DDE with discrete delays

is

.

.

The roots λ of the characteristic equation are called characteristic roots or eigenvalues and the solution set is often referred to as the spectrum. Because of the exponential in the characteristic equation, the DDE has, unlike the ODE case, an infinite number of eigenvalues, making a spectral analysis more involved. The spectrum does however have a some properties which can be exploited in the analysis. For instance, even though there are an infinite number of eigenvalues, there are only a finite number of eigenvalues to the right of any vertical line in the complex plane.

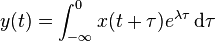

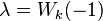

This characteristic equation is a nonlinear eigenproblem and there are many methods to compute the spectrum numerically.[3] In some special situations it is possible to solve the characteristic equation explicitly. Consider, for example, the following DDE:

The characteristic equation is

There are an infinite number of solutions to this equation for complex λ. They are given by

,

,

where Wk is the kth branch of the Lambert W function.

Software

In MATLAB, the function dde23 can be used to numerically solve delay differential equations.[4]

Notes

- ↑ Richard, Jean-Pierre (2003). "Time Delay Systems: An overview of some recent advances and open problems". Automatica 39 (10): 1667–1694. doi:10.1016/S0005-1098(03)00167-5.

- ↑ Michiels, Niculescu, 2007 Chapter 1

- ↑ Michiels, Niculescu, 2007Chapter 2

- ↑ Shampine, L. F.; Thompson, S. (2001). "Solving DDEs in Matlab" (PDF). Applied Numerical Mathematics 37 (4): 441. doi:10.1016/S0168-9274(00)00055-6.

References

- Bellman, Richard; Cooke, Kenneth L. (1963). Differential-difference equations. New York-London: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-084850-8.

- Driver, Rodney D. (1977). Ordinary and Delay Differential Equations. New York: Springer Verlag. ISBN 0-387-90231-7.

- Michiels, Wim and Niculescu, Silviu-Iulian (2007). Stability and stabilization of time-delay systems. An eigenvalue based approach. doi:10.1137/1.9780898718645. ISBN 978-0-89871-632-0.

- Briat, Corentin (2015). Linear Parameter-Varying and Time-Delay Systems. Analysis, Observation, Filtering & Control. Springer Verlag Heidelberg. ISBN 978-3-662-44049-0.

External links

- Delay-Differential Equations at Scholarpedia, curated by Skip Thompson.