Diabetic nephropathy

| Diabetic nephropathy | |

|---|---|

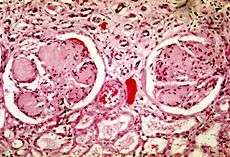

Scarred glomeruli in the kidney of a person with diabetic nephropathy | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | endocrinology |

| ICD-10 | E10.2, E11.2, E12.2, E13.2, E14.2 |

| ICD-9-CM | 250.4 |

| MedlinePlus | 000494 |

| MeSH | D003928 |

Diabetic nephropathy (or diabetic kidney disease[1]) is a progressive kidney disease caused by damage to the capillaries in the kidneys' glomeruli.[2] It is characterized by nephrotic syndrome and diffuse scarring of the glomeruli. It is due to longstanding diabetes mellitus, and is a prime reason for dialysis in many developed countries. It is classified as a small blood vessel complication of diabetes.[3]

Signs and symptoms

During its early course, diabetic nephropathy often has no symptoms.[4] Symptoms can take 5 to 10 years to appear after the kidney damage begins.[4] These late symptoms include severe tiredness, headaches, a general feeling of illness, nausea, vomiting, lack of appetite, itchy skin, and leg swelling.[4]

Causes

The cause of diabetic nephropathy is not well understood, but it is thought that high blood sugar, advanced glycation end product formation, and cytokines may be involved in the development of diabetic nephropathy.[5]

Kidney damage is likely if one or more of the following is present:[4]

- Poor control of blood glucose

- High blood pressure

- Type 1 diabetes mellitus (before age 20)

- History of cigarette smoking

- A family history of kidney problems

Mechanism

Diabetes causes a number of changes to the body's metabolism and blood circulation, which likely combine to produce excess reactive oxygen species (chemically reactive molecules containing oxygen). These changes damage the kidney's glomeruli (networks of tiny blood vessels), which leads to the hallmark feature of albumin in the urine (called albuminuria).[6] As diabetic nephropathy progresses, a structure in the glomeruli known as the glomerular filtration barrier (GFB) is increasingly damaged.[7] This barrier is composed of three layers including the fenestrated endothelium, the glomerular basement membrane, and the epithelial podocytes.[7] The GFB is responsible for the highly selective filtration of blood entering the kidney's glomeruli and normally only allows the passage of water, small molecules, and very small proteins (albumin does not pass through the intact GFB).[7]

Diagnosis

| CKD Stage[8] | eGFR level (mL/min/1.73 m2) |

|---|---|

| Stage 1 | ≥ 90 |

| Stage 2 | 60 – 89 |

| Stage 3 | 30 – 59 |

| Stage 4 | 15 – 29 |

| Stage 5 | < 15 |

Diagnosis is usually based on the measurement of high levels of albumin in the urine or evidence of reduced kidney function.[9] Albumin measurements are defined as follows:[10]

- Normal albuminuria: urinary albumin excretion <30 mg/24h;

- Microalbuminuria: urinary albumin excretion in the range of 30–299 mg/24h;

- Clinical (overt) albuminuria: urinary albumin excretion ≥300 mg/24h.

People with diabetes are recommended to have their albumin levels checked annually, beginning immediately after diagnosis for type 2 diabetics, and five years after diagnosis for type 1 diabetics.[9][11] To test kidney function, the person's estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) is measured from a blood sample. Normal eGFR ranges from 90 to 120 ml/min/1.73 m2.[12]

Treatment

The goals of treatment are to slow the progression of kidney damage and control related complications. The main treatment, once proteinuria is established, is ACE inhibitor medications, which usually reduce proteinuria levels and slow the progression of diabetic nephropathy.[13] Other issues that are important in the management of this condition include control of high blood pressure and blood sugar levels (see diabetes management), as well as the reduction of dietary salt intake.[14]

Prognosis

Diabetic nephropathy in type 2 diabetes can be more difficult to predict because the onset of diabetes is not usually well established. Without intervention, 20-40 percent of patients with type 2 diabetes/microalbuminuria, will evolve to macroalbuminuria.[15]

Diabetic nephropathy is the most common cause of end-stage kidney disease,[7][16] which may require hemodialysis or even kidney transplantation.[17] It is associated with an increased risk of death in general, particularly from cardiovascular disease.[7][18]

Epidemiology

In the U.S., diabetic nephropathy affected an estimated 6.9 million people during 2005–2008.[19] The number of people with diabetes and consequently diabetic nephropathy is expected to rise substantially by the year 2050.[20]

See also

References

- ↑ Kittell F (2012). "Diabetes Management". In Thomas LK, Othersen JB. Nutrition Therapy for Chronic Kidney Disease. CRC Press. p. 198.

- ↑ "diabetic nephropathy". Retrieved 2015-06-27.

- ↑ Longo et al., Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 18th ed., p.2982

- 1 2 3 4 "Diabetes and kidney disease: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". www.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2015-06-27.

- ↑ "Diabetic Nephropathy: Background, Pathophysiology, Etiology". 2015-06-20.

- ↑ Cao, Zemin; Cooper, Mark E (2011). "Pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy". Journal of Diabetes Investigation 2 (4): 243–247. doi:10.1111/j.2040-1124.2011.00131.x. ISSN 2040-1116. PMC 4014960. PMID 24843491.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mora-Fernández C, Domínguez-Pimentel V, de Fuentes MM, et al. (2014). "Diabetic kidney disease: from physiology to therapeutics". J. Physiol. (Lond.) 592 (Pt 18): 3997–4012. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2014.272328. PMID 24907306.

- ↑ Fink, Howard A.; Ishani, Areef; Taylor, Brent C.; Greer, Nancy L.; MacDonald, Roderick; Rossini, Dominic; Sadiq, Sameea; Lankireddy, Srilakshmi; Kane, Robert L. (2012). "Introduction".

- 1 2 Lewis G, Maxwell AP (2014). "Risk factor control is key in diabetic nephropathy". Practitioner 258 (1768): 13–7, 2. PMID 24689163.

- ↑ "CDC - Chronic Kidney Disease - Glossary". Retrieved 2015-07-02.

- ↑ Koroshi, A (2007). "Microalbuminuria, is it so important?". Hippokratia 11 (3): 105–107. ISSN 1108-4189. PMC 2658722. PMID 19582202.

- ↑ "Glomerular filtration rate: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". www.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2015-07-02.

- ↑ Lim, Andy KH (2014). "Diabetic nephropathy – complications and treatment". International Journal of Nephrology and Renovascular Disease 7: 361–381. doi:10.2147/IJNRD.S40172. ISSN 1178-7058. PMC 4206379. PMID 25342915.

- ↑ "Diabetic Nephropathy Treatment & Management: Approach Considerations, Glycemic Control, Management of Hypertension". 2015-06-20.

- ↑ Shlipak, Michael. "Clinical Evidence Handbook: Diabetic Nephropathy: Preventing Progression - American Family Physician". www.aafp.org. Retrieved 2015-06-27.

- ↑ Ding Y, Choi ME (January 2015). "Autophagy in diabetic nephropathy". J Endocrinol 224 (1): R15–30. doi:10.1530/JOE-14-0437. PMC 4238413. PMID 25349246.

- ↑ Lizicarova D, Krahulec B, Hirnerova E, Gaspar L, Celecova Z (2014). "Risk factors in diabetic nephropathy progression at present". Bratisl Lek Listy 115 (8): 517–21. doi:10.4149/BLL_2014_101. PMID 25246291.

- ↑ Pálsson R, Patel UD (2014). "Cardiovascular complications of diabetic kidney disease". Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 21 (3): 273–80. doi:10.1053/j.ackd.2014.03.003. PMC 4045477. PMID 24780455.

- ↑ Lerma, Edgar V. (2014-01-01). Diabetes and Kidney Disease. Springer. ISBN 9781493907939.

- ↑ Lai, K. N.; Tang, S. C. W. (2011-06-08). Diabetes and the Kidney. Karger Medical and Scientific Publishers. ISBN 9783805597432.

Further reading

- "Effects of renin-angiotensin system blockers on renal outcomes and all-cause mortality in patients with diabetic nephropathy: an updated meta-analysis". www.crd.york.ac.uk. Retrieved 2015-07-02.

- Gross, Jorge L.; Azevedo, Mirela J. de; Silveiro, Sandra P.; Canani, Luís Henrique; Caramori, Maria Luiza; Zelmanovitz, Themis (2005). "Diabetic Nephropathy: Diagnosis, Prevention, and Treatment". Diabetes Care 28 (1): 164–176. doi:10.2337/diacare.28.1.164. ISSN 0149-5992. PMID 15616252.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

|