Descartes' theorem

In geometry, Descartes' theorem states that for every four kissing, or mutually tangent, circles, the radii of the circles satisfy a certain quadratic equation. By solving this equation, one can construct a fourth circle tangent to three given, mutually tangent circles. The theorem is named after René Descartes, who stated it in 1643.

History

Geometrical problems involving tangent circles have been pondered for millennia. In ancient Greece of the third century BC, Apollonius of Perga devoted an entire book to the topic.

René Descartes discussed the problem briefly in 1643, in a letter to Princess Elisabeth of the Palatinate. He came up with essentially the same solution as given in equation (1) below, and thus attached his name to the theorem.

Frederick Soddy rediscovered the equation in 1936. The kissing circles in this problem are sometimes known as Soddy circles, perhaps because Soddy chose to publish his version of the theorem in the form of a poem titled The Kiss Precise, which was printed in Nature (June 20, 1936). Soddy also extended the theorem to spheres; Thorold Gosset extended the theorem to arbitrary dimensions.

Definition of curvature

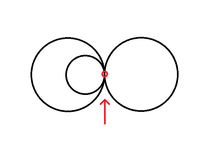

Descartes' theorem is most easily stated in terms of the circles' curvatures. The curvature (or bend) of a circle is defined as k = ±1/r, where r is its radius. The larger a circle, the smaller is the magnitude of its curvature, and vice versa.

The plus sign in k = ±1/r applies to a circle that is externally tangent to the other circles, like the three black circles in the image. For an internally tangent circle like the big red circle, that circumscribes the other circles, the minus sign applies.

If a straight line is considered a degenerate circle with zero curvature (and thus infinite radius), Descartes' theorem also applies to a line and two circles that are all three mutually tangent, giving the radius of a third circle tangent to the other two circles and the line.

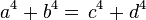

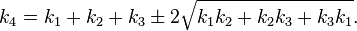

If four circles are tangent to each other at six distinct points, and the circles have curvatures ki (for i = 1, ..., 4), Descartes' theorem says:

-

(1)

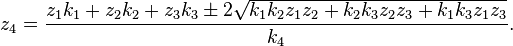

When trying to find the radius of a fourth circle tangent to three given kissing circles, the equation is best rewritten as:

-

(2)

The ± sign reflects the fact that there are in general two solutions. Ignoring the degenerate case of a straight line, one solution is positive and the other is either positive or negative; if negative, it represents a circle that circumscribes the first three (as shown in the diagram above).

Other criteria may favor one solution over the other in any given problem.

Special cases

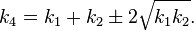

If one of the three circles is replaced by a straight line, then one ki, say k3, is zero and drops out of equation (1). Equation (2) then becomes much simpler:

-

(3)

If two circles are replaced by lines, the tangency between the two replaced circles becomes a parallelism between their two replacement lines. For all four curves to remain mutually tangent, the other two circles must be congruent. In this case, with k2 = k3 = 0, equation (2) is reduced to the trivial

It is not possible to replace three circles by lines, as it is not possible for three lines and one circle to be mutually tangent. Descartes' theorem does not apply when all four circles are tangent to each other at the same point.

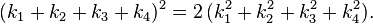

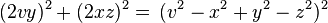

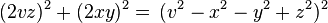

Another special case is when the ki are squares,

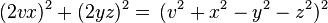

Euler showed that this is equivalent to the simultaneous triplet of Pythagorean triples,

and can be given a parametric solution. When the minus sign of a curvature is chosen,

this can be solved[1] as,

where,

parametric solutions of which are well-known.

Complex Descartes theorem

To determine a circle completely, not only its radius (or curvature), but also its center must be known. The relevant equation is expressed most clearly if the coordinates (x, y) are interpreted as a complex number z = x + iy. The equation then looks similar to Descartes' theorem and is therefore called the complex Descartes theorem.

Given four circles with curvatures ki and centers zi (for i = 1...4), the following equality holds in addition to equation (1):

-

(4)

Once k4 has been found using equation (2), one may proceed to calculate z4 by rewriting equation (4) to a form similar to equation (2):

Again, in general, there are two solutions for z4, corresponding to the two solutions for k4.

Generalizations

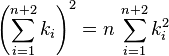

The generalization to n dimensions is sometimes referred to as the Soddy–Gosset theorem, even though it was shown by R. Lachlan in 1886. In n-dimensional Euclidean space, the maximum number of mutually tangent (n − 1)-spheres is n + 2. For example, in 3-dimensional space, five spheres can be mutually tangent.The curvatures of the hyperspheres satisfy

with the case ki = 0 corresponding to a flat hyperplane, in exact analogy to the 2-dimensional version of the theorem.

Although there is no 3-dimensional analogue of the complex numbers, the relationship between the positions of the centers can be re-expressed as a matrix equation, which also generalizes to n dimensions.[2]

See also

Notes

- ↑ A Collection of Algebraic Identities: Sums of Three or More 4th Powers

- ↑ Jeffrey C. Lagarias, Colin L. Mallows, Allan R. Wilks (April 2002). "Beyond the Descartes Circle Theorem". The American Mathematical Monthly 109 (4): 338–361. doi:10.2307/2695498. JSTOR 2695498.

External links

- Interactive applet demonstrating four mutually tangent circles at cut-the-knot

- The Kiss Precise

- XScreenSaver: Screenshots :: An XScreenSaver display hack visualizes Descartes’ theorem, in hack “Apollonian”.

- Jeffrey C. Lagarias, Colin L. Mallows, Allan R. Wilks: Beyond The Descartes Circle Theorem

![[v, x, y, z] =\, [2(ab-cd)(ab+cd), (a^2+b^2+c^2+d^2)(a^2-b^2+c^2-d^2), 2(ac-bd)(a^2+c^2), 2(ac-bd)(b^2+d^2)]](../I/m/3849928e47ad9da1d3c3159f54ee84cc.png)