Commutator subgroup

In mathematics, more specifically in abstract algebra, the commutator subgroup or derived subgroup of a group is the subgroup generated by all the commutators of the group.[1][2]

The commutator subgroup is important because it is the smallest normal subgroup such that the quotient group of the original group by this subgroup is abelian. In other words, G/N is abelian if and only if N contains the commutator subgroup. So in some sense it provides a measure of how far the group is from being abelian; the larger the commutator subgroup is, the "less abelian" the group is.

Commutators

For elements g and h of a group G, the commutator of g and h is ![[g,h] = g^{-1}h^{-1}gh](../I/m/e7488e0d28fa4915d122996a32898885.png) (or

(or ![[g,h] = ghg^{-1}h^{-1}](../I/m/6148765b0fe5cd19ba60f548ec088f06.png) ). The commutator

). The commutator ![[g,h]](../I/m/96c5245a708de7bd96289e21b83f0bcf.png) is equal to the identity element e if and only if

is equal to the identity element e if and only if  , that is, if and only if g and h commute. In general,

, that is, if and only if g and h commute. In general, ![gh = hg[g,h]](../I/m/637822cde50cfce57b2aba9af329db72.png) .

.

An element of G which is of the form ![[g,h]](../I/m/96c5245a708de7bd96289e21b83f0bcf.png) for some g and h is called a commutator. The identity element e = [e,e] is always a commutator, and it is the only commutator if and only if G is abelian.

for some g and h is called a commutator. The identity element e = [e,e] is always a commutator, and it is the only commutator if and only if G is abelian.

Here are some simple but useful commutator identities, true for any elements s, g, h of a group G:

-

![[g,h]^{-1} = [h,g].](../I/m/9d93358824e4ec75724da5a5f43f5276.png)

-

![[g,h]^s = [g^s,h^s]](../I/m/7003394959bd7fb47893548c2772fac3.png) , where

, where  , the conjugate of

, the conjugate of  by

by  .

. - For any homomorphism

,

, ![f([g, h]) = [f(g), f(h)]](../I/m/6c77160d2a46cd05fea22ab174b71b1e.png) .

.

The first and second identities imply that the set of commutators in G is closed under inversion and conjugation. If in the third identity we take H = G, we get that the set of commutators is stable under any endomorphism of G. This is in fact a generalization of the second identity, since we can take f to be the conjugation automorphism on G,  , to get the second identity.

, to get the second identity.

However, the product of two or more commutators need not be a commutator. A generic example is [a,b][c,d] in the free group on a,b,c,d. It is known that the least order of a finite group for which there exists two commutators whose product is not a commutator is 96; in fact there are two nonisomorphic groups of order 96 with this property.[3]

Definition

This motivates the definition of the commutator subgroup ![[G, G]](../I/m/3977a81444c9d8799fad00e62a3b3f78.png) (also called the derived subgroup, and denoted

(also called the derived subgroup, and denoted  or

or  ) of G: it is the subgroup generated by all the commutators.

) of G: it is the subgroup generated by all the commutators.

It follows from the properties of commutators that any element of ![[G, G]](../I/m/3977a81444c9d8799fad00e62a3b3f78.png) is of the form

is of the form

for some natural number  , where the gi and hi are elements of G. Moreover, since

, where the gi and hi are elements of G. Moreover, since ![([g_1,h_1] \cdots [g_n,h_n])^s = [g_1^s,h_1^s] \cdots [g_n^s,h_n^s]](../I/m/0652b66a5762d9b5817484071892fd9b.png) , the commutator subgroup is normal in G. For any homomorphism f: G → H,

, the commutator subgroup is normal in G. For any homomorphism f: G → H,

![f([g_1,h_1] \cdots [g_n,h_n]) = [f(g_1),f(h_1)] \cdots [f(g_n),f(h_n)]](../I/m/a365ee7f024bac07577b72a035896cd1.png) ,

,

so that ![f([G,G]) \leq [H,H]](../I/m/25c2d8bb0d9eaab0ee8bdc8f137214b3.png) .

.

This shows that the commutator subgroup can be viewed as a functor on the category of groups, some implications of which are explored below. Moreover, taking G = H it shows that the commutator subgroup is stable under every endomorphism of G: that is, [G,G] is a fully characteristic subgroup of G, a property which is considerably stronger than normality.

The commutator subgroup can also be defined as the set of elements g of the group which have an expression as a product g = g1 g2 ... gk that can be rearranged to give the identity.

Derived series

This construction can be iterated:

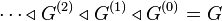

The groups  are called the second derived subgroup, third derived subgroup, and so forth, and the descending normal series

are called the second derived subgroup, third derived subgroup, and so forth, and the descending normal series

is called the derived series. This should not be confused with the lower central series, whose terms are ![G_n := [G_{n-1},G]](../I/m/4aaa6338417983b9960834331206c319.png) .

.

For a finite group, the derived series terminates in a perfect group, which may or may not be trivial. For an infinite group, the derived series need not terminate at a finite stage, and one can continue it to infinite ordinal numbers via transfinite recursion, thereby obtaining the transfinite derived series, which eventually terminates at the perfect core of the group.

Abelianization

Given a group  , a quotient group

, a quotient group  is abelian if and only if

is abelian if and only if ![[G, G]\leq N](../I/m/962157a010b6a303cb937a5ff27c1c5e.png) .

.

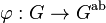

The quotient ![G/[G, G]](../I/m/720bf7cf204847f2a7bf4bfaf2a62c7e.png) is an abelian group called the abelianization of

is an abelian group called the abelianization of  or

or  made abelian.[4] It is usually denoted by

made abelian.[4] It is usually denoted by  or

or  .

.

There is a useful categorical interpretation of the map  . Namely

. Namely  is universal for homomorphisms from

is universal for homomorphisms from  to an abelian group

to an abelian group  : for any abelian group

: for any abelian group  and homomorphism of groups

and homomorphism of groups  there exists a unique homomorphism

there exists a unique homomorphism  such that

such that  . As usual for objects defined by universal mapping properties, this shows the uniqueness of the abelianization Gab up to canonical isomorphism, whereas the explicit construction

. As usual for objects defined by universal mapping properties, this shows the uniqueness of the abelianization Gab up to canonical isomorphism, whereas the explicit construction ![G\to G/[G, G]](../I/m/eef4d9cf5d4fc8120275b4cc8b30510c.png) shows existence.

shows existence.

The abelianization functor is the left adjoint of the inclusion functor from the category of abelian groups to the category of groups. The existence of the abelianization functor Grp → Ab makes the category Ab a reflective subcategory of the category of groups, defined as a full subcategory whose inclusion functor has a left adjoint.

Another important interpretation of  is as

is as  , the first homology group of

, the first homology group of  with integral coefficients.

with integral coefficients.

Classes of groups

A group G is an abelian group if and only if the derived group is trivial: [G,G] = {e}. Equivalently, if and only if the group equals its abelianization. See above for the definition of a group's abelianization.

A group G is a perfect group if and only if the derived group equals the group itself: [G,G] = G. Equivalently, if and only if the abelianization of the group is trivial. This is "opposite" to abelian.

A group with  for some n in N is called a solvable group; this is weaker than abelian, which is the case n = 1.

for some n in N is called a solvable group; this is weaker than abelian, which is the case n = 1.

A group with  for all n in N is called a non solvable group.

for all n in N is called a non solvable group.

A group with  for some ordinal number, possibly infinite, is called a hypoabelian group; this is weaker than solvable, which is the case α is finite (a natural number).

for some ordinal number, possibly infinite, is called a hypoabelian group; this is weaker than solvable, which is the case α is finite (a natural number).

Examples

- The commutator subgroup of the alternating group A4 is the Klein four group.

- The commutator subgroup of the symmetric group Sn is the alternating group An.

- The commutator subgroup of the quaternion group Q = {1, −1, i, −i, j, −j, k, −k} is [Q,Q]={1, −1}.

- The commutator subgroup of the fundamental group π1(X) of a path-connected topological space X is the kernel of the natural homomorphism onto the first singular homology group H1(X).

Map from Out

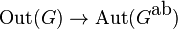

Since the derived subgroup is characteristic, any automorphism of G induces an automorphism of the abelianization. Since the abelianization is abelian, inner automorphisms act trivially, hence this yields a map

See also

- solvable group

- nilpotent group

- The abelianization H/H' of a subgroup H < G of finite index (G:H) is the target of the Artin transfer T(G,H).

Notes

References

- Dummit, David S.; Foote, Richard M. (2004), Abstract Algebra (3rd ed.), John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 0-471-43334-9

- Fraleigh, John B. (1976), A First Course In Abstract Algebra (2nd ed.), Reading: Addison-Wesley, ISBN 0-201-01984-1

- Lang, Serge (2002), Algebra, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 0-387-95385-X

- Suárez-Alvarez, Mariano. "Derived Subgroups and Commutators".

External links

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Commutator subgroup", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

![[g_1,h_1] \cdots [g_n,h_n]](../I/m/714236dd913b30bc446582c6a0de304c.png)

![G^{(n)} := [G^{(n-1)},G^{(n-1)}] \quad n \in \mathbf{N}](../I/m/3d4025c44c23b8ce8360f131c6428e8f.png)