Delirium tremens

| Delirium tremens | |

|---|---|

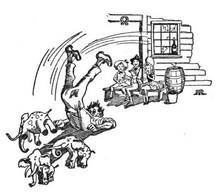

An alcoholic man with delirium tremens on his deathbed, surrounded by his terrified family. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

| ICD-10 | F10.4 |

| ICD-9-CM | 291.0 |

| DiseasesDB | 3543 |

| MedlinePlus | 000766 |

| eMedicine | med/524 |

| MeSH | D000430 |

Delirium tremens (DTs) is a rapid onset of confusion usually caused by withdrawal from alcohol. When it occurs, it is often three days into the withdrawal symptoms and lasts for two to three days. People may also see or hear things other people do not.[1] Physical effects may include shaking, shivering, irregular heart rate, and sweating.[2] Occasionally, a very high body temperature or seizures may result in death.[1] Alcohol is one of the most dangerous drugs to withdraw from.[3]

Delirium tremens typically only occurs in people with a high intake of alcohol for more than a month.[4] A similar syndrome may occur with benzodiazepine and barbiturate withdrawal.[5] Withdrawal from stimulants such as cocaine does not have major medical complications.[6] In a person with delirium tremens it is important to rule out other associated problems such as electrolyte abnormalities, pancreatitis, and alcoholic hepatitis.[1]

Prevention is by treating withdrawal symptoms. If delirium tremens occurs, aggressive treatment improves outcomes. Treatment in a quiet intensive care unit with sufficient light is often recommended. Benzodiazepines are the medication of choice with diazepam, lorazepam, chlordiazepoxide, and oxazepam all commonly used.[4] They should be given until a person is lightly sleeping. The antipsychotic haloperidol may also be used. The vitamin thiamine is recommended.[1] Mortality without treatment is between 15% and 40%.[7] Currently death occurs in about 1% to 4% of cases.[1]

About half of people with alcoholism will develop withdrawal symptoms upon reducing their use. Of these, three to five percent develop DTs or have seizures.[1] The name delirium tremens was first used in 1813; however, the symptoms were well described since the 1700s.[4] The word "delirium" is Latin for "going off the furrow," a plowing metaphor. It is also called shaking frenzy and Saunders-Sutton syndrome.[7] Nicknames include barrel-fever, blue horrors, bottleache, bats, drunken horrors, elephants, gallon distemper, quart mania, pink spiders, among others.[8]

Signs and symptoms

The main symptoms of delirium tremens are nightmares, agitation, global confusion, disorientation, visual and[9] auditory hallucinations, tactile hallucinations, fever, high blood pressure, heavy sweating, and other signs of autonomic hyperactivity (fast heart rate and high blood pressure). These symptoms may appear suddenly, but typically develop two to three days after the stopping of heavy drinking, being worst on the fourth or fifth day.[10] Also, these "symptoms are characteristically worse at night".[11] In general, DT is considered the most severe manifestation of alcohol withdrawal and occurs 3–10 days following the last drink.[9] Other common symptoms include intense perceptual disturbance such as visions of insects, snakes, or rats. These may be hallucinations, or illusions related to the environment, e.g., patterns on the wallpaper or in the peripheral vision that the patient falsely perceives as a resemblance to the morphology of an insect, and are also associated with tactile hallucinations such as sensations of something crawling on the subject—a phenomenon known as formication. Delirium tremens usually includes extremely intense feelings of "impending doom". Severe anxiety and feelings of imminent death are common DT symptoms.

DT can sometimes be associated with severe, uncontrollable tremors of the extremities and secondary symptoms such as anxiety, panic attacks and paranoia. Confusion is often noticeable to onlookers as those with DT will have trouble forming simple sentences or making basic logical calculations. In many cases, people who rarely speak out of turn will have an increased tendency for gaffes even though they are sober.

DT should be distinguished from alcoholic hallucinosis, the latter of which occurs in approximately 20% of hospitalized alcoholics and does not carry a significant mortality. In contrast, DT occurs in 5–10% of alcoholics and carries up to 15% mortality with treatment and up to 35% mortality without treatment.[12] DT is characterized by the presence of altered sensorium; that is, a complete hallucination without any recognition of the real world. DT has extreme autonomic hyperactivity (high pulse, blood pressure, and rate of breathing), and 35-60% of patients have a fever. Some patients experience seizures.

Causes

Delirium tremens is mainly caused by a long period of drinking being stopped abruptly. Withdrawal leads to a biochemical regulation cascade. It may also be triggered by head injury, infection, or illness in people with a history of heavy use of alcohol.

Another cause of delirium tremens is abrupt stopping of tranquilizer drugs of the barbiturate or benzodiazepine classes in a person with a relatively strong addiction to them. Because these tranquilizers' primary pharmacological and physiological effects stem from their manipulation of the GABA chemical and transmitter somatic system, the same neurotransmitter system affected by alcohol, delirium tremens can occur upon abrupt decrease of dosage in those who are heavily dependent. These DTs are much the same as those caused by alcohol and so is the attendant withdrawal syndrome of which they are a manifestation. That is the primary reason benzodiazepines are such an effective treatment for DTs, despite also being the cause of them in many cases. Because ethanol and tranquilizers such as barbiturates and benzodiazepines function as positive allosteric modulators at GABAA receptors, the brain, in its desire to equalize an unbalanced chemical system, triggers the abrupt stopping of the production of endogenous GABA. This decrease becomes more and more marked as the addiction becomes stronger and as higher doses are needed to cause intoxication. In addition to having sedative properties, GABA is an immensely important regulatory neurotransmitter that controls the heart rate, blood pressure, and seizure threshold among myriad other important autonomic nervous subsystems.

Delirium tremens is most common in people who have a history of alcohol withdrawal, especially in those who drink the equivalent of 7 to 8 US pints (3 to 4 l) of beer or 1 US pint (0.5 l) of distilled beverage daily. Delirium tremens also commonly affects those with a history of habitual alcohol use or alcoholism that has existed for more than 10 years.[13]

The exact pharmacology of ethanol is not fully understood; however, it is theorized that delirium tremens is caused by the effect of alcohol on GABA receptors. Constant consumption of alcoholic beverages (and the consequent chronic sedation) causes a counterregulatory response in the brain in an attempt to regain homeostasis.

This causes downregulation of these receptors, as well as an up-regulation in the production of excitatory neurotransmitters, primarily glutamate, and also such as norepinephrine, dopamine, epinephrine, and serotonin, all of which further the drinker's tolerance to alcohol. When alcohol is no longer consumed, these down-regulated GABAA receptor complexes are so insensitive to GABA that the typical amount of GABA produced has little effect; compounded with the fact that GABA normally inhibits action potential formation, there are not as many receptors for GABA to bind to, meaning that sympathetic activation is unopposed. This is also known as an "adrenergic storm", the effects of which can include (but are not limited to) tachycardia, hypertension, fever, night sweats, hyperreflexia, excessive sweating, heart attack, cardiac arrhythmia, stroke, anxiety, panic attacks, paranoia, and agitation.

This is all made worse by excitatory neurotransmitter up-regulation, so not only is sympathetic nervous system over-activity unopposed by GABA, there is also more of the serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine, epinephrine, and particularly glutamate. Excitory NMDA receptors are also up-regulated, contributing to the delirium and neurotoxicity (by excitotoxicity) of withdrawal. Direct measurements of central norepinephrine and its metabolites are in direct correlation to the severity of the alcohol withdrawal syndrome.[14] It is possible that psychological (i.e., non-physical) factors also play a role, in addition to other factors such as infections, malnutrition, or other underlying medical disorders, often related to alcoholism.

Treatment

Delirium tremens due to alcohol withdrawal can be treated with benzodiazepines. High doses may be necessary to prevent death.[15] Pharmacotherapy is symptomatic and supportive. Typically the person is kept sedated with benzodiazepines, such as diazepam, lorazepam, chlordiazepoxide, or oxazepam. In some cases antipsychotics, such as haloperidol may also be used. Older drugs such as paraldehyde and clomethiazole were formerly the traditional treatment but have now largely been superseded by the benzodiazepines.

Acamprosate is occasionally used in addition to other treatments, and is then carried on into long term use to reduce the risk of relapse. If status epilepticus occurs it is treated in the usual way. It can also be helpful to control environmental stimuli, by providing a well-lit but relaxing environment for minimizing distress and visual hallucinations.

Alcoholic beverages can also be prescribed as a treatment for delirium tremens,[16] but this practice is not universally supported.[17]

Society and culture

Nicknames include "the horrors", "the shakes", "the bottleache", "quart mania", "ork orks", "gallon distemper", "the zoots", "barrel fever", "the 750 itch", "pint paralysis", seeing pink elephants. Another nickname is "the Brooklyn Boys" found in Eugene O'Neill's one-act play Hughie set In 1920's Times Square.[18]

Writer Jack Kerouac details his experiences with delirium tremens in his book Big Sur.[19]

One of the characters in Joseph Conrad's novel Lord Jim experiences "DTs of the worst kind" with symptoms that include seeing millions of pink frogs.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Schuckit, MA (27 November 2014). "Recognition and management of withdrawal delirium (delirium tremens).". The New England Journal of Medicine 371 (22): 2109–13. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1407298. PMID 25427113.

- ↑ Healy, David (3 December 2008). Psychiatric Drugs Explained. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 237. ISBN 978-0-7020-2997-4.

- ↑ Fisher, Gary L. (2009). Encyclopedia of substance abuse prevention, treatment, & recovery. Los Angeles: SAGE. p. 1005. ISBN 9781452266015.

- 1 2 3 Stern, TA; Gross, AF; Stern, TW; Nejad, SH; Maldonado, JR (2010). "Current approaches to the recognition and treatment of alcohol withdrawal and delirium tremens: "old wine in new bottles" or "new wine in old bottles".". Primary care companion to the Journal of clinical psychiatry 12 (3). doi:10.4088/PCC.10r00991ecr. PMID 20944765.

- ↑ Posner, Jerome B. (2007). Plum and Posner's Diagnosis of Stupor and Coma. (4 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press, USA. p. 283. ISBN 9780198043362.

- ↑ Galanter, Marc; Kleber, Herbert D (1 July 2008). The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Substance Abuse Treatment (4th ed.). United States of America: American Psychiatric Publishing Inc. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-58562-276-4.

- 1 2 Blom, Jan Dirk (2010). A dictionary of hallucinations (. ed.). New York: Springer. p. 136. ISBN 9781441912237.

- ↑ Baldwin, Dan (2002). Just the FAQ's, Please, About Alcohol and Drug Abuse: Frequently Asked Questions from Families. America Star Books. pp. Chapter four. ISBN 9781611028706.

- 1 2 Delirium Tremens (DTs)~clinical at eMedicine

- ↑ Hales, R.; Yudofsky, S.; Talbott, J. (1999). Textbook of Psychiatry (3rd ed.). London: The American Psychiatric Press.

- ↑ Gelder et al, 2005 p188 Psychiatry 3rd Ed. oxford: New York.

- ↑ Delirium Tremens (DTs): Prognosis at eMedicine

- ↑ MedlinePlus Encyclopedia Delirium Tremens

- ↑ Linnoila, Markku (Fall 1989). "Alcohol withdrawal syndrome and sympathetic nervous system function — Biological Research at National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism". Alcohol Health & Research World.

- ↑ Wolf KM, Shaughnessy AF, Middleton DB (1993). "Prolonged delirium tremens requiring massive doses of medication". J Am Board Fam Pract 6 (5): 502–4. PMID 8213241.

- ↑ Rosenbaum M, McCarty T (2002). "Alcohol prescription by surgeons in the prevention and treatment of delirium tremens: Historic and current practice". General hospital psychiatry 24 (4): 257–259. doi:10.1016/S0163-8343(02)00188-3. PMID 12100836.

- ↑ Sattar SP, Qadri SF, Warsi MK, Okoye C, Din AU, Padala PR, Bhatia SC (2006). "Use of alcoholic beverages in VA medical centers". Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy 1: 30. doi:10.1186/1747-597X-1-30. PMC 1624810. PMID 17052353.

- ↑ Paulson, Michael, "Gambling on O’Neill: Forest Whitaker Makes His Broadway Debut in ‘Hughie’", New York Times, February 3, 2016. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- ↑ Summary and analysis of novel

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||