Robert Delaunay

| Robert Delaunay | |

|---|---|

%2C_40_x_46_cm%2C_Kunsthalle_Hamburg.jpg) Simultaneous Windows on the City, 1912, Hamburger Kunsthalle | |

| Born |

Robert-Victor-Felix Delaunay 12 April 1885 Paris, France |

| Died |

25 October 1941 (aged 56) Montpellier, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Known for | Painting |

| Movement | Divisionism, Cubism, Orphism, Abstract art |

Robert Delaunay (12 April 1885 – 25 October 1941) was a French artist who, with his wife Sonia Delaunay and others, cofounded the Orphism art movement, noted for its use of strong colours and geometric shapes. His later works were more abstract, reminiscent of Paul Klee. His key influence related to bold use of colour and a clear love of experimentation with both depth and tone.

Biography

Early life

Robert Delaunay was born in Paris, the son of George Delaunay and Countess Berthe Félicie de Rose. While he was a child, Delaunay's parents divorced, and he was raised by his mother's sister Marie and her husband Charles Damour, in La Ronchère near Bourges. When he failed his final exam and said he wanted to become a painter, his uncle in 1902 sent him to Ronsin's atelier to study Decorative Arts in the Belleville district of Paris.[1] At age 19, he left Ronsin to focus entirely on painting and contributed six works to the Salon des Indépendants in 1904.[2]

He traveled to Brittany, where he was influenced by the group of Pont-Aven; and, in 1906, he contributed works he painted in Brittany to the 22nd Salon des Indépendants, where he met Henri Rousseau.[2]

Delaunay formed a close friendship at this time with Jean Metzinger, with whom he shared an exhibition at a gallery run by Berthe Weill early in 1907. The two of them were singled out by the art critic Louis Vauxcelles in 1907 as Divisionists who used large, mosaic-like 'cubes' to construct small but highly symbolic compositions.[3]

Robert Herbert writes: "Metzinger's Neo-Impressionist period was somewhat longer than that of his close friend Delaunay... The height of his Neo-Impressionist work was in 1906 and 1907, when he and Delaunay did portraits of each other (Art market, London, and Museum of Fine Arts, Houston) in prominent rectangles of pigment. (In the sky of Coucher de soleil no. 1, 1906–07, Collection Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, is the solar disk which Delaunay was later to make into a personal emblem)."[4] Herbert describes the vibrating image of the sun in Metzinger's painting, and so too of Delaunay's Paysage au disque (1906–07), as "an homage to the decomposition of spectral light that lay at the heart of Neo-Impressionist color theory..."[5]

Metzinger, followed closely by Delaunay—the two often painting together in 1906 and 1907—would develop a new sub-style of Neo-Impressionism that had great significance shortly thereafter within the context of their Cubist works. Piet Mondrian developed a similar mosaic-like Divisionist technique circa 1909. The Futurists later (1909–1916) would incorporate the style, under the influence of Gino Severini's Parisian works (from 1907 onward), into their dynamic paintings and sculpture.[4]

Towards abstraction (1908–1913)

At the prime of his career he painted the known series that included: the Saint-Sévrin series (1909–10); the City series (1909–11); the Eiffel Tower series (1909–12); the City of Paris series (1911–12); the Window series (1912–14); the Cardiff Team series (1913); the Circular Forms series (1913); and The First Disk (1913).

Delaunay is most closely identified with Orphism. From 1912 to 1914, he painted nonfigurative paintings based on the optical characteristics of brilliant colors that were so dynamic they would function as the form. His theories are mostly concerned with color and light and influenced many including Stanton Macdonald-Wright, Morgan Russell, Patrick Henry Bruce, Der Blaue Reiter, August Macke, Franz Marc, Paul Klee, and Lyonel Feininger. Apollinaire was strongly influenced by Delaunay’s theories of color and often quoted from them to explain Orphism. Delaunay’s fixations with color as the expressive and structural means were sustained with his study of color.

His writings on color, which were influenced by scientists and theoreticians, are intuitive and can be sometimes random statements based on the belief that color is a thing in itself with its own powers of expression and form. He believes painting is a purely visual art that depends on intellectual elements, and perception is in the impact of colored light from the eye. The contrasts and harmonies of color produce in the eye simultaneous movements and correspond to movement in nature. Vision becomes the subject of painting.

His early paintings are deeply rooted in Neoimpressionism. Night Scene for example has vigorous activity with the use of lively brushstrokes in bright colors against a dark background. It doesn’t define solid object but the areas that surround them.

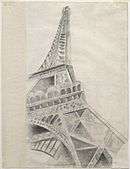

Spectral colors of Neoimpressionism were later abandoned, the Eiffel Tower series, were fragmentation of solid objects and their merging with space was learned. Influences in this series were Cézanne, Analytical Cubism, and Futurism. In the Eiffel Tower the interpenetration of tangible objects and surrounding space is accompanies by intense movement of geometric plans that are more dynamic than static equilibrium of Cubist forms.

In 1908, after a term in the military working as a regimental librarian, he met Sonia Terk; at the time she was married to a German art dealer whom she would soon divorce. In 1909, Delaunay began to paint a series of studies of the city of Paris and the Eiffel Tower. The following year, he married Terk, and the couple settled in a studio apartment in Paris, where their son Charles was born in January 1911. At the invitation of Wassily Kandinsky, Delaunay joined The Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter), a Munich-based group of abstract artists, in 1911, and his art took a turn for the abstract Delaunay was also successful in Germany, Switzerland, and Russia. He participated in the first Blanc Reiter exhibition in Munich and sold four works. Delaunay’s paintings encouraged an enthusiastic response with Blaue Reiter. The Blaue Reiter connections led to Erwin Ritter von Busse’s article “Robert Delaunay’s Methods of Compositions” which appeared in the 1912 Blaue Reiter Almanac. Delaunay would go to exhibit in February of that year, in the second Blaue Reiter exhibition in Munich and Valet de Carrean in Moscow.

“This happened in 1912. Cubism was in full force. I made paintings that seemed like prisms compared to the Cubism my fellow artists were producing. I was the heretic of Cubism. I had great arguments with my comrades who banned color from their palette, depriving it of all elemental mobility. I was accused of returning to Impressionism, of making decorative paintings, etc.… I felt I had almost reached my goal”.[6]

1912 was a turning point for Delaunay. On March 13 his first major exhibition in Paris closed after two weeks at the Galerie Barbazanges. The exhibition showed forty-six works from his early Impressionist works to his Cubist Eiffel Tower painting from 1909–1911. Art Critic Guillaume Apollinaire praised those works of the exhibition and proclaimed Delaunay as “an artist who has a monumental vision of the world.”

In the March 23, 1912, issue of L'Assiette au Beurre, The first published suggestion that Delaunay had broken with this group of Cubists appeared, in James Burkley's review of that year's Salon des Indépendants. Burkley wrote, "The Cubists, who occupy only a room, have multiplied. Their leaders, Picasso and Braque, have not participated in their grouping, and Delaunay, commonly labeled a Cubist, has wished to isolate himself and declare that he has nothing in common with Metzinger or Le Fauconnier.”

With Apollinaire, Delaunay traveled to Berlin in January 1913 for an exhibition of his work at Galerie Der Sturm. On their way back to Paris, the two stayed with August Macke in Bonn, where Macke introduced them to Max Ernst.[7] When his painting La ville de Paris was rejected by the Armory Show as being too big[8] he instructed Samuel Halpert to remove all his works from the show.[2]

Spanish and Portuguese years (1914–1920)

At the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 Sonia and Robert were staying in Fontarabie in Spain. They decided not to return to France and settled in Madrid. In August 1915 they moved to Portugal where they shared a home with Samuel Halpert and Eduardo Viana.[9] With Viana and their friends Amadeo de Souza Cardoso (whom the Delaunays had already met in Paris) and José de Almada Negreiros they discussed an artistic partnership.[2][10] First declared a deserter, Robert was declared unfit for military duty at the French consulate in Vigo on June 13, 1916.[2]

The Russian Revolution brought an end to the financial support Sonia received from her family in Russia, and a different source of income was needed. In 1917 the Delaunays met Sergei Diaghilev in Madrid. Robert designed the stage for his production of Cleopatra (costume design by Sonia Delaunay). Robert Delaunay illustrates Tour Eiffel for Vicente Huidobro.[2]

Paul Poiret refused a business partnership with Sonia in 1920, citing as one of the reasons her marriage to a deserter.[11] The Der Sturm gallery in Berlin showed works by Sonia and Robert from their Portuguese period the same year.[2][12]

Return to Paris and later life (1921–1941)

After the war, in 1921, they returned to Paris. Delaunay continued to work in a mostly abstract style. During the 1937 World Fair in Paris, Delaunay participated in the design of the railway and air travel pavilions. When World War II erupted, the Delaunays moved to the Auvergne, in an effort to avoid the invading German forces. Suffering from cancer, Delaunay was unable to endure being moved around, and his health deteriorated. He died from cancer on 25 October 1941 in Montpellier at the age of 56. His body was reburied in 1952 in Gambais.[2]

Gallery

-

Robert Delaunay, c.1907, Nature morte au vase de fleurs, oil on canvas, 46.4 x 55 cm

-

Robert Delaunay, 1906, Jean Metzinger, oil on paper, 43.2 x 54.9 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

-

Robert Delaunay, 1905–06, Autoportrait, oil on canvas, Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris

-

Robert Delaunay, 1906, Carousel of Pigs, oil on canvas, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

-

_1906.jpg)

Robert Delaunay, 1906, L'homme à la tulipe (Portrait de M. Jean Metzinger), oil on canvas, 72.4 x 48.5 cm (28 1/2 by 19 1/8 in). Exhibited in Paris at the 1906 Salon d'Autome (no. 420) along with a portrait of Delaunay by Metzinger

-

Robert Delaunay, 1907, Portrait of Wilhelm Uhde. Robert Delaunay and Sonia Terk met through the German collector/dealer Wilhelm Uhde, with whom Sonia had been married as she said for "convenience"

-

Robert Delaunay, 1909-10, Saint-Séverin No. 3, oil on canvas, 114.1 × 88.6 cm, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

-

Robert Delaunay, 1910–12, La Ville de Paris, oil on canvas, 267 × 406 cm, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

-

Robert Delaunay, 1911-12, Window on the City No. 3, oil on canvas, 113.7 × 130.8 cm (44.8 × 51.5 in), Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

-

Robert Delaunay, 1912, Windows Open Simultaneously 1st Part, 3rd Motif, oil on canvas, 57 × 123 cm (22.4 × 48.4 in), Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

-

Robert Delaunay, 1913, L'Équipe de Cardiff, Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven

-

Robert Delaunay, 1913, L'Équipe de Cardiff, oil on canvas, 326 × 208 cm, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

-

%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_140_%C3%97_142_cm%2C_Mus%C3%A9e_d'Art_Moderne_de_la_Ville_de_Paris.jpg)

Robert Delaunay, 1915, Nu à la toilette (Nu à la coiffeuse), oil on canvas, 140 × 142 cm, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

-

Robert Delaunay, 1916, Portuguese Woman, oil on canvas, 135.9 × 161 cm, Columbus Museum of Art

-

Robert Delaunay, 1926-28, Eiffel Tower, Conté crayon on paper, 62.3 × 47.5 cm (24.5 × 18.7 in), Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, The Hilla Rebay Collection

-

Robert Delaunay, 1926, Tour Eiffel, oil on canvas, 169 × 86 cm, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

-

Robert Delaunay, 1930, Circular Forms, oil on canvas, 67.3 × 109.8 cm (26.5 × 43.2 in), Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Gift by Andrew Powie Fuller and Geraldine Spreckels Fuller Collection, 1999

-

Robert Delaunay, 1938, Rythme n°1, Decoration for the Salon des Tuileries, oil on canvas, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

Museum collections

Robert Delaunay's works can be found in museums and loaned from private collections around the world:

Europe

The Musée National d'Art Moderne in Paris, the Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin, the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum (Spain), Kunstmuseum Basel (Switzerland), the National Galleries of Scotland, the New Art Gallery (Walsall, England), Palazzo Cavour (Turin, Italy), the Peggy Guggenheim Collection (Venice), National Museum of Serbia, Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, The Netherlands), Palais des Beaux-Arts de Lille (France).

United States

The Albright-Knox Art Gallery (Buffalo, New York), the Art Institute of Chicago, the Columbus Museum of Art, the Berkeley Art Museum, the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center at Vassar College (Poughkeepsie, New York), the Guggenheim Museum (New York City), the Honolulu Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art (New York City), the National Gallery of Art (Washington, D.C.), the Dallas Museum of Art (Dallas, TX), the San Diego Museum of Art, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art

Rest of the world

The National Gallery of Victoria (Australia), the Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art (Japan).

Publications

- Baron, Stanley; Damase, Jacques (1995). Sonia Delaunay: The Life of an Artist. Harry N. Abrahams. ISBN 0-8109-3222-9.

- Düchting, Hajo (1995). Delaunay. Taschen. ISBN 3-8228-9191-6.

- Robert Delaunay – Sonia Delaunay: Das Centre Pompidou zu Gast in Hamburg. Hamburger Kunsthalle. 1999. ISBN 9783770152162.

- Gordon Hughes (1997). Envisioning Abstraction: The Simultaneity Of Robert Delaunay's First Disk.

See also

References

- ↑ Düchting: p7

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Robert Delaunay – Sonia Delaunay, 1999, ISBN 3-7701-5216-6

- ↑ Art of the 20th Century

- 1 2 Robert Herbert, Neo-Impressionism, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York, 1968

- ↑ Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo, Jean Metzinger, Coucher de soleil No. 1

- ↑ Robert Delaunay, First Notebook, 1939, in The New Art of Color: The Writings of Robert and Sonia Delaunay, Viking Press, 1978

- ↑ Willard Bohn: Apollinaire and the international avant-garde (1997), ISBN 0-7914-3195-9, p82

- ↑ La ville de Paris measures 234X294cm.

- ↑ Some sources mention an Eduardo Vianna

- ↑ Düchting: p51

- ↑ Valérie Guillaume: Sonia und Tissus Delaunay. In Robert Delaunay – Sonia Delaunay, 1999, ISBN 3-7701-5216-6, p 31

- ↑ Düchting: p91

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Robert Delaunay. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Robert Delaunay |

- 1913 - "Simultaneous Contrasts: Sun and Moon" by Robert Delaunay on YouTube, Museum of Modern Art, video, 2:00

- Robert Delaunay at the Internet Movie Database

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|