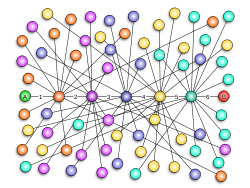

Six degrees of separation

Six degrees of separation is the theory that everyone and everything is six or fewer steps away, by way of introduction, from any other person in the world, so that a chain of "a friend of a friend" statements can be made to connect any two people in a maximum of six steps. It was originally set out by Frigyes Karinthy in 1929 and popularized by a 1990 play written by John Guare.

Early conceptions

Shrinking world

Theories on optimal design of cities, city traffic flows, neighborhoods and demographics were in vogue after World War I. These conjectures were expanded in 1929 by Hungarian author Frigyes Karinthy, who published a volume of short stories titled Everything is Different. One of these pieces was titled "Chains," or "Chain-Links." The story investigated in abstract, conceptual, and fictional terms many of the problems that would captivate future generations of mathematicians, sociologists, and physicists within the field of network theory.[1][2] Due to technological advances in communications and travel, friendship networks could grow larger and span greater distances. In particular, Karinthy believed that the modern world was 'shrinking' due to this ever-increasing connectedness of human beings. He posited that despite great physical distances between the globe's individuals, the growing density of human networks made the actual social distance far smaller.

As a result of this hypothesis, Karinthy's characters believed that any two individuals could be connected through at most five acquaintances. In his story, the characters create a game out of this notion. He writes:

A fascinating game grew out of this discussion. One of us suggested performing the following experiment to prove that the population of the Earth is closer together now than they have ever been before. We should select any person from the 1.5 billion inhabitants of the Earth – anyone, anywhere at all. He bet us that, using no more than five individuals, one of whom is a personal acquaintance, he could contact the selected individual using nothing except the network of personal acquaintances.[3]

This idea both directly and indirectly influenced a great deal of early thought on social networks. Karinthy has been regarded as the originator of the notion of six degrees of separation.[2] A related theory deals with the quality of connections, rather than their existence. The theory of three degrees of influence was created by Nicholas A. Christakis and James H. Fowler.

Small world

Michael Gurevich conducted seminal work in his empirical study of the structure of social networks in his 1961 Massachusetts Institute of Technology PhD dissertation under Ithiel de Sola Pool.[4] Mathematician Manfred Kochen, an Austrian who had been involved in urban design, extrapolated these empirical results in a mathematical manuscript, Contacts and Influences,[5] concluding that in a U.S.-sized population without social structure, "it is practically certain that any two individuals can contact one another by means of at most two intermediaries. In a [socially] structured population it is less likely but still seems probable. And perhaps for the whole world's population, probably only one more bridging individual should be needed." They subsequently constructed Monte Carlo simulations based on Gurevich's data, which recognized that both weak and strong acquaintance links are needed to model social structure. The simulations, carried out on the relatively limited computers of 1973, were nonetheless able to predict that a more realistic three degrees of separation existed across the U.S. population, foreshadowing the findings of American psychologist Stanley Milgram.

Milgram continued Gurevich's experiments in acquaintanceship networks at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S. Kochen and de Sola Pool's manuscript, Contacts and Influences,[6] was conceived while both were working at the University of Paris in the early 1950s, during a time when Milgram visited and collaborated in their research. Their unpublished manuscript circulated among academics for over 20 years before publication in 1978. It formally articulated the mechanics of social networks, and explored the mathematical consequences of these (including the degree of connectedness). The manuscript left many significant questions about networks unresolved, and one of these was the number of degrees of separation in actual social networks. Milgram took up the challenge on his return from Paris, leading to the experiments reported in The Small World Problem [7] in popular science journal Psychology Today, with a more rigorous version of the paper appearing in Sociometry two years later.[8] The Psychology Today article generated enormous publicity for the experiments, which are well known today, long after much of the formative work has been forgotten.

Milgram's article made famous[7] his 1967 set of experiments to investigate de Sola Pool and Kochen's "small world problem." Mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot, born in Warsaw, growing up in Poland then France, was aware of the Statist rule of thumb, and was also a colleague of de Sola Pool, Kochen and Milgram at the University of Paris during the early 1950s (Kochen brought Mandelbrot to work at the Institute for Advanced Study and later IBM in the U.S.). This circle of researchers was fascinated by the interconnectedness and "social capital" of human networks. Milgram's study results showed that people in the United States seemed to be connected by approximately three friendship links, on average, without speculating on global linkages; he never actually used the term "six degrees of separation." Since the Psychology Today article gave the experiments wide publicity, Milgram, Kochen, and Karinthy all had been incorrectly attributed as the origin of the notion of six degrees; the most likely popularizer of the term "six degrees of separation" would be John Guare, who attributed the value 'six' to Marconi.[9]

Continued research: Small World Project

In 2003, Columbia University conducted an analogous experiment on social connectedness amongst Internet email users. Their effort was named the Columbia Small World Project, and included 24,163 e-mail chains, aimed at 18 targets from 13 different countries around the world.[10] Almost 100,000 people registered, but only 384 (0,4%) reached the final target. Amongst the successful chains, while shorter lengths were more common some only reached their target after 7, 8, 9 or 10 steps. Dodds et al. noted that participants (all of whom volunteers) were strongly biased towards existing models of Internet users[Note 1] and that connectedness based on professional ties was much stronger than those within families or friendships. The authors cite "lack of interest" as the predominating factor in the high attrition rate,[Note 2] a finding consistent with earlier studies.[11]

Research

Several studies, such as Milgram's small world experiment, have been conducted to empirically measure this connectedness. The phrase "six degrees of separation" is often used as a synonym for the idea of the "small world" phenomenon.[12]

However, detractors argue that Milgram's experiment did not demonstrate such a link,[13] and the "six degrees" claim has been decried as an "academic urban myth".[11][14] Also, the existence of isolated groups of humans, for example the Korubo and other native Brazilian populations,[15] would tend to invalidate the strictest interpretation of the hypothesis.

Computer networks

In 2001, Duncan Watts, a professor at Columbia University, attempted to recreate Milgram's experiment on the Internet, using an e-mail message as the "package" that needed to be delivered, with 48,000 senders and 19 targets (in 157 countries). Watts found that the average (though not maximum) number of intermediaries was around six.[16] A 2007 study by Jure Leskovec and Eric Horvitz examined a data set of instant messages composed of 30 billion conversations among 240 million people. They found the average path length among Microsoft Messenger users to be 6.[17]

It has been suggested by some commentators[18] that interlocking networks of computer mediated lateral communication could diffuse single messages to all interested users worldwide as per the 6 degrees of separation principle via Information Routing Groups, which are networks specifically designed to exploit this principle and lateral diffusion.

Find Satoshi

The UK-based game company Mind Candy is currently testing the theory by distributing a picture of a Japanese man named Satoshi. The puzzle was originally a part of Mind Candy's Perplex City, but it has since grown into its own project.[19]

An optimal algorithm to calculate degrees of separation in social networks

Bakhshandeh et al.[20] have addressed the search problem of identifying the degree of separation between two users in social networks such as Twitter. They have introduced new search techniques to provide optimal or near optimal solutions. The experiments are performed using Twitter, and they show an improvement of several orders of magnitude over greedy approaches. Their optimal algorithm finds an average degree of separation of 3.43 between two random Twitter users, requiring an average of only 67 requests for information over the Internet to Twitter. A near-optimal solution of length 3.88 can be found by making an average of 13.3 requests.

Popularization

No longer limited strictly to academic or philosophical thinking, the notion of six degrees recently has become influential throughout popular culture. Further advances in communication technology – and particularly the Internet – have drawn great attention to social networks and human interconnectedness. As a result, many popular media sources have addressed the term. The following provide a brief outline of the ways such ideas have shaped popular culture.

Popularization of offline practice

John Guare's Six Degrees of Separation

American playwright John Guare wrote a play in 1990 and later released a film in 1993 that popularized it. It is Guare's most widely known work.

The play ruminates upon the idea that any two individuals are connected by at most five others. As one of the characters states:

I read somewhere that everybody on this planet is separated by only six other people. Six degrees of separation between us and everyone else on this planet. The President of the United States, a gondolier in Venice, just fill in the names. I find it A) extremely comforting that we're so close, and B) like Chinese water torture that we're so close because you have to find the right six people to make the right connection... I am bound to everyone on this planet by a trail of six people.[21]

Guare, in interviews, attributed his awareness of the "six degrees" to Marconi. Although this idea had been circulating in various forms for decades, it is Guare's piece that is most responsible for popularizing the phrase "six degrees of separation." Following Guare's lead, many future television and film sources would later incorporate the notion into their stories.

J. J. Abrams, the executive producer of television series Six Degrees and Lost, played the role of Doug in the film adaptation of this play. Many of the play's themes are apparent in his television shows (see below).

Kevin Bacon game

The game "Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon"[22] was invented as a play on the concept: the goal is to link any actor to Kevin Bacon through no more than six connections, where two actors are connected if they have appeared in a movie or commercial together. It was created by three students at Albright College in Pennsylvania,[23] who came up with the concept while watching Footloose. On September 13, 2012, Google made it possible to search for any given actor's 'Bacon Number' through their search engine.

Upon the arrival of the 4G mobile network in the United Kingdom, Kevin Bacon appears in several commercials for the EE Network in which he links himself to several well known celebrities and TV shows in the UK.

Six Degrees of Der Kommissar

Music critics have fun tracing the history and dissecting the popular song "Der Kommissar" which was first written and recorded by Austrian musician Falco with German vocals in 1981, then passed on and reworked in English by British band After The Fire in 1982, then lyrically rewritten and renamed "Deep In The Dark" by Laura Branigan in 1983 in the U.S., then retitled again to "Don't Turn Around" and rerecorded in a punk rock style by The Squids in 1996 also in the U.S., then passed on to Brazilian rap band Comunidade Nin-Jitsu in 2005 and renamed "Rap Do Trago", then finally back to the U.S. and rerecorded in its traditional style in 2007 by Dale Bozzio, who is the former lead singer of new wave band Missing Persons. In this situation, connections among six such diverse musical expressionists were generated through a song. In the beginning, the composer might never have thought that the song could spread so far. However, the six degree has demonstrated that "the small world" does exist.

John L. Sullivan

An early version involved former world Heavyweight boxing champion, John L. Sullivan, in which people would ask others to "shake the hand that shook the hand that shook the hand that shook the hand of 'the great John L.'"[24]

In popular culture

- Six Degrees of Separation is a 1993 drama film featuring Will Smith, Donald Sutherland, and Stockard Channing.

- Six Degrees is a 2006 television series on ABC in the US. The show details the experiences of six New Yorkers who go about their lives without realizing they are affecting each other, and gradually meet one another.[25]

- The television program Lost also explores the idea of six degrees of separation, as almost all the characters have randomly met each other before the crash or someone the other characters know.

- Lonely Planet Six Degrees is a TV travel show that uses the "six degrees of separation" concept: the hosts, Asha Gill and Toby Amies, explore various cities through its people, by following certain personalities of the city around and being introduced by them to other personalities.

- The Oscar-winning film Babel is based on the concept of Six Degrees of Separation. The lives of all of the characters were intimately intertwined, although they did not know each other and lived thousands of miles from each other.

- Six Degrees of Martina McBride was a television pilot where six aspiring country singers from America's smallest towns try to connect themselves to Martina McBride in under six points of human connection. Those that make it from "Nowhere to Nashville to New York," get a shot at a studio session with Martina McBride and a record deal with SONY BMG.

- The Woestijnvis production Man Bijt Hond, broadcast on Flemish TV, features a weekly section Dossier Costers, in which a worldwide event from the past week is linked to Gustaaf Costers, an ordinary Flemish citizen, in six steps.[26]

- One of the achievements in the video game Brütal Legend is called "Six Degrees of Schafer," after the concept and Tim Schafer, who was presumably in the handful of players to have the achievement as of the game's release. A player can only obtain this achievement by playing online with someone who already has it, further paralleling it to the concept.

- Connected: The Power of Six Degrees is a 2008 television episode on the Science Channel in the US and abroad.[27]

- The No Doubt song "Full Circle" has a central theme dealing with six degrees of separation.

- "Six Degrees of Separation" is an episode of the reimagined Battlestar Galactica series.

- "Six Degrees of Separation" is the 2nd track on The Script's third album, #3.

- "Six Degrees" is the sixth track on Scouting for Girls' album, The Light Between Us.

- The Israeli TV program Cultural Attache, presented by Dov Alfon, is based on the concept of Six Degrees of Separation. The first guest is asked to name a cultural figure with which he has an unexpected connection, and this person is interviewed and gives yet another name as connection, till the 6th person on the show, who is then asked about a possible connection to the first guest. Such connection is found in about 50% of the interviews.[28]

- Six Degrees of Inner Turbulence is a 2002 album by progressive rock band Dream Theater.

- Six Degrees of Everything is a comedy series starring Benny Fine and Rafi Fine where they illustrate that everything in the world is connected by a six-degree separation.[29]

- Jorden runt på 6 steg is a three-episode infotainment series produced by Mexiko Media which aired in Swedish Kanal 5 in 2015. For each episode, hosts Filip Hammar and Fredrik Wikingsson selected one random person (in Bolivia, Nepal and Senegal) and traced their relationships to three respective celebrities: Leif G. W. Persson, Gordon Ramsay and Buzz Aldrin within a week of travelling. They reached Persson within seven steps, and Ramsay and Aldrin within six steps.

Website and application

SixDegrees.org

On January 18, 2007, Kevin Bacon launched SixDegrees.org, a web site that builds on the popularity of the "small world phenomenon" to create a charitable social network and inspire giving to charities online. Bacon started the network with celebrities who are highlighting their favorite charities – including Kyra Sedgwick (Natural Resources Defense Council), Nicole Kidman (UNIFEM), Ashley Judd (YouthAIDS), Bradley Whitford and Jane Kaczmarek (Clothes off Our Back), Dana Delany (Scleroderma Research Foundation), Robert Duvall (Pro Mujer), Rosie O'Donnell (Rosie's For All Kids Foundation), and Jessica Simpson (Operation Smile) – and he encouraged everyone to be celebrities for their own causes by joining the Six Degrees movement.

"SixDegrees.org is about using the idea that we are all connected to accomplish something good," said Bacon. "It is my hope that Six Degrees will soon be something more than a game or a gimmick. It will also be a force for good, by bringing a social conscience to social networking." The game, 'Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon,' made the rounds of college campuses over the past decade and lived on to be a shorthand term for the small world phenomenon.

Bacon created SixDegrees.org in partnership with the nonprofit Network for Good, AOL, and Entertainment Weekly. Through SixDegrees.org, which builds on Network for Good's giving system for donating to more than one million charities online and AOL's AIM Pages social networking service, people can learn about and support the charities of celebrities or fundraise for their own favorite causes with their own friends and families. Bacon will match the charitable dollars raised by the top six non-celebrity fundraisers with grants of up to $10,000 each[30]

A Facebook platform application named "Six Degrees" was developed by Karl Bunyan, which calculates the degrees of separation between different people. It had over 5.8 million users, as seen from the group's page. The average separation for all users of the application is 5.73 degrees, whereas the maximum degree of separation is 12. The application has a "Search for Connections" window to input any name of a Facebook user, to which it then shows the chain of connections. In June 2009, Bunyan shut down the application, presumably due to issues with Facebook's caching policy; specifically, the policy prohibited the storing of friend lists for more than 24 hours, which would have made the application inaccurate.[31] A new version of the application became available at Six Degrees after Karl Bunyan gave permission to a group of developers led by Todd Chaffee to re-develop the application based on Facebook's revised policy on caching data.[32][33]

The initial version of the application was built at a Facebook Developers Garage London hackathon with Mark Zuckerberg in attendance.[34]

Yahoo! Research Small World Experiment has been conducting an experiment and everyone with a Facebook account can take part in it. According to the research page, this research has the potential of resolving the still unresolved theory of six degrees of separation.[22][35]

Facebook's data team released two papers in November 2011 which document that amongst all Facebook users at the time of research (721 million users with 69 billion friendship links) there is an average distance of 4.74.[36] Probabilistic algorithms were applied on statistical metadata to verify the accuracy of the measurements.[37] It was also found that 99.91% of Facebook users were interconnected, forming a large connected component.[38]

| Year | Distance | |

|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 4.28 | |

| 2011 | 3.74 | |

| 2016 | 3.57 | |

| Distances as reported in Feb 2016 [39] | ||

Facebook reported that the distance had decreased to 3.57 in February 2016, when it had 1.6 billion users (about 22% of world population).[39]

The LinkedIn professional networking site operates on the concept of how many steps one is away from a person with which he or she wishes to communicate. On LinkedIn, people in one's network are called connections and the network is made up of 1st-degree, 2nd-degree, and 3rd-degree connections and fellow members of LinkedIn Groups. Using LinkedIn groups can extend users' reaches to other group members, and filling the gaps in users' current network. Once users joined these groups, the best approach is to participate in or start discussions beforehand. This builds credibility and entices folks to agree to connection requests based on the fact that the user has a shared viewpoint and authentic interest in similar subject matters. Another way to link to weak ties is to go through strong ties. To do that effectively, use LinkedIn to search for users' desired place of employment or possible business contact. That search will result in folks who are second, third or even first degree connections that a user should reach out to via users' stronger ties; it’s important to leverage users' stronger ties’ relationships with people out of users' network but within their own. Similarly, one should look beyond their strong ties and reach out to people they are associated with four or five degrees out. Today, social media makes the job of identifying these ties much easier. Indeed, it’s the premise that LinkedIn is built upon. Facebook and LinkedIn not only suggest people you may know through weaker connections, the social platforms also provide information on educational, professional, and personal interests; data essential to constructing tailored introductions and conversations.[40]

SixDegrees.com

SixDegrees.com was an early social-networking website that existed from 1997 to 2001. It allowed users to list friends, family members and acquaintances, send messages and post bulletin board items to people in their first, second, and third degrees, and see their connection to any other user on the site. At its height, it had 3,500,000 fully registered members.[41] However, it was closed in 2000 because the idea was too new for its time. [42]

Users on Twitter can follow other users creating a network. According to a study of 5.2 billion such relationships by social media monitoring firm Sysomos, the average distance on Twitter is 4.67. On average, about 50% of people on Twitter are only four steps away from each other, while nearly everyone is five steps or less away.[43]

In another work, researchers have shown that the average distance of 1,500 random users in Twitter is 3.435. They calculated the distance between each pair of users using all the active users in Twitter.[44]

Mathematics

Mathematicians use an analogous notion of collaboration distance:[45] two persons are linked if they are coauthors of an article. The collaboration distance with mathematician Paul Erdős is called the Erdős number. Erdős-Bacon numbers and Erdős-Bacon-Sabbath (EBS) numbers[46] are further extensions of the same thinking.

Watts and Strogatz showed that the average path length between two nodes in a random network is equal to ln N / ln K, where N = total nodes and K = acquaintances per node. Thus if N = 300,000,000 (90% of the US population) and K = 30 then Degrees of Separation = 19.5 / 3.4 = 5.7 and if N = 6,000,000,000 (90% of the World population) and K = 30 then Degrees of Separation = 22.5 / 3.4 = 6.6. (Assume 10% of population is too young to participate.)

Psychology

A 2007 article published in The Industrial-Organizational Psychologist,[47] by Jesse S. Michel from Michigan State University, applied Stanley Milgram’s small world phenomenon (i.e., “small world problem”) to the field of I-O psychology through co-author publication linkages. Following six criteria, Scott Highhouse (Bowling Green State University professor and fellow of the Society of Industrial and Organizational Psychology) was chosen as the target. Co-author publication linkages were determined for (1) top authors within the I-O community, (2) quasi-random faculty members of highly productive I-O programs in North America, and (3) publication trends of the target. Results suggest that the small world phenomenon is alive and well with mean linkages of 3.00 to top authors, mean linkages of 2.50 to quasi-random faculty members, and a relatively broad and non-repetitive set of co-author linkages for the target. The author then provided a series of implications and suggestions for future research.

See also

- Connections, a TV documentary that follows a similar concept but involving history and science.

- Erdős number

- Erdős–Bacon number

- Hyperlink Cinema

- Jewish geography

- Professional network service

- Shusaku number

- Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon

- SixDegrees.org

- Small world phenomenon

- Social network

- The Game (mind game)

- The Tipping Point by Malcolm Gladwell

Notes

- ↑ "More than half of all participants resided in North America and were middle class, professional, college educated, and Christian, reflecting commonly held notions of the Internet-using population"[10]

- ↑ "suggesting lack of interest ... was the main reason" for the "extremely low completion rate"[10]

References

- ↑ Newman, Mark, Albert-László Barabási, and Duncan J. Watts. 2006. The Structure and Dynamics of Networks. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- 1 2 Barabási, Albert-László. 2003. Linked: How Everything is Connected to Everything Else and What It Means for Business, Science, and Everyday Life. New York: Plume.

- ↑ Karinthy, Frigyes. Chain-Links. Translated from Hungarian and annotated by Adam Makkai and Enikö Jankó.

- ↑ Gurevich, M (1961) The Social Structure of Acquaintanceship Networks, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

- ↑ de Sola Pool, Ithiel, Kochen, Manfred (1978–1979)."Contacts and influence." Social Networks 1(1): 42

- ↑ de Sola Pool, Ithiel, Kochen, Manfred (1978–1979)."Contacts and Influence." Social Networks 1(1): 5–51

- 1 2 Milgram, Stanley (1967). "The Small World Problem". Psychology Today 2: 60–67.

- ↑ Travers, Jeffrey, and Stanley Milgram, "An Experimental Study of the Small World Problem", Sociometry 32(4, Dec. 1969):425–443

- ↑ "The concept of Six degrees of separation stretches back to Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi". Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- 1 2 3 Dodds, Muhamad, Watts (2003)."Small World Project," Science Magazine. pp.827-829, 8 August 2003 https://www.sciencemag.org/content/301/5634/827

- 1 2 Judith S. Kleinfeld, University of Alaska Fairbanks (January–February 2002). "The Small World Problem" (PDF). Society (Springer), Social Science and Public Policy.

- ↑ Steven Strogatz, Duncan J. Watts and Albert-Laszlo Barabasi "explaining synchronicity, network theory, adaption of complex systems, Six Degrees, Small world phenomenon in the BBC Documentary". BBC. Retrieved 11 June 2012. "Unfolding the science behind the idea of six degrees of separation"

- ↑ BBC News: More Or Less: Connecting With People In Six Steps 13 July 2006, "Judith Kleinfeld ... told us, that 95% of the letters sent out had failed to reach the target."

- ↑ "Six Degrees: Urban Myth? Replicating the small world of Stanley Milgram. Can you reach anyone through a chain of six people.". Psychology Today. March 1, 2002.

- ↑ The Uncontacted Indians of Brazil Survivalinternational

- ↑ Duncan J Watts, Steven H Strogatz (1998). "Collective dynamics of 'small-world' networks". Nature 393 (6684): 440–442. doi:10.1038/30918. PMID 9623998.

- ↑ Jure Leskovec and Eric Horvitz (June 2007). "Planetary-Scale Views on an Instant-Messaging Network". arXiv:0803.0939.

- ↑ Robin Good. "The Power Of Open Participatory Media And Why Mass Media Must Be Abandoned". Robin Good's Master New Media.

- ↑ Billion2One.org

- ↑ Reza Bakhshandeh, Mehdi Samadi, Zohreh Azimifar, Jonathan Schaeffer, "Degrees of Separation in Social Networks", Fourth Annual Symposium on Combinatorial Search, 2011

- ↑ Memorable quotes from Six Degrees of Separation. Accessed Nov. 11, 2006 from IMDB.com.

- 1 2 "Six degrees of separation' theory tested on Facebook". Telegraph. 17 August 2011. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ↑ "Actor's Hollywood career spawned 'Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon'". Telegraph. 6 June 2011. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ↑ http://www.thesweetscience.com/component/content/article/41-articles-of-2005/1514-the-great-john-l-sullivan

- ↑ "ABC TV Shows, Specials & Movies - ABC.com". ABC.

- ↑ Het Nieuwsblad, 25 September 2009 (Dutch)

- ↑ "Connected: The Power of Six Degrees". The Science Channel – Discovery Channel.

- ↑ Israel's Channel 2 website (Hebrew)

- ↑ staff (July 13, 2015). "SIX DEGREES OF EVERYTHING (TRUTV) Premieres Tuesday, August 18". Futon Critic. Retrieved August 12, 2015.

- ↑ Jan. 18, 2007 press release from Network for Good..

- ↑ "Six Degrees: come in, your time is up". K! - the blog of Karl Bunyan.

- ↑ "Six Degrees on Facebook - Facebook". facebook.com.

- ↑ "Facebook Removing 24 Hour Caching Policy on User Data for Developers". insidefacebook.com.

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Barnett, Emma (22 November 2011). "Facebook cuts six degrees of separation to four". Telegraph. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ↑ Backstrom, Lars; Boldi, Paolo; Rosa, Marco; Ugander, Johan; Vigna, Sebastiano (2011-11-19). "Four Degrees of Separation". ArXiv. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- ↑ Ugander, Johan; Karrer, Brian; Backstrom, Lars; Marlow, Cameron. "The Anatomy of the Facebook Social Graph". ArXiv. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- 1 2 "Facebook says there are only 3.57 degrees of separation". Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ↑ Jan, H.Kietzmann; Kristopher, Hermkens; Lan, P.McCarthy; Bruno, S.Silvestre. "Social media? Get serious! Understanding the functional building blocks of social media". Business Horizons 54: 241–251. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2011.01.005. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ↑ Kirkpatrick, David (2010). The Facebook Effect: The Inside Story of the Company That Is Connecting the World. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 1439102120.

- ↑ boyd, d. m; Ellison, N. B. "Social network sites: Definition, history, and scholarship.". Computer-Mediated 13 (1): 210–230. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00393.x.

- ↑ Apr 30, 2010, Six Degrees of Separation, Twitter Style, from Sysomos.

- ↑ Reza Bakhshandeh, Mehdi Samadi, Zohreh Azimifar, Jonathan Schaeffer Degrees of Separation in Social Networks. Fourth Annual Symposium on Combinatorial Search, 2011

- ↑ "MR: Collaboration Distance". ams.org. line feed character in

|title=at position 5 (help) - ↑ "EBS Project". erdosbaconsabbath.com.

- ↑ (Michel, 2007)

External links

- Six Degrees – The new version of the Facebook application originally built by Karl Bunyan.

- Facebook revised policy on caching data – Facebook's revised policy removing the 24-hour limit on caching of user data.

- Facebook Developers Garage London hackathon – The June 2010 Facebook Developers Garage London hackathon at which the new version of the Six Degrees Facebook application was built.

- Find The Bacon – is a site built for finding the connections between actors and the movies they have played in.

- whocanfindme – the quest – Off- and online contest based on the six degrees of separation principle

- Six Degrees Campaign, a climate justice campaign initiated by Friends of the Earth Brisbane based on the principles of small world theory.

- "E-mail Study Corroborates Six Degrees of Separation", a 2003 Scientific American article about a study conducted at Columbia University.

- Could it be a big world? – 2001, Judith Kleinfeld, University of Alaska Fairbanks

- Pumpthemusic Oracle – The 6 degrees theory applied to the musical universe

- The Oracle of Bacon – The 6 degrees theory applied to movies and TV

- Knock, Knock, Knocking on Newton's Door PDF (223 KiB), by Dan Ward – Journal article published by Defense Acquisition University, applies principles from Duncan Watts' book Six Degrees to technology innovation and scientific research.

- http://www.steve-jackson.net/six_degrees/index.html

- Measuring Degrees of Separation – Demonstrates how a small sample size can be used to accurately measure the degrees of separation

- Using The Six Degrees Of Separation concept along with Social Networking to find my birthparents – An adoptee conducts an experiment based on the 6 degrees of separation and the power of social networking, his goal: to get the word out about his birth to as many people as possible until he finds people with answers to his questions.

- Famous Hungarians

- "Chains," or "Chain-Links."

- Cinemadoku - A web game that combines the six degrees of movies and actors concept with the grid logic of Sudoku.

- - IOS and Android application to make a route (chain) between two any INSTAGRAM users.

- 6 Degrees of Music With Vince Gill – The 6 degrees theory applied to music with Vince Gill at the Center

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||