Deforestation in Central America

| Part of a series on |

| Central America |

|---|

|

|

Countries |

|

Culture |

|

Economy |

|

Education |

|

Politics and government |

|

Transportation |

|

Related topics |

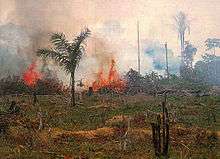

Central American countries have experienced cycles of deforestation and reforestation since the decline of Maya civilization, influenced by many factors such as population growth and agriculture. From 2001 to 2010, 5,376 square kilometers of forest were lost in the region. In 2010 Belize had 63% of remaining forest cover, Costa Rica 46%, Panama 45%, Honduras 41%, Guatemala 37%, Nicaragua 29%, and El Salvador 21%. Most of the loss occurred in the moist forest biome, with 12,201 square kilometers. Woody vegetation loss was partially set off by a plus in the coniferous forest biome with 4,730 km2, and a gain in the dry forest biome at 2,054 km2. Mangroves and deserts contributed only 1% to the loss in forest vegetation. The bulk of the deforestation was located at the Caribbean slopes of Nicaragua with a minus of 8,574 square kilometers of forest lost in the period from 2001 to 2010. The most significant regrowth of 3,050 km2 of forest was seen in the coniferous woody vegetation of Honduras.[1]

History

The history of most Central American countries involves cycles of deforestation and reforestation. For the Ancient Mayan culture at Copan, Honduras, the process of clearing large amounts of land for their agricultural-based society surpassed the forests' ability to replenish naturally. Besides the clearing of land for farmland, Mayans consumed vast quantities of wood as fuel and building materials, rapidly depleting the natural resources of this area. Eventually, the lack of firewood may have caused health problems among those who were unable to properly cook their food or warm their habitations.[2]

By the fifteenth century, intensive Mayan agriculture had significantly thinned the forests, but had not completely decimated them. Before Europeans arrived, forests covered 500,000 square kilometers – approximately 90% of the region. The arrival of the Spaniards caused a sharp decrease in population resulting from the highly contagious diseases introduced by the conquistadores. This reduction in human pressure gave much of the land that had been cleared for cultivation time to recover. Eventually, the forcing of "Europe's money economy on Latin America" created the demand for the exportation of primary products, which introduced the need for large amounts of cleared agricultural land to produce those products.[3] While the cultivation of some exports such as indigo and cochineal dye worked harmoniously with the surrounding indigenous vegetation, other crops such as sugar required clear-cutting of land and mass quantities of firewood to fuel the refining process, which spurred rapid, destructive deforestation.

From the eighteenth to the twentieth century, mahogany exports for furniture became the major cause of forest exhaustion. The region experienced economic change in the nineteenth century through a "fuller integration in the world capitalist system".[3] This, combined with conflict with Spain, put an even greater emphasis on plantation cropping. Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Europe and North America became the chief importers of the regions coffee and banana crops, thus putting increasing demand on the land to produce large quantities of these cash crops and perpetuating the clearing of more forest in an attempt to acquire more exploitable farmland. Most recently, as of the 1960s, cattle ranching has become the primary reason for land clearing. The lean grass-fed cattle produced by Central American ranches (as opposed to grain-fed cattle raised elsewhere) was perfectly suited for American fast-food restaurants and this seemingly bottomless market has created the so-called "hamburger connection" which links "consumer lifestyles in North America with deforestation in Central America".[3] This demonstrates how the developed world has had an indirect influence on the environment and landscape of developing countries.

Logging

Logging is another factor that increases deforestation in multiple ways. Though regulated logging is far less detrimental to the forest, uncontrolled logging is prevalent in developing countries due to the demand for timber to house growing populations, and the poor economic situation of those making their living from and in the forest itself. Furthermore, all forms of logging necessitate the building of roads, which generates easy access to those seeking new land to clear for agriculture. The use of wood as the primary fuel for cooking and heating is compounded by developing countries inability to pay high oil prices. As a result, the demand for firewood is "one of the most commonly cited causes of deforestation".[4]

Narco-deforestation

The so-called "hamburger connection" is not the only example of the indirect impact that consumers in North America have on the environment and landscape in Central America. The pervasion of the illegal drug trade throughout the region decimates forestland and is primarily fueled by demand for narcotics in North America. Honduras, Guatemala, and Nicaragua have suffered from some of the highest rates of deforestation in the world since 2000 and in 2005 these rates of forest loss began to accelerate, coinciding with an influx of drug trafficking activity. Following the election of Felipe Calderón in 2006 and the ignition of the Mexican Drug War, many Mexican drug-trafficking organizations (DTO) relocated their operations southward enticed by the porous borders, corruption, and weak public institutions characteristic of Guatemala and Honduras. The sparsely populated forested highlands in these countries harbor little state presence and offer perfect refuge for DTOs looking to evade interdiction.

The increased trafficking of cocaine through Guatemala and Honduras is correlated with a rise in the region's rate of forest loss. In the forests of eastern Honduras, the amount of newly detected deforestation is greater than 5.29 hectares while in Guatemala's Petén, extensive amounts of forest loss was matched by an unprecedented number of cocaine flows through the area.[5] According to Dr. Kendra McSweeney from Ohio State University, the baseline rate of deforestation in the region of about 20 km2 per year has accelerated to 60 km2 per year under the narco-effect - a deforestation rate of around 10%. In 2011, the Río Plátano Biosphere Reserve in Honduras was designated as a "World Heritage in Danger" by UNESCO due to the striking degree of deforestation at the hands of narco-traffickers.[6]

Three interrelated mechanisms explain the trend of forest loss following the establishment of a drug transit hub. The first is the clearing of forestland for the construction of clandestine roads and airstrips used by vehicles transporting narcotics, pesticides, and fertilizers. Second, the influx of vast amounts of cash and weapons into areas that are already weakly governed only intensifies the preexisting pressures on forests there. The introduction of narco-capital into these frontiers encourages landowners and other actors in the region to participate in the drug trade, which often leaves indigenous communities bereft of their land and livelihoods. Finally, the large profits to drug traffickers incentivize DTOs to convert forest to agriculture in order to launder these profits. "Improving" remote land not only allows narco-traffickers to inconspicuously convert their assets into private earnings but also legitimizes the DTO's presence in the area. Though conversion of land within protected forest area and indigenous communities is illegal, traffickers have the political influence necessary to guarantee impunity. As for the indigenous communities marginalized by increased drug trafficking activity, they are powerless in the face of the narcos' violence and corruption; conservation groups in the region are threatened and state prosecutors are bribed to turn a blind eye to illegal "narco-zones."[5] According to Dr. Kendra McSweeney from Ohio State University, the baseline rate of deforestation in the region of about 20 km2 per year has accelerated to 60 km2 McSweeney cites Honduras' world's highest homicide rate, explaining that conservationists "don't breathe a word of [narco-trafficking], out of fear... they've all been silenced."[6] International environmental groups have pointed to the death of Jairo Mora Sandoval as an example of this sort of silencing of conservationists by narco-traffickers, indicating that the ecological and social effects of the drug trade have been felt throughout Central America.[7]

Population growth

As the countries of this region continue to develop, the sheer number of people, as well as trade with developed countries, puts pressure on natural resources by creating many of the situations previously discussed, such as the necessary clearing of land for agriculture and housing.[8] Another study shows that population growth and technological development in Central America (the Mesoamerican biodiversity hotspot) does in fact have a direct impact on the rate of deforestation.[9]

Global impact

Similarly to the Amazonian rainforest, the Central American forest also "adds to local humidity through transpiration".[10] Without the extra moisture from transpiration, rainfall totals are significantly decreased. Moreover, with less moisture in the air comes the increased susceptibility to fire. These local ramifications are quite serious and affect the quality of life of the surrounding populations, especially the poor, rural peoples who depend on the land for their livelihoods. In addition to the strain on the local environment, the destruction of the rainforests has "a broader impact, affecting global climate and biodiversity".[10]

Efforts to reverse the effects

Many countries have undertaken plans to conserve and replenish the forest in response to the recent upsurge in deforestation. For example, in Nicaragua, forest management consists of shifting from timber to non-timber harvesting alongside sustainable logging methods.[11] In Costa Rica, logging roads that had once added to the problem of deforestation are being researched as potential avenues of reforestation. Furthermore, in the mid-1990s, "damage-controlled logging practices" were implemented to prevent rampant illegal logging.[12]

References

- ↑ Daniel J. Redo, H. Ricardo Grau, T. Mitchell Aide, and Matthew L. Clark. Asymmetric forest transition driven by the interaction of socioeconomic development and environmental heterogeneity in Central America in: Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Jun 5, 2012; 109(23): 8839–8844.

- ↑ Abrams, Elliot M., and David J. Rue. "The Causes and Consequences of Deforestation among the Prehistoric Maya." Human Ecology 16, no. 4 (1988): 377-395.

- 1 2 3 Myers, Norman, and Richard Tucker. "Deforestation in Central America: Spanish Legacy and North American Consumers." Environmental Review: ER 11, no. 1 (1987): 55-71.

- ↑ Allen, Julia C., and Douglas F. Barnes. "The Causes of Deforestation in Developing Countries." Annals of the Association of American Geographers 75, no. 2 (1985): 163-184.

- 1 2 McSweeney, Kendra; Nielsen, Erik; Taylor, Matthew; Wrathall, David; Pearson, Zoe; Wang, Ophelia; Plumb, Spencer (January 31, 2014). "Drug Policy as Conservation Policy: Narco-Deforestation" (PDF). Science 343: 489–490.

- 1 2 McGrath, Matt (30 January 2014). "Drug trafficking is speeding deforestation in Central America". Science & Environment (BBC). BBC. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ↑ Howard, Brian (30 January 2014). "Drug Trafficking Poses Surprising Threats to Rain Forests, Scientists Find". National Geographic (National Geographic Partners, LLC.). National Geographic Society. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ↑ Rudel, Tom, and Jill Roper. "Regional Patterns and Historical Trends in Tropical Deforestation 1976-1990: A Qualitative Comparative Analysis." Ambio 25, no. 3 (1996): 160-166.

- ↑ Jha, S., and K.S. Bawa. "Population Growth, Human Development, and Deforestation in Biodiversity Hotspots." Conservation Biology 20, no. 3 (2006): 906-912

- 1 2 Butler, Rhett. "Global Consequences of Deforestation in the Tropics." Rainforests. http://rainforests.mongabay.com/0901.htm (accessed March 28, 2010).

- ↑ Salick, Jan, Alejandro Mejia, and Todd Anderson. "Non-Timber Forest Products Integrated with Natural Forest Management, Rio San Juan, Nicaragua." Ecological Applications 5, no. 4 (1995): 878-895.

- ↑ Gariguata, Manuel R., and Juan M. Dupuy. "Forest Regeneration in Abandoned Logging Roads in Lowland Costa Rica." Biotropica 29, no. 1 (1997): 15-28.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||