Decimation (signal processing)

In digital signal processing, decimation is the process of reducing the sampling rate of a signal.[1][2][3] Complementary to interpolation, which increases sampling rate, it is a specific case of sample rate conversion in a multi-rate digital signal processing system. Decimation utilises filtering to mitigate aliasing distortion, which can occur when simply downsampling a signal.[3] A system component that performs decimation is called a decimator.[2]

In general

Decimation reduces the data rate or the size of the data. The decimation factor is usually an integer or a rational fraction greater than one. This factor multiplies the sampling time or, equivalently, divides the sampling rate. For example, if 16-bit compact disc audio (sampled at 44,100 Hz) is decimated to 22,050 Hz, the audio is said to be decimated by a factor of 2. The bit rate is also reduced in half, from 1,411,200 bit/s to 705,600 bit/s, assuming that each sample retains its bit depth of 16 bits.

By an integer factor

Decimation by an integer factor, M, can be explained as a 2-step process, with an equivalent implementation that is more efficient:

- Reduce high-frequency signal components with a digital lowpass filter.

- Downsample the filtered signal by M; that is, keep only every Mth sample.

Downsampling alone causes high-frequency signal components to be misinterpreted by subsequent users of the data, which is a form of distortion called aliasing. The first step, if necessary, is to suppress aliasing to an acceptable level. In this application, the filter is called an anti-aliasing filter, and its design is discussed below. Also see undersampling for information about downsampling bandpass functions and signals.

When the anti-aliasing filter is an IIR design, it relies on feedback from output to input, prior to the downsampling step. With FIR filtering, it is an easy matter to compute only every Mth output. The calculation performed by a decimating FIR filter for the nth output sample is a dot product:

where the h[•] sequence is the impulse response, and K is its length. x[•] represents the input sequence being downsampled. In a general purpose processor, after computing y[n], the easiest way to compute y[n+1] is to advance the starting index in the x[•] array by M, and recompute the dot product. In the case M=2, h[•] can be designed as a half-band filter, where almost half of the coefficients are zero and need not be included in the dot products.

Impulse response coefficients taken at intervals of M form a subsequence, and there are M such subsequences (phases) multiplexed together. The dot product is the sum of the dot products of each subsequence with the corresponding samples of the x[•] sequence. Furthermore, because of downsampling by M, the stream of x[•] samples involved in any one of the M dot products is never involved in the other dot products. Thus M low-order FIR filters are each filtering one of M multiplexed phases of the input stream, and the M outputs are being summed. This viewpoint offers a different implementation that might be advantageous in a multi-processor architecture. In other words, the input stream is demultiplexed and sent through a bank of M filters whose outputs are summed. When implemented that way, it is called a polyphase filter.

For completeness, we now mention that a possible, but unlikely, implementation of each phase is to replace the coefficients of the other phases with zeros in a copy of the h[•] array, process the original x[•] sequence at the input rate, and decimate the output by a factor of M. The equivalence of this inefficient method and the implementation described above is known as the first Noble identity.[4]

Anti-aliasing filter

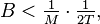

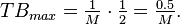

The requirements of the anti-aliasing filter can be deduced from any of the 3 pairs of graphs in Fig. 1. Note that all 3 pairs are identical, except for the units of the abscissa variables. The upper graph of each pair is an example of the periodic frequency distribution of a sampled function, x(t), with Fourier transform, X(f). The lower graph is the new distribution that results when x(t) is sampled 3 times slower, or (equivalently) when the original sample sequence is decimated by a factor of M=3. In all 3 cases, the condition that ensures the copies of X(f) don't overlap each other is the same:  where T is the interval between samples, 1/T is the sample-rate, and 1/2T is the Nyquist frequency. The anti-aliasing filter that can ensure the condition is met has a cutoff frequency less than

where T is the interval between samples, 1/T is the sample-rate, and 1/2T is the Nyquist frequency. The anti-aliasing filter that can ensure the condition is met has a cutoff frequency less than  times the Nyquist frequency.[note 1]

times the Nyquist frequency.[note 1]

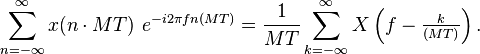

The abscissa of the top pair of graphs represents the discrete-time Fourier transform (DTFT), which is a Fourier series representation of a periodic summation of X(f):

-

![\underbrace{

\sum_{n=-\infty}^{\infty} \overbrace{x(nT)}^{x[n]}\ e^{-i 2\pi f nT}

}_{\text{DTFT}} = \frac{1}{T}\sum_{k=-\infty}^{\infty} X(f-k/T).](../I/m/adcbfe76b2a3d151933708231d81d559.png)

(Eq.1)

When T has units of seconds,  has units of hertz. Replacing T with MT in the formulas above gives the DTFT of the decimated sequence, x[nM]:

has units of hertz. Replacing T with MT in the formulas above gives the DTFT of the decimated sequence, x[nM]:

The periodic summation has been reduced in amplitude and periodicity by a factor of M, as depicted in the second graph of Fig. 1. Aliasing occurs when adjacent copies of X(f) overlap. The purpose of the anti-aliasing filter is to ensure that the reduced periodicity does not create overlap.

In the middle pair of graphs, the frequency variable,  has been replaced by normalized frequency, which creates a periodicity of 1 and a Nyquist frequency of ½. A common practice in filter design programs is to assume those values and request only the corresponding cutoff frequency in the same units. In other words, the cutoff frequency

has been replaced by normalized frequency, which creates a periodicity of 1 and a Nyquist frequency of ½. A common practice in filter design programs is to assume those values and request only the corresponding cutoff frequency in the same units. In other words, the cutoff frequency  is normalized to

is normalized to  The units of this quantity are (seconds/sample)×(cycles/second) = cycles/sample.

The units of this quantity are (seconds/sample)×(cycles/second) = cycles/sample.

The bottom pair of graphs represent the Z-transforms of the original sequence and the decimated sequence, constrained to values of complex-variable, z, of the form  Then the transform of the x[n] sequence has the form of a Fourier series. By comparison with Eq.1, we deduce:

Then the transform of the x[n] sequence has the form of a Fourier series. By comparison with Eq.1, we deduce:

which is depicted by the fifth graph in Fig. 1. Similarly, the sixth graph depicts:

By a rational factor

Let M/L denote the decimation factor, where: M, L ∈ ℤ; M > L.

- Interpolate by a factor of L

- Decimate by a factor of M

Interpolation requires a lowpass filter after increasing the data rate, and decimation requires a lowpass filter before decimation. Therefore, both operations can be accomplished by a single filter with the lower of the two cutoff frequencies. For the M > L case, the anti-aliasing filter cutoff,  cycles per intermediate sample, is the lower frequency.

cycles per intermediate sample, is the lower frequency.

By an irrational factor

Techniques for decimation (and sample-rate conversion in general) by factor R ∈ ℝ+ include polynomial interpolation and the Farrow structure.[5]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Realizable low-pass filters have a "skirt", where the response diminishes from near one to near zero. So in practice the cutoff frequency is placed far enough below the theoretical cutoff that the filter's skirt is contained below the theoretical cutoff.

Citations

- ↑ Lyons, Richard (2001). Understanding Digital Signal Processing. Prentice Hall. p. 304. ISBN 0-201-63467-8.

Decreasing the sampling rate is known as decimation.

- 1 2 Antoniou, Andreas (2006). Digital Signal Processing. McGraw-Hill. p. 830. ISBN 0-07-145424-1.

Decimators can be used to reduce the sampling frequency, whereas interpolators can be used to increase it.

- 1 2 Milić, Ljiljana (2009). Multirate Filtering for Digital Signal Processing. New York: Hershey. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-60566-178-0.

Sampling rate conversion systems are used to change the sampling rate of a signal. The process of sampling rate decrease is called decimation, and the process of sampling rate increase is called interpolation.

- ↑ Strang, Gilbert; Nguyen, Truong (1996-10-01). Wavelets and Filter Banks (2 ed.). Wellesley,MA: Wellesley-Cambridge Press. pp. 100–101. ISBN 0961408871.

- ↑ Milić, Ljiljana (2009). Multirate Filtering for Digital Signal Processing. New York: Hershey. p. 192. ISBN 978-1-60566-178-0.

Generally, this approach is applicable when the ratio Fy/Fx is a rational, or an irrational number, and is suitable for the sampling rate increase and for the sampling rate decrease.

References

- Oppenheim, Alan V.; Schafer, Ronald W.; Buck, John R. (1999). Discrete-Time Signal Processing (2nd ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-754920-2.

- Proakis, John G. (2000). Digital Signal Processing: Principles, Algorithms and Applications (3rd ed.). India: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 8120311299.

| ||||||||||||||||||

![y[n] = \sum_{k=0}^{K-1} x[nM-k]\cdot h[k],](../I/m/de6948c829cd11fa02da96359aa79164.png)

![\sum_{n=-\infty}^{\infty} x[n]\ z^{-n} = \sum_{n=-\infty}^{\infty} x(nT)\ e^{-i\omega n} = \frac{1}{T}\sum_{k=-\infty}^{\infty} \underbrace{X\left(\tfrac{\omega}{2\pi T} - \tfrac{k}{T}\right)}_{X\left(\frac{\omega - 2\pi k}{2\pi T}\right)},](../I/m/a52ada7e6f6673b18f850e1d6f4670b1.png)

![\sum_{n=-\infty}^{\infty} x[nM]\ z^{-n} = \sum_{n=-\infty}^{\infty} x(nMT)\ e^{-i\omega n} = \frac{1}{MT}\sum_{k=-\infty}^{\infty} \underbrace{X\left(\tfrac{\omega}{2\pi MT} - \tfrac{k}{MT}\right)}_{X\left(\frac{\omega - 2\pi k}{2\pi MT}\right)}.](../I/m/0e3f4a2d858096430c8ee09fa337f3f3.png)