De pictura

De pictura (English: "On Painting") is a Latin treatise written by the Italian architect and art theorist Leon Battista Alberti. It was first written in vernacular Italian in 1435 under the title Della pittura, and then in Latin. (See Leon Battista Alberti: On Painting. A New Translation and Critical Edition. Edited and translated by Rocco Sinisgalli, Cambridge University Press, New York, 2011). It is the first in a trilogy of treatises on the "Major arts" which had a widespread circulation during the Renaissance, the others being De re aedificatoria ("On Architecture", 1454) and De statua ("On Sculpture", 1462).

Alberti was a member of Florentine family exiled in the 14th century, who was able to return in Florence only from 1434, in the following of the Papal court during the Council of Florence. Here he knew contemporary art innovators such as Filippo Brunelleschi, Donatello and Masaccio, with whom he shared an interest for Renaissance humanism and classical art. Alberti was the first post-classical writer to produce a work of art theory, as opposed to works about the function of religious art or art techniques, and reflected the developing Italian Renaissance art of his day.

Work

De pictura aimed to describe systematically the figurative arts through "geometry". Alberti divided painting into three parts:

- Circumscriptio (Italian: disegno), consisting in drawing the bodies' contour

- Compositio (commensuratio in the Italian version of the treatise), including tracing the lines joining the bodies

- Receptio luminum (color), taking into consideration colors and light.

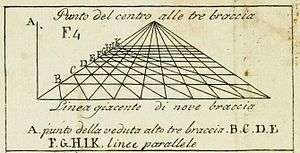

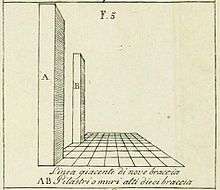

The treatise contained an analysis of all the techniques and painting theories known at the time, in this surpassing medieval works such as The book of Art by Cennino Cennini (1390). De pictura also includes the first description of linear geometric perspective devised by Brunelleschi around 1416; the invention was explicitly credited by Alberti to the Florentine architect, to whom was dedicated the 1435 edition.

Alberti argued that multi-figure history painting was the noblest form of art, as being the most difficult, which required mastery of all the others, because it was a visual form of history, and because it had the greatest potential to move the viewer. He placed emphasis on the ability to depict the interactions between the figures by gesture and expression.[1] The work relied heavily on references to art in classical literature; in fact Giotto's huge Navicella in mosaic at Old St. Peter's Basilica in Rome (now effectively lost) was the only modern (post-classical) work described in it.

Notes

- ↑ Blunt, 11-12; Barlow, 1

References

- Barlow, Paul, "The Death of History Painting in Nineteenth-Century Art?" PDF, Visual Culture in Britain, Volume 6, Number 1, Summer 2005, pp. 1–13(13)

- Blunt, Anthony, Artistic Theory in Italy, 1450-1660, 1940 (refs to 1985 edn), OUP, ISBN 0-19-881050-4

- Rocco, Sinisgalli, On Painting. A New Translation and Critical Edition, 2011, publisher, Cambridge University Press, New York, ISBN 978-1-107-00062-9.