de Havilland Vampire

| Vampire Sea Vampire | |

|---|---|

| |

| Vampire T.11 of the UK Vampire Preservation Group displays at the Cotswold Air Show | |

| Role | Fighter aircraft |

| Manufacturer | de Havilland English Electric |

| First flight | 20 September 1943 |

| Introduction | 1945 |

| Retired | 1979 Rhodesian Air Force |

| Primary users | Royal Air Force Fleet Air Arm |

| Number built | 3,268[1] |

| Developed into | de Havilland Venom |

The de Havilland DH.100 Vampire was a British jet fighter developed and manufactured by de Havilland. Having been developed during the Second World War to harness the newly developed jet engine, the Vampire entered service with the Royal Air Force (RAF) in 1945. It was the second jet fighter, after the Gloster Meteor, operated by the RAF, and its first to be powered by a single jet engine.

The RAF used the Vampire as a front-line fighter until 1953, when it was given secondary roles such as pilot training, although 103 Flying Refresher School had them deployed in that role from 1951. It was retired by the RAF in 1966, replaced by the Hawker Hunter and Gloster Javelin. It achieved several aviation firsts and records, including being the first jet aircraft to cross the Atlantic Ocean. The Vampire had many export sales and was operated by various air forces. It participated in conflicts including the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, the Malayan emergency and the Rhodesian Bush War.

Almost 3,300 Vampires were manufactured, a quarter of them built under licence in other countries. The Royal Navy's first jet fighter was the Sea Vampire, a navalised variant which was operated from its aircraft carriers. The Vampire was developed into the DH.115 dual-seat trainer and the more advanced DH.112 Venom ground-attack and night fighter.

Development

Origins

Under Air Ministry specification E.6/41 for two prototypes, design work on the DH.100 began at the de Havilland works at Hatfield in mid-1942, two years after the Meteor.[2] Originally named the "Spider Crab," the aircraft was entirely a de Havilland project, exploiting the company's extensive experience in building with moulded plywood for aircraft construction. Many of the basic design features were first used in their Mosquito fast bomber. It had conventional straight mid-wings and a single jet engine placed in an egg-shaped, aluminium-skinned fuselage, exhausting in a straight line.

The Vampire was considered to be a largely experimental design due to its unorthodox arrangement and the use of a single engine, unlike the Gloster Meteor which was already specified for production. The low power output of early British jet engines meant that only twin-engine aircraft designs were considered practical; but as more powerful engines were developed, particularly Frank Halford's H.1 (later known as the Goblin), a single-engined jet fighter became possible. De Havilland were approached to produce an airframe for the H.1, and their first design, the DH.99, was an all-metal, twin-boom, tricycle undercarriage aircraft armed with four cannon. The use of a twin boom kept the jet pipe short, avoiding the power loss of a long pipe that would have been needed in a conventional fuselage. The DH.99 was modified to a mixed wood and metal construction in light of Ministry of Aircraft Production recommendations, and the design was renumbered to DH.100 by November 1941.[3]

Geoffrey de Havilland Jr, the de Havilland chief test pilot and son of the company's founder, test flew prototype serial number LZ548/G on its maiden flight on 20 September 1943 from Hatfield.[4] The flight took place only six months after the Meteor's maiden flight. The first Vampire flight had been delayed due to the need to send the only available engine fit for flight to America to replace one destroyed in ground engine runs in Lockheed's prototype XP-80. The production Vampire Mk I did not fly until April 1945, with most being built by English Electric Aircraft at their Preston, Lancashire factories due to the pressures on de Havilland's production facilities, which were busy with other types. Although eagerly taken into service by the RAF, it was still being developed at war's end, and never saw combat in the Second World War.

Further development

De Havilland initiated a private venture night fighter, the DH.113 intended for export, fitting a two-seat cockpit closely based on that of the Mosquito night fighter, and a lengthened nose accommodating AI Mk X radar. An order to supply the Egyptian Air Force was received, but this was blocked by the British government as part of a general ban on supplying arms to Egypt. Instead the RAF took over the order and put them into service as an interim measure between the retirement of the de Havilland Mosquito night fighter and the full introduction of the Meteor night fighter.[5] Removal of the radar from the night fighter and fitting of dual controls gave a jet trainer, the DH.115 Vampire which entered British service as the Vampire T.11. This was built in large numbers, both for the RAF and for export.[6]

A total of 3,268 Vampires were built in 15 versions, including a twin-seat night fighter, a trainer and a carrier-based aircraft designated Sea Vampire. The Vampire was used by some 31 air forces. Germany, the Netherlands, Spain and the U.S. were the only major Western powers not to use the aircraft type.

In 1947 Wing Commander Maurice Smith, editor of Flight magazine, stated upon piloting his first jet-powered aircraft, a Vampire Mk III: "Piloting a jet aircraft has confirmed one opinion I had formed after flying as a passenger in the Lancastrian jet test beds, that few, if any, having flown in a jet-propelled transport, will wish to revert to the noise, vibration and attendant fatigue of an airscrew-propelled piston-engined aircraft".[7]

Records and achievements

On 8 June 1946, the Vampire was introduced to the British public when Fighter Command's 247 Squadron was given the honour of leading the flypast over London at the Victory Day Celebrations.[8] The Vampire was a versatile aircraft, setting many aviation firsts and records, being the first RAF fighter with a top speed exceeding 500 mph (800 km/h). On 3 December 1945, a Sea Vampire piloted by Captain Eric "Winkle" Brown became the first pure-jet aircraft to land on and take off from an aircraft carrier.[9][N 1]

Vampires were used in trials from 1947 to 1955 to develop undercarriage-less fighters that could operate from flexible rubber decks on aircraft carriers, which would allow the weight and complication of an undercarriage to be eliminated.[11] Despite demonstrating that the technique was practicable, with many landings being made with undercarriage retracted on flexible decks both at RAE Farnborough and on board the carrier HMS Warrior, the proposal was not taken further.[12] On 23 March 1948, John Cunningham, flying a modified Mk I with extended wing tips and powered by a de Havilland Ghost engine, set a new world altitude record of 59,446 ft (18,119 m).[13]

On 14 July 1948, six Vampire F.3s of No. 54 Squadron RAF became the first jet aircraft to fly across the Atlantic Ocean when they arrived in Goose Bay, Labrador. They went via Stornoway in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland, Keflavik in Iceland and Bluie West 1, Greenland. From Goose Bay airfield they went on to Montreal (c. 3,000 mi/4,830 km) to start the RAF's annual goodwill tour of Canada and the US, where they gave formation aerobatic displays.[14] At the same time USAF Colonel David C. Schilling led a group of F-80 Shooting Stars flying to Fürstenfeldbruck Air Base in Germany to relieve a unit based there. There were conflicting reports later regarding competition between the RAF and USAF to be the first to fly the Atlantic. One report said the USAF squadron delayed completion of its movement to allow the Vampires to be "the first jets across the Atlantic".[15] Another said that the Vampire pilots celebrated “winning the race against the rival F-80s.”[16]

Design

The Vampire was first powered by a Halford H1 (later called the "Goblin") producing 2,100 lbf (9.3 kN) of thrust, designed by Frank B Halford and built by de Havilland. The engine was a centrifugal-flow type, a design later superseded after 1949 by the slimmer axial-flow units. Initially, the Goblin gave the aircraft a disappointingly limited range. This was a common problem with all the early jets, and later marks were distinguished by greatly increased fuel capacities. As designs improved the engine was often upgraded. Later Mk Is used the Goblin II; the F.3 onwards used the Goblin III. Certain marks were test-beds for the Rolls-Royce Nene, leading to the FB30 and 31 variants built in Australia. Due to the low positioning of the engine, a Vampire could not remain on idle for long as the heat from the jet exhaust would melt the tarmac behind the aircraft.

Operational history

RAF and Royal Navy service

In postwar service, the RAF employed the Gloster Meteor as an interceptor and the Vampire as a ground-attack fighter-bomber (although their roles probably should have been reversed).[N 2]

The first prototype of the "Vampire Fighter-Bomber Mk 5" (FB.5), modified from a Vampire F.3, carried out its initial flight on 23 June 1948. The FB.5 retained the Goblin III engine of the F.3, but featured armour protection around engine systems, wings clipped back by 1 ft (30 cm), and longer-stroke main landing gear to handle greater takeoff weights and provide clearance for stores/weapons load. An external tank or 500 lb (227 kg) bomb could be carried under each wing, and eight "3-inch" rocket projectiles ("RPs") could be stacked in pairs on four attachments inboard of the booms. Although an ejection seat was considered, it was not fitted.

At its peak, 19 RAF squadrons flew the FB.5 in Europe, the Middle East and the Far East. The FB.5 undertook attack missions during the British Commonwealths campaign to suppress the insurgency in Malaya in the late 1940s and early 1950s. The FB.5 fighter-bomber became the most numerous single-seat variant with 473 aircraft produced.

The NF.10 served from 1951 to 1954 with three squadrons (23, 25 and 151) but was often flown in daytime as well as night time. After replacement by the Venom conversions were made to NF(T).10 standard for operation by the Central Navigation and Control School at RAF Shawbury. Others were sold to the Indian Air Force.

The RAF eventually relegated the Vampire to advanced training roles in the mid-1950s, and the type was generally out of RAF service by the end of the decade.

Following carrier-landing trials on the carrier HMS Ocean with a modified prototype Vampire, the Royal Navy ordered a navalised variant of the Vampire FB.5 as the Sea Vampire, the first Royal Navy jet aircraft. Two prototypes were followed by 18 production aircraft which were used to gain experience in carrier jet operations before the arrival of the two-seat Sea Vampire T.22 trainers.[18]

The final Vampire was the T (trainer) model. First flown from the old Airspeed Ltd factory at Christchurch, Hampshire on 15 November 1950, production deliveries of the trainer began in January 1952. Over 600 examples of the T.11 were produced at Hatfield and Chester and by Fairey Aviation at Manchester Airport, in both air force and naval models. The T models remained in service with the RAF until 1966. There was a Vampire trainer in service at CFS RAF Little Rissington until at least January 1972.

Australia

In 1946 approval was given for the purchase of an initial 50 Vampire aircraft for the RAAF. The first three machines were British-built aircraft, an F1, F2 and FB.5, and were given serial numbers A78-1 to A78-3.

The second aircraft, the F2 (A78-2), was significant in that it was powered by the more powerful Rolls-Royce Nene jet engine, rather than the usual Goblin. All 80 F.30 fighters and FB.31 fighter-bomber aircraft built by de Havilland Australia were to be powered by Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation versions of the Nene engine manufactured under licence in Melbourne. The Nene required a greater intake cross-section than the Goblin, and the initial solution was to mount auxiliary intakes on top of the fuselage behind the canopy. Unfortunately these intakes led to elevator blanking on formation of shock waves, and three aircraft and pilots were lost in unrecoverable dives. All Nene-engined aircraft were later modified to have the auxiliary intakes beneath the fuselage, thus avoiding the problem.

The first Vampire F.30 fighter (A79-1) flew in June 1949, and it was followed by 56 more F.30 variants before the final 23 aircraft were completed as FB.31s with strengthened and clipped wings with underwing hardpoints. The last FB.31 was delivered in August 1953, and 24 late-production F.30s were subsequently upgraded to FB.31 standard. Single seat Vampires were retired in the RAAF in 1954.

The T.33, T.34 and T.35 were used by the RAAF and the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) (known as Mk33 through to Mk35W in RAAF service) and many were manufactured or assembled at de Havilland Australia's facilities in Sydney. The Mk35W was a Mk35 fitted with spare Mk33 wings following overstress or achievement of fatigue life. Vampire trainer production in Australia amounted to 110 aircraft, and the initial order was filled by 35 T.33s for the RAAF, deliveries being made in 1952 with five T.34s for the RAN delivered in 1954. The trainers remained in service in the RAAF until 1970 while RAN Vampires were retired in 1971.[19]

Canada

An F.1 version began operating on an evaluation basis in Canada at the Winter Experimental Establishment in Edmonton in 1946. The F.3 was chosen as one of two types of operational fighters for the Royal Canadian Air Force and was first flown in Canada on 17 January 1948 where it went into service as a Central Flying School training aircraft at RCAF Station Trenton. With 86 in total, the F.3 was the first jet fighter to enter RCAF service in any significant numbers. It served to introduce fighter pilots not only to jet flying, but also to cockpit pressurization and the tricycle landing gear. The "Vamp" was a popular aircraft, easy to fly and considered a "hot rod."[20] It served in both operational and air reserve units (400, 401, 402, 411, 438 and 442 squadrons) until retirement in the late 1950s when it was replaced by the Canadair Sabre.[21]

Egypt

In 1954 Egypt was operating 49 Vampires, acquired from Italy and Britain, as fighter-bombers.[22] In 1955 twelve Vampire trainers were ordered, with delivery starting in July that year.[23] The Egyptian Air Force lost three Vampires in combat with Israeli jets during the Suez Crisis.

Finland

The Finnish Air Force received six FB.52 Vampires in 1953. The model was nicknamed "Vamppi" in Finnish service. An additional nine twin-seat T.55s were purchased in 1955. The aircraft were assigned to 2nd Wing at Pori, but were transferred to 1st Wing at Tikkakoski at the end of the 1950s. The last Finnish Vampire was decommissioned in 1965.

India

No. 7 Squadron, Indian Air Force (IAF) received Vampires in January 1949. Although the unit was put on high alert during the Sino-Indian War of 1962, it did not see any action, as the air force's role was limited to supply and evacuation. No. 17 Squadron IAF also operated the type.

On 1 September 1965, during the Indo-Pakistani War, IAF Vampires saw action for the first time. No. 45 Squadron responded to a request for strikes against a counter-attack by the Pakistani Army (Operation Grand Slam) and four Vampire Mk 52 fighter-bombers were successful in slowing the Pakistani advance. However, the Vampires encountered two Pakistan Air Force (PAF) F-86 Sabres, armed with air-to-air missiles; in the ensuing dogfight, the outdated Vampires were outclassed. One was shot down by ground fire and another three were shot down by Sabres.[24] The Vampires were withdrawn from front line service after these losses.

Norway

The Royal Norwegian Air Force purchased 20 Vampires F.3s, 36 FB.52s and six T.55 trainers. The Vampire was in use in Norway from 1948 to 1957 equipping a three-squadron Vampire wing at Gardermoen. The Vampires were withdrawn in 1957 when the air force re-equipped with the Republic F-84G Thunderjet. The Vampire trainers were replaced by the Lockheed T-33 in 1955 and returned to the United Kingdom and used by the Royal Air Force.

Sweden

The Swedish Air Force purchased its first batch of 70 FB 1 Vampires in 1946, looking for a jet to replace the already outdated SAAB 21 and J 22s of its fighter force. The aircraft was designated J 28A and was assigned to the F 13 Norrköping Wing. It provided such good service that it was selected as the backbone of the fighter force. A total of 310 of the more modern FB.50, designated J 28B, were purchased in 1949. The last one was delivered in 1952, after which all piston-engined fighters were decommissioned. In addition, a total of 57 two-seater DH 115 Vampires called J 28C were used for training.

The Swedish Vampires were retired as fighters in 1956 and replaced with J 29 (SAAB Tunnan) and J 34 (Hawker Hunter). The last Vampire trainer was retired in 1968.

Switzerland

_Vampire_T55_(DH-115)_AN2244396.jpg)

The Swiss Air Force purchased in 1946 four DH-100 F.1. (J-1001 to J-1004). One aircraft crashed on 2 August 1946, the other three remained in service until 1961. The first batch of 75 DH-100 Mk.6 (J-1005 to J-1079) was purchased in 1949. Most of them passed out of service in 1968/1969, the last ones in 1973. The second batch was 100 DH-100 Mk.6 (J-1101 to J-1200) built under licence by the Swiss aviation industry. In use from 1951 to 1974 and in storage until 1988. Three DH-100 Mk.6 (J-1080 to J-1082) were built from spare parts. One DH.113 NF.10 (J-1301) 1958 to 1961. 39 DH-115 Mk 55 Vampire two-seat trainers (U-1201 to U-1239) from 1953 to 1990.[25][26]

Rhodesia

_(8643525896).jpg)

The Rhodesian Air Force acquired 16 Vampire FB.9 fighters and a further 16 Vampire T.11 trainers in the early 1950s, its first jet aircraft, equipping two squadrons.[27] These were regularly deployed to Aden between 1957 and 1961, supporting British counter-insurgency operations.[28] 21 more two-seaters and 13 single-seaters were supplied by South Africa in the late 1960s and early 1970s.[29] Rhodesia operated Vampires until the end of the bush war in 1979. In 1977, six were pressed into service for Operation Dingo. They were eventually replaced by the BAe Hawk 60 in the early 1980s. After 30 years service, they were the last Vampires used on operations anywhere in the world.[30]

Variants

- DH.100: three prototypes to specification E.6/41.

- LZ548 first flown 20 September1943

- LZ551 first flown 17 March 1944 and modified for deck landing trials, the first jet aircraft to land on an aircraft carrier, on display in 2013 at the Fleet Air Arm Museum.

- MP838 first flown on 21 January 1944, the first armed aircraft.

- Vampire Mk I: single-seat fighter version for the RAF; 244 production aircraft being built.

- Mk II: three prototypes, with Rolls-Royce Nene turbojet engine. One built and two conversions.

- F.3: single-seat fighter for the RAF. Two prototypes were converted from the Mk 1; 202 production aircraft were built, 20 were exported to Norway

- Mk IV: Nene-engined project, not built.

- FB.5: single-seat fighter-bomber version. Powered by the Goblin 2 turbojet; 930 built for the RAF and 88 for export.

- FB.6: single-seat fighter-bomber. Powered by a Goblin 3 turbojet; 178 built, 100 built in Switzerland for the Swiss Air Force.

- Mk 8: Ghost-engined, one conversion from Mk 1.

- FB.9: tropicalised fighter-bomber through addition of air conditioning to Mark 5. Powered by Goblin 3 turbojet; 326 built, mostly by de Havilland, but also by Fairey Aviation.

- Mk 10 or DH.113 Vampire: Goblin-powered two-seater prototype; two built.

- NF.10: two-seat night fighter version for the RAF; 95 built including 29 as the NF.54.

- Sea Vampire Mk 10: prototype for deck trials. One conversion.

- Mk 11 or DH.115 Vampire Trainer: private venture, two-seat jet trainer prototype.

- T.11: two-seat training version. Powered by a Goblin 35 turbojet; 731 were built by DH and Fairey Aviation. Some fitted with ejection seats.

- Sea Vampire F.20: naval version of the FB.5; 18 built by English Electric.

- Sea Vampire F.21: six aircraft converted from F.3s with strengthened belly and arrester hook for trials of undercarriage-less landings on flexible decks.[31]

- Sea Vampire T.22: two-seat training version for the Royal Navy; 73 built by De Havilland.

- FB.25: FB.5 variants; 25 exported to New Zealand

- F.30: single-seat fighter-bomber version for the RAAF. Powered by Rolls-Royce Nene turbojet; 80 built in Australia.

- FB.31: Nene-engined, 29 built in Australia.

- F.32: one Australian conversion with air conditioning.

- T.33: two-seat training version. Powered by the Goblin turbojet; 36 were built in Australia.

- T.34: two-seat training version for the Royal Australian Navy; five were built in Australia.

- T.34A: Vampire T.34s fitted with ejection seats.

- T.35: modified two-seat training version; 68 built in Australia.

- T.35A: T.33 conversions to T.35 configuration.

- FB.50: exported to Sweden as the J 28B; 310 built, 12 of which were eventually rebuilt to T.55 standard.

- FB.51: export prototype (one conversion) to France.

- FB.52: export version of Mk 6, 101 built; 36 exported to Norway and in use from 1949 to 1957

- FB.52A: single-seat fighter-bomber for the Italian Air Force; 80 built in Italy.

- NF.54: export version of Vampire NF.10 for the Italian Air Force; 29 being built.

- T.55: export version of the DH.115 trainer; 216 built and six converted from the T.11.

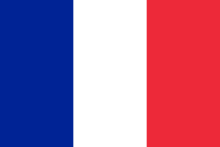

- S.N.C.A.S.E. 'Vampire' FB.53: Four pre-series single-seat fighter-bombers for the Armee de l'Air; 250 built in France, as the Sud-Est SE 535 Mistral.

- S.N.C.A.S.E. SE-532 Mistral: Initial production version of the Mk.53 for the Armée de l'Air; 97 built.

- S.N.C.A.S.E. SE-535 Mistral: Development of the SE-532, 150 built for the Armée de l'Air.

Operators

.jpg)

Austria

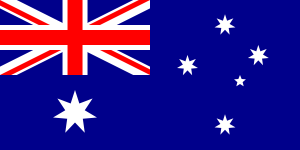

Austria Australia

Australia.svg.png) Burma

Burma Canada

Canada.svg.png) Ceylon

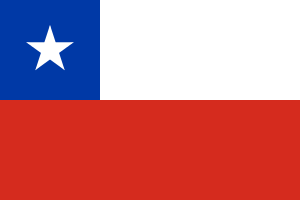

Ceylon Chile

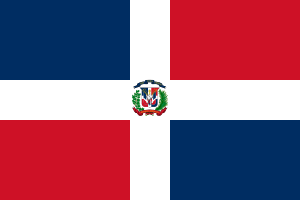

Chile Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Egypt

Egypt Finland

Finland France

France India

India Indonesia

Indonesia.svg.png) Iraq

Iraq Ireland

Ireland Italy

Italy Japan

Japan Jordan

Jordan Katanga

Katanga Lebanon

Lebanon Mexico

Mexico New Zealand

New Zealand Norway

Norway Portugal

Portugal Rhodesia

Rhodesia Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia.svg.png) South Africa

South Africa Sweden

Sweden Switzerland

Switzerland Syria

Syria United Kingdom

United Kingdom.svg.png) Venezuela

Venezuela Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe

Survivors

Although 80+ Vampires are still airworthy, only a small number are flying:

Switzerland - Two DH-100 Mk.6(HB-RVH & HB-RVN) and two DH-115 Trainer (HB-RVF & HB-RVJ)

Switzerland - Two DH-100 Mk.6(HB-RVH & HB-RVN) and two DH-115 Trainer (HB-RVF & HB-RVJ)

Norway - Two other ex-Swiss vampires, a T.55 and an FB.52 are operated by the Norweigian Airforce Historical Squadron, and fly at many displays in Europe[34]

Norway - Two other ex-Swiss vampires, a T.55 and an FB.52 are operated by the Norweigian Airforce Historical Squadron, and fly at many displays in Europe[34]

United Kingdom - An ex-Swiss Vampire T.55 was brought to the UK and repainted in RAF camouflage, and is now operated by the Classic Air Force out of Coventry airport registered as G-HELV.[35] An airworthy Vampire T.11 is operated by the Vampire Preservation Group from North Weald in Essex, UK.[36]

United Kingdom - An ex-Swiss Vampire T.55 was brought to the UK and repainted in RAF camouflage, and is now operated by the Classic Air Force out of Coventry airport registered as G-HELV.[35] An airworthy Vampire T.11 is operated by the Vampire Preservation Group from North Weald in Essex, UK.[36]

USA - Several ex-Swiss and ex-Australian Vampires operate as collectors' aircraft in the United States. Several other US-based Vampires are abandoned and in disrepair.

USA - Several ex-Swiss and ex-Australian Vampires operate as collectors' aircraft in the United States. Several other US-based Vampires are abandoned and in disrepair.

Australia - One ex-Australian two-seat Mk 35W Vampire, S/N A79-617 was restored by Red Star Aviation of Hackettstown, New Jersey and then repatriated to Australia, where it is displayed in air shows. Two ex-RAAF Mk 35s (A79-637 and A79-665) are owned by the Historical Aircraft Restoration Society (HARS) at Illawarra Regional Airport, NSW, one of which is being restored to flying condition.

Australia - One ex-Australian two-seat Mk 35W Vampire, S/N A79-617 was restored by Red Star Aviation of Hackettstown, New Jersey and then repatriated to Australia, where it is displayed in air shows. Two ex-RAAF Mk 35s (A79-637 and A79-665) are owned by the Historical Aircraft Restoration Society (HARS) at Illawarra Regional Airport, NSW, one of which is being restored to flying condition.

New Zealand - An ex-RNZAF T.11 is being restored at the New Zealand Fighter Pilots Museum.[37]

New Zealand - An ex-RNZAF T.11 is being restored at the New Zealand Fighter Pilots Museum.[37]

South Africa - As of November 2015, serial numbers 276 and 277 are flown by the SA Air Force Museum and a third flyable Vampire is at Wonderboom Airport.

South Africa - As of November 2015, serial numbers 276 and 277 are flown by the SA Air Force Museum and a third flyable Vampire is at Wonderboom Airport.

Survivor accidents

On 6 June 2009, the world's oldest flying jet, a Vampire built in 1947, formerly of the RCAF and owned by the Wings of Flight Air Museum in Batavia, New York, crashed during an emergency landing at Rochester International Airport. The aircraft had just taken off to fly to Batavia but returned due to engine trouble. Experiencing a total flameout the pilot belly landed on the grass parallel to the runway. The aircraft struck a berm near the taxiway which caused substantial damage.[38] The pilot escaped with minor injuries. The aircraft had previously been restored with funding from actor John Travolta.

In August 2014, a privately owned ex-Swiss Air Force Vampire T-55 suffered a nose gear failure upon landing, resulting in minor damage to the aircraft. It is expected to be repaired and returned to flyable service.

Aircraft on display

Examples of the de Havilland Vampire on display include:

- Australia

Fighter World, Williamtown, NSW. A79-1 the first jet aircraft to be built in Australia.

- Forbes, New South Wales. Monument next to Lake Forbes, ex-RAAF A79-109.

- Tamworth, Australia, Hands of Fame Park.

- Temora Aviation Museum, New South Wales, ex-RAAF A79-617 (Flying condition)

- Wagga Wagga, New South Wales, ex-RAAF A79-612 on pylon in Bolton Park next to the Sturt Highway

- Wingham, New South Wales ex-RAAF A79-593 on pylon in Central Park.

- Braybrook, Victoria, Central West Plaza shopping centre.

- Gnangara Road, Landsdale, Perth, Western Australia - "Snoopy" on a pylon next to a machinery yard.

- Austria

- Austrian Airforce Museum Zeltweg/Styria (Zeltweg Air Base) (Vampire Two Seat Trainer).

- Belgium

- Royal Museum of the Armed Forces and Military History (Vampire T.11)

- Canada

- Aero Space Museum, Calgary, Alberta (Vampire F.3)[39]

- Alberta Aviation Museum (Vampire T.35 (1964))[40]

- Canada Aviation and Space Museum (Vampire Mk 3).[41]

- Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum.[42]

- Canadian Museum of Flight.[43]

- Comox Air Force Museum (Vampire Mk 3).[44]

- Reynolds-Alberta Museum.

- Chile

- Museo Nacional Aeronáutico y del Espacio, two examples, one is being refurbished for display during 2014.

- One example exhibited inside Cerro Moreno, Antofagasta AFB.

- One example as gate guardian of Diego Aracena AFB of Iquique.

- An example placed in a restaurant of Antofagasta city in northern Chile.

- A Vampire was previously placed on a pole in the intersection of Gran Avenida and Américo Vespucio in Santiago, Chile but was destroyed due to a bombing attack in the 1980s, remains are in the open at Los Cerrillos Museo Aeronáutico.

- Czech Republic

- Letecke Muzeum Kbely.

- Finland

- Aviation Museum of Central Finland (three examples of Vampire Mk 52 and two examples of Mk 55 in storage).

- Finnish Aviation Museum (one Vampire Mk.52 and one Vampire T.55 trainer)[45]

- Germany

- India

- Indian Air Force Museum, Palam, New Delhi.

- Naval Aviation Museum Goa.

- Air Force Technical College, Bangalore.

- Indonesia

- Indonesian Air Force Dirgantara Mandala Museum, Adisutjipto Air Force Base, Yogyakarta.

- Ireland

- Collins Barracks (Dublin) as part of the National Museum of Ireland.

- Israel

- Italy

- Volandia (DH-100 FB.6).[47]

- Italian Air Force Museum (DH-113 NF Mk.54).[48]

- Japan

- Japan Air Self-Defense Force Hamamatsu Air Base Publication Center in Hamamatsu, Japan (Vampire T.55).

- Lebanon

- Lebanese Air Force Museum at Rayak Air Base in Rayak. A de Havilland Vampire T.55 is on display.[49]

- Malta

- Malta Aviation Museum, Ta' Qali in Malta. (Vampire T.11).

- México

- Mexican Military Aviation Museum in Mexico. (Vampire Mk.I).

- Mexican Army and Air Force Museum in Jalisco. (Vampire Mk.I).

- New Zealand

- Museum of Transport and Technology in Auckland, New Zealand (Vampire FB.9).[50]

- RNZAF Ohakea (Vampire FB.9) gate guard.[51]

- Royal New Zealand Air Force Museum.[52]

- Southward Car Museum.

- Ashburton Aviation Museum (Vampire T.11).

- Poland

- Polish Aviation Museum, Kraków, Swiss-built Mk.6.

- Saudi Arabia

- South Africa

- SAAF 205 FB.52 South African Air Force Museum, AFB Port Elizabeth, Static display.

- SAAF 208 FB.52 South African Air Force Museum, AFB Ysterplaat, Cape Town, Static display.[53]

- SAAF 229 FB.52 South African Air Force Museum, AFB Swartkop, Pretoria, Static Display.[54]

- SAAF 277 TMk55 South African Air Force Museum, AFB Swartkop, Pretoria, Airworthy.[55]

.jpg)

- United Kingdom

- F.1 VF301 on display at the Midland Air Museum, Coventry, England.[56]

- FB.5 WA346 under restoration at the Royal Air Force Museum Cosford, England.

- T.11 XD593 on display at the Newark Air Museum, England.[57]

- T.11 XD626 on display at the Midland Air Museum, Coventry, England.[56]

- T.11 XE855 on display at the Midland Air Museum, Coventry, England.[56]

- T.11 XH278 On display at Yorkshire Air Museum, Elvington, Yorkshire.[58]

- T.11 XH313 on display at the Tangmere Military Aviation Museum, England[59]

- T.11 XJ772 on display at the de Havilland Aircraft Heritage Centre, Hertfordshire, England[60]

- T.11 XK590 on display at the Wellesbourne Wartime Museum, Warwickshire, England.[61]

- T.11 XK624 on display at the Norfolk and Suffolk Aviation Museum, Flixton, England.[62]

- T.11 WZ515 on display at the Solway Aviation Museum, Carlisle, England.[63]

- T.11 WZ518 on display at the North East Aircraft Museum, Sunderland, England.[64]

- T.11 WZ590 on display at the Imperial War Museum Duxford, England.

- T.11 on display at Headquarters No. 2247 (Hawarden) Squadron Air Training Corps, Hawarden, Flintshire, Wales.

- T.22 XA109 on display at Montrose Air Station Heritage Centre, Angus, Scotland.[65]

- United States

- Pima Air & Space Museum, adjacent to Davis-Monthan AFB in Tucson, Arizona.[66]

- Evergreen Aviation Museum in McMinnville, Oregon.

- Planes of Fame Air Museum in Valle-Williams Arizona.

- An ex-Swiss example is displayed at the Quonset Air Museum, North Kingstown, RI, USA, and is owned and flown by the Red Star Aviation Museum.

- Venezuela

- FB.52 (3C35) and T.11 (IE35) at the Aeronautics Museum of Maracay, Venezuela.[67]

Specifications (Vampire FB.6)

Data from The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Aircraft[68]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 30 ft 9 in (9.37 m)

- Wingspan: 38 ft (11.58 m)

- Height: 8 ft 10 in (2.69 m)

- Wing area: 262 ft² (24.34 m²)

- Empty weight: 7,283 lb (3,304 kg)

- Max. takeoff weight: 12,390 lb [69] (5,620 kg)

- Powerplant: 1 × de Havilland Goblin 3 centrifugal turbojet, 3,350 lbf (14.90 kN)

Performance

- Maximum speed: 548 mph (882 km/h)

- Range: 1,220 mi (1,960 km)

- Service ceiling: 42,800 ft (13,045 m)

- Rate of climb: 4,800 ft/min[69] (24.4 m/s)

Armament

- Guns: 4 × 20 mm (0.79 in) Hispano Mk.V cannon with 600 Rounds total (150 RPG).

- Rockets: 8 × 3-inch "60 lb" rockets

- Bombs: or 2 × 500 lb (225 kg) bombs or two drop-tanks

Notable appearances in media

See also

- Portal:British aircraft since World War II

- Related development

- Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Related lists

References

Notes

- ↑ On 6 November 1945, a Ryan FR Fireball, designed to utilize its piston engine during takeoff and landing, had a piston engine failure on final approach. The pilot started the jet engine, performing the first jet-powered carrier landing, albeit unintentionally, although the Fireball was not a high performance jet fighter like the Vampire.[10]

- ↑ Quote: "The Vampire had been conceived during the war as a high-altitude fighter..."[17]

Citations

- ↑ Gunston 1981, p. 52.

- ↑ Gunston 1981, p. 49.

- ↑ Buttler 2000, p. 201.

- ↑ Gunston 1981, p. 50.

- ↑ Jackson 1987, p. 484.

- ↑ Jackson 1987, pp. 496—501.

- ↑ "Flight Pilots a Jet", Flight, 1947: 610

- ↑ Gunston 1992, p. 454.

- ↑ Brown 1985, pp. 32–34.

- ↑ "First Jet Landing", Naval Aviation News (United States Navy), March 1946: 6.

- ↑ Brown 1976, pp. 126–7.

- ↑ Brown 1976, pp. 132–6.

- ↑ Jackson 1987, p. 424.

- ↑ "How The Vampires Crossed", Flight, 22 July 1948: 105

- ↑ Dorr 1998, p. 119.

- ↑ Wood, William ‘Bill’ (1997), Only Birds and Fools Fly, UK, retrieved 6 October 2009.

- ↑ Watkins 1996, p. 58.

- ↑ Jackson 1987, pp.429-430

- ↑ "RAAF Museum: RAAF Aircraft Series 2 A79 DHA Vampire". airforce.gov.au.

- ↑ Milberry 1984, p. 212.

- ↑ Milberry 1984, pp. 212, 215.

- ↑ Birtles 1986, p. 37.

- ↑ Birtles 1986, p. 59.

- ↑ Pakistani Air-to-Air Victories, Air Combat Information Group, 2003, retrieved 10 June 2009.

- ↑ http://www.lw.admin.ch/internet/luftwaffe/de/home/themen/history/mittelaus/vampire.html

- ↑ http://www.lw.admin.ch/internet/luftwaffe/de/home/dokumentation/assets/aircraft.parsys.79030.downloadList.74576.DownloadFile.tmp/milkennungen.pdf

- ↑ Thomas 2005, pp. 30, 32.

- ↑ Thomas 2005, pp. 32—5.

- ↑ Thomas 2005, pp. 36—7.

- ↑ Thomas 2005, pp. 39.

- ↑ Brown 1976, p. 130.

- ↑ http://www.warbirdalley.com/vampire.htm

- ↑ http://www.teamvampire.se/english_version.htm

- ↑ "The Aeroplanes".

- ↑ "de Havilland Vampire G-HELV". classicairforce.com.

- ↑ "Vampire Preservation Group - Home Page". vampirepreservation.org.uk.

- ↑ http://www.nzfpm.co.nz/article.asp?id=vampire#

- ↑ Harro Ranter. "ASN Aircraft incident 06-JUN-2009 De Havilland DH.100 Vampire Mk 3 N6878D". aviation-safety.net.

- ↑ http://www.asmac.ab.ca/aerospace/main_collection_details.asp?list_id=8

- ↑ "De Havilland Australia Vampire T.35 (1964)". albertaaviationmuseum.com.

- ↑ "De Havilland D.H.100 Vampire 3 - Canada Aviation and Space Museum". techno-science.ca.

- ↑ "de Havilland DH.100 Vampire FB.6". Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum.

- ↑ "de Havilland Vampire". canadianflight.org.

- ↑ "DH-100 Vampire". comoxairforcemuseum.ca.

- ↑ "Suomen ilmailumuseo - Aircraft". Retrieved 2013-01-25.

- ↑ http://speyer.technik-museum.de/en/en/de-havilland-dh-100-vampire

- ↑ "Volandia: Parco e museo del volo". Retrieved 2015-11-16.

- ↑ "Italian Air Force Museum". Retrieved 2014-05-22.

- ↑ http://www.aviationmuseum.eu/World/Middle-East/Lebanon/Rayak_AFB/Lebanon_Air_Force_Museum.htm

- ↑ "MOTAT Aircraft Collection: De Havilland DH100 Vampire". Retrieved 2014-06-22.

- ↑ "Ohakea gate guardian returns". Stuff.

- ↑ "Air Force Museaum of New Zealand: De Havilland D.H.100 Vampire F.B. Mk.5". Retrieved 2014-06-22.

- ↑ John Austin-Williams (ed.). "de Havilland DH.100 Vampire c/n EP42917 SAAF 208". The de Havilland Aircraft Association of South Africa.

- ↑ John Austin-Williams (ed.). "de Havilland DH.100 Vampire c/n V0581 SAAF 229". The de Havilland Aircraft Association of South Africa.

- ↑ John Austin-Williams (ed.). "de Havilland DH.115 Vampire c/n 15498 ZU-DFH / SAAF 277". The de Havilland Aircraft Association of South Africa.

- 1 2 3 "Midland Air Museum - Explore our Exhibits - Aircraft Listing". midlandairmuseum.co.uk.

- ↑ "Aircraft List". Newark Air Museum. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ↑ "De Havilland Vampire DH115 T11". Yorkshire Air Museum. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ↑ "de Havilland Vampire T11". tangmere-museum.org.uk. 13 May 2015.

- ↑ "Aircraft – de Havilland Aircraft Museum". dehavillandmuseum.co.uk. 16 September 2014.

- ↑ "Wellesbourne Wartime Museum". Aeroflight. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ↑ "Our Aircraft". Norfolk and Suffolk Aviation Museum. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ↑ "Solway Aviation Museum aircraft list". Retrieved 2014-09-18.

- ↑ http://www.nelsam.org.uk/NEAM/Exhibits/History/WZ518.htm

- ↑ "Displays." Montrose Air Station Heritage Centre. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- ↑ Super User. "VAMPIRE". pimaair.org.

- ↑ "Museo Aeronáutico de Maracay". Flickr.

- ↑ Illustrated Encyclopedia of Aircraft 1985, p. 1380.

- 1 2 Jackson 1987, p. 431.

Bibliography

- Bain, Gordon (1992). De Havilland: A Pictorial Tribute. London: AirLife Publishing. ISBN 1-85648-243-X..

- Birtles, Philip (1986). De Havilland Vampire, Venom and Sea Vixen. London: Ian Allen. ISBN 0-7110-1566-X..

- Brown, Eric (1976). "Vampire on a Trampoline". Air Enthusiast Quarterly (Bromley, UK: Fine Scroll) (2): 126–136..

- ——— (January 1985). "Dawn of the Carrier Jet". Air International 28 (1): 31–37. ISSN 0306-5634..

- Buttler, Anthony "Tony" (2000). British Secret Projects: Jet Fighters Since 1950. Leicester, UK: Midland. ISBN 1-85780-095-8..

- Dorr, Robert F (1998). "Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star, Variant Briefing". Wings of Fame: The Journal of Class Combat Aircraft (London: AIRTime Publishing) 11. ISBN 1-86184-017-9..

- Gunston, William "Bill" (1981). Fighters of the Fifties. Cambridge, UK: Patrick Stephens. ISBN 0-85059-463-4..

- ——— (1992). et al. "Vampire Fighters Lead Victory Day fly-by". The Chronicle of Aviation (Liberty, MO: JL). ISBN 1-872031-30-7..

- Harrison, W. A. (2000). De Havilland Vampire. Warpaint series No.27. Buckinghamshire, UK: Hall Park Books. ASIN B001PDL8RK. ISSN 1363-0369.

- Illustrated Encyclopedia of Aircraft (Part Work 1982–1985). London: Orbis Publishing. 1985..

- Jackson, A.J (1987). De Havilland Aircraft since 1909 (3rd ed.). London: Putnam. ISBN 0-85177-802-X..

- Milberry, Lawrence "Larry" (1984). Sixty Years: The RCAF and Air Command 1924–1984. Toronto: Canav Books. ISBN 0-07-549484-1..

- Thomas, Andrew (September–October 2005). "'Booms' Over the 'Bush': De Havilland Vampires in Rhodesian Service". Air Enthusiast (Stamford, UK: Key Publishing) (119): 30–39. ISSN 0143-5450..

- Watkins, David (1996). de Havilland Vampire: The Complete History. Thrupp, Stroud, UK: Budding Books. ISBN 1-84015-023-8..

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to De Havilland Vampire. |

|

| |

|

|

- Manual: (1960) A.P. 4099J-P.N. Pilots Notes Vampire T.11

- Vampire Preservation Group's website

- Autobiography of Bill Wood, who was part of the team that crossed the Atlantic by jet for the first time.

- Norwegian Aviation Museum

- Temora Aviation Museum at Temora, New South Wales, Australia

- Çengelhan Rahmi M. Koç Museum, Ankara, Turkey. An ex-Swiss Air Force FB.6, repainted in RAF colours

- Vampire and Sea Vampire (1946 - 1969)

- Restored RNoAF Vampire FB.52 flying

- "The de Havilland Vampire I (D.H.100)" a 1945 Flight article

- de Havilland Vampire a 1946 Flight advertisement for the Vampire

- 'Flight' Pilots a Jet - a 1947 Flight article on a first flight in a jet powered aircraft

- Vampire J-306 in Chile's Aviation Museum link to Chile's Aviation Museum example of Vampire serial J-306 (in Spanish)

- Vampire T.11, WZ550 Link to the Malta Aviation Museum website

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

|