De Arte Combinatoria

The Dissertatio de arte combinatoria ("Dissertation on the Art of Combinations" or "On the Combinatorial Art") is an early work by Gottfried Leibniz published in 1666 in Leipzig.[1] It is an extended version of his first doctoral dissertation,[2] written before the author had seriously undertaken the study of mathematics.[3] The booklet was reissued without Leibniz' consent in 1690, which prompted him to publish a brief explanatory notice in the Acta Eruditorum.[4] During the following years he repeatedly expressed regrets about its being circulated as he considered it immature.[5] Nevertheless it was a very original work and it provided the author the first glimpse of fame among the scholars of his time.

The main idea behind the text is that of an alphabet of human thought, which is attributed to Descartes. All concepts are nothing but combinations of a relatively small number of simple concepts, just as words are combinations of letters. All truths may be expressed as appropriate combinations of concepts, which can in turn be decomposed into simple ideas, rendering the analysis much easier. Therefore, this alphabet would provide a logic of invention, opposed to that of demonstration which was known so far. Since all sentences are composed of a subject and a predicate, one might

- Find all the predicates which are appropriate to a given subject, or

- Find all the subjects which are convenient to a given predicate.

For this, Leibniz was inspired in the Ars Magna of Ramon Llull, although he criticized this author because of the arbitrariness of his categories and his indexing.

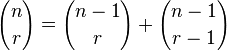

Leibniz discusses in this work some combinatorial concepts. He had read Clavius' comments to the Tractatus de Sphaera of Sacrobosco, and some other contemporary works. He introduced the term variationes ordinis for the permutations, combinationes for the combinations of two elements, con3nationes (shorthand for conternationes) for those of three elements, etc. His general term for combinations was complexions. He found the formula

which he thought was original.

The first examples of use of his ars combinatoria are taken from law, the musical registry of an organ, and the Aristotelian theory of generation of elements from the four primary qualities. But philosophical applications are of greater importance. He cites the idea of Hobbes that all reasoning is just a computation.

The most careful example is taken from geometry, from where we shall give some definitions. He introduces the Class I concepts, which are primitive.

- Class I

- 1 point, 2 space, 3 included, [...] 9 parts, 10 total, [...] 14 number, 15 various [...]

Class II contains simple combinations.

- Class II.1

- Quantity is 14 των 9

Where των means "of the" (from Ancient Greek: τῶν). Thus, "Quantity" is the number of the parts. Class III contains the con3nationes:

- Class III.1

- Interval is 2.3.10

Thus, "Interval" is the space included in total. Of course, concepts deriving from former classes may also be defined.

- Class IV.1

- Line is 1/3 των 2

Where 1/3 means the first concept of class III. Thus, a "line" is the interval of (between) points.

Leibniz compares his system to the Chinese and Egyptian languages, although he did not really understand them at this point. For him, this is a first step towards the Characteristica Universalis, the perfect language which would provide a direct representation of ideas along with a calculus for the philosophical reasoning.

As a preface, the work begins with a proof of the existence of God, cast in geometrical form, and based on the Argument from Motion.

Notes

- ↑ G.W. Leibniz, Dissertatio de arte combinatoria, 1666, Sämtliche Schriften und Briefe (Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1923), A VI 1, p. 163; Philosophische Schriften (Gerhardt) Bd. IV p. 30;

- ↑ The first part of the book was his habilitation thesis in Philosophy at Leipzig University. Leibniz defended his thesis in March 1666 (see Richard T. W. Arthur, Leibniz, John Wiley & Sons, 2014, p. x).

- ↑ Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. Hauptschriften zur Grundlegung der Philosophie. Zur allgemeinen Charakteristik. Philosophische Werke Band 1. p. 32. Translated in German by Artur Buchenau. Published, reviewed and added an introduction and notes by Ernst Cassirer. Hamburg: Felix Meiner, 1966, p. 32.

- ↑ G.G.L. Ars Combinatoria, Acta Eruditorum, Feb. 1691, pp. 63–64

- ↑ Leibniz complained to various correspondents, e.g., to Morell (1 October 1697) or to Meier (23 January 1699); see Akademie I.14, p. 548 or I.16, p. 540.

References

- E.J. Aiton, Leibniz: A Biography. Hilger, Bristol, 1985. ISBN 0-85274-470-6.

External links

- De Arte Combinatoria, the original Latin-language text