Black magic

Black magic or dark magic has traditionally referred to the use of supernatural powers or magic for evil and selfish purposes.[1] With respect to the left-hand path and right-hand path dichotomy, black magic is the malicious, left-hand counterpart of benevolent white magic. In modern times, some find that the definition of "black magic" has been convoluted by people who define magic or ritualistic practices that they disapprove of as "black magic".[2]

History

Like its counterpart white magic, the origins of black magic can be traced to the primitive, ritualistic worship of spirits as outlined in Robert M. Place's 2009 book, Magic and Alchemy.[3] Unlike white magic, in which Place sees parallels with primitive shamanistic efforts to achieve closeness with spiritual beings, the rituals that developed into modern "black magic" were designed to invoke those same spirits to produce beneficial outcomes for the practitioner. Place also provides a broad modern definition of both black and white magic, preferring instead to refer to them as "high magic" (white) and "low magic" (black) based primarily on intentions of the practitioner employing them. He acknowledges, though, that this broader definition (of "high" and "low") suffers from prejudices as good-intentioned folk magic may be considered "low" while ceremonial magic involving expensive or exclusive components may be considered by some as "high magic", regardless of intent.[3][4]

During the Renaissance, many magical practices and rituals were considered evil or irreligious and by extension, "black magic" in the broad sense. Witchcraft and non-mainstream esoteric study were prohibited and targeted by the Inquisition.[5] As a result, natural magic developed as a way for thinkers and intellectuals, like Marsilio Ficino, abbot Johannes Trithemius and Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa, to advance esoteric and ritualistic study (though still often in secret) without significant persecution.[5]

While "natural magic" became popular among the educated and upper classes of the 16th and 17th century, ritualistic magic and folk magic remained subject to persecution. 20th century author Montague Summers generally rejects the definitions of "white" and "black" magic as "contradictory", though he highlights the extent to which magic in general, regardless of intent, was considered "dark" or "black" and cites William Perkins posthumous 1608 instructions in that regard:[6]

All witches "convicted by the Magistrate" should be executed. He allows no exception and under this condemnation fall "all Diviners, Charmers, Jugglers, all Wizards, commonly called wise men or wise women". All those purported "good Witches which do not hurt but good, which do not spoil and destroy, but save and deliver" should come under the extreme sentence.

In particular, though, the term was most commonly reserved for those accused of invoking demons and other evil spirits, those hexing or cursing their neighbours, those using magic to destroy crops and those capable of leaving their earthly bodies and travelling great distances in spirit (to which the Malleus Maleficarum, "devotes one long and important chapter"). Summers also highlights the etymological development of the term nigromancer, in common use from 1200 to approximately 1500, (Latin: Niger, black; Greek: Manteia, divination), broadly "one skilled in the black arts".[6]

In a modern context, the line between "white magic" and "black magic" is somewhat clearer and most modern definitions focus on intent rather than practice.[3] There is also an extent to which many modern Wicca and witchcraft practitioners have sought to distance themselves from those intent on practising black magic. Those who seek to do harm or evil are less likely to be accepted into mainstream Wiccan circles or covens in an era where benevolent magic is increasingly associated with new-age gnosticism and self-help spiritualism.[7]

Satanism and devil-worship

The influence of popular culture has allowed other practices to be drawn in under the broad banner of "black magic" including the concept of Satanism. While the invocation of demons or spirits is an accepted part of black magic, this practice is distinct from the worship or deification of such spiritual beings.[7]

Those lines, though, continue to be blurred by the inclusion of spirit rituals from otherwise "white magicians" in compilations of work related to Satanism. John Dee's 16th century rituals, for example, were included in Anton LaVey's The Satanic Bible (1969) and so some of his practises, otherwise considered white magic, have since been associated with black magic. Dee's rituals themselves were designed to contact spirits in general and angels in particular, which he claimed to have been able to do with the assistance of colleague Edward Kelley. LaVey's Bible, however, is a "complete contradiction" of Dee's intentions but offers the same rituals as a means of contact with evil spirits and demons.[8] Interestingly, LaVey's Church of Satan (with LaVey's Bible at its centre), "officially denies the efficacy of occult ritual" but "affirms the subjective, psychological value of ritual practice", drawing a clear distinction between.[8] LaVey himself was more specific:

White magic is supposedly utilized only for good or unselfish purposes, and black magic, we are told, is used only for selfish or "evil" reasons. Satanism draws no such dividing line. Magic is magic, be it used to help or hinder. The Satanist, being the magician, should have the ability to decide what is just, and then apply the powers of magic to attain his goals.

Satanism is not a white light religion; it is a religion of the flesh, the mundane, the carnal - all of which are ruled by Satan, the personification of the Left Hand Path.

The latter quote, though, seems to have been directed toward the growing trends of Wiccanism and neo-paganism at the time.[8]

Voodoo

Voodoo, too, has been associated with modern "black magic"; drawn together in popular culture and fiction. However, while hexing or cursing may be accepted black magic practices, Voodoo has its own distinct history and traditions that have little to do with the traditions of modern witchcraft that developed with European practitioners like Gerald Gardner and Aleister Crowley.[7][9][10]

In fact, Voodoo tradition makes its own distinction between black and white magic, with sorcerers like the Bokor known for using magic and rituals of both. But their penchant for magic associated with curses, poisons and zombies means they, and Voodoo in general, are regularly associated with black magic in particular.[11]

Black magic and religion

The links and interaction between black magic and religion are many and varied. Beyond black magic's links to organised Satanism or its historical persecution by Christianity and its inquisitions, there are links between religious and black magic rituals. The Black Mass, for example, is a sacrilegious parody of the Catholic Mass. Likewise, a saining, though primarily a practice of white magic, is a Wiccan ritual analogous to a christening or baptism for an infant.[12][13]

17th century priest, Étienne Guibourg, is said to have performed a series of Black Mass rituals with alleged witch Catherine Monvoisin for Madame de Montespan.[14]

In Islam, al-Falaq is recited to protect against sorcery.

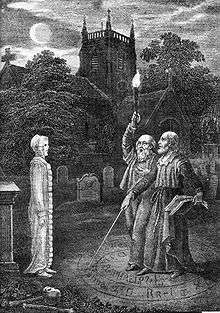

Practices and rituals

The lowest depths of black mysticism are well-nigh

as difficult to plumb as it is arduous to scale

the heights of sanctity. The Grand Masters of

the witch covens are men of genius - a foul genius,

crooked, distorted, disturbed, and diseased.

Witchcraft and Black Magic

During his period of scholarship, A. E. Waite provided a comprehensive account of black magic practices, rituals and traditions in The Book of Black Magic and Ceremonial Magic.[15] Other practitioners have expanded on these ideas and offered their own comprehensive lists of rituals and concepts. Black magic practices and rituals include:

- True name spells - the theory that knowing a person's true name allows control over that person, making this wrong for the same reason. This can also be used as a connection to the other person, or to free them from another's compulsion, so it is in the grey area.

- Immortality rituals - from a Taoist perspective, life is finite, and wishing to live beyond one's natural span is not with the flow of nature. Beyond this, there is a major issue with immortality. Because of the need to test the results, the subjects must be killed. Even a spell to extend life may not be entirely good, especially if it draws life energy from another to sustain the spell.[16]

- Necromancy - for purposes of usage, this is defined not as general black magic, but as any magic having to do with death itself, either through divination of entrails, or the act of raising the dead body, as opposed to resurrection or CPR.[17]

- Curses and hexes - a curse can be as simple as wishing something bad would happen to another, through a complex ritual.[18]

In popular culture and fiction

Concepts related to black magic or described, even inaccurately, as "black magic" are a regular feature of books, films and other popular culture. Examples include:

- Black Magic (Little Mix song) - Lead single by British girl-group Little Mix released in May 2015, for their third studio album "Get Weird".

- The Devil Rides Out - a 1934 novel by Dennis Wheatley - made into a famous film by Hammer Studios in 1968

- Rosemary's Baby - a 1968 horror novel in which black magic is a central theme.

- The Craft - a 1996 film featuring four friends who become involved in white witchcraft but turn to black magic rituals for personal gain.

- The Harry Potter series - black magic, including various spells and curses, is referred to as "the dark arts" against which students are taught to defend themselves.

- Final Fantasy - a video game in which white and black magic are simply used to distinguish between healing/defensive spells (such as a "cure") and offensive/elemental spells (such as "fire") and do not carry an inherent good or evil connotation.

- Charmed - a television series in which black magic is also known as "the black arts", "dark arts", "dark magic" or even "evil magic", and is used by demons and other evil beings.

- The Secret Circle - A short-lived television series featuring witches, in which there are two kinds of magic. While traditional magic helps you to connect to the energy around you, more lethal and dangerous dark magic is rooted in the anger, fear and negativity inside you. Only a few born with it can access dark magic and some are inherently stronger than others.

- The Power of Five is an entire series by Anthony Horowitz about black magic and evil sorcerers. The antagonists are all black sorcerers and are all practitioners of black magic, black magic is a means of summoning the Old Ones from their prison, Hell. Black magic often takes the form of mass murder and animation of inanimate objects.

- Night Watch - In the Night Watch book (and movie) series the magicians are grouped into two sides "Light Others" and "Dark Others". The dark magicians are more motivated by selfish desires.

- Supernatural (U.S. TV series) - The television series Supernatural features many events and characters that feature and participate in black magic.

- The Hobbit (film series) - The films based on J. R. R. Tolkien's book The Hobbit feature elements of black magic centered around a character known as "the Necromancer", however this is very seldom mentioned in the book. It later is discovered that the Necromancer is Sauron who is the principle dark character of the whole Lord of the Rings series.

- The Lord of the Rings - The Lord of the Rings' essential antagonist is Sauron. Sauron and his followers use black magic on many events such as the creation of many of his followers and the forging of the One Ring.

- Sherlock Holmes (2009 film) - The first of the two Sherlock Holmes films directed by Guy Ritchie includes elements of black magic although they are later discovered to be false.

- Versailles (band) released a short film in 2009 which depicted zombies that were resurrected by Jasmine You through black magic.

- Smith Chart -The term is often used to refer to the field of RF or microwave engineering.

See also

- Demonology

- Gray magic

- Left-hand path and right-hand path

- Magical texts

- Maleficium (sorcery)

- Necromancy

- Seiðr

- Ya sang

References

- ↑ J. Gordon Melton, ed. (2001). "Black Magic". Encyclopedia of Occultism & Parapsychology. Vol 1: A–L (Fifth ed.). Gale Research Inc. ISBN 0-8103-9488-X.

- ↑ Jesper Aagaard Petersen (2009). Contemporary religious Satanism: A Critical Anthology. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 220. ISBN 0-7546-5286-6.

- 1 2 3 Magic and Alchemy by Robert M. Place (Infobase Publishing, 2009)

- ↑ Evans-Pritchard. "Sorcery and Native Opinion". Africa: Journal of the International African Institute Vol. 4, No. 1 (Jan., 1931) , pp. 22-55.

- 1 2 White Magic, Black Magic in the European Renaissance by Paola Zambelli (BRILL, 2007)

- 1 2 Witchcraft and Black Magic by Montague Summers (1946; reprint Courier Dover Publications, 2000)

- 1 2 3 Magical Religion and Modern Witchcraft by James R. Lewis (SUNY Press, 1996)

- 1 2 3 Modern Satanism: Anatomy of a Radical Subculture by Chris Mathews (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2009)

- ↑ "Voodoo 2.0." Newsweek Global 163.9 (2014): 92-98. Academic Search Complete. Web. 19 Feb. 2015.

- ↑ Long, Carolyn Morrow. "Perceptions of New Orleans Voodoo: Sin, Fraud, Entertainment, and Religion". Nova Religion: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions, Vol. 6, No. 1 (October 2002), pp. 86-101

- ↑ Voodoo Rituals: A User's Guide by Heike Owusu (Sterling Publishing Company, 2002)

- ↑ "Black Mass." Funk & Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia (2014): 1p. 1. Funk & Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia. Web. 11 Feb. 2015.

- ↑ Macmullen, Ramsay, and Eugene Lane. "From Black Magic To Mystical Awe." Christian History 17.1 (1998): 37. History Reference Center. Web. 19 Feb. 2015.

- ↑ Geography of Witchcraft by Montague Summers (1927; reprint Kessinger Publishing, 2003)

- ↑ The Book of Black Magic and Ceremonial Magic by Arthur Edward Waite (1911; reprint 2006)

- ↑ "Immortality." Funk & Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia (2014): 1p. 1. Funk & Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia. Web. 11 Feb. 2015.

- ↑ "necromancy". Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary (11th ed.). Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster. April 2008.

- ↑ "Hex." Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 6Th Edition (2013): 1. Literary Reference Center. Web. 11 Feb. 2015.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||