Deutscher Fernsehfunk

.svg.png) | |

| Type | Broadcast television |

|---|---|

| Country | East Germany |

| Availability | Free-to-air Analogue terrestrial |

Broadcast area |

East Germany and parts of West Germany Czechoslovakia Poland |

| Owner | Government of East Germany |

Launch date | 21 December 1952 |

| Dissolved | 31 December 1991 |

Former names | Fernsehen der DDR (February 1972 – February 1990) |

| Replaced by |

DFF 1: expansion of Das Erste on 15 December 1990 DFF 2: replaced by DFF Länderkette on 15 December 1990 DFF Länderkette: replaced by MDR Fernsehen in Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, Thuringia, Fernsehen Brandenburg in Brandenburg and expansion of N3 in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern on 1 January 1992 |

Deutscher Fernsehfunk (DFF), known from 1972 to 1990 as Fernsehen der DDR (DDR-FS), was the state television broadcaster in East Germany.

History

Foundation

Radio was the dominant medium in the former Eastern bloc, with television being considered low on the priority list when compiling Five-Year Plans during the industrialisation of the 1950s. In Germany, the situation was different as East and West Germany were in competition over available frequencies for broadcasts and for viewers across the Iron Curtain. The West German Nordwestdeutscher Rundfunk (NWDR) had made early plans to begin television broadcasts in its area, which originally included West Berlin. The first western test broadcasts were made in 1950.

The GDR authorities therefore also made an early start with television and began construction of a television centre in Adlershof on 11 June 1950. The GDR television service began experimental test broadcasts on 20 December 1951. The NWDR announced plans to begin a regular television service from Hamburg starting with Christmas 1952. This spurred the East German authorities into further action.

A relay transmitter in the centre of East Berlin was built in February 1952 and connected to Adlershof on 3 June. On 16 November, the first television sets were made available to the public at 3500 East German marks each.

Regular public programming, although still described as testing, began on 21 December 1952 – Joseph Stalin's birthday – with two hours a day of programmes. Continuity announcer Margit Schaumäker welcomed viewers at 20:00 and introduced the station's logo – the Brandenburg Gate. Speeches by senior figures in the television organisation followed, then the first edition of the East German national news programme, Aktuelle Kamera, presented by Herbert Köfer.

The policy of the ruling Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED) was to censor the "mass media". As television had a limited audience, it was not classed as a mass medium and therefore Aktuelle Kamera was, at first, uncensored and even critical. This situation changed after the television service reported accurately on the uprising in East Germany on 17 June 1953, prompting the director's removal. From then on, television newscasts took on a similar character to their radio counterparts, and were sourced from official outlets.

Growth

Once television was established, the transmitter network grew quickly.

- 1953 Berlin-Grünau

- 1954 Berlin-Müggelberg (not completed); Dresden.

- 1955 Berlin-Mitte, Brocken, Inselsberg (Brocken and Inselsberg had a large footprint in West Germany), Helpterberg, Marlow, Chemnitz

- 1956 Berlin-Köpenick

Technology and TV studios also extended quickly. In the summer of 1953, Studio I was opened at Adlershof. In 1955 the first mobile transmission unit and a third broadcasting studio were added to the system.

On 2 January 1956 the "official test program" of the television centre in Berlin ended, and on 3 January the national Deutscher Fernsehfunk (German Television Broadcasting – DFF) began transmitting.[1]

The new television service was deliberately not called "GDR Television", as the intention was to provide an all-German service, as was the case with the west. However, the geography of Germany prevented this – despite placing high-power transmitters in border areas, the GDR could not penetrate the entirety of West Germany. In contrast, West German broadcasts (particularly ARD) easily reached most of East Germany except for the extreme south-east (most notably Dresden, the area being in a deep valley, leading to its old East German nickname of "Tal der Ahnungslosen", or "Valley of the Clueless") and the extreme north-east (around Rügen, Greifswald, Neubrandenburg and beyond).

By the end of 1958, there were over 300,000 television sets in the GDR.

News and political programming on DFF was usually scheduled not to clash with similar programming on Western channels (as most viewers would probably have preferred the western programmes). For example, the main news program, Aktuelle Kamera, was scheduled at 19:30, between ZDF's heute at 19:00 and ARD's Tagesschau at 20:00. However, popular entertainment programming (such as Ein Kessel Buntes) was scheduled to clash with Western news or current affairs programmes in the hope of discouraging viewers from watching the Western programmes. Other popular items (such as films) were scheduled before or after propaganda programmes like Der schwarze Kanal in the hope that viewers tuning in early to catch the film would see the programme.

From 7 October 1958, DFF introduced morning programmes – repeats of the previous night's programming for shift workers, broadcast under the title "Wir wiederholen für Spätarbeiter" ("We repeat for late workers").

DFF/DDR-FS produced a number of educational programmes for use in schools, including programmes on chemistry, history, local history and geography, literature, physics, civics, and Russian. Also produced was "ESP": Einführung in die sozialistische Produktion ("An introduction to Socialist production") and an English-learners course, English for You. Many of these programmes are archived and are available from the DRA in Babelsberg.

The Berlin Wall

After the construction of the Berlin Wall in August 1961, the GDR began a programme to attempt to prevent its citizens from watching West German broadcasts. The GDR had its diplomatic hands tied: jamming the broadcasts with any degree of effectiveness would also interfere with reception within West Germany (breaching treaties and inviting retaliation). Instead, the Free German Youth, Freie Deutsche Jugend (FDJ), the official youth movement in the GDR, started the campaign "Blitz contra Natosender" – "Strike against NATO's stations" – to encourage young people to remove or damage aerials pointing at the west. The term Republikfluchtigen (defection by television) was sometimes used to describe the widespread practice of viewing Westfernsehen (Western TV). Nevertheless, people continued to watch ARD broadcasts, leading to Der schwarze Kanal.[2]

Colour and DFF2

Colour television was introduced on 3 October 1969 on the new channel DFF2, which commenced broadcasting the same day, ready for the celebrations for the 20th anniversary of the founding of the GDR on 7 October. DFF chose the French SÉCAM colour standard, common in the Eastern Bloc, while West Germany had settled on the PAL standard. Mutual reception in black and white remained possible as the basic television standard was the same. Colour sets were at first not widely available in the East and many of these were modified to receive PAL as well as SÉCAM. East German manufacturers later made dual standard sets.

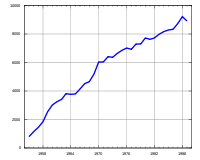

The introduction of DFF2 marked an increase in the hours of broadcasting overall.

| Year | 1955 | 1960 | 1965 | 1970 | 1975 | 1980 | 1985 | 1988 | 1989 |

| Hours broadcast per year | 786 | 3007 | 3774 | 6028 | 6851 | 7704 | 8265 | 9194 | 8900 |

| Hours broadcast per week | 15 | 58 | 73 | 116 | 132 | 148 | 159 | 177 | 171 |

On 11 February 1972, the DFF was renamed, dropping the pretense of being an all-German service and becoming Fernsehen der DDR – GDR Television or DDR-FS. The previous name survived in episodes of The Sandman, which were repeated quite often.

Since DFF2/DDR-F2 only broadcast in the evening for most of its lifespan, special transmissions could easily be made in the afternoon for special events.[1]

1980 Olympic Games

The hosting of the 1980 Summer Olympics by Moscow was a source of pride for the Eastern Bloc. However, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 had caused outrage in the west, leading to a boycott of the games by 64 western-aligned nations.

DDR-FS therefore wished to present colour pictures of the games to West Germany, which was part of the boycott, and a programme of experimental transmissions in PAL was instituted. However, little came of these experiments. By 1985 there were 6,078,500 licensed televisions, or 36.5 for every 100 persons.

Gorizont: satellite television

In 1988, the USSR-built Gorizont satellite was launched, providing television programming to much of Europe and northern Africa, and even eastern parts of the Americas. The programmes of all the Eastern European socialist republics, including DDR-F1, were broadcast on the satellite.

Collapse of the GDR

In 1989, the GDR made an attempt to bring its young people closer to the state and distract them from the media of the West. A new young-person's programme, Elf 99 (1199 being the postal code of the Adlershof studios) was created as part of this plan.

However, the plan was not successful as the GDR itself began to dissolve under economic and popular political pressure brought about by the reforms in Moscow under Mikhail Gorbachev.

At first, DDR-FS stuck to the party line and barely reported the mass protests in the country. However, after Erich Honecker was removed from office on 18 October 1989 and the rule of the SED began to break down, DDR-FS reformed their programmes to remove propaganda and to report news freely. The main propaganda programme, Der schwarze Kanal (The Black Channel) – which ran West German TV news items with an explanatory commentary informing viewers of the "real" stories and meanings behind the pictures and generally criticising Western media (Particularly ARD and ZDF) – stopped on 30 October 1989.

By the time the borders opened on 9 November, the main news programme on DDR2 was being produced without censorship or interference, and so it covered the events in full. In recognition of its reliable coverage, the programme was re-broadcast on the West German channel 3sat. DDR-FS joined the 3sat consortium in February 1990. DDR-FS became almost completely separate from the state apparatus, starting a number of new programme strands, including a free and open debate programme on Thursdays, complete with critical phone-in contributions from viewers. At first this had to be handled very carefully, as the Stasi – the state secret police – were still operating and had an office in the studios.

In February 1990, the Volkskammer passed a media resolution defining DDR-FS as a politically independent public broadcasting system. A law passed by the Volkskammer in September 1990 made this a legal requirement. On 4 March 1990, emphasising the change and reflecting the forthcoming reunification, DDR1 and DDR2 were renamed back to DFF1 and DFF2.

Reunification

Upon reunification on 3 October 1990, the DFF ceased to be the state broadcaster of the former GDR. Because the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany reserves broadcasting as a matter for the German states (Länder), the Federal Government was not permitted to continue to run a broadcasting service. Article 36 of the Unification Treaty (Einigungsvertrag) between the two German states (signed on 31 August 1990) required that DFF was to be dissolved by 31 December 1991 and that the former West German television broadcasting system be extended to replace it.

On 15 December 1990, the ARD's Das Erste channel took over the frequencies of DFF1. Das Erste had regional opt-outs during the first part of the evening, but the former GDR did not have ARD broadcasters to fill these spaces. Therefore, DFF continued to provide programmes until 31 December 1991 in these slots:

- Landesschau for Brandenburg (originally LSB aktuell)

- Nordmagazin for Mecklenburg-Vorpommern

- Tagesbilder for Saxony-Anhalt

- Bei uns in Sachsen for Saxony

- Thüringen Journal for Thuringia

Successors

The dissolution of DFF and its replacement by Länder-based ARD broadcasters remained controversial throughout the process.

Employees of the DFF were worried about job prospects in the new broadcasters and also had a loyalty to the DFF. Viewers, accustomed to the DFF's programming, were concerned at the loss of favourite shows and the choice most viewers had between West and East channels. The new Länder considered keeping a form of DFF running as the equivalent to the ARD members' "third programme" in other regions. However, political opinion was against centralisation and in favour of the new devolved system brought in from the west.

Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Thuringia agreed to pool their broadcasts into Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk (MDR), an ARD member broadcaster based in Leipzig. Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Brandenburg, and Berlin considered pooling their broadcasts into Nordostdeutschen Rundfunkanstalt – Northeast German Broadcasting (NORA). Another alternative was for Brandenburg and Berlin to consolidate and for Mecklenburg-Vorpommern to have its own broadcaster.

No agreement could be reached between the three Länder; Mecklenburg therefore joined the existing Norddeutscher Rundfunk (NDR), while the existing Sender Freies Berlin (SFB) expanded to the whole of the city and a new broadcaster, Ostdeutscher Rundfunk Brandenburg (ORB) was launched for Brandenburg.

DFF finally ended on 31 December 1991. The new organisations began transmissions the next day, on 1 January 1992. On 1 May 2003, SFB and ORB merged to form Rundfunk Berlin-Brandenburg (RBB).

Programmes

- Aktuelle Kamera: The main news programme.

- Brummkreisel: Children's programme.

- Der schwarze Kanal: Propaganda programme. This programme took West German news reports (which were widely viewed by the people) and had a journalist comment on their "real" meanings, which were, of course, in line with the views of the East German government.

- Ein Kessel Buntes: Bi-monthly popular entertainment show.

- Mach mit, Machs Nach, Machs besser: Youth programme.

- Prisma: Current affairs programme hosted by Axel Kaspar

- Rumpelkammer: popular entertainment hosted by Willi Schwabe

- Das Spielhaus: children's puppet theatre programme

The Monday evening feature film (usually an entertainment movie from the 1930s/40s) was one of the more popular items on DFF.

Sandmännchen

On 8 October 1958, DFF imported Sandmännchen (the little Sandman) from radio. Both East and West television ran versions of this idea: an animated film that told a children's story and then and sent them to bed before the programmes for adults began at 19:00. With several generations of children growing up with the Sandman, it has remained a popular childhood memory.

The West version was discontinued by the ARD upon reunification; however, stations in the former GDR continued to play clips from the East's Sandman every night, and RBB still continues the practice as does KIKA. The character plays an important background role in the popular 2003 tragicomedy film Good Bye Lenin!, symbolising the feelings of loss of the main character played by Daniel Brühl.

List of names

- 21 December 1952 – 11 February 1972: Deutscher Fernsehfunk (DFF)

- 3 October 1969 – 11 February 1972: Deutscher Fernsehfunk I (DFF1) and Deutscher Fernsehfunk II (DFF2)

- 11 February 1972 – 4 March 1990: Fernsehen der DDR (DDR-FS)

- 11 February 1972 – April 1976?: TV1 DDR (TV1) and TV2 DDR (TV2)

- April 1976? – 1989: DDR-F1 and DDR-F2

- 1989 – 4 March 1990: Fernsehen der DDR 1. (DDR-F1) and Fernsehen der DDR 2. (DDR-F2)

- 4 March 1990 – 15 December 1990: Deutscher Fernsehfunk

- 4 March 1990 – 15 December 1990: Deutscher Fernsehfunk 1 (DFF 1) and Deutscher Fernsehfunk 2 (DFF 2)

- 15 December 1990 – 31 December 1991: DFF Länderkette

Directors of DFF/DDR-FS

- 1950–1952 Hans Mahle (Director-general)

- 1952–1953 Hermann Zilles (Director)

- 1954–1989 Heinz Adameck (Director)

- 1989–1990 Hans Bentzien (Director-general)

- 1990–1991 Michael Albrecht (Director)

Technical information

Broadcast system

When television broadcasting started, the GDR chose to use the Western European B/G transmission system rather than the Eastern European D/K system, in order to keep transmissions compatible with West Germany. Of course, this made East German television incompatible with the other Eastern Bloc countries, although the D/K system was used prior to 1957.

Irregular channels

Although DFF decided to revert to Western Europe's standard, the first broadcasts used a set of seven VHF channels some of which were not in line with any other system at the time.[3]

| Channel | Channel Limits (MHz) | Vision Carrier (MHz) | Main Sound Carrier (5.5 MHz) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 58.00 – 65.00 | 59.25 | 64.75 | Overlapped western Channels E3 (54–61 MHz) and E4 (61–68 MHz) Vision carrier identical to OIRT channel R2 |

| 2 | 144.00 – 151.00 | 145.25 | 150.75 | Overlapped 2-meter band (144–148 MHz) |

| 3 | 154.00 – 161.00 | 155.25 | 160.75 | Overlapped Marine VHF radio band (156–174 MHz) |

| 5 | 174.00 – 181.00 | 175.25 | 180.75 | Identical to western Channel E5 |

| 6 | 181.00 – 188.00 | 182.25 | 187.75 | Identical to western Channel E6 |

| 8 | 195.00 – 202.00 | 196.25 | 201.75 | Identical to western Channel E8 |

| 11 | 216.00 – 223.00 | 217.25 | 222.75 | Identical to western Channel E11 |

Eventually (around 1960), the channels standard to Western Europe were adopted.[4]

In what may have been attempt to frustrate reception (in some areas) of ARD some early TV sets manufactured in the GDR only tuned the seven channels used by DFF (rather than the full set of 11 VHF channels). Later (following the launch of the second network) UHF tuners were added but early versions only covered the lower part of the band.

Colour

When colour television was introduced, the SÉCAM system was chosen rather than the West German PAL. The incompatibilities between the two colour systems are minor, allowing for pictures to be watched in monochrome on non-compatible sets. Most East German television receivers were monochrome and colour sets usually had after-market PAL modules fitted to allow colour reception of West German programmes; the official sale of dual standard sets in East Germany started in December 1977. The same applied in West Germany. There were experimental PAL broadcasts most notably during the 1980 Moscow Olympics (which got little coverage on West German television due to the boycott).

With reunification, it was decided to switch to the PAL colour system. The system was changed between the end of DFF programmes on 14 December 1990 and the opening of ARD programmes on 15 December. The transmission authorities made the assumption that most East Germans had either dual standard or monochrome sets; those who did not could purchase decoders.

Technical innovations

DDR-FS was the first television broadcaster in Germany to introduce the Betacam magnetic recording system. Betacam was later adopted by all German broadcasters and is still in use by ARD and ZDF.

In 1983 DDR-FS also pioneered the use of Steadicam equipment for live reporting.

Finance

Broadcasting in the GDR was financed by a compulsory licence fee. An annual fee of 10.50 Ostmarks was charged for a joint television and radio licence. A separate radio or car radio licence cost between 0.50 and 2 Ostmarks. (At one time, there was a slightly lower rate for viewers not equipped with the UHF aerials necessary to receive the second channel, however, this arrangement was seen as impractical and abandoned)

In addition, broadcasting was heavily subsidised by the state. For example, in 1982, the GDR realized revenues of 115.4 million Ostmarks through licence fees, while the amount budgeted in 1983 for the television service alone was 222 million Ostmarks.

Advertising

Advertising – in the form of "commercial" magazine programmes – had appeared on GDR television from 1959. However, in a command economy, there was little or no competition between brands, so advertising was limited to informing viewers what products were available. By 1975, the advertising magazines gave up the pretence of being western-style commercial programmes and converted to being "shoppers guides", listing availability and prices of goods.

With the end of the Communist system, spot advertising was introduced to DFF in order to better cover the system's cost. The French advertising agency Information et Publicité was engaged to produce and sell commercials and airtime on the DFF networks.

Archives

The archives of the GDR radio and television stations are administered by German Broadcasting Archive (Deutsches Rundfunkarchiv – DRA) at Babelsberg in Potsdam.

See also

References

- For further information see: Deutscher Fernsehfunk (German) and Rundfunk der DDR (German).

The following are the sources for that article and are, therefore, in German.

- Thomas Beutelschmidt: "Alles zum Wohle des Volkes?!?" Die DDR als Bildschirm-Wirklichkeit vor und nach 1989, 1999 (PDF file)

- Lars Brücher: Das Westfernsehen und der revolutionäre Umbruch in der DDR im Herbst 1989, Magisterarbeit, 2000 ()

- Peter Hoff: Kalter Krieg auf deutschen Bildschirmen – Der Ätherkrieg und die Pläne zum Aufbau eines zweiten Fernsehprogramms der DDR, In: Kulturation, Ausgabe 2, 2003. ISSN 1610-8329 ()

- Hans Müncheberg: Ein Bayer bläst die Lichtlein aus – Ost-Fernsehen im Wendefieber und Einheitssog, In: Freitag 46/2004, Berlin, 2004 ISSN 0945-2095 ()

- Hans Müncheberg: Blaues Wunder aus Adlershof. Der Deutsche Fernsehfunk – Erlebtes und Gesammeltes. Berlin: Das Neue Berlin Verlagsgesellschaft mbH, 2000. ISBN 3-360-00924-X

- Christina Oberst-Hundt: Vom Aufbruch zur Abwicklung – Der 3. Oktober 1990 war für den Rundfunk der DDR die Beendigung eines Anfang, In: M – Menschen Machen Medien, 2000 ISSN 0946-1132 ()

- Markus Rotenburg: Was blieb vom Deutschen Fernsehfunk? Fernsehen und Hörfunk der DDR 15 Jahre nach dem Mauerfall. Brilon, Sauerland Welle, gesendet am 9. und 16. November 2004.

- Sabine Salhoff (Bearb.): Das Schriftgut des DDR-Fernsehens. Eine Bestandsübersicht. Potsdam-Babelsberg: DRA, 2001. ISBN 3-926072-98-9

- Erich Selbmann: DFF Adlershof. Wege übers Fernsehland. Berlin: Edition Ost, 1998. ISBN 3-932180-52-6 (Selbmann was from 1966 to 1978 the producer of Aktuelle Kamera.) –

- Eine Darstellung der Entwicklung des Fernsehens aus dem "anderen" Deutschland – der DDR

Additional sources

These sources are in English and were used to clarify or extend the translation.

- Hancock, Dafydd Fade to black Intertel from Transdiffusion, 2001; accessed 19 February 2006. (English)

- Tust, Dirk Germany (1980s) Intertel from Transdiffusion, 2003; accessed 19 February 2006. (English)

- Paulu, Burton Broadcasting on the European Continent Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press 1967 (English)

External links

- Deutsches Rundfunkarchiv (German)

- Research on the History of Television Programs of the GDR (German)

- http://home.arcor.de/madeingdr/gdrsite/tv/index2_(2).htm (German) Details of TV programmes

- http://www.scheida.at/scheida/Televisionen_DDR.htm (German) Article about reception/Technical issues

Coordinates: 52°25′55″N 13°32′24″E / 52.432°N 13.540°E

|