Daniel O'Connell

| Daniel O'Connell Dónall Ó Conaill | |

|---|---|

O'Connell, in an 1836 painting by Bernard Mulrenin. | |

| Member of Parliament for Clare | |

|

In office 5 July 1828 – 29 July 1830 | |

| Preceded by | William Vesey-FitzGerald |

| Succeeded by | William Macnamara |

| Member of Parliament for Dublin City | |

|

In office 22 December 1832 – 16 May 1836 | |

| Preceded by | Sir Frederick Shaw |

| Succeeded by | George Hamilton |

| Member of Parliament for Dublin City | |

|

In office 5 August 1837 – 10 July 1841 | |

| Preceded by | George Hamilton |

| Succeeded by | John West |

| Lord Mayor of Dublin | |

|

In office 1841–1842 | |

| Preceded by | Sir John James, 1st Baronet |

| Succeeded by | George Roe |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

6 August 1775 Cahersiveen, County Kerry, Ireland |

| Died |

15 May 1847 (aged 71) Genoa, Kingdom of Sardinia |

| Resting place | Glasnevin Cemetery, Dublin |

| Political party | |

| Spouse(s) | Mary O'Connell (m.1802) |

| Children | |

| Alma mater |

Lincoln's Inn King's Inns |

| Occupation | Barrister, political activist |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

| Signature |

|

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch | Yeomanry |

| Years of service | 1797 |

| Unit | Lawyer's Artillery Corps |

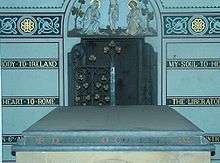

Daniel O'Connell (Irish: Dónall Ó Conaill; 6 August 1775 – 15 May 1847), often referred to as The Liberator[1] or The Emancipator,[2] was an Irish political leader in the first half of the 19th century. He campaigned for Catholic emancipation—including the right for Catholics to sit in the Westminster Parliament, denied for over 100 years—and repeal of the Act of Union which combined Great Britain and Ireland.

Early life

O'Connell was born at Carhan near Cahersiveen, County Kerry, to the O'Connells of Derrynane, a once-wealthy Roman Catholic family, that had been dispossessed of its lands. Among his uncles was Daniel Charles, Count O'Connell, an officer in the Irish Brigades of the French Army. A famous aunt was Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill, while Sir James O'Connell, 1st Baronet, was his younger brother. Under the patronage of his wealthy bachelor uncle Maurice "Hunting Cap" O'Connell, he studied at Douai in France and was admitted as a barrister to Lincoln's Inn in 1794, transferring to Dublin's King's Inns two years later. In his early years, he became acquainted with the pro-democracy radicals of the time and committed himself to bringing equal rights and religious tolerance to his own country.[3]

While in Dublin studying for the law, O'Connell was under his Uncle Maurice's instructions not to become involved in any militia activity. When Wolfe Tone's French invasion fleet entered Bantry Bay in December 1796, O'Connell found himself in a quandary. Politics was the cause of his unsettlement.[4] Dennis Gwynn in his Daniel O'Connell: The Irish Liberator suggests that the unsettlement was because he was enrolled as a volunteer in defence of Government, yet the Government was intensifying its persecution of the Catholic people—of which he was one.[4] He desired to enter Parliament, yet every allowance that the Catholics had been led to anticipate, two years previously, was now flatly vetoed.[4]

As a law student, O'Connell was aware of his own talents, but the higher ranks of the Bar were closed to him. He read the Jockey Club as a picture of the governing class in England and was persuaded by it that, "vice reigns triumphant in the English court at this day. The spirit of liberty shrinks to protect property from the attacks of French innovators. The corrupt higher orders tremble for their vicious enjoyments."[4]

O'Connell's studies at the time had concentrated upon the legal and political history of Ireland, and the debates of the Historical Society concerned the records of governments, and from this he was to conclude, according to one of his biographers, "in Ireland the whole policy of the Government was to repress the people and to maintain the ascendancy of a privileged and corrupt minority."[4]

On 3 January 1797, in an atmosphere of alarm over the French invasion fleet in Bantry Bay, he wrote to his uncle saying that he was the last of his colleagues to join a volunteer corps and 'being young, active, healthy and single' he could offer no plausible excuse.[5] Later that month, for the sake of expediency, he joined the Lawyer's Artillery Corps.[6]

On 19 May 1798, O'Connell was called to the Irish Bar and became a barrister. Four days later, the United Irishmen staged their rebellion which was put down by the British with great bloodshed. O'Connell did not support the rebellion; he believed that the Irish would have to assert themselves politically rather than by force.

He went on the Munster circuit, and for over a decade, he went into a fairly quiet period of private law practice in the south of Ireland.[3] He was reputed to have the largest income of any Irish barrister but, due to natural extravagance and a growing family, was usually in debt- his brother remarked caustically that Daniel was in debt all his life from the age of seventeen. Although he was ultimately to inherit Derrynane from his uncle Maurice, the old man lived to be almost 100 and in the event Daniel's inheritance did not cover his debts.

He also condemned Robert Emmet's Rebellion of 1803. Of Emmet, a Protestant, he wrote: 'A man who could coolly prepare so much bloodshed, so many murders—and such horrors of every kind has ceased to be an object of compassion.'[7]

Despite his opposition to the use of violence, he was willing to defend those accused of political crimes, particularly if he suspected that they had been falsely accused, as in the Doneraile conspiracy trials of 1829, his last notable Court appearance. He was noted for his fearlessness in Court: if he thought poorly of a judge (as was very often the case) he had no hesitation in making this clear. Most famous perhaps was his retort to Baron McClelland, who had said that as a barrister he would never have taken the course O'Connell had adopted: O'Connell said that McClelland had never been his model as a barrister, neither would he take directions from him as a judge.[8] He did not lack the ambition to become a judge himself: in particular he was attracted by the position of Master of the Rolls in Ireland, yet although he was offered it more than once, finally refused.

Campaigning for Catholic emancipation

O'Connell returned to politics in the 1810s. In 1811, he established the Catholic Board, which campaigned for Catholic emancipation, that is, the opportunity for Irish Catholics to become members of parliament. In 1823, he set up the Catholic Association which embraced other aims to better Irish Catholics, such as: electoral reform, reform of the Church of Ireland, tenants' rights, and economic development.[9]

The Association was funded by membership dues of one penny per month, a minimal amount designed to attract Catholic peasants. The subscription was highly successful, and the Association raised a large sum of money in its first year. The money was used to campaign for Catholic emancipation, specifically funding pro-emancipation members of parliament (MPs) standing for the British House of Commons.[10]

.jpg)

Members of the Association were liable to prosecution under an eighteenth-century statute, and the Crown moved to suppress the Association by a series of prosecutions, with mixed success. O'Connell was often briefed for the defence, and showed extraordinary vigour in pleading the rights of Catholics to argue for emancipation. He clashed repeatedly with William Saurin, the Attorney General for Ireland and most influential figure in the Dublin administration, and political differences between the two men were fuelled by a bitter personal antipathy.[11]

In 1815 a serious event in his life occurred. Dublin Corporation was considered a stronghold of the Protestant Ascendancy and O'Connell, in an 1815 speech, referred to it as a "beggarly corporation".[12] Its members and leaders were outraged and because O'Connell would not apologise, one of their number, the noted duellist John D'Esterre, challenged him. The duel had filled Dublin Castle (from where the British Government administered Ireland) with tense excitement at the prospect that O'Connell would be killed. They regarded O'Connell as "worse than a public nuisance," and would have welcomed any prospect of seeing him removed at this time.[13]

O'Connell met D'Esterre and mortally wounded him (he was shot in the hip, the bullet then lodging in his stomach), in a duel at Oughterard, County Kildare. His conscience was bitterly sore by the fact that, not only had he killed a man, but he had left his family almost destitute.[14]

O'Connell offered to "share his income" with D'Esterre's widow, but she declined; however, she consented to accept an allowance for her daughter, which O'Connell regularly paid for more than thirty years until his death. The memory of the duel haunted him for the remainder of his life, and he refused ever to fight another, being prepared to risk accusations of cowardice rather than kill again.[13]

As part of his campaign for Catholic emancipation, O'Connell created the Catholic Association in 1823; this organisation acted as a pressure group against the British government so as to achieve emancipation. The Catholic Rent, which was established in 1824 by O'Connell and the Catholic Church raised funds from which O'Connell was able to help finance the Catholic Association in its push for emancipation. Official opinion was gradually swinging towards emancipation, as shown by the summary dismissal of William Saurin, the Attorney General and a bigoted opponent of religious toleration, whom O'Connell called "our mortal foe".

O'Connell stood in a by-election to the British House of Commons in 1828 for County Clare for a seat vacated by William Vesey Fitzgerald, another supporter of the Catholic Association.

After O'Connell won election, he was unable to take his seat as members of parliament had to take the Oath of Supremacy, which was incompatible with Catholicism. The Prime Minister, the Duke of Wellington, and the Home Secretary, Sir Robert Peel, even though they opposed Catholic participation in Parliament, saw that denying O'Connell his seat would cause outrage and could lead to another rebellion or uprising in Ireland, which was about 85% Catholic.[15]

Peel and Wellington managed to convince George IV that Catholic emancipation and the right of Catholics and Presbyterians and members of all Christian faiths other than the established Church of Ireland to sit in Parliament needed to be established; with the help of the Whigs, it became law in 1829.

However, the Emancipation Act was not made retrospective, meaning that O'Connell had either to seek re-election or to attempt to take the oath of supremacy. When O'Connell attempted on 15 May to take his seat without taking the oath of supremacy,[16] Solicitor-General Nicholas Conyngham Tindal moved that his seat be declared vacant and another election ordered; O'Connell was elected unopposed on 30 July 1829.[17]

He took his seat when Parliament resumed in February 1830, by which time Henry Charles Howard, 13th Duke of Norfolk and Earl of Surrey, had already become the first Roman Catholic to have taken advantage of the Emancipation Act and sit in Parliament.[18][19]

"Wellington is the King of England", King George IV once complained, "O'Connell is King of Ireland, and I am only the dean of Windsor." The regal jest expressed the general admiration for O'Connell at the height of his career.

The Catholic emancipation campaign led by O'Connell served as the precedent and model for the emancipation of British Jews, the subsequent Jews Relief Act 1858 allowing Jewish MPs to omit the words in the Oath of Allegiance "and I make this Declaration upon the true Faith of a Christian".[20]

The Tithe War

Ironically, considering O'Connell's dedication to peaceful methods of political agitation,[21] his greatest political achievement ushered in a period of violence in Ireland. There was an obligation for those working the land to support the established Church (i.e., the United Church of England and Ireland) by payments known as tithes. The fact that the vast majority of those working the land in Ireland were Catholic or Presbyterian tenant farmers, supporting what was a minority religion within that island (but not the United Kingdom as a whole), had been causing tension for some time.[22]

In December 1830, he and several others were tried for holding a meeting as an association or assemblage in violation of the orders of the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, but the statute expired in course of judgment and the prosecution was terminated by the judiciary.[23]

An initially peaceful campaign of non-payment turned violent in 1831 when the newly founded Irish Constabulary were used to seize property in lieu of payment resulting in the Tithe War of 1831–36.

Although opposed to the use of force, O'Connell successfully defended participants in the Battle of Carrickshock and all the defendants were acquitted. Nonetheless O'Connell rejected William Sharman Crawford's call for the complete abolition of tithes in 1838, as he felt he could not embarrass the Whigs (the Lichfield House Compact secured an alliance between Whigs, radicals and Irish MPs in 1835).[22]

In 1841, Daniel O'Connell became the first Roman Catholic Lord Mayor of Dublin since the reign of James II, who had been the last Roman Catholic monarch of England, Ireland and Scotland.[3]

Campaign for repeal of the Union

Once Catholic emancipation was achieved, O'Connell campaigned for repeal of the Act of Union, which in 1801 had merged the Parliaments of the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. To campaign for repeal, O'Connell set up the Repeal Association. He argued for the re-creation of an independent Kingdom of Ireland to govern itself, with Queen Victoria as the Queen of Ireland.

To push for this, he held a series of "Monster Meetings" throughout much of Ireland outside the Protestant and Unionist-dominated province of Ulster. They were so called because each was attended by around 100,000 people. These rallies concerned the British Government and the Prime Minister, Sir Robert Peel, banned one such proposed monster meeting at Clontarf, County Dublin, just outside Dublin city in 1843. This move was made after the biggest monster meeting was held at Tara.

Tara held great significance to the Irish population as it was the historic seat of the High Kings of Ireland. Clontarf was symbolic because of its association with the Battle of Clontarf in 1014, when the Irish King Brian Boru defeated his rival Maelmordha, although Brian himself died during the battle. Despite appeals from his supporters, O'Connell refused to defy the authorities and he called off the meeting, as he was unwilling to risk bloodshed and had no others.[3] He was arrested, charged with conspiracy and sentenced to a year's imprisonment and a fine of £2,000, although he was released after three months by the House of Lords, which quashed the conviction and severely criticised the unfairness of the trial. Having deprived himself of his most potent weapon, the monster meeting, O'Connell with his health failing had no plan and dissension broke out in the Repeal Association.[3]

Legacy

issued in 1929.

O'Connell died of softening of the brain (cerebral softening) in 1847 in Genoa, Italy, while on a pilgrimage to Rome at the age of 71; his term in prison had seriously weakened him, and the appallingly cold weather he had to endure on his journey was probably the final blow. According to his dying wish, his heart was buried in Rome (at Sant'Agata dei Goti, then the chapel of the Irish College), and the remainder of his body in Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin, beneath a round tower. His sons are buried in his crypt.

On 6 August 1875, Charles Herbert Mackintosh won the gold and silver medals offered by the St. Patrick's Society during the O'Connell centenary at Major's Hill Park in Ottawa, Ontario for a prize poem entitled, The Irish Liberator.[24]

O'Connell's philosophy and career have inspired leaders all over the world, including Mahatma Gandhi (1869–1948) and Martin Luther King (1929–1968). He was told by William Makepeace Thackeray (1811–1863) "you have done more for your nation than any man since Washington ever did." William Gladstone (1809–1898) described him as "the greatest popular leader the world has ever seen." Honoré de Balzac (1799–1850) wrote that "Napoleon and O'Connell were the only great men the 19th century had ever seen." Jean-Henri Merle d'Aubigné (1794–1872) wrote that "the only man like Luther, in the power he wielded was O'Connell." William Grenville (1759–1834) wrote that "history will speak of him as one of the most remarkable men that ever lived." O'Connell met, befriended, and became a great inspiration to Frederick Douglass (1818–1895) a former American slave who became a highly influential leader of the abolitionist movement, social reformer, orator, writer and statesman.[25][26] O'Connell's attacks on slavery were made with his usual vigour, and often gave great offence, especially in the United States: he called George Washington a hypocrite, and was challenged to a duel by Andrew Stevenson, the American Minister, whom he was reported to have called a slave breeder.

However, the founder of the Irish Labour Party and executed Easter Rising leader James Connolly, devoted a chapter in his 1910 book "Labour in Irish History" entitled "A chapter of horrors: Daniel O’Connell and the working class." in which he criticised O'Connell's parliamentary record, accusing him of siding consistently with the interests of the propertied classes of the United Kingdom.[27] And Patrick Pearse, Connolly's fellow leader of the Easter Rising, wrote: "The leaders in Ireland have nearly always left the people at the critical moment.(...) O’Connell recoiled before the cannon at Clontarf" though adding "I do not blame these men; you or I might have done the same. It is a terrible responsibility to be cast on a man, that of bidding the cannon speak and the grapeshot pour".[28]

In O'Connell's lifetime, the aims of his Repeal Association—an independent Kingdom of Ireland governing itself but keeping the British monarch as its Head of State—proved too radical for the British government of the time to accept, and brought upon O'Connell persecution and suppression.

O'Connell is known in Ireland as "The Liberator" or "The Great Emancipator" for his success in achieving Catholic Emancipation. O'Connell admired Latin American liberator Simón Bolívar, and one of his sons, Morgan O'Connell, was a volunteer officer in Bolívar's army in 1820, aged 15.[29] The principal street in the centre of Dublin, previously called Sackville Street, was renamed O'Connell Street in his honour in the early 20th century after the Irish Free State came into being.[30] His statue (made by the sculptor John Henry Foley, who also designed the sculptures of the Albert Memorial in London) stands at one end of the street, with a statue of Charles Stewart Parnell at the other end.[31]

The main street of Limerick is also named after O'Connell, also with a statue at the end (in the centre of the Crescent). O'Connell Streets also exist in Ennis, Sligo, Athlone, Kilkee, Clonmel and Waterford.

There is a statue honouring O'Connell outside St Patrick's Cathedral in Melbourne, Australia, as until the 1950s, the Archdiocese of Melbourne was almost entirely made up of Irish immigrants or Australians of Irish descent.[32] There is a museum commemorating him in Derrynane House, near the village of Derrynane, County Kerry, which was once owned by his family.[33] He was a member of the Literary Association of the Friends of Poland as well.[34]

Family

In 1802 O'Connell married his third cousin, Mary O'Connell. It was a love marriage, and to persist in it was an act of considerable courage, since Daniel's uncle Maurice was outraged (as Mary had no fortune) and for a time threatened to disinherit them.[35] They had four daughters (three surviving), Ellen (1805–1883), Catherine (1808), Elizabeth (1810), and Rickard (1815) and four sons. The sons—Maurice (1803), Morgan (1804), John (1810), and Daniel (1816)—all sat in Parliament. The marriage was happy and Mary's death in 1837 was a blow from which her husband never fully recovered. He was a devoted father; O'Faoláin suggests that despite his wide acquaintance he had few close friends and therefore the family circle meant a great deal to him.[36]

Connection with the licensed trade

O'Connell assisted his younger son, Daniel junior, to acquire the Phoenix Brewery in James's Street, Dublin in 1831.[37] The brewery produced a brand known as "O'Connell's Ale" and enjoyed some popularity. By 1832, O'Connell was forced to state that he would not be a political patron of the brewing trade or his son's company, until he was no longer a member of parliament, particularly because O'Connell and Arthur Guinness were political enemies. Guinness was the "moderate" liberal candidate, O'Connell was the "radical" liberal candidate. The rivalry caused dozens of Irish firms to boycott Guinness during the 1841 Repeal election. It was at this time that Guinness was accused of supporting the "Orange system", and its beer was known as "Protestant porter". When the O'Connell family left brewing, the rights to "O'Connell Dublin Ale" was sold to John D'Arcy. The brewing business proved to be unsuccessful though, and after a few years was taken over by the manager, John Brennan, while Daniel junior embraced a political career. Brennan changed the name back to the Phoenix Brewery but continued to brew and sell O'Connell's Ale. When the Phoenix Brewery was effectively closed after being absorbed into the Guinness complex in 1909, the brewing of O'Connell's Ale was carried out by John D'Arcy and Son Ltd at the Anchor Brewery in Usher Street. In 1926, D'Arcy's ceased trading and the firm of Watkins, Jameson and Pim carried on the brewing until they too succumbed to the pressures of trying to compete with Guinness.[38][39]

Daniel junior was the committee chairman of the licensed trade association of the period and gave considerable and valuable support to Daniel O'Connell in his public life. Some time later a quarrel arose and O'Connell turned his back on the association and became a strong advocate of temperance. During the period of Fr. Mathew's total abstinence crusades many temperance rallies were held, the most notable being a huge rally held on St. Patrick's Day in 1841. Daniel O'Connell was a guest of honour at another such rally held at the Rotunda Hospital.[39][40]

Comments on emancipation

- ^ The Anti-Slavery Society Convention, 1840, Benjamin Robert Haydon, 1841, National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG599, Given by British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society in 1880

Michael Doheny, in his The Felon's Track, says that the very character of emancipation has assumed an "exaggerated and false guise" and that it is an error to call it emancipation. He went on, that it was neither the first nor the last nor even the most important in the concessions, which are entitled to the name of emancipation, and that no one remembered the men whose exertions "wrung from the reluctant spirit of a far darker time the right of living, of worship, of enjoying property, and exercising the franchise."[41] Doheny's opinion was, that the penalties of the "Penal Laws" had been long abolished, and that barbarous code had been compressed into cold and stolid exclusiveness and yet Mr. O'Connell monopolised its entire renown.[41] The view put forward by John Mitchel, also one of the leading members of the Young Ireland movement, in his "Jail Journal"[42] was that there were two distinct movements in Ireland during this period, which were rousing the people, one was the Catholic Relief Agitation (led by O'Connell), which was both open and legal, the other was the secret societies known as the Ribbon and White—boy movements.[43] The first proposed the admission of professional and genteel Catholics to Parliament and to the honours of the professions, all under British law—the other, originating in an utter horror and defiance of British law, contemplated nothing less than a social, and ultimately, a political revolution.[43] According to Mitchel, for fear of the latter, Great Britain with a "very ill grace yielded to the first". Mitchel agrees that Sir Robert Peel and the Duke of Wellington said they brought in this measure, to avert civil war; but says that "no British statesman ever officially tells the truth, or assigns to any act its real motive."[43] Their real motive was, according to Mitchel, to buy into the British interests, the landed and educated Catholics, these "Respectable Catholics" would then be contented, and "become West Britons" from that day.[43]

Political beliefs and programme

A critic of violent insurrection in Ireland, O'Connell once said that "the altar of liberty totters when it is cemented only with blood," and yet as late as 1841, O'Connell had whipped his MPs into line to keep the "Opium War" going in China. The Tories at the time had proposed a motion of censure over the war, and O'Connell had to call upon his MPs to support the Whig Government. As a result of this intervention, the Government was saved.[44]

Politically, he focused on parliamentary and populist methods to force change and made regular declarations of his loyalty to the British Crown. He often warned the British establishment that if they did not reform the governance of Ireland, Irishmen would start to listen to the "counsels of violent men". Successive British governments continued to ignore this advice, long after his death, although he succeeded in extracting by the sheer force of will and the power of the Catholic peasants and clergy much of what he wanted, i.e., eliminating disabilities on Roman Catholics; ensuring that lawfully elected Roman Catholics could serve their constituencies in the British Parliament (until the Irish Parliament was restored); and amending the Oath of Allegiance so as to remove clauses offensive to Roman Catholics who could then take the Oath in good conscience.[3]

Although a native speaker of the Irish language, O'Connell encouraged Irish people to learn English to better themselves.[3] Although he is best known for the campaign for Catholic emancipation; he also supported similar efforts for Irish Jews. At his insistence, in 1846, the British law "De Judaismo", which prescribed a special dress for Jews, was repealed. O'Connell said: "Ireland has claims on your ancient race, it is the only country that I know of unsullied by any one act of persecution of the Jews".[45] But in a heated debate in parliament, over press reports that O'Connell had been called a 'traitor and incendiary' by Disraeli, O'Connell referred to Disraeli's Jewish ancestry in disparaging terms to which Disraeli responded: "Yes, I am a Jew and when the ancestors of the right honourable gentleman were brutal savages in an unknown island, mine were priests in the temple of Solomon."[46]

O'Connell quotations

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Daniel O'Connell |

- 'The altar of liberty totters when it is cemented only with blood' [Written in his Journal, Dec 1796, and one of O'Connell's most well-known quotes. Quoted by O'Ferrall, F., Daniel O'Connell, Dublin, 1981, p. 12]

- "Gentlemen, you may soon have the alternative to live as slaves or die as free men" (speaking in Mallow, County Cork)

- 'Good God, what a brute man becomes when ignorant and oppressed. Oh Liberty! What horrors are committed in thy name! May every virtuous revolutionist remember the horrors of Wexford'! [Written in his Journal, 2 Jan 1799, referring to the recent 1798 Rebellion. Quoted from Vol I, p. 205, of O'Neill Daunt, W. J., Personal Recollections of the Late Daniel O'Connell, M.P., 2 Vols, London, 1848.]

- 'My days—the blossom of my youth and the flower of my manhood—have been darkened by the dreariness of servitude. In this my native land—in the land of my sires—I am degraded without fault as an alien and an outcast.' [July 1812, aged 37, reflecting on the failure to secure equal rights or Catholic Emancipation for Catholics in Ireland. Quoted from Vol I, p. 185, of O'Connell, J. (ed.) The Life and Speeches of Daniel O'Connell, 2 Vols, Dublin, 1846)]

- 'How cruel the Penal Laws are which exclude me from a fair trial with men whom I look upon as so much my inferiors ...'. [O'Connell's Correspondence, Letter No 700, Vol II]

- '... I want to make all Europe and America know it—I want to make England feel her weakness if she refuses to give the justice we [the Irish] require—the restoration of our domestic parliament ...'. [Speech given at a 'monster' meeting held at Drogheda, June 1843]

- 'There is an utter ignorance of, and indifference to, our sufferings and privations ... What care they for us, provided we be submissive, pay the taxes, furnish recruits for the Army and Navy and bless the masters who either despise or oppress or combine both? The apathy that exists respecting Ireland is worse than the national antipathy they bear us'. [Letter to T.M. Ray, 1839, on English attitudes to Ireland (O'Connell Correspondence, Vol VI, Letter No. 2588)]

- 'No person knows better than you do that the domination of England is the sole and blighting curse of this country. It is the incubus that sits on our energies, stops the pulsation of the nation's heart and leaves to Ireland not gay vitality but horrid the convulsions of a troubled dream'. [Letter to Bishop Doyle, 1831 (O'Connell Correspondence, Vol IV, Letter No. 1860)]

- 'The principle of my political life ... is, that all ameliorations and improvements in political institutions can be obtained by persevering in a perfectly peaceable and legal course, and cannot be obtained by forcible means, or if they could be got by forcible means, such means create more evils than they cure, and leave the country worse than they found it.' [Writing in The Nation newspaper, 18 November 1843]

- "No man was ever a good soldier but the man who goes into the battle determined to conquer, or not to come back from the battle field (cheers). No other principle makes a good soldier." O'Connell recalling the spirited conduct of the Irish soldiers in Wellington's army, at the Monster meeting held at Mullaghmast.[47][48]

- "The poor old Duke [of Wellington]! What shall I say of him? To be sure he was born in Ireland, but being born in a stable does not make a man a horse." Shaw's Authenticated Report of the Irish State Trials (1844), p. 93

- "Every religion is good—every religion is true to him who in his good caution and conscience believes it". (As defence counsel in R. v Magee (1813), pleading for religious tolerance.)[49]

- "Ireland is too poor for a poor law". (In response to the Poor Relief Act of 1839 that set up the workhouses.)[50]

See also

- History of Ireland (1801-1922)

- Irish nobility

- List of people on stamps of Ireland

- Daniel O'Connell Heritage Summer School

Footnotes

- ↑ "O'Connell, Daniel - Irish Cultural Society of the Garden City Area". irish-society.org.

- ↑ A Short History of Ireland

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Boylan, Henry (1998). A Dictionary of Irish Biography (3rd ed.). Dublin: Gill and MacMillan. p. 306. ISBN 0-7171-2945-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dennis Gywnn, Daniel O'Connell The Irish Liberator, Hutchinson & Co. Ltd pg 71

- ↑ O'Connell Correspondence, Vol I, Letter No. 24a

- ↑ O'Ferrall, F., Daniel O'Connell, Dublin, 1981, p. 12

- ↑ O'Connell Correspondence, Vol I, Letter No. 97

- ↑ O'Faoláin, Sean King of the Beggars- a life of Daniel O'Connell 1936 Alan Figgis reissue p.97

- ↑ Great Britain and the Irish Question 1798–1922, Paul Adelmann and Robert Pearce, Hodder Murray, London, ISBN 0-340-88901-2.pg 33

- ↑ Geoghegan, Patrick M. King Dan Gill and Macmillan 2008 Dublin p.168

- ↑ O'Faoláin pp.151–179

- ↑ Millingen, John Gideon (1841). The history of duelling: including, narratives of the most remarkable personal encounters that have taken place from the earliest period to the present time, Volume 2. R. Bentley. p. 215.

- 1 2 Dennis Gywnn, Daniel O'Connell The Irish Liberator, Hutchinson & Co. Ltd pp 138–145

- ↑ Geoghegan King Dan p155

- ↑ Oliver MacDonagh, The Life of Daniel O'Connell 1991

- ↑ "This day, May 15, in Jewish history". Cleveland Jewish News.

- ↑ History of Parliament 1820–1832 vol VI pp. 535–6.

- ↑ History of Parliament 1820–1832 vol I p. 253.

- ↑ "The Grail Chapter Eight". deskeenan.com.

- ↑ "Jews Relief Act 1858". legislation.gov.uk.

- ↑ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Daniel O'Connell". newadvent.org.

- 1 2 Stewart, Jay Brown (2001). The National Churches of England, Ireland and Scotland, 1801–46. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 20–45. ISBN 0-19-924235-6.

- ↑ State Trials (New Series) II, 629

- ↑ Canadian Illustrated News 28 08 1875 vol.XII, no. 9, 136 Library & Archives Canada 3682 Canadian Illustrated News

- ↑ Douglass, Frederick (1882). The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass: From 1817-1882. p. 205. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- ↑ Chaffin, Tom (25 February 2011). "Frederick Douglass's Irish Liberty". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- ↑ James Connolly. "James Connolly: Labour in Irish History - Chapter 12". marxists.org.

- ↑ Seán Cronin, Our Own Red Blood, Irish Freedom Press, New York, 1966, pg.15

- ↑ Brian McGinn (November 1991). "Venezuela's Irish Legacy". Irish America Magazine (New York) Vol. VII, No. XI. Retrieved 18 April 2007.

- ↑ Sheehan, Sean and Levy, Patricia (2001). Dublin Handbook: The Travel Guide. Footprint Handbooks. p. 99. ISBN 978-1-900949-98-9.

- ↑ Bennett, Douglas (2005). Encyclopedia of Dublin. Dublin: Gill and MacMillan. ISBN 978-0-7171-3684-1.

- ↑ O'Farrell, Patrick (1977). The Catholic Church and Community in Australia. Thomas Nelson (Australia), west Melbourne.

- ↑ "Derrynane House". Derrynane House. Retrieved 23 January 2009.

- ↑ Marchlewicz K: The Pro-Polish Loby in the House of Commons and the House of Lords During the 1830s and 1840s. Przeglad Historyczny (Historical Review) year: 2005, vol: 96, number: 1, pages: 61–76

- ↑ Geoghegan King Dan pp.94–7

- ↑ O'Faoláin p.87

- ↑ Irish Whiskey: A 1000 Year Tradition, Malachy Magee, O'Brien Press, Dublin, ISBN 0-86278-228-7. pg 68–74.

- ↑ T. Halpin: History of the Irish Brewing Industry, 1988

- 1 2 History of Brewing in Dublin

- ↑ St Martin Magazine (ISSN 1393-1008), June 2003 St Martin Apostolate, Dublin

- 1 2 Michael Doheny's The Felon's Track, M. H. Gill & Son, Ltd., 1951, pp 2–4

- ↑ John Mitchel's Jail Journal which was first serialised in his first New York City newspaper, The Citizen, from 14 January 1854 to 19 August 1854. The book referenced is an exact reproduction of the Jail Journal, as it first appeared.

- 1 2 3 4 John Mitchel, Jail Journal, or five years in British Prisons, M. H. Gill & Son, Ltd., 1914, pp. xxxiv–xxxvi

- ↑ Charles Gavan Duffy: Conversations With Carlyle (1892), with Introduction, Stray Thoughts on Young Ireland, Brendan Clifford, Athol Books, Belfast, ISBN 0-85034-114-0.pg 17 &21

- ↑ Jewish Ireland

- ↑ http://www.victorianweb.org/history/pms/dizzy.html

- ↑ Envoi, Taking Leave of Roy Foster, by Brendan Clifford and Julianne Herlihy, Aubane Historical Society, Cork.pg 16

- ↑ Allen, Edward Archibald; William Schuyler (1901). David Josiah Brewer, ed. The world's best orations: from the earliest period to the present time 8. F. P. Kaiser. p. 3101. Retrieved 23 March 2010.

- ↑ O'Faoláin p.163

- ↑ Angus McIntyre, 'The Liberator: Daniel O'Connell and the Irish Party 1830–47'. Published, London, 1965, pp. 211–18.

References

- Fergus O'Ferrall, Daniel O'Connell (Gill's Irish Lives Series), Gill & MacMillan, Dublin, 1981.

- Seán Ó Faoláin, King of the Beggars: A Life of Daniel O'Connell, 1938.

- Maurice R. O'Connell, The Correspondence of Daniel O'Connell (8 Vols), Dublin, 1972–1980.

- Oliver MacDonagh, O'Connell: The Life of Daniel O'Connell 1775–1847 1991.

- J. O'Connell, ed., The Life and Speeches of Daniel O'Connell (2 Vols), Dublin, 1846.

- Sister Mary Francis Cusask, Life of Daniel O'Connell, the Liberator: His Times – Political, Social, and Religious. New York: D. & J. Sadlier & Co. 1872.

- h-net.org

Further reading

- Anonymous (1911). "Daniel O'Connell". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.).

-

d'Alton, E. A. (1913). "Daniel O'Connell". In Herbermann, Charles. Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton.

d'Alton, E. A. (1913). "Daniel O'Connell". In Herbermann, Charles. Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton. - Lee, Sidney, ed. (1895). "O'Connell, Daniel (1775–1847)". Dictionary of National Biography 41. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 371–389.

- Philp, Robert Kemp (1861). "O'Connell, Morgan". The dictionary of useful knowledge. Oxford University.

- The Great Dan, Charles Chenevix Trench, Jonathan Cape Ltd., 1984.

- King Dan the Rise of Daniel O'Connell 1775–1829, Patrick Geoghegan, Gill and Macmillan, 2008.

- John Mitchel, A Cause Too Many, Aidan Hegarty, Camlane Press.

- Thomas Davis, The Thinker and Teacher, Arthur Griffith, M.H. Gill & Son, 1922.

- Daniel O'Connell: The Irish Liberator, Dennis Gwynn, Hutchinson & Co, Ltd.

- O'Connell, Davis and the Collages Bill, Dennis Gwynn, Cork University Press 1948.

- Labour in Ireland, James Connolly, Fleet Street 1910.

- The Re-Conquest of Ireland, James Connolly, Fleet Street 1915.

- John Mitchel: Noted Irish Lives, Louis J. Walsh, The Talbot Press Ltd., 1934.

- Life of John Martin, P. A. Sillard, James Duffy & Co., Ltd 1901.

- Ireland Her Own, T. A. Jackson, Lawrence & Wishart Ltd 1976.

- Life and Times of Daniel O'Connell, T. C. Luby, Cameron & Ferguson.

- Paddy's Lament: Ireland 1846–1847, Prelude to Hatred, Thomas Gallagher, Poolbeg 1994.

- The Great Shame, Thomas Keneally, Anchor Books 1999.

- Envoi, Taking Leave of Roy Foster, by Brendan Clifford and Julianne Herlihy, Aubane Historical Society, Cork.

- In Search of Ireland's Heroes, Carmel McCaffrey. Ivan R Dee Publisher

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Daniel O'Connell. |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Daniel O'Connell |

- Daniel O'Connell and Newfoundland

- Modern History Sourcebook: Daniel O'Connell: Justice for Ireland, Feb 4, 1836—O'Connell's speech in the House of Commons

- Daniel O’Connell—Multitext Project in Irish History (with extensive image gallery)

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by Daniel O'Connell

- Daniel O'Connell Collection – at Boston College John J. Burns Library

| Parliament of the United Kingdom | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by William Vesey-FitzGerald Lucius O'Brien |

Member of Parliament for Clare 1828–1830 With: Lucius O'Brien |

Succeeded by William Nugent Macnamara Charles Mahon |

| Preceded by Richard Power Lord George Beresford |

Member of Parliament for County Waterford 1830–1831 With: Lord George Beresford |

Succeeded by Sir Richard Musgrave, Bt Robert Power |

| Preceded by Maurice Fitzgerald William Browne |

Member of Parliament for Kerry 1831–1832 With: Frederick William Mullins |

Succeeded by Frederick William Mullins Charles O'Connell |

| Preceded by Sir Frederick Shaw, 3rd Baronet Viscount Ingestre |

Member of Parliament for Dublin City 1832–1835 With: Edward Southwell Ruthven |

Succeeded by George Alexander Hamilton John Beattie West |

| Preceded by Richard Sullivan |

Member of Parliament for Kilkenny City 1836–1837 |

Succeeded by Joseph Hume |

| Preceded by George Alexander Hamilton John Beattie West |

Member of Parliament for Dublin City 1837–1841 With: Robert Hutton |

Succeeded by John Beattie West Edward Grogan |

| Preceded by Matthew Elias Corbally |

Member of Parliament for Meath 1841–1842 With: Henry Grattan |

Succeeded by Matthew Elias Corbally |

| Preceded by Garrett Standish Barry Edmund Burke Roche |

Member of Parliament for Cork County 1841–1847 With: Edmund Burke Roche |

Succeeded by Edmund Burke Roche Maurice Power |

| Civic offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Sir John Kingston James |

Lord Mayor of Dublin 1841–1842 |

Succeeded by George Roe |

|