Tecopa pupfish

| Tecopa pupfish | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Cyprinodontiformes |

| Family: | Cyprinodontidae |

| Genus: | Cyprinodon |

| Species: | C. nevadensis |

| Subspecies: | C. n. calidae |

| Trinomial name | |

| Cyprinodon nevadensis calidae R. R. Miller, 1948 | |

The Tecopa pupfish (Cyprinodon nevadensis calidae) is an extinct subspecies of the Amargosa pupfish (Cyprinodon nevadensis). The small, heat-tolerant pupfish was endemic to the outflows of a pair of hot springs in the Mojave Desert of California. Habitat modifications and the introduction of non-native species led to its extinction in about 1970.

Taxonomy

The Tecopa pupfish is member of the genus Cyprinodon of the pupfish family Cyprinodontidae, a taxon of killifish most diverse in North America. Most divergence of local Cyprinodon species likely took place during the early-to-mid Pleistocene, a time when pluvial lakes intermittently filled the now-desert region, though some may have occurred during the last 10,000 years. The evaporation of the lakes resulted in the geographic isolation of small Cyprinodon populations in remnant wetlands and the speciation of C. nevadensis.[1]

C. n. calidae was first described as a subspecies in 1948 by Robert Rush Miller,[2] after six years of study.[3] Miller also identified five other subspecies: the Amargosa River pupfish (C. n. amargosae), the Ash Meadows pupfish (C. n. mionectes), the Saratoga Springs pupfish (C. n. nevadensis), the Warm Springs pupfish (C. n. pectoralis), and the Shoshone pupfish (C. n. shoshone).[4]

Other local Cyprinodons include the Death Valley pupfish (Cyprinodon salinus), the Devil's Hole pupfish, (Cyprinodon diabolis) the desert pupfish (Cyprinodon macularius) and the Owens pupfish (Cyprinodon radiosus).

Description and behavior

The fish were about 1–1.5 inches (2.5–4 cm) in length. The dorsal fin was positioned closer to the tail than the head. The pelvic fin was small or sometimes absent, and had six lepidotrichia. Similar to some other Cyprinodons, breeding males displayed a bright blue coloration. Females had between six and ten vertical stripes.[5]

C. n. calidae primarily ate cyanobacteria (blue-green algae). Invertebrates such as mosquito larvae provided occasional nutrition.[5] The fish were capable of surviving water temperatures of 110 degrees Fahrenheit (43 °C)[6] or more.[7]

Decline and extinction

Tecopa Hot Springs lies at an elevation of 1,411 feet (430 m), about 2 miles north of the town of Tecopa in Inyo County, California.[8] The outflows of the two hot springs are tributaries of the Amargosa River, and were the only place where C. n. calidae existed.[6]

The popularity of the springs in the 1950s and 1960s led to the extensive alteration of the pupfishes' habitat. During the construction of bathhouses, the hot spring pools were enlarged and the outflows diverted.[7] In 1965, the outflows of the northern and southern hot springs were re-channeled and merged. The resulting swifter currents caused downstream water temperatures to rise above a level to which the pupfish were adapted.[6] Modifications also allowed the related Amargosa River pupfish (C. n. amargosae) to migrate upstream from the Amargosa River and hybridize with the Tecopa pupfish.[7]

In 1966, Miller found that the population at Tecopa Hot Springs was nearly extinct. A population was found at a reservoir at a nearby motel two years later, but its smaller scales suggested that it may have already hybridized with the Amargosa River pupfish.[9] In 1970, concerns over this habitat alteration and the presence of non-native species such as the bluegill and the western mosquitofish led to its inclusion in both Federal and California lists of endangered species.[2]

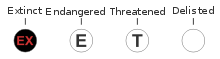

The last confirmed specimens of C. n. calidae were collected on February 2, 1970, and the subspecies was probably extinct by the next year.[7] Further surveys in 1972 and 1977 returned no examples of the fish.[7] In 1978, United States Fish and Wildlife Service announced that it was considering delisting the fish, with Assistant Secretary of the Interior Robert L. Herbst calling the loss "totally avoidable" and saying, "The human projects which so disrupted its habitat, if carefully planned, could have ensured its survival."[10] In 1981, after an exhaustive search of over 40 locations, the Fish and Wildlife Service officially declared the fish extinct. It was the first animal removed from the provisions of the 1973 Endangered Species Act as a result of its extinction.[6]

References

- ↑ Moyle, Peter B.; Yoshiyame, Ronald M.; Williams, Jack E.; Wirkamanayake, Eric D. (June 1995). "Fish Species of Special Concern in California" (PDF). California Department of Fish and Game. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- 1 2 Noecker, Robert J. (5 January 1998). "98-32: Endangered Species List Revisions: A Summary of Delisting and Downlisting" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ↑ Saar, John; Adelson, Suzanne (21 December 1981). "The Tecopa Pupfish Is An Endangered Species No More—Now It's Extinct". People. Retrieved 4 May 2011.

- ↑ "Cyprinodon nevadensis". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 4 May 2011.

- 1 2 Endangered wildlife of California. California Department of FIsh and Game. pp. 42–43.

- 1 2 3 4 Levitt, Alan (18 November 1981). "TECOPA PUPFISH DECLARED EXTINCT--REMOVED FROM ENDANGERED LIST" (PDF). United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Miller, Robert R.; Williams, James D.; Williams, Jack E. (1989). "Extinctions of North American Fishes During the Past Century" (PDF). Fisheries 14 (6): 30. doi:10.1577/1548-8446(1989)014<0022:eonafd>2.0.co;2. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ↑ "Tecopa Hot Springs". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- ↑ Miller, Robert R. (1969). "Conservation of Fishes of the Death Valley System in California and Nevada" (PDF). The Western Section of The Wildlife Society. Retrieved 4 May 2011.

- ↑ Levitt, Alan (3 July 1978). "EXTINCTION TO REMOVE FISH FROM ENDANGERED SPECIES LIST" (PDF). United States Fish and WIldlife Service. Retrieved 4 May 2011.