Data integration

Data integration involves combining data residing in different sources and providing users with a unified view of these data.[1] This process becomes significant in a variety of situations, which include both commercial (when two similar companies need to merge their databases) and scientific (combining research results from different bioinformatics repositories, for example) domains. Data integration appears with increasing frequency as the volume and the need to share existing data explodes.[2] It has become the focus of extensive theoretical work, and numerous open problems remain unsolved.

History

Issues with combining heterogeneous data sources, often referred to as information silos, under a single query interface have existed for some time. In the early 1980s, computer scientists began designing systems for interoperability of heterogeneous databases.[3] The first data integration system driven by structured metadata was designed at the University of Minnesota in 1991, for the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS). IPUMS used a data warehousing approach, which extracts, transforms, and loads data from heterogeneous sources into a single view schema so data from different sources become compatible.[4] By making thousands of population databases interoperable, IPUMS demonstrated the feasibility of large-scale data integration. The data warehouse approach offers a tightly coupled architecture because the data are already physically reconciled in a single queryable repository, so it usually takes little time to resolve queries.[5]

The data warehouse approach is less feasible for datasets that are frequently updated, requiring the ETL process to be continuously re-executed for synchronization. Difficulties also arise in constructing data warehouses when one has only a query interface to summary data sources and no access to the full data. This problem frequently emerges when integrating several commercial query services like travel or classified advertisement web applications.

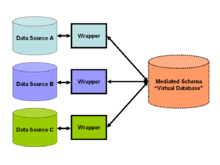

As of 2009 the trend in data integration favored loosening the coupling between data and providing a unified query-interface to access real time data over a mediated schema (see figure 2), which allows information to be retrieved directly from original databases. This is consistent with the SOA approach popular in that era. This approach relies on mappings between the mediated schema and the schema of original sources, and transform a query into specialized queries to match the schema of the original databases. Such mappings can be specified in 2 ways : as a mapping from entities in the mediated schema to entities in the original sources (the "Global As View" (GAV) approach), or as a mapping from entities in the original sources to the mediated schema (the "Local As View" (LAV) approach). The latter approach requires more sophisticated inferences to resolve a query on the mediated schema, but makes it easier to add new data sources to a (stable) mediated schema.

As of 2010 some of the work in data integration research concerns the semantic integration problem. This problem addresses not the structuring of the architecture of the integration, but how to resolve semantic conflicts between heterogeneous data sources. For example, if two companies merge their databases, certain concepts and definitions in their respective schemas like "earnings" inevitably have different meanings. In one database it may mean profits in dollars (a floating-point number), while in the other it might represent the number of sales (an integer). A common strategy for the resolution of such problems involves the use of ontologies which explicitly define schema terms and thus help to resolve semantic conflicts. This approach represents ontology-based data integration. On the other hand, the problem of combining research results from different bioinformatics repositories requires bench-marking of the similarities, computed from different data sources, on a single criterion such as positive predictive value. This enables the data sources to be directly comparable and can be integrated even when the natures of experiments are distinct.[6]

As of 2011 it was determined that current data modeling methods were imparting data isolation into every data architecture in the form of islands of disparate data and information silos. This data isolation is an unintended artifact of the data modeling methodology that results in the development of disparate data models. Disparate data models, when instantiated as databases, form disparate databases. Enhanced data model methodologies have been developed to eliminate the data isolation artifact and to promote the development of integrated data models.[7][8] One enhanced data modeling method recasts data models by augmenting them with structural metadata in the form of standardized data entities. As a result of recasting multiple data models, the set of recast data models will now share one or more commonality relationships that relate the structural metadata now common to these data models. Commonality relationships are a peer-to-peer type of entity relationships that relate the standardized data entities of multiple data models. Multiple data models that contain the same standard data entity may participate in the same commonality relationship. When integrated data models are instantiated as databases and are properly populated from a common set of master data, then these databases are integrated.

Since 2011, Data hub approaches have been of greater interest than fully structured (typically relational) Enterprise Data Warehouses. Since 2013, Data lake approaches have risen to the level of Data Hubs. (See all three search terms popularity on Google Trends.[9] These approaches combine unstructured or varied data into one location, but do not necessarily require an (often complex) master relational schema to structure and define all data in the Hub.

Example

Consider a web application where a user can query a variety of information about cities (such as crime statistics, weather, hotels, demographics, etc.). Traditionally, the information must be stored in a single database with a single schema. But any single enterprise would find information of this breadth somewhat difficult and expensive to collect. Even if the resources exist to gather the data, it would likely duplicate data in existing crime databases, weather websites, and census data.

A data-integration solution may address this problem by considering these external resources as materialized views over a virtual mediated schema, resulting in "virtual data integration". This means application-developers construct a virtual schema — the mediated schema — to best model the kinds of answers their users want. Next, they design "wrappers" or adapters for each data source, such as the crime database and weather website. These adapters simply transform the local query results (those returned by the respective websites or databases) into an easily processed form for the data integration solution (see figure 2). When an application-user queries the mediated schema, the data-integration solution transforms this query into appropriate queries over the respective data sources. Finally, the virtual database combines the results of these queries into the answer to the user's query.

This solution offers the convenience of adding new sources by simply constructing an adapter or an application software blade for them. It contrasts with ETL systems or with a single database solution, which require manual integration of entire new dataset into the system. The virtual ETL solutions leverage virtual mediated schema to implement data harmonization; whereby the data are copied from the designated "master" source to the defined targets, field by field. Advanced Data virtualization is also built on the concept of object-oriented modeling in order to construct virtual mediated schema or virtual metadata repository, using hub and spoke architecture.

Each data source is disparate and as such is not designed to support reliable joins between data sources. Therefore, data virtualization as well as data federation depends upon accidental data commonality to support combining data and information from disparate data sets. Because of this lack of data value commonality across data sources, the return set may be inaccurate, incomplete, and impossible to validate.

One solution is to recast disparate databases to integrate these databases without the need for ETL. The recast databases support commonality constraints where referential integrity may be enforced between databases. The recast databases provide designed data access paths with data value commonality across databases.

Theory of data integration

The theory of data integration[1] forms a subset of database theory and formalizes the underlying concepts of the problem in first-order logic. Applying the theories gives indications as to the feasibility and difficulty of data integration. While its definitions may appear abstract, they have sufficient generality to accommodate all manner of integration systems,[10] including those that include nested relational / XML databases [11] and those that treat databases as programs.[12] Connections to particular databases systems such as Oracle or DB2 are provided by implementation-level technologies such as JDBC and are not studied at the theoretical level.

Definitions

Data integration systems are formally defined as a triple  where

where  is the global (or mediated) schema,

is the global (or mediated) schema,  is the heterogeneous set of source schemas, and

is the heterogeneous set of source schemas, and  is the mapping that maps queries between the source and the global schemas. Both

is the mapping that maps queries between the source and the global schemas. Both  and

and  are expressed in languages over alphabets composed of symbols for each of their respective relations. The mapping

are expressed in languages over alphabets composed of symbols for each of their respective relations. The mapping  consists of assertions between queries over

consists of assertions between queries over  and queries over

and queries over  . When users pose queries over the data integration system, they pose queries over

. When users pose queries over the data integration system, they pose queries over  and the mapping then asserts connections between the elements in the global schema and the source schemas.

and the mapping then asserts connections between the elements in the global schema and the source schemas.

A database over a schema is defined as a set of sets, one for each relation (in a relational database). The database corresponding to the source schema  would comprise the set of sets of tuples for each of the heterogeneous data sources and is called the source database. Note that this single source database may actually represent a collection of disconnected databases. The database corresponding to the virtual mediated schema

would comprise the set of sets of tuples for each of the heterogeneous data sources and is called the source database. Note that this single source database may actually represent a collection of disconnected databases. The database corresponding to the virtual mediated schema  is called the global database. The global database must satisfy the mapping

is called the global database. The global database must satisfy the mapping  with respect to the source database. The legality of this mapping depends on the nature of the correspondence between

with respect to the source database. The legality of this mapping depends on the nature of the correspondence between  and

and  . Two popular ways to model this correspondence exist: Global as View or GAV and Local as View or LAV.

. Two popular ways to model this correspondence exist: Global as View or GAV and Local as View or LAV.

GAV systems model the global database as a set of views over  . In this case

. In this case  associates to each element of

associates to each element of  a query over

a query over  . Query processing becomes a straightforward operation due to the well-defined associations between

. Query processing becomes a straightforward operation due to the well-defined associations between  and

and  . The burden of complexity falls on implementing mediator code instructing the data integration system exactly how to retrieve elements from the source databases. If any new sources join the system, considerable effort may be necessary to update the mediator, thus the GAV approach appears preferable when the sources seem unlikely to change.

. The burden of complexity falls on implementing mediator code instructing the data integration system exactly how to retrieve elements from the source databases. If any new sources join the system, considerable effort may be necessary to update the mediator, thus the GAV approach appears preferable when the sources seem unlikely to change.

In a GAV approach to the example data integration system above, the system designer would first develop mediators for each of the city information sources and then design the global schema around these mediators. For example, consider if one of the sources served a weather website. The designer would likely then add a corresponding element for weather to the global schema. Then the bulk of effort concentrates on writing the proper mediator code that will transform predicates on weather into a query over the weather website. This effort can become complex if some other source also relates to weather, because the designer may need to write code to properly combine the results from the two sources.

On the other hand, in LAV, the source database is modeled as a set of views over  . In this case

. In this case  associates to each element of

associates to each element of  a query over

a query over  . Here the exact associations between

. Here the exact associations between  and

and  are no longer well-defined. As is illustrated in the next section, the burden of determining how to retrieve elements from the sources is placed on the query processor. The benefit of an LAV modeling is that new sources can be added with far less work than in a GAV system, thus the LAV approach should be favored in cases where the mediated schema is less stable or likely to change.[1]

are no longer well-defined. As is illustrated in the next section, the burden of determining how to retrieve elements from the sources is placed on the query processor. The benefit of an LAV modeling is that new sources can be added with far less work than in a GAV system, thus the LAV approach should be favored in cases where the mediated schema is less stable or likely to change.[1]

In an LAV approach to the example data integration system above, the system designer designs the global schema first and then simply inputs the schemas of the respective city information sources. Consider again if one of the sources serves a weather website. The designer would add corresponding elements for weather to the global schema only if none existed already. Then programmers write an adapter or wrapper for the website and add a schema description of the website's results to the source schemas. The complexity of adding the new source moves from the designer to the query processor.

Query processing

The theory of query processing in data integration systems is commonly expressed using conjunctive queries and Datalog, a purely declarative logic programming language.[14] One can loosely think of a conjunctive query as a logical function applied to the relations of a database such as " where

where  ". If a tuple or set of tuples is substituted into the rule and satisfies it (makes it true), then we consider that tuple as part of the set of answers in the query. While formal languages like Datalog express these queries concisely and without ambiguity, common SQL queries count as conjunctive queries as well.

". If a tuple or set of tuples is substituted into the rule and satisfies it (makes it true), then we consider that tuple as part of the set of answers in the query. While formal languages like Datalog express these queries concisely and without ambiguity, common SQL queries count as conjunctive queries as well.

In terms of data integration, "query containment" represents an important property of conjunctive queries. A query  contains another query

contains another query  (denoted

(denoted  ) if the results of applying

) if the results of applying  are a subset of the results of applying

are a subset of the results of applying  for any database. The two queries are said to be equivalent if the resulting sets are equal for any database. This is important because in both GAV and LAV systems, a user poses conjunctive queries over a virtual schema represented by a set of views, or "materialized" conjunctive queries. Integration seeks to rewrite the queries represented by the views to make their results equivalent or maximally contained by our user's query. This corresponds to the problem of answering queries using views (AQUV).[15]

for any database. The two queries are said to be equivalent if the resulting sets are equal for any database. This is important because in both GAV and LAV systems, a user poses conjunctive queries over a virtual schema represented by a set of views, or "materialized" conjunctive queries. Integration seeks to rewrite the queries represented by the views to make their results equivalent or maximally contained by our user's query. This corresponds to the problem of answering queries using views (AQUV).[15]

In GAV systems, a system designer writes mediator code to define the query-rewriting. Each element in the user's query corresponds to a substitution rule just as each element in the global schema corresponds to a query over the source. Query processing simply expands the subgoals of the user's query according to the rule specified in the mediator and thus the resulting query is likely to be equivalent. While the designer does the majority of the work beforehand, some GAV systems such as Tsimmis involve simplifying the mediator description process.

In LAV systems, queries undergo a more radical process of rewriting because no mediator exists to align the user's query with a simple expansion strategy. The integration system must execute a search over the space of possible queries in order to find the best rewrite. The resulting rewrite may not be an equivalent query but maximally contained, and the resulting tuples may be incomplete. As of 2009 the MiniCon algorithm[15] is the leading query rewriting algorithm for LAV data integration systems.

In general, the complexity of query rewriting is NP-complete.[15] If the space of rewrites is relatively small this does not pose a problem — even for integration systems with hundreds of sources.

Data Integration tools

- Alteryx

- Analytics Canvas

- DataWatch

- Lavastorm

- Paxata

- RapidMiner Studio

Data integration in the life sciences

Large-scale questions in science, such as global warming, invasive species spread, and resource depletion, are increasingly requiring the collection of disparate data sets for meta-analysis. This type of data integration is especially challenging for ecological and environmental data because metadata standards are not agreed upon and there are many different data types produced in these fields. National Science Foundation initiatives such as Datanet are intended to make data integration easier for scientists by providing cyberinfrastructure and setting standards. The five funded Datanet initiatives are DataONE,[16] led by William Michener at the University of New Mexico; The Data Conservancy,[17] led by Sayeed Choudhury of Johns Hopkins University; SEAD: Sustainable Environment through Actionable Data,[18] led by Margaret Hedstrom of the University of Michigan; the DataNet Federation Consortium,[19] led by Reagan Moore of the University of North Carolina; and Terra Populus,[20] led by Steven Ruggles of the University of Minnesota. The Research Data Alliance,[21] has more recently explored creating global data integration frameworks. The OpenPHACTS project, funded through the European Union Innovative Medicines Initiative, built a drug discovery platform by linking datasets from providers such as European Bioinformatics Institute, Royal Society of Chemistry, UniProt, WikiPathways and DrugBank.

See also

- Business semantics management

- Core data integration

- Customer data integration

- Data curation

- Data fusion

- Data mapping

- Data virtualization

- Data Warehousing

- Data wrangling

- Database model

- Datalog

- Dataspaces

- Edge data integration

- Enterprise application integration

- Enterprise Architecture framework

- Enterprise Information Integration (EII)

- Enterprise integration

- Extract, transform, load

- Geodi: Geoscientific Data Integration

- Information integration

- Information Server

- Information silo

- Integration Competency Center

- Integration Consortium

- JXTA

- Master data management

- Object-relational mapping

- Ontology based data integration

- Open Text

- Schema Matching

- Semantic Integration

- SQL

- Three schema approach

- UDEF

- Web service

References

- 1 2 3 Maurizio Lenzerini (2002). "Data Integration: A Theoretical Perspective" (PDF). PODS 2002. pp. 233–246.

- ↑ Frederick Lane (2006). IDC: World Created 161 Billion Gigs of Data in 2006 "IDC: World Created 161 Billion Gigs of Data in 2006" Check

|url= - ↑ John Miles Smith; et al. (1982). "Multibase: integrating heterogeneous distributed database systems". AFIPS '81 Proceedings of the May 4–7, 1981, national computer conference. pp. 487–499.

- ↑ Steven Ruggles, J. David Hacker, and Matthew Sobek (1995). "Order out of Chaos: The Integrated Public Use Microdata Series". Historical Methods 28. pp. 33–39.

- ↑ Jennifer Widom (1995). "Research problems in data warehousing". CIKM '95 Proceedings of the fourth international conference on information and knowledge management. pp. 25–30.

- ↑ Shubhra S. Ray; et al. (2009). "Combining Multi-Source Information through Functional Annotation based Weighting: Gene Function Prediction in Yeast" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 56 (2): 229–236. doi:10.1109/TBME.2008.2005955. PMID 19272921.

- ↑ Michael Mireku Kwakye (2011). "A Practical Approach To Merging Multidimensional Data Models".

- ↑ "Rapid Architectural Consolidation Engine – The enterprise solution for disparate data models." (PDF). 2011.

- ↑ "Hub Lake and Warehouse search trends".

- ↑ "A Model Theory for Generic Schema Management".

- ↑ "Nested Mappings: Schema Mapping Reloaded" (PDF).

- ↑ "The Common Framework Initiative for algebraic specification and development of software" (PDF).

- ↑ Christoph Koch (2001). "Data Integration against Multiple Evolving Autonomous Schemata" (PDF).

- ↑ Jeffrey D. Ullman (1997). "Information Integration Using Logical Views". ICDT 1997. pp. 19–40.

- 1 2 3 Alon Y. Halevy (2001). "Answering queries using views: A survey" (PDF). The VLDB Journal. pp. 270–294.

- ↑ William Michener; et al. "DataONE: Observation Network for Earth". www.dataone.org. Retrieved 2013-01-19.

- ↑ Sayeed Choudhury; et al. "Data Conservancy". dataconservancy.org. Retrieved 2013-01-19.

- ↑ Margaret Hedstrom; et al. "SEAD Sustainable Environment - Actionable Data". sead-data.net. Retrieved 2013-01-19.

- ↑ Reagan Moore; et al. "DataNet Federation Consortium". datafed.org. Retrieved 2013-01-19.

- ↑ Steven Ruggles; et al. "Terra Populus: Integrated Data on Population and the Environment". terrapop.org. Retrieved 2013-01-19.

- ↑ Bill Nichols. "Research Data Alliance". rd-alliance.org. Retrieved 2014-10-01.

Further reading

- Ronald Schuldt (November 15, 2011). UDEF – Six Steps to Cost Effective Data Integration. CreateSpace. ISBN 978-1-4664-6762-0.

- Roberta Shauger (December 20, 2011). UDEF Concepts Defined – Reference Guide. CreateSpace. ISBN 978-1-4681-1483-6.