Cultural anthropology

| Anthropology |

|---|

|

Lists

|

|

Cultural anthropology is a branch of anthropology focused on the study of cultural variation among humans and is in contrast to social anthropology which perceives cultural variation as a subset of the anthropological constant.

A variety of methods are part of anthropological methodology, including participant observation (often called fieldwork because it involves the anthropologist spending an extended period of time at the research location), interviews, and surveys.[1]

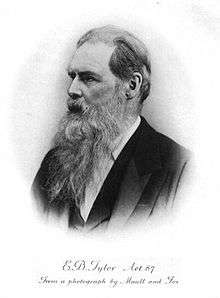

One of the earliest articulations of the anthropological meaning of the term "culture" came from Sir Edward Tylor who writes on the first page of his 1897 book: "Culture, or civilization, taken in its broad, ethnographic sense, is that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society."[2] The term "civilization" later gave way to definitions by V. Gordon Childe, with culture forming an umbrella term and civilization becoming a particular kind of culture.[3]

The anthropological concept of "culture" reflects in part a reaction against earlier Western discourses based on an opposition between "culture" and "nature", according to which some human beings lived in a "state of nature". Anthropologists have argued that culture is "human nature", and that all people have a capacity to classify experiences, encode classifications symbolically (i.e. in language), and teach such abstractions to others.

Since humans acquire culture through the learning processes of enculturation and socialization, people living in different places or different circumstances develop different cultures. Anthropologists have also pointed out that through culture people can adapt to their environment in non-genetic ways, so people living in different environments will often have different cultures. Much of anthropological theory has originated in an appreciation of and interest in the tension between the local (particular cultures) and the global (a universal human nature, or the web of connections between people in distinct places/circumstances).[4]

The rise of cultural anthropology occurred within the context of the late 19th century, when questions regarding which cultures were "primitive" and which were "civilized" occupied the minds of not only Marx and Freud, but many others. Colonialism and its processes increasingly brought European thinkers in contact, directly or indirectly with "primitive others."[5] The relative status of various humans, some of whom had modern advanced technologies that included engines and telegraphs, while others lacked anything but face-to-face communication techniques and still lived a Paleolithic lifestyle, was of interest to the first generation of cultural anthropologists.

Parallel with the rise of cultural anthropology in the United States, social anthropology, in which sociality is the central concept and which focuses on the study of social statuses and roles, groups, institutions, and the relations among them—developed as an academic discipline in Britain and in France.[6] An umbrella term socio-cultural anthropology makes reference to both cultural and social anthropology traditions.[7]

Theoretical foundations

The critique of evolutionism

Anthropology is concerned with the lives of people within different parts of the world, particularly in relation to the discourse of beliefs and practices. In addressing this question, ethnologists in the 19th century divided into two schools of thought. Some, like Grafton Elliot Smith, argued that different groups must somehow have learned from one another, however indirectly; in other words, they argued that cultural traits spread from one place to another, or "diffused".

Other ethnologists argued that different groups had the capability of creating similar beliefs and practices independently. Some of those who advocated "independent invention", like Lewis Henry Morgan, additionally supposed that similarities meant that different groups had passed through the same stages of cultural evolution (See also classical social evolutionism). Morgan, in particular, acknowledged that certain forms of society and culture could not possibly have arisen before others. For example, industrial farming could not have been invented before simple farming, and metallurgy could not have developed without previous non-smelting processes involving metals (such as simple ground collection or mining). Morgan, like other 19th century social evolutionists, believed there was a more or less orderly progression from the primitive to the civilized.

20th-century anthropologists largely reject the notion that all human societies must pass through the same stages in the same order, on the grounds that such a notion does not fit the empirical facts. Some 20th-century ethnologists, like Julian Steward, have instead argued that such similarities reflected similar adaptations to similar environments. Although 19th-century ethnologists saw "diffusion" and "independent invention" as mutually exclusive and competing theories, most ethnographers quickly reached a consensus that both processes occur, and that both can plausibly account for cross-cultural similarities. But these ethnographers also pointed out the superficiality of many such similarities. They noted that even traits that spread through diffusion often were given different meanings and function from one society to another. Analyses of large human concentrations in big cities, in multidisciplinary studies by Ronald Daus, show how new methods may be applied to the understanding of man living in a global world and how it was caused by the action of extra-European nations, so high-lighting the role of Ethics in modern anthropology.

Accordingly, most of these anthropologists showed less interest in comparing cultures, generalizing about human nature, or discovering universal laws of cultural development, than in understanding particular cultures in those cultures' own terms. Such ethnographers and their students promoted the idea of "cultural relativism", the view that one can only understand another person's beliefs and behaviors in the context of the culture in which he or she lived or lives.

Others, such as Claude Lévi-Strauss (who was influenced both by American cultural anthropology and by French Durkheimian sociology), have argued that apparently similar patterns of development reflect fundamental similarities in the structure of human thought (see structuralism). By the mid-20th century, the number of examples of people skipping stages, such as going from hunter-gatherers to post-industrial service occupations in one generation, were so numerous that 19th-century evolutionism was effectively disproved.[8]

Cultural relativism

Cultural relativism is a principle that was established as axiomatic in anthropological research by Franz Boas and later popularized by his students. Boas first articulated the idea in 1887: "...civilization is not something absolute, but ... is relative, and ... our ideas and conceptions are true only so far as our civilization goes."[9] Although, Boas did not coin the term, it became common among anthropologists after Boas' death in 1942, to express their synthesis of a number of ideas Boas had developed. Boas believed that the sweep of cultures, to be found in connection with any sub-species, is so vast and pervasive that there cannot be a relationship between culture and race.[10] Cultural relativism involves specific epistemological and methodological claims. Whether or not these claims require a specific ethical stance is a matter of debate. This principle should not be confused with moral relativism.

Cultural relativism was in part a response to Western ethnocentrism. Ethnocentrism may take obvious forms, in which one consciously believes that one's people's arts are the most beautiful, values the most virtuous, and beliefs the most truthful. Franz Boas, originally trained in physics and geography, and heavily influenced by the thought of Kant, Herder, and von Humboldt, argued that one's culture may mediate and thus limit one's perceptions in less obvious ways. This understanding of culture confronts anthropologists with two problems: first, how to escape the unconscious bonds of one's own culture, which inevitably bias our perceptions of and reactions to the world, and second, how to make sense of an unfamiliar culture. The principle of cultural relativism thus forced anthropologists to develop innovative methods and heuristic strategies.

Theoretical approaches

Foundational thinkers

Boas and his students realized that if they were to conduct scientific research in other cultures, they would need to employ methods that would help them escape the limits of their own ethnocentrism. One such method is that of ethnography: basically, they advocated living with people of another culture for an extended period of time, so that they could learn the local language and be enculturated, at least partially, into that culture.[11][12]

In this context, cultural relativism is of fundamental methodological importance, because it calls attention to the importance of the local context in understanding the meaning of particular human beliefs and activities. Thus, in 1948 Virginia Heyer wrote, "Cultural relativity, to phrase it in starkest abstraction, states the relativity of the part to the whole. The part gains its cultural significance by its place in the whole, and cannot retain its integrity in a different situation."[13]

Lewis Henry Morgan

Lewis Henry Morgan (1818–1881), a lawyer from Rochester, New York, became an advocate for and ethnological scholar of the Iroquois. His comparative analyses of religion, government, material culture, and especially kinship patterns proved to be influential contributions to the field of anthropology. Like other scholars of his day (such as Edward Tylor), Morgan argued that human societies could be classified into categories of cultural evolution on a scale of progression that ranged from savagery, to barbarism, to civilization. Generally, Morgan used technology (such as bowmaking or pottery) as an indicator of position on this scale.

Franz Boas, founder of the modern discipline

Franz Boas established academic anthropology in the United States in opposition to this sort of evolutionary perspective. His approach was empirical, skeptical of overgeneralizations, and eschewed attempts to establish universal laws. For example, Boas studied immigrant children to demonstrate that biological race was not immutable, and that human conduct and behavior resulted from nurture, rather than nature.

Influenced by the German tradition, Boas argued that the world was full of distinct cultures, rather than societies whose evolution could be measured by how much or how little "civilization" they had. He believed that each culture has to be studied in its particularity, and argued that cross-cultural generalizations, like those made in the natural sciences, were not possible.

In doing so, he fought discrimination against immigrants, blacks, and indigenous peoples of the Americas.[14] Many American anthropologists adopted his agenda for social reform, and theories of race continue to be popular subjects for anthropologists today. The so-called "Four Field Approach" has its origins in Boasian Anthropology, dividing the discipline in the four crucial and interrelated fields of sociocultural, biological, linguistic, and archaic anthropology (e.g. archaeology). Anthropology in the United States continues to be deeply influenced by the Boasian tradition, especially its emphasis on culture.

.jpg)

Kroeber, Mead and Benedict

Boas used his positions at Columbia University and the American Museum of Natural History to train and develop multiple generations of students. His first generation of students included Alfred Kroeber, Robert Lowie, Edward Sapir and Ruth Benedict, who each produced richly detailed studies of indigenous North American cultures. They provided a wealth of details used to attack the theory of a single evolutionary process. Kroeber and Sapir's focus on Native American languages helped establish linguistics as a truly general science and free it from its historical focus on Indo-European languages.

The publication of Alfred Kroeber's textbook, Anthropology, marked a turning point in American anthropology. After three decades of amassing material, Boasians felt a growing urge to generalize. This was most obvious in the 'Culture and Personality' studies carried out by younger Boasians such as Margaret Mead and Ruth Benedict. Influenced by psychoanalytic psychologists including Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung, these authors sought to understand the way that individual personalities were shaped by the wider cultural and social forces in which they grew up.

Though such works as Coming of Age in Samoa and The Chrysanthemum and the Sword remain popular with the American public, Mead and Benedict never had the impact on the discipline of anthropology that some expected. Boas had planned for Ruth Benedict to succeed him as chair of Columbia's anthropology department, but she was sidelined by Ralph Linton, and Mead was limited to her offices at the AMNH.

Wolf, Sahlins, Mintz and political economy

In the 1950s and mid-1960s anthropology tended increasingly to model itself after the natural sciences. Some anthropologists, such as Lloyd Fallers and Clifford Geertz, focused on processes of modernization by which newly independent states could develop. Others, such as Julian Steward and Leslie White, focused on how societies evolve and fit their ecological niche—an approach popularized by Marvin Harris.

Economic anthropology as influenced by Karl Polanyi and practiced by Marshall Sahlins and George Dalton challenged standard neoclassical economics to take account of cultural and social factors, and employed Marxian analysis into anthropological study. In England, British Social Anthropology's paradigm began to fragment as Max Gluckman and Peter Worsley experimented with Marxism and authors such as Rodney Needham and Edmund Leach incorporated Lévi-Strauss's structuralism into their work. Structuralism also influenced a number of developments in 1960s and 1970s, including cognitive anthropology and componential analysis.

In keeping with the times, much of anthropology became politicized through the Algerian War of Independence and opposition to the Vietnam War;[15] Marxism became an increasingly popular theoretical approach in the discipline.[16] By the 1970s the authors of volumes such as Reinventing Anthropology worried about anthropology's relevance.

Since the 1980s issues of power, such as those examined in Eric Wolf's Europe and the People Without History, have been central to the discipline. In the 1980s books like Anthropology and the Colonial Encounter pondered anthropology's ties to colonial inequality, while the immense popularity of theorists such as Antonio Gramsci and Michel Foucault moved issues of power and hegemony into the spotlight. Gender and sexuality became popular topics, as did the relationship between history and anthropology, influenced by Marshall Sahlins (again), who drew on Lévi-Strauss and Fernand Braudel to examine the relationship between symbolic meaning, sociocultural structure, and individual agency in the processes of historical transformation. Jean and John Comaroff produced a whole generation of anthropologists at the University of Chicago that focused on these themes. Also influential in these issues were Nietzsche, Heidegger, the critical theory of the Frankfurt School, Derrida and Lacan.[17]

Geertz, Schneider and interpretive anthropology

Many anthropologists reacted against the renewed emphasis on materialism and scientific modelling derived from Marx by emphasizing the importance of the concept of culture. Authors such as David Schneider, Clifford Geertz, and Marshall Sahlins developed a more fleshed-out concept of culture as a web of meaning or signification, which proved very popular within and beyond the discipline. Geertz was to state:

"Believing, with Max Weber, that man is an animal suspended in webs of significance he himself has spun, I take culture to be those webs, and the analysis of it to be therefore not an experimental science in search of law but an interpretive one in search of meaning."— Clifford Geertz[18]

Geertz's interpretive method involved what he called "thick description." The cultural symbols of rituals, political and economic action, and of kinship, are "read" by the anthropologist as if they are a document in a foreign language. The interpretation of those symbols must be re-framed for their anthropological audience, i.e. transformed from the "experience-near" but foreign concepts of the other culture, into the "experience-distant" theoretical concepts of the anthropologist. These interpretations must then be reflected back to its originators, and its adequacy as a translation fine-tuned in a repeated way, a process called the hermeneutic circle. Geertz applied his method in a number of areas, creating programs of study that were very productive. His analysis of "religion as a cultural system" was particularly influential outside of anthropology. David Schnieder's cultural analysis of American kinship has proven equally influential.[19] Schneider demonstrated that the American folk-cultural emphasis on "blood connections" had an undue influence on anthropological kinship theories, and that kinship is not a biological characteristic but a cultural relationship established on very different terms in different societies.[20]

Prominent British symbolic anthropologists include Victor Turner and Mary Douglas.

The post-modern turn

In the late 1980s and 1990s authors such as George Marcus and James Clifford pondered ethnographic authority, in particular how and why anthropological knowledge was possible and authoritative. They were reflecting trends in research and discourse initiated by Feminists in the academy, although they excused themselves from commenting specifically on those pioneering critics.[21] Nevertheless, key aspects of feminist theorizing and methods became de rigueur as part of the 'post-modern moment' in anthropology: Ethnographies became more interpretative and reflexive,[22] explicitly addressing the author's methodology, cultural, gender and racial positioning, and their influence on his or her ethnographic analysis. This was part of a more general trend of postmodernism that was popular contemporaneously.[23] Currently anthropologists pay attention to a wide variety of issues pertaining to the contemporary world, including globalization, medicine and biotechnology, indigenous rights, virtual communities, and the anthropology of industrialized societies.

Socio-cultural anthropology subfields

Methods

Modern cultural anthropology has its origins in, and developed in reaction to, 19th century "ethnology", which involves the organized comparison of human societies. Scholars like E.B. Tylor and J.G. Frazer in England worked mostly with materials collected by others – usually missionaries, traders, explorers, or colonial officials – earning them the moniker of "arm-chair anthropologists".

Participant observation

Participant observation is a widely used methodology in many disciplines, particularly cultural anthropology, less so in sociology, communication studies, and social psychology. Its aim is to gain a close and intimate familiarity with a given group of individuals (such as a religious, occupational, sub cultural group, or a particular community) and their practices through an intensive involvement with people in their cultural environment, usually over an extended period of time. The method originated in the field research of social anthropologists, especially Bronislaw Malinowski in Britain, the students of Franz Boas in the United States, and in the later urban research of the Chicago School of sociology.

Such research involves a range of well-defined, though variable methods: informal interviews, direct observation, participation in the life of the group, collective discussions, analyses of personal documents produced within the group, self-analysis, results from activities undertaken off or online, and life-histories. Although the method is generally characterized as qualitative research, it can (and often does) include quantitative dimensions. Traditional participant observation is usually undertaken over an extended period of time, ranging from several months to many years, and even generations. An extended research time period means that the researcher is able to obtain more detailed and accurate information about the individuals, community, and/or population under study. Observable details (like daily time allotment) and more hidden details (like taboo behavior) are more easily observed and interpreted over a longer period of time. A strength of observation and interaction over extended periods of time is that researchers can discover discrepancies between what participants say—and often believe—should happen (the formal system) and what actually does happen, or between different aspects of the formal system; in contrast, a one-time survey of people's answers to a set of questions might be quite consistent, but is less likely to show conflicts between different aspects of the social system or between conscious representations and behavior.[24]

Ethnography

In the 20th century, most cultural and social anthropologists turned to the crafting of ethnographies. An ethnography is a piece of writing about a people, at a particular place and time. Typically, the anthropologist lives among people in another society for a period of time, simultaneously participating in and observing the social and cultural life of the group.

Numerous other ethnographic techniques have resulted in ethnographic writing or details being preserved, as cultural anthropologists also curate materials, spend long hours in libraries, churches and schools poring over records, investigate graveyards, and decipher ancient scripts. A typical ethnography will also include information about physical geography, climate and habitat. It is meant to be a holistic piece of writing about the people in question, and today often includes the longest possible timeline of past events that the ethnographer can obtain through primary and secondary research.

Bronisław Malinowski developed the ethnographic method, and Franz Boas taught it in the United States. Boas' students such as Alfred L. Kroeber, Ruth Benedict and Margaret Mead drew on his conception of culture and cultural relativism to develop cultural anthropology in the United States. Simultaneously, Malinowski and A.R. Radcliffe Brown´s students were developing social anthropology in the United Kingdom. Whereas cultural anthropology focused on symbols and values, social anthropology focused on social groups and institutions. Today socio-cultural anthropologists attend to all these elements.

In the early 20th century, socio-cultural anthropology developed in different forms in Europe and in the United States. European "social anthropologists" focused on observed social behaviors and on "social structure", that is, on relationships among social roles (for example, husband and wife, or parent and child) and social institutions (for example, religion, economy, and politics).

American "cultural anthropologists" focused on the ways people expressed their view of themselves and their world, especially in symbolic forms, such as art and myths. These two approaches frequently converged and generally complemented one another. For example, kinship and leadership function both as symbolic systems and as social institutions. Today almost all socio-cultural anthropologists refer to the work of both sets of predecessors, and have an equal interest in what people do and in what people say.

Cross-cultural comparison

One means by which anthropologists combat ethnocentrism is to engage in the process of cross-cultural comparison. It is important to test so-called "human universals" against the ethnographic record. Monogamy, for example, is frequently touted as a universal human trait, yet comparative study shows that it is not. The Human Relations Area Files, Inc. (HRAF) is a research agency based at Yale University. Since 1949, its mission has been to encourage and facilitate worldwide comparative studies of human culture, society, and behavior in the past and present. The name came from the Institute of Human Relations, an interdisciplinary program/building at Yale at the time. The Institute of Human Relations had sponsored HRAF’s precursor, the Cross-Cultural Survey (see George Peter Murdock), as part of an effort to develop an integrated science of human behavior and culture. The two eHRAF databases on the Web are expanded and updated annually. eHRAF World Cultures includes materials on cultures, past and present, and covers nearly 400 cultures. The second database, eHRAF Archaeology, covers major archaeological traditions and many more sub-traditions and sites around the world.

Comparison across cultures includies the industrialized (or de-industrialized) West. Cultures in the more traditional standard cross-cultural sample of small scale societies are:

Multi-sited ethnography

Ethnography dominates socio-cultural anthropology. Nevertheless, many contemporary socio-cultural anthropologists have rejected earlier models of ethnography as treating local cultures as bounded and isolated. These anthropologists continue to concern themselves with the distinct ways people in different locales experience and understand their lives, but they often argue that one cannot understand these particular ways of life solely from a local perspective; they instead combine a focus on the local with an effort to grasp larger political, economic, and cultural frameworks that impact local lived realities. Notable proponents of this approach include Arjun Appadurai, James Clifford, George Marcus, Sidney Mintz, Michael Taussig, Eric Wolf and Ronald Daus.

A growing trend in anthropological research and analysis is the use of multi-sited ethnography, discussed in George Marcus' article, "Ethnography In/Of the World System: the Emergence of Multi-Sited Ethnography". Looking at culture as embedded in macro-constructions of a global social order, multi-sited ethnography uses traditional methodology in various locations both spatially and temporally. Through this methodology, greater insight can be gained when examining the impact of world-systems on local and global communities.

Also emerging in multi-sited ethnography are greater interdisciplinary approaches to fieldwork, bringing in methods from cultural studies, media studies, science and technology studies, and others. In multi-sited ethnography, research tracks a subject across spatial and temporal boundaries. For example, a multi-sited ethnography may follow a "thing," such as a particular commodity, as it is transported through the networks of global capitalism.

Multi-sited ethnography may also follow ethnic groups in diaspora, stories or rumours that appear in multiple locations and in multiple time periods, metaphors that appear in multiple ethnographic locations, or the biographies of individual people or groups as they move through space and time. It may also follow conflicts that transcend boundaries. An example of multi-sited ethnography is Nancy Scheper-Hughes' work on the international black market for the trade of human organs. In this research, she follows organs as they are transferred through various legal and illegal networks of capitalism, as well as the rumours and urban legends that circulate in impoverished communities about child kidnapping and organ theft.

Sociocultural anthropologists have increasingly turned their investigative eye on to "Western" culture. For example, Philippe Bourgois won the Margaret Mead Award in 1997 for In Search of Respect, a study of the entrepreneurs in a Harlem crack-den. Also growing more popular are ethnographies of professional communities, such as laboratory researchers, Wall Street investors, law firms, or information technology (IT) computer employees.[25]

See also

- Age-area hypothesis

- Community studies

- Communitas

- Cross-cultural studies

- Cross-cultural psychology

- Cultural psychology

- Cyber anthropology

- Dual inheritance theory

- Engaged theory

- Ethnobotany

- Ethnography

- Ethnomusicology

- Ethnozoology

- Human behavioral ecology

- Human Relations Area Files

- Hunter-gatherers

- Intangible Cultural Heritage

- List of important publications in anthropology

- Nomads

- Poles in mythology

- Shame society vs Guilt society

- Sociology

References

- ↑ "In his earlier work, like many anthropologists of this generation, Levi-Strauss draws attention to the necessary and urgent task of maintaining and extending the empirical foundations of anthropology in the practice of fieldwork.": In Christopher Johnson, Claude Levi-Strauss: the formative years, Cambridge University Press, 2003, p.31

- ↑ Tylor, Edward. 1920 [1871]. Primitive Culture. Vol 1. New York: J.P. Putnam’s Sons.

- ↑ Sherratt, Andrew V. "Gordon Childe: Archaeology and Intellectual History", Past and Present, No. 125.

- ↑ Giulio Angioni (2011). Fare dire sentire: l'identico e il diverso nelle culture. Nuoro: il Maestrale

- ↑ Rosaldo, Renato. Culture and Truth. 1993. Beach Press.

- ↑ Dianteill, Erwan, "Cultural Anthropology or Social Anthropology? A Transatlantic Dispute", L’Année sociologique 1/2012 (Vol. 62), p. 93-122.

- ↑ Campbell, D.T. (1983) The two distinct routes beyond kin selection to ultrasociality: Implications for the Humanities and Social Sciences. In: The Nature of Prosocial Development: Theories and Strategies D. Bridgeman (ed.), pp. 11-39, Academic Press, New York

- ↑ Diamond, Jared. Guns, Germs and Steel.

- ↑ Franz Boas 1887 "Museums of Ethnology and their classification" Science 9: 589

- ↑ http://www.utpa.edu/faculty/mglazer/theory/cultural_relativism.htm

- ↑ Jackson, Anthony. 1987. Anthropology at Home. New York: Tavistock Publications

- ↑ Mughal, Muhammad Aurang Zeb. (2015). Being and Becoming Native: A Methodological Enquiry into Doing Anthropology at Home. Anthropological Notebooks 21(1): 121-132.

- ↑ Heyer, Virginia 1948 "In Reply to Elgin Williams" in American Anthropologist 50(1) 163-166

- ↑ Stocking, George W. (1968) Race, Culture, and Evolution: Essays in the history of anthropology. London: The Free Press.

- ↑ Fanon, Frantz. (1963) The Wretched of the Earth, transl. Constance Farrington. New York, Grove Weidenfeld.

- ↑ Nugent, Stephen Some reflections on anthropological structural Marxism The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, Volume 13, Number 2, June 2007, pp. 419-431(13)

- ↑ Lewis, Herbert S. (1998) The Misrepresentation of Anthropology and its Consequences American Anthropologist 100:" 716-731

- ↑ Geertz, Clifford (1973). The Interpretation of Cultures. Basic Books. p. 5.

- ↑ Roseberry, William (1989). "Balinese Cockfights and the Seduction of Anthropology" in Anthropologies and Histories: essays in culture, history and political economy. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. pp. 17–28.

- ↑ Carsten, Janet (2004). After Kinship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 18–20.

- ↑ Clifford, James and George E. Marcus (1986) Writing culture: the poetics and politics of ethnography. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- ↑ Dolores Janiewski, Lois W. Banner (2005) Reading Benedict / Reading Mead: Feminism, Race, and Imperial Visions, p.200 quotation:

Within anthropology's "two cultures"—the positivist/objectivist style of comparative anthropology versus a reflexive/interpretative anthropology—Mead has been characterized as a "humanist" heir to Franz Boas's historical particularism—hence, associated with the practices of interpretation and reflexivity [...]

- ↑ Gellner, Ernest (1992) Postmodernism, Reason, and Religion. London/New York: Routledge. Pp: 26-50

- ↑ DeWalt, K. M., DeWalt, B. R., & Wayland, C. B. (1998). "Participant observation." In H. R. Bernard (Ed.), Handbook of methods in cultural anthropology. Pp: 259-299. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

- ↑ Dissertation Abstract

External links

- Template:Wikibooks-inlineCultural Anthropology

- Human Relations Area Files

- A Basic Guide to Cross-Cultural Research

- Webpage "History of German Anthropology/Ethnology 1945/49-1990

- The Moving Anthropology Student Network-website - The site offers tutorials, information on the subject, discussion-forums and a large link-collection for all interested scholars of cultural anthropology

- Hungarian military forces in Africa – past and future. Recovering lost knowledge, exploiting cultural anthropology resources, creating a comprehensive system of training and preparation

|