Crystal

A crystal or crystalline solid is a solid material whose constituents, such as atoms, molecules or ions, are arranged in a highly ordered microscopic structure, forming a crystal lattice that extends in all directions. In addition, macroscopic single crystals are usually identifiable by their geometrical shape, consisting of flat faces with specific, characteristic orientations.

The scientific study of crystals and crystal formation is known as crystallography. The process of crystal formation via mechanisms of crystal growth is called crystallization or solidification. The word crystal is derived from the Ancient Greek word κρύσταλλος (krustallos), meaning both “ice” and “rock crystal”,[1] from κρύος (kruos), "icy cold, frost".[2][3]

Examples of large crystals include snowflakes, diamonds, and table salt. Most inorganic solids are not crystals but polycrystals, i.e. many microscopic crystals fused together into a single solid. Examples of polycrystals include most metals, rocks, ceramics, and ice. A third category of solids is amorphous solids, where the atoms have no periodic structure whatsoever. Examples of amorphous solids include glass, wax, and many plastics.

Crystal structure (microscopic)

The scientific definition of a "crystal" is based on the microscopic arrangement of atoms inside it, called the crystal structure. A crystal is a solid where the atoms form a periodic arrangement. (Quasicrystals are an exception, see below.)

Not all solids are crystals. For example, when liquid water starts freezing, the phase change begins with small ice crystals that grow until they fuse, forming a polycrystalline structure. In the final block of ice, each of the small crystals (called "crystallites" or "grains") is a true crystal with a periodic arrangement of atoms, but the whole polycrystal does not have a periodic arrangement of atoms, because the periodic pattern is broken at the grain boundaries. Most macroscopic inorganic solids are polycrystalline, including almost all metals, ceramics, ice, rocks, etc. Solids that are neither crystalline nor polycrystalline, such as glass, are called amorphous solids, also called glassy, vitreous, or noncrystalline. These have no periodic order, even microscopically. There are distinct differences between crystalline solids and amorphous solids: most notably, the process of forming a glass does not release the latent heat of fusion, but forming a crystal does.

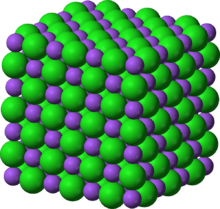

A crystal structure (an arrangement of atoms in a crystal) is characterized by its unit cell, a small imaginary box containing one or more atoms in a specific spatial arrangement. The unit cells are stacked in three-dimensional space to form the crystal.

The symmetry of a crystal is constrained by the requirement that the unit cells stack perfectly with no gaps. There are 219 possible crystal symmetries, called crystallographic space groups. These are grouped into 7 crystal systems, such as cubic crystal system (where the crystals may form cubes or rectangular boxes, such as halite shown at right) or hexagonal crystal system (where the crystals may form hexagons, such as ordinary water ice).

Crystal faces and shapes

Crystals are commonly recognized by their shape, consisting of flat faces with sharp angles. These shape characteristics are not necessary for a crystal—a crystal is scientifically defined by its microscopic atomic arrangement, not its macroscopic shape—but the characteristic macroscopic shape is often present and easy to see.

Euhedral crystals are those with obvious, well-formed flat faces. Anhedral crystals do not, usually because the crystal is one grain in a polycrystalline solid.

The flat faces (also called facets) of a euhedral crystal are oriented in a specific way relative to the underlying atomic arrangement of the crystal: They are planes of relatively low Miller index.[4] This occurs because some surface orientations are more stable than others (lower surface energy). As a crystal grows, new atoms attach easily to the rougher and less stable parts of the surface, but less easily to the flat, stable surfaces. Therefore, the flat surfaces tend to grow larger and smoother, until the whole crystal surface consists of these plane surfaces. (See diagram on right.)

One of the oldest techniques in the science of crystallography consists of measuring the three-dimensional orientations of the faces of a crystal, and using them to infer the underlying crystal symmetry.

A crystal's habit is its visible external shape. This is determined by the crystal structure (which restricts the possible facet orientations), the specific crystal chemistry and bonding (which may favor some facet types over others), and the conditions under which the crystal formed.

Occurrence in nature

Rocks

By volume and weight, the largest concentrations of crystals in the Earth are part of its solid bedrock. Crystals found in rocks typically range in size from a fraction of a millimetre to several centimetres across, although exceptionally large crystals are occasionally found. As of 1999, the world's largest known naturally occurring crystal is a crystal of beryl from Malakialina, Madagascar, 18 m (59 ft) long and 3.5 m (11 ft) in diameter, and weighing 380,000 kg (840,000 lb).[5]

Some crystals have formed by magmatic and metamorphic processes, giving origin to large masses of crystalline rock. The vast majority of igneous rocks are formed from molten magma and the degree of crystallization depends primarily on the conditions under which they solidified. Such rocks as granite, which have cooled very slowly and under great pressures, have completely crystallized; but many kinds of lava were poured out at the surface and cooled very rapidly, and in this latter group a small amount of amorphous or glassy matter is common. Other crystalline rocks, the metamorphic rocks such as marbles, mica-schists and quartzites, are recrystallized. This means that they were at first fragmental rocks like limestone, shale and sandstone and have never been in a molten condition nor entirely in solution, but the high temperature and pressure conditions of metamorphism have acted on them by erasing their original structures and inducing recrystallization in the solid state.[6]

Other rock crystals have formed out of precipitation from fluids, commonly water, to form druses or quartz veins. The evaporites such as halite, gypsum and some limestones have been deposited from aqueous solution, mostly owing to evaporation in arid climates.

Ice

Water-based ice in the form of snow, sea ice and glaciers is a very common manifestation of crystalline or polycrystalline matter on Earth. A single snowflake is typically a single crystal, while an ice cube is a polycrystal.

Organigenic crystals

Many living organisms are able to produce crystals, for example calcite and aragonite in the case of most molluscs or hydroxylapatite in the case of vertebrates.

Polymorphism and allotropy

The same group of atoms can often solidify in many different ways. Polymorphism is the ability of a solid to exist in more than one crystal form. For example, water ice is ordinarily found in the hexagonal form Ice Ih, but can also exist as the cubic Ice Ic, the rhombohedral ice II, and many other forms. The different polymorphs are usually called different phases.

In addition, the same atoms may be able to form noncrystalline phases. For example, water can also form amorphous ice, while SiO2 can form both fused silica (an amorphous glass) and quartz (a crystal). Likewise, if a substance can form crystals, it can also form polycrystals.

For pure chemical elements, polymorphism is known as allotropy. For example, diamond and graphite are two crystalline forms of carbon, while amorphous carbon is a noncrystalline form. Polymorphs, despite having the same atoms, may have wildly different properties. For example, diamond is among the hardest substances known, while graphite is so soft that it is used as a lubricant.

Polyamorphism is a similar phenomenon where the same atoms can exist in more than one amorphous solid form.

Crystallization

Crystallization is the process of forming a crystalline structure from a fluid or from materials dissolved in a fluid. (More rarely, crystals may be deposited directly from gas; see thin-film deposition and epitaxy.)

Crystallization is a complex and extensively-studied field, because depending on the conditions, a single fluid can solidify into many different possible forms. It can form a single crystal, perhaps with various possible phases, stoichiometries, impurities, defects, and habits. Or, it can form a polycrystal, with various possibilities for the size, arrangement, orientation, and phase of its grains. The final form of the solid is determined by the conditions under which the fluid is being solidified, such as the chemistry of the fluid, the ambient pressure, the temperature, and the speed with which all these parameters are changing.

Specific industrial techniques to produce large single crystals (called boules) include the Czochralski process and the Bridgman technique. Other less exotic methods of crystallization may be used, depending on the physical properties of the substance, including hydrothermal synthesis, sublimation, or simply solvent-based crystallization.

Large single crystals can be created by geological processes. For example, selenite crystals in excess of 10 meters are found in the Cave of the Crystals in Naica, Mexico.[7] For more details on geological crystal formation, see above.

Crystals can also be formed by biological processes, see above. Conversely, some organisms have special techniques to prevent crystallization from occurring, such as antifreeze proteins.

Defects, impurities, and twinning

An ideal crystal has every atom in a perfect, exactly repeating pattern. However, in reality, most crystalline materials have a variety of crystallographic defects, places where the crystal's pattern is interrupted. The types and structures of these defects may have a profound effect on the properties of the materials.

A few examples of crystallographic defects include vacancy defects (an empty space where an atom should fit), interstitial defects (an extra atom squeezed in where it does not fit), and dislocations (see figure at right). Dislocations are especially important in materials science, because they help determine the mechanical strength of materials.

Another common type of crystallographic defect is an impurity, meaning that the "wrong" type of atom is present in a crystal. For example, a perfect crystal of diamond would only contain carbon atoms, but a real crystal might perhaps contain a few boron atoms as well. These boron impurities change the diamond's color to slightly blue. Likewise, the only difference between ruby and sapphire is the type of impurities present in a corundum crystal.

In semiconductors, a special type of impurity, called a dopant, drastically changes the crystal's electrical properties. Semiconductor devices, such as transistors, are made possible largely by putting different semiconductor dopants into different places, in specific patterns.

Twinning is a phenomenon somewhere between a crystallographic defect and a grain boundary. Like a grain boundary, a twin boundary has different crystal orientations on its two sides. But unlike a grain boundary, the orientations are not random, but related in a specific, mirror-image way.

Mosaicity is a spread of crystal plane orientations. A mosaic crystal is supposed to consist of smaller crystalline units that are somewhat misaligned with respect to each other.

Chemical bonds

Crystalline structures occur in all classes of materials, with all types of chemical bonds. Almost all metal exists in a polycrystalline state; amorphous or single-crystal metals must be produced synthetically, often with great difficulty. Ionically bonded crystals can form upon solidification of salts, either from a molten fluid or upon crystallization from a solution. Covalently bonded crystals are also very common, notable examples being diamond, silica, and graphite. Polymer materials generally will form crystalline regions, but the lengths of the molecules usually prevent complete crystallization. Weak van der Waals forces can also play a role in a crystal structure; for example, this type of bonding loosely holds together the hexagonal-patterned sheets in graphite.

Properties

| Crystal | Particles | Attractive forces | Melting point | Other properties |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ionic | Positive and negative ions | Electrostatic attractions | High | Hard, brittle, good electrical conductor in molten state |

| Molecular | Polar molecules | London force and dipole-dipole attraction | Low | Soft, non-conductor or extremely poor conductor of electricity in liquid state |

| Molecular | Non-polar molecules | London force | Low | Soft conductor |

Quasicrystals

A quasicrystal consists of arrays of atoms that are ordered but not strictly periodic. They have many attributes in common with ordinary crystals, such as displaying a discrete pattern in x-ray diffraction, and the ability to form shapes with smooth, flat faces.

Quasicrystals are most famous for their ability to show five-fold symmetry, which is impossible for an ordinary periodic crystal (see crystallographic restriction theorem).

The International Union of Crystallography has redefined the term "crystal" to include both ordinary periodic crystals and quasicrystals ("any solid having an essentially discrete diffraction diagram"[8]).

Quasicrystals, first discovered in 1982, are quite rare in practice. Only about 100 solids are known to form quasicrystals, compared to about 400,000 periodic crystals measured to date.[9] The 2011 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to Dan Shechtman for the discovery of quasicrystals.[10]

Special properties from anisotropy

Crystals can have certain special electrical, optical, and mechanical properties that glass and polycrystals normally cannot. These properties are related to the anisotropy of the crystal, i.e. the lack of rotational symmetry in its atomic arrangement. One such property is the piezoelectric effect, where a voltage across the crystal can shrink or stretch it. Another is birefringence, where a double image appears when looking through a crystal. Moreover, various properties of a crystal, including electrical conductivity, electrical permittivity, and Young's modulus, may be different in different directions in a crystal. For example, graphite crystals consist of a stack of sheets, and although each individual sheet is mechanically very strong, the sheets are rather loosely bound to each other. Therefore, the mechanical strength of the material is quite different depending on the direction of stress.

Not all crystals have all of these properties. Conversely, these properties are not quite exclusive to crystals. They can appear in glasses or polycrystals that have been made anisotropic by working or stress—for example, stress-induced birefringence.

Crystallography

Crystallography is the science of measuring the crystal structure (in other words, the atomic arrangement) of a crystal. One widely used crystallography technique is X-ray diffraction. Large numbers of known crystal structures are stored in crystallographic databases.

Gallery

-

Insulin crystals grown in earth orbit.

-

Hoar frost: A type of ice crystal (picture taken from a distance of about 5 cm).

-

Gallium, a metal that easily forms large crystals.

-

An apatite crystal sits front and center on cherry-red rhodochroite rhombs, purple fluorite cubes, quartz and a dusting of brass-yellow pyrite cubes.

-

Boules of silicon, like this one, are an important type of industrially-produced single crystal.

-

A specimen consisting of a bornite-coated chalcopyrite crystal nestled in a bed of clear quartz crystals and lustrous pyrite crystals. The bornite-coated crystal is up to 1.5 cm across.

See also

- Atomic packing factor

- Anticrystal

- Cocrystal

- Colloidal crystal

- Crystal growth

- Crystal oscillator

- Liquid crystal

References

- ↑ κρύσταλλος, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- ↑ κρύος, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- ↑ "The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language". Kreus. 2000.

- ↑ The surface science of metal oxides, by Victor E. Henrich, P. A. Cox, page 28, google books link

- ↑ G. Cressey and I. F. Mercer, (1999) Crystals, London, Natural History Museum, page 58

- ↑

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Petrology". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Petrology". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. - ↑ "Cave of Crystal Giants — National Geographic Magazine". nationalgeographic.com.

- ↑ International Union of Crystallography (1992). "Report of the Executive Committee for 1991". Acta Crystallogr. A 48 (6): 922. doi:10.1107/S0108767392008328.

- ↑ Steurer W. (2004). "Twenty years of structure research on quasicrystals. Part I. Pentagonal, octagonal, decagonal and dodecagonal quasicrystals". Z. Kristallogr. 219 (7–2004): 391–446. Bibcode:2004ZK....219..391S. doi:10.1524/zkri.219.7.391.35643.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2011". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 2011-12-29.

Further reading

- Howard, J. Michael; Darcy Howard (Illustrator) (1998). "Introduction to Crystallography and Mineral Crystal Systems". Bob's Rock Shop. Retrieved 2008-04-20.

- Krassmann, Thomas (2005–2008). "The Giant Crystal Project". Krassmann. Retrieved 2008-04-20.

- Various authors (2007). "Teaching Pamphlets". Commission on Crystallographic Teaching. Retrieved 2008-04-20.

- Various authors (2004). "Crystal Lattice Structures:Index by Space Group". U.S. Naval Research Laboratory, Center for Computational Materials Science. Retrieved 2008-04-20.

- Various authors (2010). "Crystallography". Spanish National Research Council, Department of Crystallography. Retrieved 2010-01-08.

|