Sign of the cross

The sign of the cross (Latin: signum crucis), or blessing oneself or crossing oneself, is a ritual blessing made by members of some branches of Christianity. This blessing is made by the tracing of an upright cross or + across the body with the right hand, often accompanied by spoken or mental recitation of the trinitarian formula.

The motion is the tracing of the shape of a cross in the air or on one's own body, echoing the traditional shape of the cross of the Christian Crucifixion narrative. There are two principal forms: one—three fingers, right to left—is exclusively used in the Eastern Orthodox churches and the Eastern Rites of the Catholic Church of the Byzantine and Chaldean Tradition; the other—left to right, other than three fingers—is the one used in the Latin Rite of the Catholic Church, Anglicanism, Methodism, Lutheranism and Oriental Orthodoxy (see below). The ritual is rare within other Christian traditions.

Many individuals use the expression "cross my heart and hope to die" as an oath, making the sign of the cross, in order to show "truthfulness and sincerity" in both personal and legal situations.[1]

Origins

Christians view the Cross as a symbol representing Christ’s victory over sin and death.[2] The sign of the cross was originally made in some parts of the Christian world with the right-hand thumb across the forehead only (this can still be seen at a Catholic Mass, where the gesture is made at the proclamation of the Gospel).[3] In other parts of the early Christian world it was done with the whole hand or with two fingers.[4] Around the year 200 in Carthage (modern Tunisia, Africa), Tertullian says: "We Christians wear out our foreheads with the sign of the cross".[5] Vestiges of this practice remain: some Christians sign a cross on their forehead before hearing the Gospels during Mass; on Ash Wednesday a cross is traced in ashes on the forehead; holy oil (called chrism) is applied on the forehead for the sacrament of Confirmation (in the East, the Holy Mystery of Chrismation, as Orthodox call the Sacraments by the name "Holy Mystery"). By the 4th century, the sign of the cross involved other parts of the body beyond the forehead.

Gesture

The open right hand is used in Western Christianity. The five open fingers are often said to represent the Five Wounds of Christ.[6] This symbolism was adopted after the more ancient gesture of two or three fingers was simplified. Though this is the most common method of crossing by Western Christians, other forms are sometimes used. The West also employs the "Small Sign of the Cross" (+). The primary use for this is immediately before the reading of The Gospel during the Mass. Using the right thumb, a small cross is traced over the forehead, lips, and heart of the individual while whispering or silently praying the words "May Christ's words be on my mind, on my lips, and in my heart." The Small Sign is also used during the majority of the Sacraments.

In the Roman or Latin Rite Church it is customary to make the full Sign of the Cross using holy water when entering a church. The first three fingers of the right hand are dipped into the font containing the holy water and the Sign of the Cross is made on oneself. This gesture has a two-fold purpose: to remind one of their baptism and the rights and responsibilities that go with it and to also remind one that they are entering a very sacred space that is set apart from the world outside.

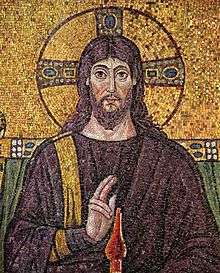

In the Eastern Orthodox (including the Russian Orthodox) and Eastern Catholic Churches, the tips of the first three fingers (the thumb, index, and middle ones) are brought together, and the last two (the “ring” and little fingers) are pressed against the palm. The first three fingers express our faith in the Trinity, while the remaining two fingers represent the two natures of Jesus, divine and human.[2]

_detail_01.jpg)

In Russia, until the reforms of Patriarch Nikon in the 17th century, it was customary to make the sign of the cross with two fingers (symbolising the dual nature of Christ). The enforcement of the three-finger sign was one of the reasons for the schism with the Old Believers whose congregations continue to use the two-finger sign of the cross.

The Oriental Orthodox (Armenians, Copts, Ethiopians etc.) generally use the "Western" direction as well, though often with the Byzantine finger formation.

- Motion

The sign of the cross is made by touching the hand sequentially to the forehead, lower chest or stomach, and both shoulders, accompanied by the Trinitarian formula: at the forehead In the name of the Father (or In nomine Patris in Latin); at the stomach or heart and of the Son (et Filii); across the shoulders and of the Holy Spirit/Ghost (et Spiritus Sancti); and finally: Amen.[7]

There are several interpretations, according to Church Fathers:[8] the forehead symbolizes Heaven; the stomach, the earth; the shoulders, the place and sign of power. It also recalls both the Trinity and the Incarnation. Pope Innocent III (1198–1216) explained: "The sign of the cross is made with three fingers, because the signing is done together with the invocation of the Trinity. ... This is how it is done: from above to below, and from the right to the left, because Christ descended from the heavens to the earth..."[6] [9]

There are some variations: for example a person may first place the right hand in holy water. After moving the hand from one shoulder to the other, it may be returned to the stomach. It may also be accompanied by the recitation of a prayer (e.g., the Jesus Prayer, or simply "Lord have mercy"). In some countries, like Spain, Italy and other Latin countries, it is customary to kiss one's thumb at the conclusion of the gesture,[10] while in the Philippines, this extra step evolved into the thumb quickly touching the chin or lower lip.

- Sequence

Theodoret (393–457) gave the following instruction:

This is how to bless someone with your hand and make the sign of the cross over them. Hold three fingers, as equals, together, to represent the Trinity: God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Ghost. These are not three gods, but one God in Trinity. The names are separate, but the divinity one. The Father was never incarnate; the Son incarnate, but not created; the Holy Ghost neither incarnate nor created, but issued from the Godhead: three in a single divinity. Divinity is one force and has one honor. They receive on obeisance from all creation, both angels and people. Thus the decree for these three fingers.

You should hold the other two fingers slightly bent, not completely straight. This is because these represent the dual nature of Christ, divine and human. God in His divinity, and human in His incarnation, yet perfect in both. The upper finger represents divinity, and the lower humanity; this way salvation goes from the higher finger to the lower. So is the bending of the fingers interpreted, for the worship of Heaven comes down for our salvation. This is how you must cross yourselves and give a blessing, as the holy fathers have commanded.

Peter of Damascus (12th century) gave the following instruction:

Then we should also marvel how demons and various diseases are dispelled by the sign of the precious and life-giving Cross, which all can make without cost or effort. Who can number the panegyrics composed in its honor? The holy fathers have handed down to us the inner significance of this sign, so that we can refute heretics and unbelievers. The two fingers and single hand with which it is made represent the Lord Jesus Christ crucified, and He is thereby acknowledged to exist in two natures and one hypostasis or person.

The use of the right hand betokens His infinite power and the fact that He sits at the right hand of the Father. That the sign begins with a downward movement from above signifies His descent to us from heaven. Again, the movement of the hand from the right side to the left drives away our enemies and declares that by His invincible power the Lord overcame the devil, who is on the left side, dark and lacking strength.

Historian Herbert Thurston interprets this as indicating that at one time both Eastern and Western Christians moved the hand from the right shoulder to the left, although the point is not entirely clear. German theologian, Valentin Thalhofer, thought writings quoted in support of this, such as that of Innocent III, refer to the small cross made upon the forehead or external objects, in which the hand moves naturally from right to left, and not the big cross made from shoulder to shoulder.[3] Andreas Andreopoulos, author of The Sign of the Cross, gives a more detailed description of the development and the symbolism of the placement of the fingers and the direction of the movement.[11]

Today, Western Christians and the Oriental Orthodox touch the left shoulder before the right. Eastern Catholics and Orthodox Christians use the right-to-left movement.

The proper sequence of tracing the sign of the cross is taught to converts from Christian denominations that are either nontrinitarian or not using the gesture and non-Christian religions.

Use

The sign of the cross may be made by individuals upon themselves as a form of prayer and by clergy upon others or objects as an act of blessing. The gesture of blessing is certainly related to the sign of the cross, but the two gestures developed independently after some point. In Eastern Christianity, the two gestures differ significantly. Priests and deacons are allowed to bless using the right hand, while bishops may bless simultaneously with both, the left mirroring the right. While individuals may make it at any time, clergy must make it at specific times (as in liturgies), and it is customary to make it on other occasions.

Although the sign of the cross dates to ante-Nicene Christianity, it was rejected by some of the Reformers, and is absent from some forms of Protestantism, although other forms of Protestantism, such as the Anglican Church, Lutheran Church, and United Methodist Church use it. However, it has often been rejected by some Non-Conformist Protestants as being a High Church practice, despite Martin Luther's positive personal view. The prescribed use of the sign in Book of Common Prayer and the defence of the sign of the cross were established in Anglican canon law in 1604.

Some Christians make the sign of the cross in response to perceived blasphemy. Others sign themselves to seek God's blessing before or during an event with uncertain outcome. In Hispanic countries, people often sign themselves in public, such as athletes who cross themselves before entering the field or while concentrating for competition.

In societies with constant Christian observance the sign of the cross is employed during everyday activities. For example, the spoon crosses the newly poured mixture before stirring, housewives bless food when placing it in the oven, potters bless the clay before creating a vessel, and one slicing bread crosses the bread with the knife before cutting, as bread is evocative of the altar bread that represents the body of Christ.

Catholicism

The Sign of the Cross is a prayer, a blessing, and a sacramental. As a sacramental, it prepares an individual to receive grace and disposes one to cooperate with it.[12] The Christian begins his day, his prayers, and his activities with the Sign of the Cross: “In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.” In this way a person dedicates the day to God and calls on him for strength in temptations and difficulties.[13]

Liturgical

Roman Catholicism draws a distinction between liturgical and non-liturgical use of the sign of the cross. The sign of the cross is required at certain points of the Mass: the laity sign themselves during the introductory greeting of the service, before the Gospel reading (small signs on forehead, lips, and heart), and at the final blessing; optionally, other times during the Mass when the laity often cross themselves are during a blessing with holy water, when concluding the penitential rite, immediately after receiving Communion, and when concluding private prayer after Communion. In the ordinary form of the Roman Rite the priest signs bread and wine once before the consecration. In the Tridentine Mass the priest signs the bread and wine 25 times during the Canon of the Mass, ten times before and fifteen times after they have been consecrated. The priest also uses the sign of the cross when blessing a deacon before the deacon reads the Gospel, when sending an Extraordinary Minister of Holy Communion to take the Eucharist to the sick (after Communion, but before the end of the Mass), and when blessing the congregation at the conclusion of the Mass.

Ordained bishops, priests and deacons have more empowerment to bless objects and other people. While lay people may preside at certain blessings, the more a blessing is concerned with eccesial or sacramental matters, the more it is reserved to clergy.[14] Extraordinary ministers of Holy Communion do not ordinarily have a commission to bless in the name of the Church, as priests and deacons do. At this point in the liturgy, their specific function is to assist the clergy in the distribution of holy Communion.[15] Extraordinary Ministers of Communion, blessing those who do not wish to or cannot receive communion can speak or raise the hand but not make the sign of the cross over the person.[16]

Non-liturgical

A priest or deacon blesses an object or person with a single sign of the cross, but a bishop blesses with a triple sign of the cross. In the Catholic organization, the Legion of Mary, members doing door to door parish surveys bless the homes of those not home by tracing the sign of the cross on the door.[17]

Eastern Orthodoxy

In the Eastern traditions, both celebrant and congregation make the sign of the cross much more frequently than in Western Christianity. It is customary in some Eastern traditions to cross oneself at each petition in a litany and to closely associate oneself with a particular intention being prayed for or with a saint being named. The sign of the cross is also made upon entering or leaving a church building, at the start and end of personal prayer, when passing the main altar (which represents Christ), whenever all three persons of the Trinity are addressed, and when approaching an icon.

When an Eastern Orthodox or Eastern Catholic bishop or priest blesses with the sign of the cross, he holds the fingers of his right hand in such a way that they form the Greek abbreviation for Jesus Christ "IC XC". The index finger is extended to make the "I"; the middle finger signify letter "C"; the thumb touches the lowered third finger to signify the "X" and the little finger also signifies the letter "C".[18] When a priest blesses in the sign of the cross, he positions the fingers of his right hand in the manner described as he raises his right hand, then moves his hand downwards, then to his left, then to his right. A bishop blesses with both hands (unless he is holding some sacred object such as a cross, chalice, Gospel Book, icon, etc.), holding the fingers of both hands in the same configuration, but when he moves his right hand to the left, he simultaneously moves his left hand to the right, so that the two hands cross, the left in front of the right, and then the right in front of the left. The blessing of both priests and bishops consists of three movements, in honour of the Holy Trinity.

Lutheranism

Among Lutherans the practice was widely retained. For example, Luther's Small Catechism states that it is expected before the morning and evening prayers. Lutheranism never abandoned the practice of making the sign of the cross in principle and it was commonly retained in worship at least until the early 19th century. During the 19th and early 20th centuries it was largely in disuse until the liturgical renewal movement of the 1950s and 1960s. One exception is The Lutheran Hymnal of 1941,[19] which states that "The sign of the cross may be made at the Trinitarian Invocation and at the words of the Nicene Creed 'and the life of the world to come.'" Since then, the sign of the cross has become fairly commonplace among Lutherans at worship. The sign of the cross is now customary in the Divine Service.[20][21] Rubrics in Contemporary Lutheran worship manuals, including Evangelical Lutheran Worship[22] and Lutheran Service Book,[23] provide for making the sign of the cross at certain points in the liturgy. Most places are the same as the Roman Catholic practice, such as at the trinitarian formula, the benediction, at the consecration of the Eucharist, and following reciting the Nicene or Apostles' Creed.

Devotional use of the sign of the cross among Lutherans also includes after receiving the Host and Chalice in the Eucharist, following Holy Absolution; similarly, they may dip their hands in the baptismal font and make the sign of the cross upon entering the church.

Methodism

The sign of the cross is in the Methodist liturgy and is made by many clergy during the Great Thanksgiving, Confession of Sin and Pardon, and benediction.[24][25] John Wesley, the principal leader of the early Methodists, prepared a revision of The Book of Common Prayer for Methodist use called The Sunday Service of the Methodists in North America which does instruct the minister to make the sign of the cross on the forehead of children just after they have been baptized.[26] Making the sign of the cross at baptism is retained in the current Book of Worship, and widely practiced (sometimes with oil).[27] Furthermore, on Ash Wednesday the sign of the cross is almost always applied by the elder to the foreheads of the laity.[28] The liturgy for healing and wholeness, which is becoming more commonly practiced, calls for the pastor to make the sign of the cross with oil upon the foreheads of those seeking healing.[29]

Whether or not a Methodist uses the sign for private prayer is a personal choice, but it is encouraged by the bishops of the United Methodist Church.[25] Some United Methodists also perform the sign before and after receiving Holy Communion, and some ministers also perform the sign when blessing the congregation at the end of the sermon or service.[30]

Reformed tradition

In some Reformed churches, such as the PCUSA and the Cumberland Presbyterian Church, the sign of the cross is used on the foreheads during baptism[31] or during an Ash Wednesday service when ashes are imposed on the forehead. The sign of the cross in some instances is used during Communion. In some instances during a Benediction, when the minister concludes the service using the trinitarian blessing, a hand is extended and a sign of the cross is made out toward the congregation. This type of benediction is seen in quite a few High Presbyterian groups such as the Church of Scotland and some congregations along the East Coast of the United States.

Armenian Apostolic

It is common practice in the Armenian Apostolic Church to make the sign of the cross when entering a church or during the start of service. The motion is performed by joining the first three fingers and touching one's forehead, below the chest, left side, and then right side.[32][33]

See also

- Benediction

- Christian cross

- Christian symbolism

- Prayer in Christianity

- Sacramentals

- Trinitarian formula

- Veneration

References

- ↑ Ayto, John (8 July 2010). Oxford Dictionary of English Idioms. Oxford University Press. p. 79. ISBN 9780199543786.

- 1 2 Slobodskoy, Serafim Alexivich. "The Sign of the Cross", St. John Chrysostom Orthodox Church, House Springs, Missouri

- 1 2 Thurston, Herbert. "Sign of the Cross." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 13. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912. 20 Jan. 2015

- ↑ Andreas Andreopoulos, The Sign of the Cross, Paraclete Press, 2006, ISBN 978-1-55725-496-2, p. 24.

- ↑ Marucchi, Orazio. "Archæology of the Cross and Crucifix." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908. 20 Jan. 2015

- 1 2 Beale, Stephen. "21 Things We Do When We Make the Sign of the Cross", Catholic Exchange, November 11, 2013

- ↑ Sullivan, John F., The Externals of the Catholic Church, P.J. Kenedy & Sons (1918)

- ↑ Prayer Book, edited by the Romanian Orthodox Church, several editions (Carte de rugăciuni - Editura Institutului biblic şi de misiune al Bisericii ortodoxe române, 2005),

- ↑ "Est autem signum crucis tribus digitis exprimendum, quia sub invocatione Trinitatis imprimitur, de qua dicit propheta: Quis appendit tribus digitis molem terrae? (Isa. XL.) ita quod a superiori descendat in inferius, et a dextra transeat ad sinistram, quia Christus de coelo descendit in terram, et a Judaeis transivit ad gentes. Quidam tamen signum crucis a sinistra producunt in dextram; quia de miseria transire debemus ad gloriam, sicut et Christus transivit de morte ad vitam, et de inferno ad paradisum, praesertim ut seipsos et alios uno eodemque pariter modo consignent. Constat autem quod cum super alios signum crucis imprimimus, ipsos a sinistris consignamus in dextram. Verum si diligenter attendas, etiam super alios signum crucis a dextra producimus in sinistram, quia non consignamus eos quasi vertentes dorsum, sed quasi faciem praesentantes." (Innocentius III, De sacro altaris mysterio, II, xlv in Patrologia Latina 217, 825C--D.)

- ↑ Patricia Ann Kasten, Linking Your Beads: The Rosary's History, Mysteries, and Prayers, Our Sunday Visitor 2011, p. 34

- ↑ Andreas Andreopoulos, The Sign of the Cross, Paraclete Press, 2006, ISBN 978-1-55725-496-2, pp. 11-42.

- ↑ "Sacramentals", Catechism of the Catholic Church, §1670

- ↑ CCC §2157

- ↑ CCC, §1669

- ↑ McNamara, Edward, "Blessings for Non-Communicants", Zenit, 10 May 2005

- ↑ Archdiocesan Manual for Parish Trainers of Extraordinary Ministers of Communion, Archdiocese of Atlanta

- ↑ Legion of Mary Handbook

- ↑ "The Sign of the Cross", St. Elias the Prophet Church, Eparchy of Toronto and Eastern Canada

- ↑ Concordia Publishing House: St. Louis, page 4.

- ↑ "Why Do Lutherans Make the Sign of the Cross?". Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. Retrieved 2007-06-16.

- ↑ "Sign of the Cross". Lutheran Church - Missouri Synod. Archived from the original on September 20, 2005. Retrieved 2007-09-12.

- ↑ Minneapolis:Augsburg Fortress, 2006

- ↑ St. Louis: Concordia, 2006

- ↑ Neal, Gregory S. (2011). "Prepared and Cross-Checked". Grace Incarnate Ministries. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- 1 2 "Can United Methodists use the sign of the cross?". United Methodist Church. Retrieved 2007-06-16.

- ↑ John Wesley's Prayer Book: The Sunday Service of the Methodists in North America with introduction, notes, and commentary by James F. White, 1991 OSL Publications, Akron, Ohio, page 142.

- ↑ The United Methodist Book of Worship, Nashville 1992, p. 91

- ↑ The United Methodist Book of Worship, Nashville 1992, p. 323.

- ↑ The United Methodist Book of Worship, Nashville 1992, p. 620.

- ↑ "What is the significance of ashes being placed on the forehead on Ash Wednesday?". Retrieved 2007-06-16.

- ↑ Understanding Baptism, First Presbyterian Church of Crestview and Laurel Hill, Florida.

- ↑ "Making the Sign of the Cross (Khachaknkel)". Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ↑ "In the Shadow of the Cross: The Holy Cross and Armenian History". Retrieved 6 December 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sign of the cross. |

- Catholic

- "Sacramentals", Catechism of the Catholic Church

- Thurston, Herbert. "The Cross and Crucifix in Liturgy." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908.

- Ghezzi, Bert. "Significance of the Sign of the Cross"

- Orthodox

- Sign of the Cross (orthodoxwiki.org)

- Why do Orthodox Christians "cross themselves" different than Roman Catholics?

- The Church Council of the Hundred Chapters(1551) (Old Believers)

- Protestant

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||