Cronbach's alpha

In statistics (Classical Test Theory), Cronbach's  (alpha)[1] is used as a (lowerbound) estimate of the reliability of a psychometric test.

(alpha)[1] is used as a (lowerbound) estimate of the reliability of a psychometric test.

It has been proposed that  can be viewed as the expected correlation of two tests that measure the same construct. By using this definition, it is implicitly assumed that the average correlation of a set of items is an accurate estimate of the average correlation of all items that pertain to a certain construct.[2]

can be viewed as the expected correlation of two tests that measure the same construct. By using this definition, it is implicitly assumed that the average correlation of a set of items is an accurate estimate of the average correlation of all items that pertain to a certain construct.[2]

Cronbach's  is a function of the number of items in a test, the average covariance between item-pairs, and the variance of the total score.

is a function of the number of items in a test, the average covariance between item-pairs, and the variance of the total score.

It was first named alpha by Lee Cronbach in 1951, as he had intended to continue with further coefficients. The measure can be viewed as an extension of the Kuder–Richardson Formula 20 (KR-20), which is an equivalent measure for dichotomous items. Alpha is not robust against missing data. Several other Greek letters have been used by later researchers to designate other measures used in a similar context.[3] Somewhat related is the average variance extracted (AVE).

This article discusses the use of  in psychology, but Cronbach's alpha statistic is widely used in the social sciences, business, nursing, and other disciplines. The term item is used throughout this article, but items could be anything—questions, raters, indicators—of which one might ask to what extent they "measure the same thing." Items that are manipulated are commonly referred to as variables.

in psychology, but Cronbach's alpha statistic is widely used in the social sciences, business, nursing, and other disciplines. The term item is used throughout this article, but items could be anything—questions, raters, indicators—of which one might ask to what extent they "measure the same thing." Items that are manipulated are commonly referred to as variables.

Definition

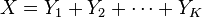

Suppose that we measure a quantity which is a sum of  components (K-items or testlets):

components (K-items or testlets):

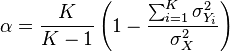

. Cronbach's

. Cronbach's  is defined as

is defined as

where  is the variance of the observed total test scores, and

is the variance of the observed total test scores, and  the variance of component i for the current sample of persons.[4]

the variance of component i for the current sample of persons.[4]

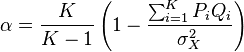

If the items are scored 0 and 1, a shortcut formula is[5]

where  is the proportion scoring 1 on item i, and

is the proportion scoring 1 on item i, and  . This is the same as KR-20.

. This is the same as KR-20.

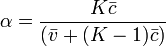

Alternatively, Cronbach's  can be defined as

can be defined as

where  is as above,

is as above,  the average variance of each component (item), and

the average variance of each component (item), and  the average of all covariances between the components across the current sample of persons (that is, without including the variances of each component).

the average of all covariances between the components across the current sample of persons (that is, without including the variances of each component).

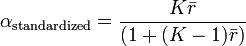

The standardized Cronbach's alpha can be defined as

where  is as above and

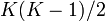

is as above and  the mean of the

the mean of the  non-redundant correlation coefficients (i.e., the mean of an upper triangular, or lower triangular, correlation matrix).

non-redundant correlation coefficients (i.e., the mean of an upper triangular, or lower triangular, correlation matrix).

Cronbach's  is related conceptually to the Spearman–Brown prediction formula. Both arise from the basic classical test theory result that the reliability of test scores can be expressed as the ratio of the true-score and total-score (error plus true score) variances:

is related conceptually to the Spearman–Brown prediction formula. Both arise from the basic classical test theory result that the reliability of test scores can be expressed as the ratio of the true-score and total-score (error plus true score) variances:

The theoretical value of alpha varies from zero to 1, since it is the ratio of two variances. However, depending on the estimation procedure used, estimates of alpha can take on any value less than or equal to 1, including negative values, although only positive values make sense.[6] Higher values of alpha are more desirable. Some professionals, as a rule of thumb, require a reliability of 0.70 or higher (obtained on a substantial sample) before they will use an instrument. Although Nunnally (1978) is often cited when it comes to this rule, he has actually never stated that 0.7 is a reasonable threshold in advanced research projects.[7] And obviously, this rule should be applied with caution when  has been computed from items that systematically violate its assumptions. Furthermore, the appropriate degree of reliability depends upon the use of the instrument. For example, an instrument designed to be used as part of a battery of tests may be intentionally designed to be as short as possible, and therefore somewhat less reliable. Other situations may require extremely precise measures with very high reliabilities. In the extreme case of a two-item test, the Spearman–Brown prediction formula is more appropriate than Cronbach's alpha.[8]

has been computed from items that systematically violate its assumptions. Furthermore, the appropriate degree of reliability depends upon the use of the instrument. For example, an instrument designed to be used as part of a battery of tests may be intentionally designed to be as short as possible, and therefore somewhat less reliable. Other situations may require extremely precise measures with very high reliabilities. In the extreme case of a two-item test, the Spearman–Brown prediction formula is more appropriate than Cronbach's alpha.[8]

This has resulted in a wide variance of test reliability. In the case of psychometric tests, most fall within the range of 0.75 to 0.83 with at least one claiming a Cronbach's alpha above 0.90 (Nunnally 1978, page 245–246).

Internal consistency

Cronbach's alpha will generally increase as the intercorrelations among test items increase, and is thus known as an internal consistency estimate of reliability of test scores. Because intercorrelations among test items are maximized when all items measure the same construct, Cronbach's alpha is widely believed to indirectly indicate the degree to which a set of items measures a single unidimensional latent construct. It is easy to show, however, that tests with the same test length and variance, but different underlying factorial structures can result in the same values of Cronbach's alpha. Indeed, several investigators have shown that alpha can take on quite high values even when the set of items measures several unrelated latent constructs.[1][9][10][11][12][13] As a result, alpha is most appropriately used when the items measure different substantive areas within a single construct. When the set of items measures more than one construct, coefficient omega_hierarchical is more appropriate.[14][15][16]

Alpha treats any covariance among items as true-score variance, even if items covary for spurious reasons. For example, alpha can be artificially inflated by making scales which consist of superficial changes to the wording within a set of items or by analyzing speeded tests.

A commonly accepted rule for describing internal consistency using Cronbach's alpha is as follows,[17][18][19] though a greater number of items in the test can artificially inflate the value of alpha[9] and a sample with a narrow range can deflate it, so this rule should be used with caution.

A commonly accepted rule of thumb for describing internal consistency is as follows:[17]

| Cronbach's alpha | Internal consistency |

|---|---|

| α ≥ 0.9 | Excellent |

| 0.9 > α ≥ 0.8 | Good |

| 0.8 > α ≥ 0.7 | Acceptable |

| 0.7 > α ≥ 0.6 | Questionable |

| 0.6 > α ≥ 0.5 | Poor |

| 0.5 > α | Unacceptable |

Generalizability theory

Cronbach and others generalized some basic assumptions of classical test theory in their generalizability theory. If this theory is applied to test construction, then it is assumed that the items that constitute the test are a random sample from a larger universe of items. The expected score of a person in the universe is called the universe score, analogous to a true score. The generalizability is defined analogously as the variance of the universe scores divided by the variance of the observable scores, analogous to the concept of reliability in classical test theory. In this theory, Cronbach's alpha is an unbiased estimate of the generalizability. For this to be true the assumptions of essential  -equivalence or parallelness are not needed. Consequently, Cronbach's alpha can be viewed as a measure of how well the sum score on the selected items capture the expected score in the entire domain, even if that domain is heterogeneous.

-equivalence or parallelness are not needed. Consequently, Cronbach's alpha can be viewed as a measure of how well the sum score on the selected items capture the expected score in the entire domain, even if that domain is heterogeneous.

Intraclass correlation

Cronbach's alpha is said to be equal to the stepped-up consistency version of the intraclass correlation coefficient, which is commonly used in observational studies. But this is only conditionally true. In terms of variance components, this condition is, for item sampling: if and only if the value of the item (rater, in the case of rating) variance component equals zero. If this variance component is negative, alpha will underestimate the stepped-up intra-class correlation coefficient; if this variance component is positive, alpha will overestimate this stepped-up intra-class correlation coefficient.

Factor analysis

Cronbach's alpha also has a theoretical relation with factor analysis. As shown by Zinbarg, Revelle, Yovel and Li,[15] alpha may be expressed as a function of the parameters of the hierarchical factor analysis model which allows for a general factor that is common to all of the items of a measure in addition to group factors that are common to some but not all of the items of a measure. Alpha may be seen to be quite complexly determined from this perspective. That is, alpha is sensitive not only to general factor saturation in a scale but also to group factor saturation and even to variance in the scale scores arising from variability in the factor loadings. Coefficient omega_hierarchical[14][15] has a much more straightforward interpretation as the proportion of observed variance in the scale scores that is due to the general factor common to all of the items comprising the scale.

Notes

- 1 2 Cronbach LJ (1951). "Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests". Psychometrika 16 (3): 297–334. doi:10.1007/bf02310555.

- ↑ Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Assessment of Reliability. In: Psychometric Theory (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- ↑ Revelle W Zinbarg R (2009). "Coefficients Alpha, Beta, Omega, and the glb: Comments on Sijtsma". Psychometrika 74 (1): 145–154. doi:10.1007/s11336-008-9102-z.

- ↑ Develles RF (1991). Scale Development. Sage Publications. pp. 24–33.

- ↑ Cronbach LJ (1970). Essentials of Psychological Testing. Harper & Row. p. 161.

- ↑ Ritter, N. (2010). "Understanding a widely misunderstood statistic: Cronbach's alpha". Paper presented at Southwestern Educational Research Association (SERA) Conference 2010: New Orleans, LA (ED526237).

- ↑ Nunnally JC (1978). Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- ↑ Eisinga, R.; Te Grotenhuis, M.; Pelzer, B. (2013). "The reliability of a two-item scale: Pearson, Cronbach or Spearman-Brown?". International Journal of Public Health 58 (4): 637–642. doi:10.1007/s00038-012-0416-3.

- 1 2 Cortina, J.M. (1993). "What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications". Journal of Applied Psychology 78: 98–104. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.78.1.98.

- ↑ Green SB Lissitz RW Mulaik SA (1977). "Limitations of coefficient alpha as an index of test unidimensionality". Educational and Psychological Measurement 37: 827–838. doi:10.1177/001316447703700403.

- ↑ Revelle W (1979). "Hierarchical cluster analysis and the internal structure of tests". Multivariate Behavioral Research 14: 57–74. doi:10.1207/s15327906mbr1401_4.

- ↑ Schmitt N (1996). "Uses and abuses of coefficient alpha". Psychological Assessment 8: 350–353. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.8.4.350.

- ↑ Zinbarg R Yovel I Revelle W McDonald R (2006). "Estimating generalizability to a universe of indicators that all have an attribute in common: A comparison of estimators for alpha". Applied Psychological Measurement 30: 121–144. doi:10.1177/0146621605278814.

- 1 2 McDonald RP (1999). Test Theory: A Unified Treatment. Erlbaum. pp. 90–103. ISBN 0805830758.

- 1 2 3 Zinbarg R Revelle W Yovel I Li W (2005). "Cronbach’s , Revelle’s , and McDonald’s : Their relations with each other and two alternative conceptualizations of reliability". Psychometrika 70: 123–133. doi:10.1007/s11336-003-0974-7.

- ↑ Dunn, T. J., Baguley, T. and Brunsden, V. (2013), From alpha to omega: A practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. British Journal of Psychology. doi:10.1111/bjop.12046

- 1 2 George, D., & Mallery, P. (2003). SPSS for Windows step by step: A simple guide and reference. 11.0 update (4th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

- ↑ Kline, P. (2000). The handbook of psychological testing (2nd ed.). London: Routledge, page 13

- ↑ DeVellis, R.F. (2012). Scale development: Theory and applications. Los Angeles: Sage. pp. 109–110.

Further reading

- Allen, M.J., & Yen, W. M. (2002). Introduction to Measurement Theory. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press.

- Bland, J.M.; Altman, D.G. (1997). "Statistics notes: Cronbach's alpha". BMJ 314 (7080): 572. doi:10.1136/bmj.314.7080.572.

- Bonett, D.G. (2002). "Sample size requirements for testing and estimating coefficient alpha". Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics 27: 335–340. doi:10.3102/10769986027004335.

- Bonett, D.G. (2003). "Sample size requirements for comparing two alpha reliability coefficients". Applied Psychological Measurement 27: 72–74. doi:10.1177/0146621602239477.

- Bonett, D.G. (2010). "Varying coefficient meta-analytic methods for alpha reliability". Psychological Methods 15: 368–385. doi:10.1037/a0020142. PMID 20853952.

- Cronbach, Lee J.; Shavelson, Richard J. (2004). "My Current Thoughts on Coefficient Alpha and Successor Procedures". Educational and Psychological Measurement 64 (3): 391–418. doi:10.1177/0013164404266386.

External links

- The free web interface and R package cocron allows to statistically compare two or more dependent or independent cronbach alpha coefficients.