Criticism of the United States government

Criticism of the United States government and foreign policy encompasses a wide range of sentiments about the actions and policies of the United States.

Mentality, intentions and perceptions of American foreign policy

American exceptionalism

There is a sense in which America sometimes sees itself as qualitatively different from other nations and therefore cannot be judged by the same standards as other countries; this belief is sometimes termed American exceptionalism and can be traced to the so-called Manifest destiny. A writer in Time Magazine in 1971 described American exceptionalism as "an almost mystical sense that America had a mission to spread freedom and democracy everywhere."[1] American exceptionalism has widespread implications and transcribes into disregard to the international norms, rules and laws in U.S. foreign policy. For example, the U.S. refused to ratify a number of important international treaties such as Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, and American Convention on Human Rights; did not join the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention; and routinely conducts drone attacks and cruise missile strikes around the globe. American exceptionalism is sometimes linked with hypocrisy; for example, the U.S. keeps a huge stockpile of nuclear weapons while urging other nations not to get them, and justifies that it can make an exception to a policy of non-proliferation.[2]

Critics of American exceptionalism drew parallels with such historic doctrines as civilizing mission and white man's burden which were employed by Great Powers to justify their colonial conquests.[3]:267–268 When the United States didn't support an environmental treaty made by many nations in Kyoto or treaties made concerning the Geneva Convention, then many observers deemed American exceptionalism as counterproductive.[4]

Allegations of imperialism

There is a growing consensus among American historians and political scientists that the United States during the American Century grew into an empire resembling in many ways Ancient Rome.[5] Currently, there is a debate over implications of imperial tendencies of U.S. foreign policy on democracy and social order.[6][7]

In 2002, conservative political commentator Charles Krauthammer declared cultural, economical, technological and military superiority of the U.S. in the world a given fact. In his opinion, people were "coming out of the closet on the word empire".[8] More prominently, the New York Times Sunday magazine cover for January 5, 2003 featured a slogan "American Empire: Get Used To It." Inside, a Canadian author Michael Ignatieff characterized the American imperial power as an empire lite.[9] According to Newsweek reporter Fareed Zakaria, the Washington establishment has "gotten comfortable with the exercise of American hegemony and treats compromise as treason and negotiations as appeasement", and added, "This is not foreign policy; it's imperial policy."[10] Emily Eakin reflecting the intellectual trends of the time, summarized in the New York Times that, "America is no mere superpower or hegemon but a full-blown empire in the Roman and British sense. That, at any rate, is the consensus of some of the nation's most notable commentators and scholars."[8]

Many allies of the U.S. were critical of a new, unilateral sensibility tone in its foreign policy, and showed displeasure by voting, for example, against the U.S. in the United Nations in 2001.[11]

Financial interests and foreign policy

Some historians, including Andrew Bacevich, suggest that U.S. foreign policy is directed by "wealthy individuals and institutions."[12] In 1893, a decision to back a plot to overthrow the president Harrison in Hawaii was clearly motivated by business interests; it was an effort to prevent a proposed tariff increase on sugar. As a result, Hawaii became a U.S. state afterward.[13] There was allegation that the Spanish–American War in 1898 was motivated mainly by business interests in Cuba.[13]

During the first half of the 20th century the United States became engaged in a series of local conflicts in Latin America, which went into history as banana wars. The main purpose of these wars were to defend American commercial interests in the region. Later, U.S. Marine Corps Major General Smedley Butler famously wrote, "I spent 33 years and four months in active military service and during that period I spent most of my time as a high class muscle man for Big Business, for Wall Street and the bankers. In short, I was a racketeer, a gangster for capitalism."[14]

Some critics assert the U.S. decision to support the separatists in Colombia in 1903 was motivated largely by business interests centered on Panama Canal despite declarations that it aimed to "spread democracy" and "end oppression."[13] One can say that U.S. foreign policy does reflect the will of the people, however people might have a consumerist mentality, which justifies wars in their minds.[15]

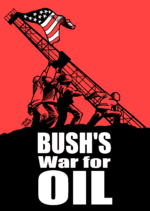

There are allegations that decisions to go to war in Iraq were motivated at least partially by oil interests; for example, a British newspaper The Independent reported that the "Bush administration is heavily involved in writing Iraq's oil law" which would "allow Western oil companies contracts to pump oil out of Iraq up to 30 years, and the profits would be tax-free."[13][16] Whether motivated by oil or not, U.S. foreign policy appears to much of the world as to have been motivated by oil rationale.[17]

Manipulation of U.S. foreign policy

Some political scientists maintained that setting economic interdependence as a foreign policy goal may have exposed the United States to manipulation. As a result, the U.S. trading partners gained an ability to influence the U.S. foreign policy decision-making process by manipulating, for example, the currency exchange rate, or restricting the flow of goods and raw materials. In addition, more than 40% of the U.S. foreign debt is currently owned by the big institutional investors from overseas, who continue to accumulate the Treasury bonds .[18]:9–10 A Washington Post reporter wrote that "several less-than-democratic African leaders have skillfully played the anti-terrorism card to earn a relationship with the United States that has helped keep them in power", and suggested, in effect, that therefore foreign dictators could manipulate U.S. foreign policy for their own benefit.[19] It is also possible for foreign governments to channel money through PACs to buy influence in Congress.

Lack of vision

The short-term election cycle coupled with the inability to stay focused on long term objectives motivates American presidents to lean towards actions that would appease the citizenry, and, as a rule, avoid complicated international issues and difficult choices. Thus, Brzezinski criticized the Clinton presidency as having a foreign policy which lacked "discipline and passion" and subjected the U.S. to "eight years of drift."[20] In comparison, the next, Bush presidency was criticized for many impulsive decisions that harmed the international standing of the U.S. in the world.[21] Former director of operations for the Joint Chiefs of Staff Lt. Gen. Gregory S. Newbold commented that, "There's a broad naivete in the political class about America's obligations in foreign policy issues, and scary simplicity about the effects that employing American military power can achieve".[22]

Allegations of arrogance

Some commentators have thought the United States became arrogant, particularly after its victory in World War II.[1] Critics such as Andrew Bacevich call on America to have a foreign policy "rooted in humility and realism."[16] Foreign policy experts such as Zbigniew Brzezinski counsel a policy of self-restraint and not pressing every advantage, and listening to other nations.[20] A government official called the U.S. policy in Iraq "arrogant and stupid," according to one report.[23]

Allegations of hypocrisy

The U.S. has been criticized for making statements supporting peace and respecting national sovereignty, but while carrying out military actions such as in Grenada, fomenting a civil war in Colombia to break off Panama, and Iraq. The U.S. has been criticized for advocating free trade but while protecting local industries with import tariffs on foreign goods such as lumber[25] and agricultural products. The U.S. has also been criticized for advocating concern for human rights while refusing to ratify the Convention on the Rights of the Child. The U.S. has publicly stated that it is opposed to torture, but has been criticized for condoning it in the School of the Americas. The U.S. has advocated a respect for national sovereignty but has supported internal guerrilla movements and paramilitary organizations, such as the Contras in Nicaragua.[26][27] The U.S. has been criticized for voicing concern about narcotics production in countries such as Bolivia and Venezuela but doesn't follow through on cutting certain bilateral aid programs.[28] The U.S. has been criticized for not maintaining a consistent policy; it has been accused of denouncing alleged rights violations in China while supporting alleged human rights abuses by Israel.[11]

However, some defenders argue that a policy of rhetoric while doing things counter to the rhetoric was necessary in the sense of realpolitik and helped secure victory against the dangers of tyranny and totalitarianism.[29]

The U.S. is advocating that Iran and North Korea should not develop nuclear weapons, while the US, the only country to have used nuclear weapons in warfare, maintains a nuclear arsenal of 5,113 warheads. However, this double-standard is legitimated by the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), to which Iran is a party.

Actions of the United States

Support of dictatorships

The U.S. has been criticized for supporting dictatorships with economic assistance and military hardware. Particular dictatorships have included Musharraf of Pakistan,[31] the Shah of Iran,[31] Museveni of Uganda,[19] warlords in Somalia,[19] Fulgencio Batista of Cuba, Ferdinand Marcos of the Philippines, Ngo Dinh Diem of South Vietnam, Park Chung-hee of South Korea, Generalissimo Franco of Spain, Melez Zenawi of Ethiopia, Augusto Pinochet in Chile,[32] Alfredo Stroessner of Paraguay,[33] Efraín Ríos Montt of Guatemala,[34] Jorge Rafael Videla of Argentina,[35] Suharto of Indonesia,[36][37] and Georgios Papadopoulos of Greece.

Opposition to independent nationalism

The U.S. has been criticized by Noam Chomsky for opposing nationalist movements in foreign countries, including social reform.[38][39]

Interference in internal affairs

The United States was criticized for manipulating the internal affairs of foreign nations, including Guatemala,[31] Chile,[31] Cuba,[13] Colombia,[13] various countries in Africa[19] including Uganda.[19]

Promotion of democracy

Some critics argue that America's policy of advocating democracy may be ineffective and even counterproductive.[40][41] Zbigniew Brzezinski declared that "[t]he coming to power of Hamas is a very good example of excessive pressure for democratization" and argued that George W. Bush's attempts to use democracy as an instrument against terrorism were risky and dangerous.[42][42][42] Analyst Jessica Tuchman Mathews of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace agreed that imposing democracy "from scratch" was unwise, and didn't work.[17] Realist critics such as George F. Kennan argued U.S. responsibility is only to protect its own citizens and that Washington should deal with other governments on that basis alone; they criticize president Woodrow Wilson's emphasis on democratization and nation-building although it wasn't mentioned in Wilson's Fourteen Points,[43] and the failure of the League of Nations to enforce international will regarding Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, and Imperial Japan in the 1930s. Realist critics attacked the idealism of Wilson as being ill-suited for weak states created at the Paris Peace Conference. Others, however, criticize the U.S. Senate's decision not to join the League of Nations which was based on isolationist public sentiment as being one cause for the organization's ineffectiveness.

Human rights problems

President Bush has been criticized for neglecting democracy and human rights by focusing exclusively on an effort to fight terrorism.[19][19] The U.S. was criticized for alleged prisoner abuse at Guantánamo Bay, Abu Ghraib in Iraq, and secret CIA prisons in eastern Europe, according to Amnesty International.[44] In response, the U.S. government claimed incidents of abuse were isolated incidents which did not reflect U.S. policy.

Militarism

In the 1960s, Martin Luther King Jr. criticized excessive U.S. spending on military projects,[45] and suggested a linkage between its foreign policy abroad and racism at home.[45] In 1971, a Time Magazine essayist wondered why there were 375 major foreign military bases around the world with 3,000 lesser military facilities and concluded "there is no question that the U.S. today has too many troops scattered about in too many places."[1] In a 2010 defense report, Cordesman criticized out-of-control military spending.[46] Expenditures to fight the War on Terror are vast and seem limitless.[47] The Iraq war was expensive and continues to be a severe drain on U.S. finances.[17][17] Bacevich thinks the U.S. has a tendency to resort to military means to try to solve diplomatic problems.[15] The U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War was a costly, decade-long military engagement which ended in defeat, and the mainstream view today is that the entire intervention was a mistake. The dollar cost was $111 billion, or $698 billion in 2009 dollars.[48] Similarly, the second Iraq war was viewed by many as being a mistake, since there were no weapons of mass destruction found, the war ended in December 2011.

Violation of international law

The U.S. doesn't always follow international law. For example, some critics assert the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq was not a proper response to an imminent threat, but an act of aggression which violated international law.[49][50] For example, Benjamin Ferencz, a chief prosecutor of Nazi war crimes at Nuremberg said George W. Bush should be tried for war crimes along with Saddam Hussein for starting aggressive wars—Saddam for his 1990 attack on Kuwait and Bush for his 2003 invasion of Iraq.[51] Critics point out that the United Nations Charter, ratified by the U.S., prohibits members from using force against fellow members except against imminent attack or pursuant to an explicit Security Council authorization.[52] A professor of international law asserted there was no authorization from the UN Security Council which made the invasion "a crime against the peace."[52] However, U.S. defenders argue there was such an authorization according to UN Security Council Resolution 1441. See also, United States War Crimes. The U.S. has also supported Kosovo's independence even though it is strictly written in UN Security Council Resolution 1244 that Kosovo cannot be independent and it is stated as a Serbian province. The U.S. has actively supported and pressured other countries to recognize Kosovo's independence.

Commitment to foreign aid

Some critics charge that U.S. government aid should be higher given the high levels of gross domestic product. They claim other countries give more money on a per capita basis, including both government and charitable contributions. By one index which ranked charitable giving as a percentage of GDP, the U.S. ranked 21 of 22 OECD countries by giving 0.17% of GDP to overseas aid, and compared the U.S. to Sweden which gave 1.03% of its GDP, according to different estimates.[53][54] The U.S. pledged 0.7% of GDP at a global conference in Mexico.[55] According to one estimate, U.S. overseas aid fell 16% from 2005 to 2006.[56] However, since the U.S. grants tax breaks to nonprofits, it subsidizes relief efforts abroad,[57] although other nations also subsidize charitable activity abroad.[58] Most foreign aid (79%) came not from government sources but from private foundations, corporations, voluntary organizations, universities, religious organizations and individuals. According to the Index of Global Philanthropy, the United States is the top donor in absolute amounts.[59]

- Environmental policy. The U.S. has been criticized for failure to support the 1997 Kyoto Protocol.[4][60]

Historical foreign policy

The U.S. has been criticized for its historical treatment of Native Americans. For example, the treatment of Cherokee Indians in the Trail of Tears in which hundreds of Indians died in a forced evacuation from their homes in the southeastern area, along with massacres, displacement of lands, swindles, and breaking treaties. It has been criticized for the war with Mexico in the 1840s which some see as a theft of land. It has been criticised for being the first and only nation to use a nuclear bomb in wartime.

The Holocaust

There has been sharp criticism about the U.S. response to the Holocaust: That it failed to admit Jews fleeing persecution from Europe at the beginning of World War II, and that it did not act decisively enough to prevent or stop the Holocaust. Franklin D. Roosevelt, who was the President at the time, was well-informed about the Hitler regime and its anti-Jewish policies,[61] but the U.S. State Department policies made it very difficult for Jewish refugees to obtain entry visas. Roosevelt similarly took no action on the Wagner-Rogers Bill, which could have saved 20,000 Jewish refugee children, following the arrival of 936 Jewish refugees on the MS St. Louis, who were denied asylum and were not allowed into the United States because of strict laws passed by Congress.[62]

During the era, the American press did not always publicize reports of Nazi atrocities in full or with prominent placement.[63] By 1942, after newspapers began to report details of the Holocaust, articles were extremely short and were buried deep in the newspaper. These reports were either denied or unconfirmed by the United States government. When it did receive irrefutable evidence that the reports were true, (and photographs of mass graves and murder in Birkenau camp in 1943, with victims moving into the gas chambers) U.S. officials suppressed the information and classified it as secret.[64] It is possible lives of European Jews could have been saved.

Alienation of allies

There is evidence that many U.S. allies have been alienated by a unilateral approach. Allies signaled dissatisfaction with U.S. policy in a vote at the U.N.[11] Brzezinski counsels listening to allies and exercising self-restraint.[20]

Ineffective public relations

One report suggests that news source Al-jazeera routinely paints the U.S. as evil throughout the Mideast.[23] Other critics have faulted the U.S. public relations effort.[4][19] As a result of faulty policy and lackluster public relations, the U.S. has a severe image problem in the Mideast, according to Anthony Cordesman.[65] Analyst Jessica Tuchman Mathews writes that it appears to much of the Arab world that the United States went to war in Iraq for oil, regardless of the accuracy of that motive.[17] In a 2007 poll by BBC News asking which countries are seen as having a "negative influence in the world," the survey found that Israel, Iran, United States and North Korea had the most negative influence, while nations such as Canada, Japan and the European Union had the most positive influence.[66] The U.S. has been accused by some U.N. officials of condoning actions by Israel against Palestinians.[11] On the other hand, others have accused the U.S. of being too supportive of the Palestinians.[67][68]

Ineffective prosecution of war

One estimate is that the second Iraq War along with the so-called War on Terror cost $551 billion, or $597 billion in 2009 dollars.[69] Boston University professor Andrew Bacevich has criticized American profligacy[16] and squandering its wealth.[15] There have been historical criticisms of U.S. warmaking capability; in the War of 1812, the U.S. was unable to conquer Canada despite several attempts and having superior resources;[1] the U.S. Capitol was burned and the settlement ending the war did not bring any major concessions from the British.[70]

Problem areas festering

Critics point to a list of countries or regions where continuing foreign policy problems continue to present problems. These areas include South America,[71] including Ecuador,[72] Venezuela,[71] Bolivia, Uruguay, and Brazil. There are difficulties with Central American nations such as Honduras.[73][73][73] Iraq has continuing troubles.[74] Iran, as well, presents problems with nuclear proliferation.[75] Pakistan is unstable,[74] there is active conflict in Afghanistan.[76] The Middle East in general continues to fester,[17] although relations with India are improving.[77] Policy towards Russia remains uncertain.[78] China presents an economic challenge.[17][79] There are difficulties in other regions too. In addition, there are problems not confined to particular regions, but regarding new technologies. Cyberspace is a constantly changing technological area with foreign policy repercussions.[80] Climate change is an unresolved foreign policy issue, particularly depending on whether nations can agree to work together to limit possible future risks.[17]

Ineffective strategy to fight terrorism

Critic Cordesman criticized U.S. strategy to combat terrorism as not having enough emphasis on getting Islamic republics to fight terrorism themselves.[81] Sometimes visitors have been misidentified as "terrorists."[82] Mathews suggests the risk of nuclear terrorism remains unprevented.[17] In 1999 during the Kosovo War, the U.S. supported the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA), a that was recognised as a terrorist organisation by the U.S. some years prior. Right before the 1999 bombing of Yugoslavia took place, the U.S. took down the KLA from the list of internationally recognized terrorist organizations in order to justify their aid and help to the KLA.

Historical instances of ineffective policies

Generally during the 19th century, and in early parts of the 20th century, the U.S. pursued a policy of isolationism and generally avoided entanglements with European powers. After World War I, Time Magazine writer John L. Steele thought the U.S. tried to return to an isolationist stance, but that this was unproductive. He wrote: "The anti-internationalist movement reached a peak of influence in the years just before World War II."[1] But Steele questioned whether this policy was effective; regardless, isolationism ended quickly after the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941.[1] Analysts have wondered whether the U.S. pursued the correct strategy with Japan before World War II; by denying Japan access to precious raw materials, it is possible that U.S. policy triggered the surprise attack and, as a result, the U.S. had to fight a two-front war in both the Far East as well as Europe during World War II. While it may be the case that the Mideast is a difficult region with no easy solutions to avoiding conflict, since this volatile region is at the junction of three continents; still, many analysts think U.S. policy could have been improved substantially. The U.S. waffled; there was no vision; presidents kept changing policy. Public opinion in different regions of the world thinks that, to some extent, the 9/11 attacks were an outgrowth of substandard U.S. policy towards the region.[83] The Vietnam War was a decade-long mistake.[1] The U.S. supported the secession of Kosovo form FR Yugoslavia in 1999 and continued to support its independence since. Such unilateral policies have broken European and international treaties but have been dismissed as unique by the US. Such unilateral secession support has helped inspire many notable secessionist uprisings in Spain, Belgium, Georgia, Russia, China, among others that have secessionist movements. However, the U.S. has dismissed any similarities between those secessionist movements and Kosovo.

Spying and surveillance

Role of internal government structure

Small role of Congress in foreign policy

Critic Robert McMahon thinks Congress has been excluded from foreign policy decision making, and that this is detrimental.[84] Other writers suggest a need for greater Congressional participation.[17]

Jim Webb, former Democratic senator from Virginia and former Secretary of the Navy in the Reagan administration, believes that Congress has an ever-decreasing role in U.S. foreign policy making. September 11, 2001 precipitated this change, where "powers quickly shifted quickly to the Presidency as the call went up for centralized decision making in a traumatized nation where, quick, decisive action was considered necessary. It was considered politically dangerous and even unpatriotic to question this shift, lest one be accused of impeding national safety during a time of war."[85] Since that time, Webb thinks Congress has become largely irrelevant in shaping and executing of U.S. foreign policy. He cites the Strategic Framework Agreement (SFA), the U.S.-Afghanistan Strategic Partnership Agreement, and the 2011 military intervention in Libya as examples of growing legislative irrelevance. Regarding the SFA, "Congress was not consulted in any meaningful way. Once the document was finalized, Congress was not given the opportunity to debate the merits of the agreement, which was specifically designed to shape the structure of our long-term relations in Iraq" (11). "Congress did not debate or vote on this agreement, which set U.S. policy toward an unstable regime in an unstable region of the world."[85] The Iraqi Parliament, by contrast, voted on the measure twice. The U.S.-Afghanistan Strategic Partnership Agreement is described by the Obama Administration has a "legally binding executive agreement" that outlines the future of U.S.-Afghan relations and designated Afghanistan a major non-NATO ally. "It is difficult to understand how any international agreement negotiated, signed, and authored only by our executive branch of government can be construed as legally binding in our constitutional system," Webb argues.[85] Finally, Webb identifies the U.S. intervention in Libya as a troubling historical precedent. "The issue in play in Libya was not simply whether the president should ask Congress for a declaration of war. Nor was it wholly about whether Obama violated the edicts of the War Powers Act, which in this writer's view he clearly did. The issue that remains to be resolved is whether a president can unilaterally begin, and continue, a military campaign for reasons that he alone defines as meeting the demanding standards of a vital national interest worth of risking American lives and expending billions of dollars of taxpayer money."[85] When the military campaign lasted months, President Barack Obama did not seek approval of Congress to continue military activity.[85]

Presidential incompetency

The presidency of George W. Bush has been attacked by numerous critics from both parties as being particularly incompetent, short-sighted, unthinking, and partisan.[10] Bush's decision to launch the second Iraq War was criticized extensively;[16][20] writer John Le Carre criticized it as a "hare-brained adventure."[86] He was also criticized for advocating a policy of exporting democracy.[40][42][42] Brzezinski described Bush's foreign policy as "a historical failure."[20][20] Bush was criticized for being too secret regarding foreign policy and having a cabal subvert the proper foreign policy bureaucracy.[4] Other presidents, too, were criticized. The foreign policy of George H. W. Bush was lackluster, and while he was a "superb crisis manager," he "missed the opportunity to leave a lasting imprint on U.S. foreign policy because he was not a strategic visionary," according to Brzezinski.[20] He stopped the first Iraq War too soon without finishing the task of capturing Saddam Hussein.[87] Foreign policy expert Henry Kissinger criticized Jimmy Carter for numerous foreign policy mistakes including a decision to admit the ailing Shah of Iran into the United States for medical treatment, as well as a bungled military mission to try to rescue the hostages in Tehran.[88] Carter waffled from being "both too tough and too soft at the same time."[88]

Difficulty removing an incompetent president

Since the only way to remove an incompetent president is with the rather difficult policy of impeachment, it is possible for a marginally competent or incompetent president to stay in office for four to eight years and cause great mischief.[89][90] In recent years, there has been great attention to this issue given the presidency of George W. Bush, but there have been questions raised about the competency of Jimmy Carter in his handling of the Iran hostage crisis.

Presidents may lack experience

Since the constitution requires no prior experience in diplomacy, government, or military service, it is possible to elect presidents with scant foreign policy experience. Clearly the record of past presidents confirms this, and that presidents who have had extensive diplomatic, military, and foreign policy experience have been the exception, not the rule. In recent years, presidents had relatively more experience in such tasks as peanut farming, acting and governing governorships than in international affairs. It has been debated whether voters are sufficiently skillful to assess the foreign policy potential of presidential candidates, since foreign policy experience is only one of a long list of attributes in which voters tend to select candidates. The second Bush was criticized for inexperience in the Washington Post for being "not versed in international relations and not too much interested."[4]

Lack of control over foreign policy

During the early 19th century, general Andrew Jackson exceeded his authority on numerous times and attacked American Indian tribes as well as invaded the Spanish territory of Florida without official government permission. Jackson was not reprimanded or punished for exceeding his authority. Some accounts blame newspaper journalism called yellow journalism for whipping up virulent pro-war sentiment to help instigate the Spanish–American War. Some critics suggest foreign policy is manipulated by lobbies, such as the pro-Israel lobby[91] or the Arab one, although there is disagreement about the influence of such lobbies.[91] Nevertheless, Brzezinski wants stricter anti-lobbying laws.[20]

Excessive authority of the presidency

In contrast to criticisms that presidential attention is divided into competing tasks, some critics charge that presidents have too much power, and that there is the potential for tyranny or fascism. Some presidents circumvented the national security decision-making process.[4] Critics such as Dana D. Nelson of Vanderbilt in her book Bad for Democracy[92][93] and columnist David Sirota[94][95] and Texas law professor Sanford Levinson[96][97] see a danger in too much executive authority.

Over-burdened presidency

Presidents have not only foreign policy responsibilities, but sizeable domestic duties too. In addition, the presidency is the head of a political party. As a result, it is tough for one person to manage disparate tasks, in one view. Critics suggest Reagan was overburdened, which prevented him from doing a good job of oversight regarding the Iran–Contra affair. Brzezinski suggested in Foreign Affairs that President Barack Obama is similarly overburdened.[98] Some suggest a need for permanent non-partisan advisers.[1]

See also

- Criticism of the Iraq War

- American exceptionalism

- American Interventions in the Middle East

- American Empire

- Assassination attempts on Fidel Castro

- Bush Doctrine

- Carter Doctrine

- China Containment Policy

- Containment

- Contents of the United States diplomatic cables leak (United States)

- Covert U.S. regime change actions

- Détente

- Dollar hegemony

- Foreign Military Sales

- Foreign policy of the Barack Obama administration

- Foreign policy of the United States

- Human rights in the United States

- Human Rights Record of the United States

- Inverted totalitarianism

- Monroe Doctrine

- NATO

- Nixon Doctrine

- Powell Doctrine

- President of the United States

- Reagan Doctrine

- Roosevelt Corollary

- Truman Doctrine

- United States and state terrorism

- United States and the United Nations

- United States Agency for International Development

- United States, Chanceries of Foreign Governments

- United States Foreign Military Financing

- United States military aid

- Zbigniew Brzezinski

Criticism of United States government agencies

- Criticism of the Food and Drug Administration

- Criticism of the United States Patent and Trademark Office

- Criticism of the IRS

- Criticism of the Federal Aviation Administration

- Criticism of the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development

- Criticism of the Department of Homeland Security

- Criticism of the Drug Enforcement Administration

- Criticism of the Federal Emergency Management Agency

- Criticism of United States Border Patrol

Further reading

- Bacevich, Andrew J. The Limits of Power: The End of American Exceptionalism. New York: Metropolitan Books, 2008.

- Blum, William. America's Deadliest Export: Democracy : the Truth About US Foreign Policy and Everything Else. Halifax, N.S.: Fernwood Pub, 2013.

- Chomsky, Noam, and David Barsamian. Imperial Ambitions: Conversations on the Post-9/11 World. New York: Metropolitan Books, 2005.

- Cramer, Jane K., and A. Trevor Thrall. Why Did the United States Invade Iraq? Hoboken: Taylor & Francis, 2011.

- Davidson, Lawrence. Foreign Policy, Inc.: Privatizing America's National Interest. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2009.

- Eland, Ivan. The Empire Has No Clothes: U.S. Foreign Policy Exposed. Oakland, Calif: Independent Institute, 2004. ISBN 0-945999-98-4

- Esparza, Marcia; Henry R. Huttenbach; Daniel Feierstein, eds. State Violence and Genocide in Latin America: The Cold War Years (Critical Terrorism Studies). Routledge, 2011. ISBN 0415664578

- Foner, Philip Sheldon. The Spanish-Cuban-American War and the Birth of American Imperialism, 1895-1902. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1972.

- Gould, Carol. Don't Tread on Me: Anti-Americanism Abroad. New York: Encounter Books, 2009.

- Grandin, Greg. The Last Colonial Massacre: Latin America in the Cold War. University Of Chicago Press, 2011. ISBN 9780226306902

- Immerman, Richard H. Empire for Liberty: A History of American Imperialism from Benjamin Franklin to Paul Wolfowitz. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010.

- Lichtblau, Eric. The Nazis Next Door: How America Became a Safe Haven for Hitler's Men. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014. ISBN 0547669194

- Marsden, Lee. For God's Sake: The Christian Right and US Foreign Policy. London: Zed Books, 2008.

- Maier, Charles S. Among Empires: American Ascendancy and Its Predecessors. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006.

- Mearsheimer, John J., and Stephen M. Walt. The Israel Lobby and US Foreign Policy. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007.

- Zinn, Howard. A People's History of the United States: 1492-Present. New York: Harper Collins, 2003.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 John L. Steele (May 31, 1971). "Time Essay: HOW REAL IS NEO-ISOLATIONISM?". Time Magazine. Retrieved 2009-12-22.

- ↑ Glenn Kessler (June 8, 2007). "A Foreign Policy, In Two Words". Washington Post. Retrieved 2009-12-21.

- ↑ Chomsky, Noam. Failed States: The Abuse of Power and the Assault on Democracy. New York: Metropolitan Books/Henry Holt, 2006.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Dana Milbank (October 20, 2005). "Colonel Finally Saw Whites of Their Eyes". Washington Post. Retrieved 2009-12-21.

- ↑ Andrew J. Bacevich, American Empire: The Realities and Consequences of U.S. Diplomacy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002.

- ↑ Nexon, Daniel and Wright, Thomas. What's at Stake in the American Empire Debate. American Political Science Review, Vol. 101, No. 2 (May 2007), p. 266-267

- ↑ Andrew J. Bacevich. (Ed.) The Imperial Tense: Prospects and Problems of American Empire. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2003.

- 1 2 Eakin, Emily (March 31, 2002). "Ideas & Trends; All Roads Lead To D.C.". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ↑ Ignatieff, Michael (January 5, 2003). "The American Empire; The Burden". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- 1 2 Fareed Zakaria (March 14, 2009). "Why Washington Worries–Obama has made striking moves to fix U.S. foreign policy—and that has set off a chorus of criticism.". Newsweek. Retrieved 2009-12-18.

- 1 2 3 4 Tony Karon, Stewart Stogel (May 4, 2001). "U.N. Defeat Was a Message from Washington's Allies". Time Magazine. Retrieved 2009-12-22.

- ↑ Andrew J. Bacevich (May 27, 2007). "I Lost My Son to a War I Oppose. We Were Both Doing Our Duty.". Washington Post. Retrieved 2009-12-21.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 DeWayne Wickham (January 16, 2007). "Dollars, not just democracy, often drive U.S. foreign policy". USA Today. Retrieved 2009-12-22.

- ↑ Butler, Smedley D. War Is a Racket: The Antiwar Classic by America's Most Decorated General, Two Other Anti-Interventionist Tracts, and Photographs from The Horror of It. Los Angeles, Calif: Feral House, 2003.

- 1 2 3 Alex Kingsbury (August 19, 2008). "How America Is Squandering Its Wealth and Power: Andrew Bacevich, a military veteran and scholar, blames the Bush administration and the American people.". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved 2009-12-21.

- 1 2 3 4 Amy Chua (October 22, 2009). "Where Is U.S. Foreign Policy Headed?". The New York Times: Sunday Book Review. Retrieved 2009-12-21.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Jessica Tuchman Mathews (October 10, 2007). "Six Years Later: Assessing Long-Term Threats, Risks and the U.S. Strategy for Security in a Post-9/11 World". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved 2009-12-22.

- ↑ Biddle, Stephen D. American Grand Strategy After 9/11: An Assessment. Carlisle, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, 2005.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Stephanie McCrummen (February 22, 2008). "U.S. Policy in Africa Faulted on Priorities: Security Is Stressed Over Democracy". Washington Post. Retrieved 2009-12-22.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 James M. Lindsay (book reviewer) (March 25, 2007). "The Superpower Blues: Zbigniew Brzezinski says we have one last shot at getting the post-9/11 world right. book review of "Second Chance" by Zbigniew Brzezinski". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2009-12-21.

- ↑ Bartlett, Bruce R. Impostor: How George W. Bush Bankrupted America and Betrayed the Reagan Legacy. New York: Doubleday, 2006.

- ↑ Londono, Ernesto (August 29, 2013). "U.S. military officers have deep doubts about impact, wisdom of a U.S. strike on Syria". Washington Post. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- 1 2 Scott MacLeod (October 29, 2006). "Tearing Down The Walls". Time Magazine. Retrieved 2009-12-21.

- ↑ Shaking Hands with Saddam Hussein: The U.S. Tilts toward Iraq, 1980-1984. National Security Archive, Electronic Briefing Book No. 82. Ed. by Joyce Battle, February 25, 2003.

- ↑ "Canada attacks U.S. on wood tariffs". BBC. 2005-10-25. Retrieved 24 March 2008.

- ↑ Satter, Raphael (2007-05-24). "Report hits U.S. on human rights". Associated Press (published on The Boston Globe). Retrieved 2007-05-29.

- ↑ "World Report 2002: United States". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 2007-06-02.

- ↑ "U.S. keeps Venezuela, Bolivia atop narcotics list". Reuters. September 16, 2009. Retrieved 2009-12-21.

- ↑ Bootie Cosgrove-Mather (February 1, 2005). "Democracy And Reality". CBS News. Retrieved 2009-12-21.

- ↑ Who Is the World's Worst Dictator?

- 1 2 3 4 Matthew Yglesias (2008-05-28). "Are Kissinger's Critics Anti-Semitic?". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2009-12-21.

- ↑ Peter Kornbluh (September 11, 2013). The Pinochet File: A Declassified Dossier on Atrocity and Accountability. The New Press. ISBN 1595589120 p. xviii

- ↑ Alex Henderson (February 4, 2015). 7 Fascist Regimes Enthusiastically Supported by America. Alternet. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ↑ What Guilt Does the U.S. Bear in Guatemala? The New York Times, May 19, 2013. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- ↑ Duncan Campbell (December 5, 2003). Kissinger approved Argentinian 'dirty war'. The Guardian. Retrieved August 29, 2015.

- ↑ David A. Blumenthal and Timothy L. H. McCormack (2007). The Legacy of Nuremberg: Civilising Influence or Institutionalised Vengeance? (International Humanitarian Law). Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 9004156917 pp. 80–81.

- ↑ Kai Thaler (December 2, 2015). 50 years ago today, American diplomats endorsed mass killings in Indonesia. Here's what that means for today. The Washington Post. Retrieved December 4, 2015.

- ↑ Chomsky, Noam (2006-03-28). "The Israel Lobby?". ZNet. Retrieved 2009-01-13.

- ↑ "Noam Chomsky on America's Foreign Policy". PBS. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- 1 2 Paul Magnusson (book reviewer) (2002-12-30). "Is Democracy Dangerous? Book review of: WORLD ON FIRE–How Exporting Free Market Democracy Breeds Ethnic Hatred and Global Instability; By Amy Chua". Business Week. Retrieved 2009-12-21.

- ↑ EMILY EAKIN (January 31, 2004). "On the Dark Side Of Democracy". The New York Times: Books. Retrieved 2009-12-21.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Roger Cohen (April 5, 2006). "Freedom May Rock Boat, but It Can't Be Selective". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-12-21.

- ↑

Fourteen Points Speech

Fourteen Points Speech - ↑ "Report 2005 USA Summary". Amnesty International. 2005. Retrieved 2009-12-24.

- 1 2 Patrick W. Gavin (January 16, 2004). "The Martin Luther King Jr. America has ignored". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 2009-12-22.

- ↑ Anthony H. Cordesman, Erin K. Fitzgerald (September 8, 2009). "The 2010 Quadrennial Defense Review". CSIS: Center for Strategic and International Studies. Retrieved 2009-12-22.

- ↑ Anthony H. Cordesman (August 9, 2007). "The Uncertain Cost of the Global War on Terror". CSIS: Center for Strategic and International Studies. Retrieved 2009-12-22.

- ↑ "Vietnam War". CNBC. 2009-12-27. Retrieved 2009-12-27.

- ↑ Stuart Taylor Jr. and Evan Thomas (April 18, 2009). "http://www.newsweek.com/id/194651". Newsweek. Retrieved 2009-12-27. External link in

|title=(help) - ↑ Principles of International Law Recognized in the Charter of the Nürnberg Tribunal and in the Judgment of the Tribunal, 1950. on the website of the United Nations

- ↑ "US and Foreign Aid Assistance". Global Issues. 2009. Retrieved 2009-12-24.

- ↑ "US and Foreign Aid Assistance". Global Issues. 2009. Retrieved 2009-12-24.

- ↑ "UN Millennium Project–Fast Facts". UNDP. 2005. Retrieved 2009-12-24.

- ↑ "UN Millennium Project–Fast Facts". OECD. 2007. Retrieved 2009-12-24.

- ↑ "Papers". ssrn. 2007. Retrieved 2009-12-24.

- ↑ "U.S. and Foreign Aid Assistance". Global Issues. 2007. Retrieved 2009-12-24.

- ↑ "Foreign aid". America.gov. 2007-05-24. Retrieved 2009-12-24.

- ↑ "Bush + Blair = Buddies". CBS News. July 19, 2001. Retrieved 2009-12-22.

- ↑ "FRANKLIN DELANO ROOSEVELT". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ↑ Joseph J. Plaud, Ph.D., BCBA. "Historical Perspectives on Franklin D. Roosevelt, American Foreign Policy, and the Holocaust". Franklin D. Roosevelt American Heritage Center and Museum. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ↑ "THE UNITED STATES AND THE HOLOCAUST". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ↑ "The Holocaust: World Response". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ↑ Anthony H. Cordesman (September 25, 2006). "Winning the War on Terrorism: The Need for a Fundamentally Different Strategy (see pdf file p.3)". CSIS: Center for Strategic and International Studies. Retrieved 2009-12-22.

- ↑ Nick Childs (2007-03-06). "Israel, Iran top 'negative list'". BBC News. Retrieved 2009-12-26.

- ↑ "Palestinians accost U.S. delegation in West Bank". The Guardian. 4 October 2011. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ↑ "U.S. Foreign Aid to the Palestinians" (PDF). Federation of American Scientists. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ↑ "Gulf War II / War on Terror". CNBC. 2009-12-27. Retrieved 2009-12-27.

- ↑ "Books: Mr. Madison's War". Time Magazine. November 3, 1961. Retrieved 2009-12-27.

- 1 2 Deborah Charles, Anthony Boadle (2009-12-21). "Clinton: U.S. worried by Venezuelan arms purchases". Reuters. Retrieved 2009-12-21.

- ↑ Alonso Soto (April 5, 2008). "Ecuador says CIA controls part of its intelligence". Reuters. Retrieved 2009-12-22.

- 1 2 3 Andres Oppenheimer (2009-12-06). "Latin America's honeymoon with Obama may be over". Miami Herald. Retrieved 2009-12-21.

- 1 2 David S. Broder (August 25, 2008). "A Candidate At Home In Scranton". Washington Post. Retrieved 2009-12-22.

- ↑ Anthony H. Cordesman, Adam Seitz (Jan 22, 2009). "Iranian Weapons of Mass Destruction". CSIS: Center for Strategic and International Studies. Retrieved 2009-12-22.

- ↑ Gilles Dorronsoro (2009-11-01). "Fixing a Failed Strategy in Afghanistan". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved 2009-12-22.

- ↑ Ashley J. Tellis (November 2009). "Manmohan Singh Visits Washington: Sustaining U.S.–Indian Cooperation Amid Differences". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved 2009-12-22.

- ↑ James Collins (March 12, 2009). "Opportunities for the U.S.-Russia Relationship". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved 2009-12-22.

- ↑ Albert Keidel (October 16, 2008). "China and the Global Financial Crisis". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved 2009-12-22.

- ↑ Christopher Boucek (December 16, 2009). "Understanding Cyberspace as a Medium for Radicalization and Counter-Radicalization". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved 2009-12-22.

- ↑ Anthony H. Cordesman (September 25, 2006). "Winning the War on Terrorism: The Need for a Fundamentally Different Strategy". CSIS: Center for Strategic and International Studies. Retrieved 2009-12-22.

- ↑ Scott Baldauf (November 16, 2007). "South African fights denial of U.S. visa–Adam Habib, a scholar and Iraq war critic, was denied a visa to the US for 'links to terrorism.'". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 2009-12-18.

- ↑ Joel Roberts (September 4, 2002). "Europe Polled On Why 9/11 Happened". CBS News. Retrieved 2009-12-21.

- ↑ Robert McMahon, Council on Foreign Relations (December 24, 2007). "The Impact of the 110th Congress on U.S. Foreign Policy". Washington Post. Retrieved 2009-12-21.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Webb, Jim (March–April 2013). "Congressional Abdication". The National Interest (124). Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- ↑ Raphael G. Satter, Associated Press (2008-09-15). "Report: John Le Carre says he nearly defected to Russia". USA Today. Retrieved 2009-12-22.

- ↑ James M. Lindsay (book reviewer) (March 25, 2007). "The Superpower Blues: Zbigniew Brzezinski says we have one last shot at getting the post-9/11 world right. book review of "Second Chance" by Zbigniew Brzezinski". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2009-12-21.

- 1 2 "Nation: Kissinger: What Next for the U.S.?". Time Magazine. May 12, 1980. Retrieved 2009-12-21.

- ↑ Sanford Levinson (September 17, 2008). "Constitution Day Essay 2008: Professor Sanford Levinson examines the dictatorial power of the Presidency". University of Texas School of Law.

- ↑ Sanford Levinson (LA Times article available on website) (October 16, 2006). "Our Broken Constitution". University of Texas School of Law -- News & Events. Retrieved 2009-10-10.

- 1 2 Patricia Cohen (August 16, 2007). "Backlash Over Book on Policy for Israel". The New York Times: Books. Retrieved 2009-12-18.

- ↑ Nelson, Dana D. (2008). Bad for Democracy: How the Presidency Undermines the Power of the People. Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-8166-5677-6.

- ↑ Sirota, David (August 22, 2008). "The Conquest of Presidentialism". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 2009-09-20.

- ↑ David Sirota (August 22, 2008). "Why cult of presidency is bad for democracy". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2009-09-20.

- ↑ David Sirota (January 18, 2009). "U.S. moving toward czarism, away from democracy". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2009-09-21.

- ↑ Sanford Levinson (February 5, 2009). ""Wartime Presidents and the Constitution: From Lincoln to Obama" -- speech by Sanford Levinson at Wayne Morse Center". Wayne Morse Center for Law and Politics. Retrieved 2009-10-10.

- ↑ Anand Giridharadas (September 25, 2009). "Edging Out Congress and the Public". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-10-10.

- ↑ Zbigniew Brzezinski (2001-10-20). "From Hope to Audacity: Appraising Obama's Foreign Policy (I)". Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||

.svg.png)