Autonomous Republic of Crimea

Coordinates: 45°18′N 34°24′E / 45.3°N 34.4°E

Autonomous Republic of Crimea

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Motto: "Процветание в единстве" (Russian) Protsvetaniye v yedinstve (transliteration) Prosperity in Unity |

||||||

| Anthem: "Нивы и горы твои волшебны, Родина" (Russian) Nivy i gory tvoi volshebny, Rodina (transliteration) Your fields and mountains are magical, Motherland |

||||||

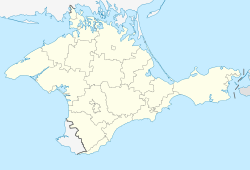

Location of the Autunomous Republic of Crimea (red) in Ukraine (light yellow) |

||||||

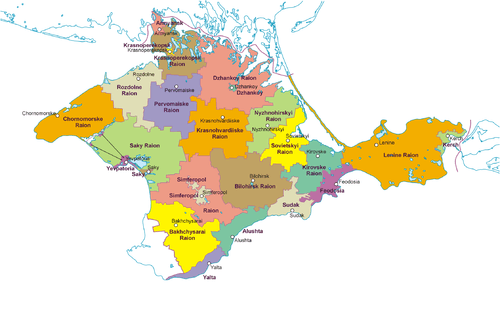

Location of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea (light yellow) in the Crimean Peninsula |

||||||

| Status | de jure | |||||

| Capital | Simferopola | |||||

| Official languages | Ukrainian | |||||

| Recognized regional languages | Russian, Crimean Tatarb | |||||

| Ethnic groups (2001) |

|

|||||

| Government | Autonomous republic | |||||

| • | Nataliya Popovych[1] | |||||

| Legislature | Supreme Council | |||||

| Establishment | ||||||

| • | Autonomy | 12 February 1991 | ||||

| • | Constitution | 21 October 1998 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| • | Total | 26,100 km2 (148th) 10,038 sq mi |

||||

| Population | ||||||

| • | 2001 census | 2,033,700 | ||||

| • | Density | 77.9/km2 (116th) 202.6/sq mi |

||||

| ISO 3166 code | UA-43 | |||||

| a. | Ukraine has not formed a government-in-exile for Crimea. On May 17, 2014, the Crimean Presidential Representative moved to Kherson, which is the only existing authority for the Autonomous Republic of Crimea.[2] | |||||

| b. | Because Ukrainian is the only state language in Ukraine, no other language may be official, although according to the Constitution of Crimea, Russian is the language of inter-ethnic communication. However, government duties are fulfilled mainly in Russian, hence it is a de facto official language. Crimean Tatar is also used. | |||||

|

||||||

The Autonomous Republic of Crimea (Ukrainian: Автономна Республіка Крим, Avtonomna Respublika Krym; Russian: Автономная Республика Крым, Avtonomnaya Respublika Krym; Crimean Tatar: Qırım Muhtar Cumhuriyeti)[3] was created on 12 February 1991 when the Crimean Oblast was upgraded to an autonomous republic within Ukraine following a referendum on 20 January 1991.[4]

In March 2014, following the takeover of the territory by pro-Russian separatists and Russian Armed Forces,[5] a controversial referendum was held on the issue of reunification with Russia; the official result was that a large majority wished to join with Russia.[6] Russia then annexed the whole of Crimea by signing a Treaty of Accession with the self-declared independent Republic of Crimea to incorporate the Republic of Crimea and the federal city of Sevastopol as federal subjects of Russia.[7]

While Russia and six other UN member states recognize Crimea as part of the Russian Federation, Ukraine continues to claim Crimea as an integral part of its territory, supported by most foreign governments and United Nations General Assembly Resolution 68/262.[8]

History

See also 1954 Transfer of Crimea

Background

The Crimean Khanate was established in the early 15th century and included all of the Crimean Peninsula except parts of the south and southwest coast that were controlled by the Republic of Genoa. In 1783, the whole of Crimea was annexed by the Russian Empire. The annexation began 171 years of Russian rule in Crimea, punctuated by short periods during political upheavals and wars, which ended with the transfer of the territory to the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, within the USSR.

Transfer to Ukraine

On 19 February 1954, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet issued a decree that transferred the Crimean Oblast from the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic to the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.[9][10] The reason for the transfer, as stated in the decree, was "the integral character of the economy, the territorial proximity and the close economic and cultural ties between the Crimea Province and the Ukrainian SSR.":[11]

Autonomous Republic within Ukraine

Following a referendum on 20 January 1991, the Crimean Oblast was upgraded to the status of an Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic on 12 February 1991 by the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR.

When the Soviet Union collapsed and Ukraine became an independent country, Crimea remained part of the newly independent Ukraine, leading to tensions between Russia and Ukraine[nb 1] with the Black Sea Fleet being based on the peninsula.

On 26 February 1992, the Crimean parliament renamed the ASSR the Republic of Crimea and proclaimed self-government on 5 May 1992[13][14] (which was yet to be approved by a referendum held 2 August 1992[15]) and passed the first Crimean constitution the same day.[15] On 6 May 1992 the same parliament inserted a new sentence into this constitution that declared that Crimea was part of Ukraine.[15]

On 19 May, Crimea agreed to remain part of Ukraine and annulled its proclamation of self-government but Crimean Communists forced the Ukrainian government to expand on the already extensive autonomous status of Crimea.[16]:587 In the same period, Russian president Boris Yeltsin and Ukrainian President Leonid Kravchuk agreed to divide the former Soviet Black Sea Fleet between Russia and the newly formed Ukrainian Navy.[17]

On 14 October 1993, the Crimean parliament established the post of President of Crimea and agreed on a quota of Crimean Tatars represented in the Council of 14. However, political turmoil continued. Amendments to the constitution eased the conflict, but on 17 March 1995, the parliament of Ukraine intervened by abolishing the Crimean Constitution of 1992, all the laws and decrees contradicting those of Kiev, among which were the laws guarantying representation for the Crimean Tartars and other ethnic groups, and removing Yuriy Meshkov (the President of Crimea) as well as the office of The President of Crimea.[18][19] After an interim constitution, the current constitution was put into effect, changing the territory's name to the Autonomous Republic of Crimea.

Following the ratification of the May 1997 Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation, and Partnership on friendship and division of the Black Sea Fleet, international tensions slowly eased. However, in 2006, anti-NATO protests broke out on the peninsula.[20] In September 2008, the Ukrainian Foreign Minister Volodymyr Ohryzko accused Russia of giving out Russian passports to the population in the Crimea and described it as a "real problem" given Russia's declared policy of military intervention abroad to protect Russian citizens.[21]

On 24 August 2009, anti-Ukrainian demonstrations were held in Crimea by ethnic Russian residents. Sergei Tsekov (of the Russian Bloc[22] and then deputy speaker of the Crimean parliament[23]) said then that he hoped that Russia would treat the Crimea the same way as it had treated South Ossetia and Abkhazia.[24] Chaos in the Ukrainian parliament erupted during a debate over the extension of the lease on a Russian naval base on 27 April 2010 after Ukraine's parliament ratified the treaty that extends Russia's lease on naval moorings and shore installations in port of Sevastopol and other locations in Crimea until 2042 with optional five-year renewals. Along with Verkhovna Rada, the treaty was ratified by the Russian State Duma as well.[25]

Events of 2014

On 26 February 2014, following the 2014 Ukrainian revolution, thousands of pro-Russian and pro-Ukraine protesters clashed in front of the parliament building in Simferopol. Reportedly, the reason for the clash on 23 February 2014 was the abolition of the law on languages of minorities, including Russian.[26] The decision, which would have made Ukrainian the sole state language, has not been upheld by interim Ukraine president Turchynov.[27][28]

The demonstrations followed the ousting of Ukraine President Viktor Yanukovych on 22 February 2014, and a push by pro-Russian protesters for Crimea to secede from Ukraine and seek assistance from Russia.[29]

On 28 February 2014, Russian forces occupied airports and other strategic locations in Crimea.[30] The interim Government of Ukraine described the events as an invasion and occupation of Crimea by Russian forces.[31][32] Gunmen, either armed militants or Russian special forces, occupied the Crimean parliament. Under armed guard and with the doors locked, members of parliament reportedly elected Sergey Aksyonov as the new Crimean Prime Minister. The de facto Crimean Prime Minister Sergey Aksyonov said that he asserted sole control over Crimea's security forces and appealed to Russia "for assistance in guaranteeing peace and calmness" on the peninsula. The central Ukrainian government did not recognize the Aksyonov administration and considers it illegal.[33][34] Ousted Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovich sent a letter to Putin asking him to use military force in Ukraine to restore law and order.[35] The Russian foreign ministry stated that "movement of the Black Sea Fleet armored vehicles in Crimea (...) happens in full accordance with basic Russian-Ukrainian agreements on the Black Sea Fleet".[36]

On 1 March, the Russian parliament granted President Vladimir Putin the authority to use military force in Ukraine.[37] The move was condemned by many Western and Western-aligned nations. On the same day, the acting president of Ukraine, Oleksandr Turchynov decried the appointment of the Prime Minister of Crimea as unconstitutional.[38] Russia established de facto control of the territory.

On 3 March, Ukrainian defense sources were reported to have said that the head of Russia's Black Sea Fleet gave Ukraine a deadline of dawn on the 4th to surrender their control of the Crimea, or face an assault by Russian troops occupying the area.[39] However, Interfax news agency later quoted a fleet spokesman who denied that any ultimatum had been issued.[39] Nothing came to pass at the deadline.

On 4 March, several Ukrainian bases and navy ships in Crimea reported being intimidated by Russian forces but vowed non-violence. Ukrainian warships were also effectively blockaded in their port of Sevastopol.[40][41]

On 6 March, members of the Crimean Parliament asked the Russian government for the region to become a subject of the Russian Federation with a referendum on the issue set for the Crimean region for March 16. The Ukrainian central government, the European Union, and the US all challenged the legitimacy of the request and of the following referendum. Article 73 of the Constitution of Ukraine states: "Alterations to the territory of Ukraine shall be resolved exclusively by an All-Ukrainian referendum."[42] International monitors arrived in Ukraine to assess the situation in Crimea but were halted by armed militants at the Crimean border.[43][44] Russian forces scuttled a Russian Kara-class Cruiser Ochakov across the entrance channel to Donuzlav Lake on the west coast of Crimea to blockade Ukrainian navy ships in their port.[45][46]

On 7 March, Russian forces scuttled a second ship, a diving support vessel, to further block the naval port at Donuzlav Lake.[46]

The Crimean parliament released the Ballot Questions for the 16 March referendum. The referendum questions were:

- "Do you support rejoining Crimea with Russia as a subject of the Russian Federation?"

- "Do you support restoration of the 1992 Constitution of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Crimea's status as a part of Ukraine?"

Only ballots with exactly one positive response were considered valid. There was no option on the 16 March ballot to maintain the status quo. Although some Ukrainian outlets considered the questions to be equivalent to "join Russia immediately" or "declare independence and then join Russia"[47][48] the Crimean constitution of 1992 would restore Republic of Crimea's autonomous status within the borders of Ukraine.[18][49] The current Crimean constitution, which came into effect in 1999 and Article 135 of the Ukrainian constitution, article 10 of which provides for the existence of an "Autonomous Republic of Crimea", provides that the Crimean Constitution must be approved by the Ukrainian parliament. Turnout for the referendum was 83%, and the overwhelming majority of those who voted (95.5%)[50] supported the option of rejoining Russia. However, a BBC reporter claimed that a "huge number of people in the minority population - the Tatars and Ukrainians - abstained from the vote", making it "difficult to tell if the figures added up".[51]

On 21 March 2014, the self-proclaimed Republic of Crimea signed a treaty of accession to the Russian Federation.[52] The accession was granted but separately for each the former regions that composed it: one accession for the Autonomous Republic of Crimea as the Republic of Crimea, and another accession for Sevastopol as a federal city.[53]

Politics and government

Under the Constitution of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, which is subject to the Constitution of Ukraine, the legislative body of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea is the Supreme Council of Crimea. Ukraine's national parliament voted to dissolve this 100-seat parliament in March 2014 as its leaders were finalising preparations for a referendum on whether to join Russia.[54] After the referendum, the members of the Supreme Council voted to rename themselves as the State Council of the Republic of Crimea, and also formally appealed to Russia to accept Crimea as part of the Russian Federation.[55]

According to the Constitution of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, executive power is exercised by the Council of Ministers of Crimea, headed by a Chairman, appointed and dismissed by the Supreme Council of Crimea, with the consent of the President of Ukraine.[56][57] The authority and operation of the Supreme Council and the Council of Ministers of Crimea are determined by the Constitution of Ukraine and other the laws of Ukraine, as well as by regular decisions of the Supreme Council of Crimea.[57]

There had been a post of President of Crimea from 1994 to 1995 but it was replaced by a Presidential Representative serving as Governor.

While not an official body controlling Crimea, the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People represents Crimean Tatars and could address grievances to the Ukrainian central government, the Crimean government, and international bodies.[58]

During the 2004 presidential elections and 2010 presidential elections, Crimea largely voted for the presidential candidate Viktor Yanukovych. In the 2006 Ukrainian parliamentary elections, the 2007 Ukrainian parliamentary elections and the 2012 Ukrainian parliamentary election, the Yanukovych-led Party of Regions also won most of the votes from the region, as they did in the 2006 Crimean parliamentary election and the 2010 Crimean parliamentary election.[59]

Administrative divisions

The Autonomous Republic of Crimea is subdivided into 25 administrative areas: 14 raions (districts) and 11 mis'kradas and mistos (city municipalities), officially known as territories governed by city councils.[60] While the City of Sevastopol is located on the Crimean peninsula, it is administratively separate from the Autonomous Republic of Crimea though tightly integrated within the infrastructure of the whole peninsula.

Raions

|

City municipalities |  |

The largest city is Simferopol with major centers of urban development including Kerch (heavy industry and fishing center), Dzhankoy (transportation hub), Yalta (holiday resort) and others.

-

Simferopol: capital

Simferopol: capital -

Kerch: Hero City, important industrial, transport and tourist center

Kerch: Hero City, important industrial, transport and tourist center -

Yevpatoria: major port, a rail hub, and resort city

Yevpatoria: major port, a rail hub, and resort city -

Feodosiya: port and resort city

Feodosiya: port and resort city -

Yalta: one of the most important resorts in Crimea

Yalta: one of the most important resorts in Crimea -

Dzhankoy: important railroad connection

Dzhankoy: important railroad connection -

Bakhchisaray: historical capital of the Crimean Khanate

Bakhchisaray: historical capital of the Crimean Khanate -

Krasnoperekopsk: industrial city

Krasnoperekopsk: industrial city -

Armyansk: industrial city

Armyansk: industrial city -

Alushta: resort city

Alushta: resort city

See also

Notes

References

- ↑ Турчинов назначил постпредом президента в Крыму Наталию Попович - Korrespondent.net (Russian)

- ↑ "Crimean Presidential Representative will be moved to Kherson". Ukrainian Independent Information Agency (in Russian). 17 May 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ↑ http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-o367786

- ↑ "Day in history - 20 January". RIA Novosti (in Russian). January 8, 2006. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved August 6, 2007.

- ↑ "Meeting of the Valdai International Discussion Club". Kremlin.ru. 2014-10-24. Archived from the original on 2015-04-15.

I will be frank; we used our Armed Forces to block Ukrainian units stationed in Crimea

- ↑ "Crimea applies to be part of Russian Federation after vote to leave Ukraine". The Guardian. 17 March 2014.

- ↑ Распоряжение Президента Российской Федерации от 17.03.2014 № 63-рп "О подписании Договора между Российской Федерацией и Республикой Крым о принятии в Российскую Федерацию Республики Крым и образовании в составе Российской Федерации новых субъектов" at the Wayback Machine (archived 18 March 2014) at http://www.pravo.gov.ru (Russian)

- ↑ "Kremlin: Crimea and Sevastopol are now part of Russia, not Ukraine". CNN. 18 March 2014.

- ↑ ""The Gift of Crimea".". www.macalester.edu. Retrieved 2014-03-06.

- ↑ ""Подарунок Хрущова". Як Україна відбудувала Крим". Istpravda.com.ua. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- ↑ Calamur, Krishnadev (27 February 2014). "Crimea: A Gift To Ukraine Becomes A Political Flash Point". NPR. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ↑ (Ukrainian) Майже 60% росіян вважають, що Крим - це Росія Almost 60% of Russians believe, that Crimea - is Russian, Ukrayinska Pravda (10 September 2013)

- ↑ Wolczuk, Kataryna (August 31, 2004). "Catching up with 'Europe'? Constitutional Debates on the Territorial-Administrative Model in Independent Ukraine". Taylor & Francis Group. Retrieved December 16, 2006.

Wydra, Doris (November 11, 2004). "The Crimea Conundrum: The Tug of War Between Russia and Ukraine on the Questions of Autonomy and Self-Determination". - ↑ Eastern Europe, Russia and Central Asia 2004, Routledge, 2003, ISBN 1857431871 (page 540)

- 1 2 3 Russians in the Former Soviet Republics by Pål Kolstø, Indiana University Press, 1995, ISBN 0253329175 (page 194)

- ↑ Subtelny, Orest (2000). Ukraine: A History. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-8390-0.

- ↑ Ready To Cast Off, TIME Magazine, June 15, 1992

- 1 2 http://www.iccrimea.org/scholarly/nbelitser.html

- ↑ Laws of Ukraine. Verkhovna Rada law No. 93/95-вр: On the termination of the Constitution and some laws of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea. Adopted on 1995-03-17. (Ukrainian)

- ↑ Russia tells Ukraine to stay out of Nato, The Guardian (8 June 2006)

- ↑ Cheney urges divided Ukraine to unite against Russia 'threat. Associated Press. September 6, 2008.

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Levy, Clifford J. (2009-08-28). "Russia and Ukraine in Intensifying Standoff". Nytimes.com. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- ↑ Update: Ukraine, Russia ratify Black Sea naval lease, Kyiv Post (April 27, 2010)

- ↑ Ayres, Sabra (February 28, 2014). "Is it too late for Kiev to woo Russian-speaking Ukraine?". The Christian Science Monitor.

- ↑ "Olexandre Tourtchinov refuse de signer l’abrogation de la loi sur la politique linguistique".

- ↑ "Olexandre Tourtchinov demande d’urgence une nouvelle loi sur le statut des langues en Ukraine".

- ↑ "Putin orders military exercise as protesters clash in Crimea". Russia Herald. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ↑ "This is what it looked like when Russian military rolled through Crimea today (VIDEO)". UK Telegraph. Retrieved February 28, 2014.

- ↑ Charbonneau, Louis (28 February 2014). "UPDATE 2-U.N. Security Council to hold emergency meeting on Ukraine crisis". Reuters. Retrieved February 28, 2014.

- ↑ Higgons, Andrew, Grab for Power in Crimea Raises Secession Threat, New York Times, February 28, 2014, page A1; reporting was contributed by David M. Herszenhorn and Andrew E. Kramer from Kiev, Ukraine; Andrew Roth from Moscow; Alan Cowell from London; and Michael R. Gordon from Washington; with a graphic presentation of linguistic divisions of Ukraine and Crimea

- ↑ Radyuhin, Vladimir (March 1, 2014). "Crimean PM claims control of forces, asks Putin for help". Chennai, India. The Hindu. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

- ↑ "Ukraine army on full alert as Russia backs sending troops". BBC. March 1, 2014. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

- ↑ http://rt.com/news/churkin-unsc-russia-ukraine-683/ Yanukovich sent letter to Putin asking for Russian military presence in Ukraine

- ↑ "Movement of Russian armored vehicles in Crimea fully complies with agreements - Foreign Ministry". Russia Today. February 28, 2014. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

- ↑ Smale, Alison; Erlanger, Steven (1 March 2014). "Kremlin Clears Way for Force in Ukraine; Separatist Split Feared". New York Times. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ↑ Турчинов издал указ о незаконности назначения Аксенова премьером Крыма

- 1 2 "Russia 'demands surrender' of Ukraine's Crimea forces". BBC News. March 3, 2014. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- ↑ "'So why aren't they shooting?' is Putin's question, Ukrainians say". Kyiv Post. March 4, 2014. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ↑ "Ukraine resistance proves problem for Russia". BBC Online. March 4, 2014. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ↑ "'another view of the Ochakov - scuttled by Russian forces Wed night to block mouth of Donuzlav inlet". Twitter@elizapalmer. March 6, 2014. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- ↑ "'Ukraine crisis: Crimea parliament asks to join Russia". BBC. March 6, 2014. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- ↑ "'Ukraine crisis: 'Illegal' Crimean referendum condemned". BBC. March 6, 2014. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- ↑ "'Constitution of Ukraine - Title III". Government of Ukraine. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- 1 2 "'Russians Scuttle Another Ship to Block Ukrainian Fleet". Ukrainian Pravda. March 7, 2014. Retrieved March 7, 2014.

- ↑ "'Приложение 1 к Постановлению Верховной Рады Автономной Республики Крым от 6 марта 2014 года No 1702-6/14" (PDF). www.rada.crimea.ua. March 7, 2014. Retrieved March 7, 2014.

- ↑ "'Two choices in Crimean referendum: yes and yes". Kyiv Post. March 7, 2014. Retrieved March 7, 2014.

- ↑ https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/monkey-cage/wp/2014/03/03/crimean-autonomy-a-viable-alternative-to-war

- ↑ "Crimea referendum: Voters 'back Russian union'". BBC News. 16 March 2014. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- ↑ "Ukraine crisis: Do Crimea referendum figures add up?". BBC News. 17 March 2014. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- ↑ "Kremlin: Crimea and Sevastopol are now part of Russia, not Ukraine". CNN. 18 March 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ↑ "Ukraine: Putin signs Crimea annexation". BBC News. 21 March 2014. Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- ↑ Ukraine Votes to Dissolve Crimean Parliament. NBC News. 15 March 2014

- ↑ Lawmakers in Crimea Move Swiftly to Split From Ukraine New York Times, accessed 26 December 2014

- ↑ Crimean parliament to decide on appointment of autonomous republic's premier on Tuesday, Interfax Ukraine (7 November 2011)

- 1 2 "Autonomous Republic of Crimea – Information card". Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine. Retrieved February 22, 2007.

- ↑ Ziad, Waleed; Laryssa Chomiak (February 20, 2007). "A lesson in stifling violent extremism". CS Monitor. Retrieved March 26, 2007.

- ↑ Local government elections in Ukraine: last stage in the Party of Regions’ takeover of power, Centre for Eastern Studies (October 4, 2010)

- ↑ "Infobox card – Avtonomna Respublika Krym". Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine (in Ukrainian). Retrieved February 23, 2007.

- Subtelny, Orest (2000). Ukraine: A History. University of Toronto Press. p. 78. ISBN 0-8020-8390-0.

- "Autonomous Republic of Crimea – Information card". Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine. Retrieved February 22, 2007.

- Crimea, terra di mille etnie, 1993 di Giuseppe D'Amato in Il Diario del Cambiamento. Urss 1990 – Russia 1993. Greco&Greco editori, Milano, 1998. pp. 247–252. ISBN 88-7980-187-2 (The Diary of the Change. USSR 1990 – Russia 1993) Book in Italian.

- Crimea, la penisola regalata di Giuseppe D'Amato in L’EuroSogno e i nuovi Muri ad Est. L'Unione europea e la dimensione orientale. Greco&Greco editori, Milano, 2008. pp. 99–107 ISBN 978-88-7980-456-1 (The EuroDream and the new Walls at East. The European Union and the Eastern dimension) Book in Italian.

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Further reading

- (German) Stefan Albrecht, Michael Herdick: Ein Spielball der Mächte: Die Krim im Schwarzmeerraum (VI.-XV. Jahrhundert). =A Pawn of the Powers- The Crimea in the Black Sea Region (VI-XV. Century). In: Stefan Albrecht, Falko Daim, Michael Herdick (Hg.): Die Höhensiedlungen im Bergland der Krim. Umwelt, Kulturaustausch und Transformation am Nordrand des Byzantinischen Reiches. RGZM, Mainz 2013, S. 25-56. ISBN 978-3-884-67220-4 (with an Englisch and Russian Summary)

- (German) Stefan Albrecht, Michael Herdick, Rainer Schreg: Neue Forschungen auf der Krim. Geschichte und Gesellschaft im Bergland der südwestlichen Krim - eine Zusammenfassung. =New Researches on the Crimea. Synthesis: A Hypothetical Model of Competing Neighborhoods. In: Stefan Albrecht, Falko Daim, Michael Herdick (Hg.): Die Höhensiedlungen im Bergland der Krim. Umwelt, Kulturaustausch und Transformation am Nordrand des Byzantinischen Reiches. RGZM, Mainz 2013, S. 471-497. ISBN 978-3-884-67220-4 (with an Englisch and Russian Summary)

- (Russian) Bazilevich Basil Mitrofanovich. (1914) From the History of Moscow-Crimea Relations in the First Half of the 17th Century (Из истории московско-крымских отношений в первой половине XVII века) at Runivers.ru in DjVu and PDF formats

- (Russian) Bantysh-Kamensky Nikolay. (1893) Register of cases of Crimean court with 1474 to 1779 (Реестр делам крымского двора с 1474 по 1779 год) at Runivers.ru in DjVu and PDF formats

- (Russian) Berg Nikolai. (1858) Sevastopol album by N. Berg (Севастопольский альбом Н. Берга) at Runivers.ru in DjVu and PDF formats

- (Russian) Berezhkov Michael N.Plan for the conquest of the Crimea compiled during the reign of Emperor Alexis of Russia Slav scholar Yuri Krizhanich (План завоевания Крыма составленный в царствование государя Алексея Михайловича ученым славянином Юрием Крижаничем) at Runivers.ru in DjVu and PDF formats

- (Russian) Berezhkov Michael N. (1888) Russian captives and slaves in the Crimea (Русские пленники и невольники в Крыму) at Runivers.ru in DjVu and PDF formats

- (Russian) Bogdanovich Modest I. (1876) Eastern War 1853-1856 (Восточная война 1853-1856 гг.) at Runivers.ru in DjVu format

- (Russian) Dubrovin Nikolai Fedorovich. (1900) History of the Crimean War and the defense of Sevastopol (История Крымской войны и обороны Севастополя) at Runivers.ru in DjVu format

- (Russian) Dubrovin Nikolai Fedorovich. (1885–1889) Joining the Crimea to Russia (Присоединение Крыма к России) at Runivers.ru in DjVu format

External links

- Official

- www.ppu.gov.ua, official website of the Presidential Representative in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea (Ukrainian)

- ark.gp.gov.ua, official website of the Prosecutor's Office of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea (Ukrainian)

- www.rada.crimea.ua, official website of the Supreme Council of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea (Ukrainian) (Russian)

- qtmm.org, official website of the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People (Crimean Tatar) (Ukrainian) (Russian) (English)

- History

- Series about the recent political history of Crimea by Independent Analytical Center for Geopolitical Studies “Borysfen Intel”

- Historical footage of Crimea, 1918, filmportal.de

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|