Cresap's War

- For the 1774 conflict also known as "Cresap's War," see Lord Dunmore's War.

| Cresap's War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

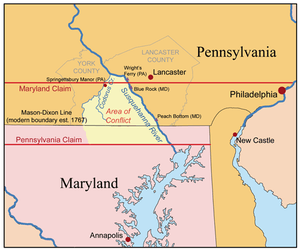

Map showing the area disputed between Maryland and Pennsylvania during Cresap's War. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Heavy | Heavy | ||||||

Cresap's War (also known as the Conojocular War—from the Conejohela Valley where it was located (mainly) along the south (right) bank) was a border conflict between Pennsylvania and Maryland, fought in the 1730s. Hostilities erupted in 1730 with a series of violent incidents prompted by disputes over property rights and law enforcement, and escalated through the first half of the decade, culminating in the deployment of military forces by Maryland in 1736 and by Pennsylvania in 1737. The armed phase of the conflict ended in May 1738 with the intervention of King George II, who compelled the negotiation of a cease-fire. A final settlement was not achieved until 1767 when the Mason–Dixon line was recognized as the permanent boundary between the two colonies.[1]

Background

Pennsylvania's Charter (1681) specified that the colony was bounded "on the South by a Circle drawne at twelve miles [19 km] distance from New Castle Northward and Westward unto the beginning of the fortieth degree of Northern Latitude, and then by a streight Line Westward...."[2] Later surveys established that the town of New Castle in fact lay a full 25 miles (40 km) south of the fortieth parallel, setting the stage for a boundary dispute. Maryland insisted that the boundary be drawn at the fortieth parallel as specified in the Charter, while Pennsylvania proposed that it be drawn by an elaborate method which purported to compensate for the geographic misunderstanding on which the Charter had been based. This proposal placed the boundary near 39 36', creating a twenty-eight mile wide strip of disputed territory.[3]

Because the fortieth parallel lay north of the city of Philadelphia, Maryland pressed its claim most seriously in the sparsely inhabited lands west of the Susquehanna River. By the late 1710s, rumors had begun to reach the Pennsylvania Assembly that Maryland was planning to establish settlements in the disputed area near the river. In response, Pennsylvania attempted to bolster its claim to the territory by organizing a proprietorial manor along the Codorus Creek, just west of the river, in 1722. This action prompted a crisis in relations between the two colonies, leading to a royal proclamation in 1724 which prohibited both colonies from establishing new settlements in the area until a boundary had been surveyed. However, the two sides failed to reach agreement on the location of the boundary, and unauthorized settlement recommenced within a short time.[1]

Triggering violence

In 1726, the English born Quaker minister John Wright and two associates with their families settled near the river and moved from C. They'd been coming to the birding swarms along the Conejohela Flats since 1724 and had made friends and converted an appreciable number of Indians, most by working their way through the marshy shallows on the opposite (west or right) bank of the Susquehanna. Sometime after building a house and planting a farm, probably with the help of their Indian friends in the second year there, Wright ended up building two medium-to-large Dugout (boat)dugout canoes kept and tied off on either bank, creating the seeds of an ad hoc passenger ferry business for those desiring to cross. Sometime few settlers moved across, settling mainly a few miles to the north along Conestoga Creek, but traffic grew sufficient to officially apply for a ferry license in 1730.

Settlement across picked up significantly that year, probably with the promise of regular ferry service across the Susquehanna, greatly easing transportation difficulties, but the inflow alarmed Lord Baltimore about his ability to assert control and collect incomes from the disputed area. By midsummer of 1730, a number of Pennsylvania Dutch settler families had crossed the river and taken up residence.[4] Determined to counter this development, a Marylander, Thomas Cresap, opened a second ferry service at Blue Rock, about four miles (6 km) south of Wright's Ferry.

Owing to the royal proclamation of 1724, the Pennsylvania settlers did not have clear title to the lands that they occupied. Apparently in defiance of the proclamation, Maryland granted Cresap title to 500 acres (2 km2) along the west bank of the river,[5] much of which was already inhabited. Cresap began to act as a land agent, persuading many Pennsylvania Dutch to purchase their farms from him, thus obtaining title under Maryland law, and began collecting quit-rents (an early form of property tax) for Maryland. In response, Pennsylvania authorities at Wright's Ferry began to issue "tickets" to new settlers which, while not granting immediate title, promised to award title as soon as the area was officially opened to settlement.[6]

Outbreak of hostilities

Sometime in late October, 1730, Cresap was attacked on his ferry boat by two Pennsylvanians.[7] According to Cresap's Maryland deposition, Cresap and one of his workmen were hailed by the Pennsylvanians and began rowing the two men from the east to the west. Sixty yards into the trip, the Pennsylvanians turned their guns on the Marylanders and a fight ensued with Cresap attempting to use the oars to defend himself. After a short struggle, both Marylanders ended up in the water, holding on to the boat to keep from drowning. The Pennsylvanians tried to force Cresap to let go of the boat, and when Cresap asked if they intended to murder him, one swore that he did. Cresap eventually escaped when the boat drifted to shallow water near a large rock where Cresap was stranded for several hours until rescued by a friendly Indian.

It would become clear in later testimony that the target of the attack was actually Cresap's workman who was wanted by a Lancaster county landowner for reasons not entirely clear (possibly debts). This workman was captured by the Pennsylvanians and carried forcibly away.

Cresap was dissatisfied by the response of the Pennsylvania magistrate to whom he reported the attack. Although the magistrate eventually signed warrants that brought the two Pennsylvanians to court, he first stated that "he knew no reason he (Cresap) had to expect any justice there, since he was a liver in Maryland."; a statement that the Governor of Maryland would later key on in a letter to the Governor of Pennsylvania. Significantly, Cresap filed charges with Maryland authorities, claiming that Pennsylvania officials had conspired with the attackers and with local native tribes to drive him from the area.,[8] From this point onward, Cresap would maintain that as a resident of Maryland, he was not bound by Pennsylvania law and was not obliged to cooperate with Pennsylvania's law enforcement officers.

1732 agreement

In 1732 the proprietary governor of Maryland, Charles Calvert, 5th Baron Baltimore, signed a provisional agreement with William Penn's sons, which drew a line somewhere in between and renounced the Calvert claim to Delaware. But later, Lord Baltimore claimed that the document he had signed did not contain the terms he had agreed to, and refused to put the agreement into effect. Beginning in the mid-1730s, violence erupted between settlers claiming various loyalties to Maryland and Pennsylvania. The border conflict would be known as Cresap's War.

The issue remained unresolved until the Crown intervened in 1760, ordering Frederick Calvert, 6th Baron Baltimore to accept the 1732 agreement. Maryland's border with Delaware was to be based on the Transpeninsular Line and the Twelve-Mile Circle around New Castle. The Pennsylvania-Maryland border was defined as the line of latitude 15 miles south of the southernmost house in Philadelphia.[9]

Attempt to arrest Cresap

A witness named William Smith gave the following account about the attempted arrest of Cresap on January 29, 1733:

"a Considerable number of People being at least Twenty in Number as he verily believes came in a Violent manner & required the Doors to be opened and the said Cresap to Surrender himselfe to them, one of them Swearing he was Sheriff of Lancaster County And others saying that they were to be Supported in their proceedings by one Emerson a Lawyer in Pensylvania [sic] and that they were then fifty Men & if they were not Enough they would have five hundred there next Morning to take Cresap."[10]

Cresap did not back down, claiming that "his house was his castle and he would defend it." [10] The crowd forced their way into the house, causing Cresap to fire a gun into the crowd. In response, "one or more of the said Persons several times said and Swore they would hang the said Cresap and burn his house & all that were in it." [10]

German farmers renounce Cresap

Depositions of several Germans accuse Cresap and his relatives the Lowes of maltreatment.:[7]

- Frederick Lather paid Cresap for land in 1733. In 1736, one of Cresap's workers notified Lather that the land (with improvements) belonged to Cresap and that he and his family would be speedily removed.

- Balser Springler (Baltzer Spengler) built a house on the Codorus Creek in 1733 (in present day York PA). He was deprived of his land and improvements by Cresap and was forced to make provision elsewhere for support of himself and family.

- Catherine Schultz testified that in March 1736, fifteen armed men came looking for her husband Martin. When they could not find him, they broke a door, stole an 80 gallon Hogshead of rum, threatened to kill a servant, stole horses and a sled and used sled to carry the rum to John Low's.

- Michael Tanner settled a 200-acre (0.81 km2) tract six miles (10 km) southwest of Wrightsville in 1734. In 1735, Cresap surveyed his land to Daniel Low. Low and family dwelt in Tanner's house and Tanner was obliged to pay Low eight pounds or otherwise lose his buildings and improvements.

- Several non-Germans in Chester County testified that two agents of Maryland had offered residents land formerly occupied and cleared by Dutchmen. In one case, the agents had by letter recommended the deponent to Thomas Cresap to be shown land west of Susquehanna.

Arrival of Maryland militia

Two incursions of Maryland militia into present day York County, Pennsylvania are mentioned in depositions by Pennsylvania natives.:[7]

- A surveyor named Franklin accompanied by twenty Maryland militia was sighted near John Wright's plantation (near present day Wrightsville PA) on May 6, 1736. When questioned, they stated they were sent by authority of Lord Baltimore.

- Three hundred Maryland militia went to the plantation of John Hendricks (a short distance from Wrightsville) on Sep 5 1736. The militia were under the command of Col. Nathaniel Rigby and accompanied by the Sheriff of Baltimore. On the next day, the militia broke into two groups, one returned to Maryland and the second went west with the Sheriff of Baltimore. The second group was accused by Pennsylvanians of taking Linen and Pewter from Dutchmen on the pretense of dues owed to the state of Maryland.

Arrival of Pennsylvania militia

Cresap first obtained a patent from Maryland for a ferry at Peach Bottom, near the Patterson farm, then shot several of Patterson's horses. One of the Marylanders, Lowe, was arrested and jailed, but the other Marylanders broke into the jail and freed him.

Cresap then obtained one for "Blue Rock Ferry" and several hundred acres of land, about 3½ miles south of Wrightsville, forcibly took possession of John Hendricks' plantation at Wrightsville.[11]

Cresap was no Quaker by any means; he had previously "cleft" an assailant in Virginia with a broad-ax when clearing disputed land there.[11]

Lord Baltimore had been unwilling to entreat with Indians for what he took,[11] but in 1733, reached an accommodation with the Pennsylvanians, but by 1734, Cresap was again evicting settlers from their Lancaster and York county homes, rewarding his gang members with the properties.[11]

The sheriff of Lancaster County brought a posse to arrest Cresap, but when deputy Knowles Daunt was at the door, Cresap fired through it, wounding Daunt. The sheriff asked Mrs. Cresap for a candle, so that they could see to tend to Daunt's wounds, but Mrs. Cresap refused, "crying out that not only was she glad he had been hit, she would have preferred the wound had been to his heart."[11] When Daunt died, Pennsylvania Governor Gordon demanded that Maryland arrest Cresap for murder. Governor Ogle of Maryland responded by naming Cresap a captain in the Maryland militia.[11]

Cresap continued his raids, destroying barns and livestock, until Sheriff Samuel Smith raised a posse of 24 armed "non-Quakers" to arrest him on November 25, 1736. Unable to get him to surrender, they set his cabin on fire, and when he made a run for the river, they were upon him before he could launch a boat. He shoved one of his captors overboard, and cried, "Cresap's getting away", and the other deputies pummeled their peer with oars until the ruse was discovered. Removed to Lancaster, a blacksmith was fetched to put him in steel manacles, but Cresap knocked the blacksmith down in one blow. Once constrained in steel, he was hauled off to Philadelphia, and paraded through the streets before being imprisoned. His spirit unbroken, he announced, "Damn it, this is one of the prettiest towns in Maryland!"[11]

Resolution

Following Cresap's arrest, Maryland sent a petition to King George II requesting that he intervene to restore order pending the outcome of the Chancery suit. On August 18, 1737, the king issued a proclamation instructing the governments of both colonies to cease hostilities.[12] Sporadic violence continued, prompting both sides to petition the king for further intervention. In response, the royal Committee for Plantation Affairs organized direct negotiations between the two colonies, which resulted in the signing of a peace agreement in London on May 25, 1738. This agreement provided for an exchange of prisoners and the drawing of a provisional boundary fifteen miles south of the city of Philadelphia. Each side agreed to respect the other's authority to conduct law enforcement and grant title to land on its own side of this boundary, pending the final action of the Chancery Court.[13]

Because Blue Rock Ferry lay well to the north of the provisional boundary, Cresap did not return to the area following his release in the prisoner exchange. In 1750, the Chancery Court upheld the validity of the 1732 agreement, which became the basis on which Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon surveyed the modern boundary (the Mason–Dixon line) between Pennsylvania and Maryland in 1767. Today the conflict area is part of York County, Pennsylvania.

Cresap's son Michael played a prominent role in Lord Dunmore's War (1774).[11] For this reason some historians also refer to the 1774 conflict as "Cresap's War."

References

- 1 2 Paul Doutrich (1986). "Cresap's War: Expansion and Conflict in the Susquehanna Valley,". Pennsylvania History (Cip.cornell.edu) 53: 89–104.

- ↑ "The Avalon Project : Documents in Law, History and Diplomacy". Yale.edu. Retrieved 2015-05-21.

- ↑ "The Bounday Disputes of Colonial Maryland". Chriswhong.com. Retrieved 2015-05-21.

- ↑ "1700-1749 - The York Daily Record". Ydr.com. Retrieved 2015-05-21.

- ↑ Kenneth P. Bailey, Thomas Cresap: Maryland Frontiersman, Cristopher Publishing, 1944, p. 32.

- ↑ Franklin Ellis and Samuel Evans, History of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, Everts & Peck, 1883.

- 1 2 3 Pennsylvania Archives Series 1 Vol 1, By Samuel Hazard, William Henry Egle, Pennsylvania Dept. of Public Instruction, 1852, Pages 311-313, 352-367, 412-421, 462-468, 476, 487, 489-494, 499-535

- ↑ Kenneth P. Bailey, Thomas Cresap: Maryland Frontiersman, Cristopher Publishing, 1944, pp. 32--36.

- ↑ Hubbard, Bill, Jr. (2009). American Boundaries: the Nation, the States, the Rectangular Survey. University of Chicago Press. pp. 20–23. ISBN 978-0-226-35591-7.

- 1 2 3 "Archives of Maryland, Volume 0028, Page 0062 - Proceedings of the Council of Maryland, 1732:1753". Aomol.msa.maryland.gov. 2014-10-31. Retrieved 2015-05-21.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 John Gibson, ed., History of York County, Pennsylvania, F.A. Battey Publishing Co., 1886. pp. 602-604.

- ↑ Proceedings of the Council of Maryland 28(1732--1753), pp. 130--133.

- ↑ Proceedings of the Council of Maryland 28(1732--1753), pp. 145--149.