Creation–evolution controversy

| Part of a series on | ||||

| Creationism | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Types | ||||

| Biblical cosmology | ||||

| Creation science | ||||

| Creation–evolution controversy | ||||

| Religious views | ||||

|

||||

| ||||

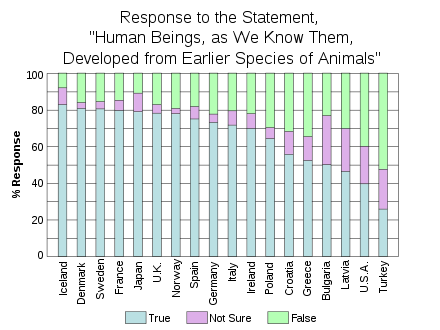

The creation–evolution controversy (also termed the creation vs. evolution debate or the origins debate) involves a recurring cultural, political, and theological dispute about the origins of the Earth, of humanity, and of other life. The evolution-creation controversy is almost exclusively an invention and problem within American-Protestant religious communities, outside of which such a controversy largely does not exist. The level of support for evolution is extremely high within the scientific community[1][2][3][4] and in academia.[5] While the controversy has a long history,[6][7] today it is mainly over what constitutes good science education,[8][9] with the politics of creationism primarily focusing on the teaching of creation and evolution in public education.[10][11][12][13][14] Among majority-Christian countries, the debate is most prominent in the United States, and to a lesser extent in Europe and elsewhere,[15] and is often portrayed as part of a culture war.[16] Parallel controversies also exist in some other religious communities, such as the more fundamentalist branches of Judaism[17] and Islam.[18]

Christian fundamentalists dispute the evidence of common descent of humans and other animals as demonstrated in modern paleontology, genetics, histology and cladistics and those other sub-disciplines which are based upon the conclusions of modern evolutionary biology, geology, cosmology, and other related fields. They argue for the Abrahamic accounts of creation, framing them as reputable science ("creation science").

The Catholic Church recognizes the existence of evolution. Pope Francis has stated: "God is not a divine being or a magician, but the Creator who brought everything to life...Evolution in nature is not inconsistent with the notion of creation, because evolution requires the creation of beings that evolve."[19][20] The rules of genetic evolutionary inheritance were first discovered by a Catholic priest, the Augustinian monk Gregor Mendel, who is known today as the founder of modern genetics.

A 2014 Gallup survey reports, "More than four in 10 Americans continue to believe that God created humans in their present form 10,000 years ago, a view that has changed little over the past three decades. Half of Americans believe humans evolved, with the majority of these saying God guided the evolutionary process. However, the percentage who say God was not involved is rising."[21]

The debate is sometimes portrayed as being between science and religion, but as the United States National Academy of Sciences states:

Today, many religious denominations accept that biological evolution has produced the diversity of living things over billions of years of Earth's history. Many have issued statements observing that evolution and the tenets of their faiths are compatible. Scientists and theologians have written eloquently about their awe and wonder at the history of the universe and of life on this planet, explaining that they see no conflict between their faith in God and the evidence for evolution. Religious denominations that do not accept the occurrence of evolution tend to be those that believe in strictly literal interpretations of religious texts.— National Academy of Sciences, Science, Evolution, and Creationism[22]

History

The creation–evolution controversy began in Europe and North America in the late 18th century, when new interpretations of geology led to various theories of an ancient earth, and extinctions demonstrated in the fossil geological sequence prompted early ideas of evolution, notably Lamarckism. In England these ideas of continuing change were at first seen as a threat to the existing "fixed" social order, and both church and state repressed them.[23] Conditions gradually eased, and in 1844 Robert Chambers's controversial Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation popularised the idea of transmutation of species. The scientific establishment at first dismissed it scornfully and the Church of England reacted with fury, but many Unitarians, Quakers and Baptists—groups opposed to the privileges of the established church—favoured its ideas of God acting through such laws.[24][25]

Contemporary reaction to Darwin

| “ | By the end of the 19th century, there was no serious scientific opposition to the basic evolutionary tenets of descent with modification and the common ancestry of all forms of life. | ” | |

.jpg)

The publication of Darwin's On the Origin of Species in 1859 brought scientific credibility to evolution, and made it a respectable field of study.[27]

Despite the intense interest in the religious implications of Darwin's book, theological controversy over higher criticism set out in Essays and Reviews (1860) largely diverted the Church of England's attention. Some of the liberal Christian authors of that work expressed support for Darwin, as did many Nonconformists. The Reverend Charles Kingsley, for instance, openly supported the idea of God working through evolution.[28] Other Christians opposed the idea, and even some of Darwin's close friends and supporters—including Charles Lyell and Asa Gray—initially expressed reservations about some of his ideas.[29] Gray later became a staunch supporter of Darwin in America, and collected together a number of his own writings to produce an influential book, Darwiniana (1876). These essays argued for a conciliation between Darwinian evolution and the tenets of theism, at a time when many on both sides perceived the two as mutually exclusive.[30] Gray said that investigation of physical causes was not opposed to the theological view and the study of the harmonies between mind and Nature, and thought it "most presumable that an intellectual conception realized in Nature would be realized through natural agencies."[31] Thomas Huxley, who strongly promoted Darwin's ideas while campaigning to end the dominance of science by the clergy, coined the term agnostic to describe his position that God's existence is unknowable. Darwin also took this position,[29] but prominent atheists including Edward Aveling and Ludwig Büchner also took up evolution and it was criticised, in the words of one reviewer, as "tantamount to atheism."[32][33][34][35] Following the lead of figures such as St. George Jackson Mivart and John Augustine Zahm, Roman Catholics in the United States became accepting of evolution itself while ambivalent towards natural selection and stressing humanity's divinely imbued soul.[36] The Catholic Church never condemned evolution, and initially the more conservative-leaning Catholic leadership in Rome held back, but gradually adopted a similar position.[36][37]

During the late 19th century evolutionary ideas were most strongly disputed by the premillennialists, who held to a prophecy of the imminent return of Christ based on a form of Biblical literalism, and were convinced that the Bible would be invalidated if any error in the Scriptures was conceded. However, hardly any of the critics of evolution at that time were as concerned about geology, freely granting scientists any time they needed before the Edenic creation to account for scientific observations, such as fossils and geological findings.[38] In the immediate post-Darwinian era, few scientists or clerics rejected the antiquity of the earth, the progressive nature of the fossil record.[39] Likewise, few attached geological significance to the Biblical flood, unlike subsequent creationists.[39] Evolutionary skeptics, creationist leaders and skeptical scientists were usually either willing to adopt a figurative reading of the first chapter of the Book of Genesis, or allowed that the six days of creation were not necessarily 24-hour days.[40]

Science professors at liberal northeastern universities almost immediately embraced the theory of evolution and introduced it to their students. However, some people in parts of the south and west of the United States, which had been influenced by the preachings of Christian fundamentalist evangelicals, rejected the theory as immoral.[41]

Creationism in theology

At the beginning of the 19th century debate had started to develop over applying historical methods to Biblical criticism, suggesting a less literal account of the Bible. Simultaneously, the developing science of geology indicated the Earth was ancient, and religious thinkers sought to accommodate this by day-age creationism or gap creationism. Neptunianist catastrophism, which had earlier proposed that a universal flood could explain all geological features, gave way to ideas of geological gradualism (introduced in 1795 by James Hutton) based upon the erosion and depositional cycle over millions of years, which gave a better explanation of the sedimentary column. Biology and the discovery of extinction (first described in the 1750s and put on a firm footing by Georges Cuvier in 1796) challenged ideas of a fixed immutable Aristotelian "great chain of being." Natural theology had earlier expected that scientific findings based on empirical evidence would help religious understanding. These differences led some to increasingly regard science and theology as concerned with different, non-competitive domains.

When most scientists came to accept evolution (by around 1875), European theologians generally came to accept evolution as an instrument of God. Pope Leo XIII, for instance, referred to longstanding Christian thought that scriptural interpretations could be reevaluated in the light of new knowledge, and Roman Catholics came around to acceptance of human evolution subject to direct creation of the soul. In the United States the development of the racist Social Darwinian eugenics movement led a number of Catholics to reject evolution.[29] In this enterprise they received little aid from conservative Christians in Great Britain and Europe. In Britain this has been attributed to their minority status leading to a more tolerant, less militant theological tradition.[42] In his speech at the Pontifical Academy of Sciences in 2014, Pope Francis declared that he accepted the Big Bang theory and the theory of evolution and God was not “a magician with a magic wand”.[43]

Development of creationism in the United States

At first in the U.S., evangelical Christians paid little attention to the developments in geology and biology, being more concerned with the rise of higher Biblical criticism which questioned the belief in the Bible as literal truth. Those criticising these approaches took the name "fundamentalist"—originally coined by its supporters to describe a specific package of theological beliefs that developed into a movement within the Protestant community of the United States in the early part of the 20th century, and which had its roots in the Fundamentalist–Modernist Controversy of the 1920s and 1930s.[44] The term usually has a religious connotation indicating unwavering attachment to a set of irreducible beliefs.[45]

Up until the early mid-20th century mainline denominations within the United States showed little official resistance to evolution. Around the start of the 20th century some evangelical scholars had ideas accommodating evolution, such as B. B. Warfield who saw it as a natural law expressing God's will. By then most U.S. high school and college biology classes taught scientific evolution, but several factors, including the rise of Christian fundamentalism and social factors of changes and insecurity in more traditionalist Bible Belt communities, led to a backlash. The numbers of children receiving secondary education increased rapidly, and parents who had fundamentalist tendencies or who opposed social ideas of what was called "survival of the fittest" had real concerns about what their children were learning about evolution.[29]

British creationism

The main British creationist movement in this period, the Evolution Protest Movement (EPM), formed in the 1930s[42] out of the Victoria Institute, or Philosophical Society of Great Britain (founded in 1865 in response to the publication of Darwin's On the Origin of Species in 1859 and of Essays and Reviews in 1860). The Victoria Institute had the stated objective of defending "the great truths revealed in Holy Scripture ... against the opposition of Science falsely so called." Although it did not officially oppose evolution, it attracted a number of scientists sceptical of Darwinism, including John William Dawson and Arnold Guyot.[46] It reached a high point of 1,246 members in 1897, but quickly plummeted to less than one third of that figure in the first two decades of the twentieth century.[46] Although it was anti-evolution at first, the institute joined the theistic evolution camp by the 1920s, which led to the development of the Evolution Protest Movement in reaction. Amateur ornithologist Douglas Dewar, the main driving force within the EPM, published a booklet entitled Man: A Special Creation (1936) and engaged in public speaking and debates with supporters of evolution. In the late 1930s he resisted American creationists' call for acceptance of flood geology, which later led to conflict within the organisation. Despite trying to win the public endorsement of C. S. Lewis, the most prominent Christian apologist of his day, by the mid-1950s the EPM came under control of schoolmaster/pastor Albert G. Tilney, whose dogmatic and authoritarian style ran the organisation "as a one-man band," rejecting flood geology, unwaveringly promoting gap creationism, and reducing the membership to lethargic inactivity.[47] It was renamed Creation Science Movement (CSM) in 1980, under the chairmanship of David Rosevear, who holds a Ph.D. in organometallic chemistry from the University of Bristol. By the mid-1980s the CSM had formally incorporated flood geology into its "Deed of Trust" (which all officers had to sign) and condemned gap creationism and day-age creationism as unscriptural.

United States legal challenges and their consequences

In 1925, Tennessee passed a statute called the Butler Act, which prohibited the teaching of the theory of evolution in all schools in the state. Later that year, a similar law was passed in Mississippi, and likewise, Arkansas in 1927. In 1968, these "anti-monkey" laws were struck down by the Supreme Court of the United States as unconstitutional, "because they established a religious doctrine violating both the First and Fourth Amendments to the United States Constitution."[48]

The modern struggle of religious fundamentalists accepting creationism, to get their rejection of evolution accepted as legitimate science within education institutions in the U.S., has been highlighted through a series of important court cases.

Butler Act and Scopes monkey trial

In the aftermath of World War I, the Fundamentalist–Modernist Controversy had brought a surge of opposition to the idea of evolution, and following the campaigning of William Jennings Bryan several states introduced legislation prohibiting the teaching of evolution. By 1925, such legislation was being considered in 15 states, and had passed in some states, such as Tennessee.[49] The American Civil Liberties Union offered to defend anyone who wanted to bring a test case against one of these laws. John T. Scopes accepted, and he confessed to teaching his Tennessee class evolution in defiance of the Butler Act. The textbook in question was George William Hunter's A Civic Biology: Presented in Problems (1914). The trial was widely publicized by H. L. Mencken among others, and is commonly referred to as the Scopes Monkey Trial. Scopes was convicted but the widespread publicity galvanized proponents of evolution. When the case was appealed to the Tennessee Supreme Court, the Court overturned the decision on a technicality (the judge had assessed the minimum $100 fine instead of allowing the jury to assess the fine).[50]

Although it overturned the conviction, the Court decided that the law was not in violation of the Religious Preference provisions of the Tennessee Constitution (Section 3 of Article 1), which stated "that no preference shall ever be given, by law, to any religious establishment or mode of worship."[51] The Court, applying that state constitutional language, held:

We are not able to see how the prohibition of teaching the theory that man has descended from a lower order of animals gives preference to any religious establishment or mode of worship. So far as we know, there is no religious establishment or organized body that has in its creed or confession of faith any article denying or affirming such a theory.... Protestants, Catholics, and Jews are divided among themselves in their beliefs, and that there is no unanimity among the members of any religious establishment as to this subject. Belief or unbelief in the theory of evolution is no more a characteristic of any religious establishment or mode of worship than is belief or unbelief in the wisdom of the prohibition laws. It would appear that members of the same churches quite generally disagree as to these things.... Furthermore, [the Butler Act] requires the teaching of nothing. It only forbids the teaching of evolution of man from a lower order of animals.... As the law thus stands, while the theory of evolution of man may not be taught in the schools of the State, nothing contrary to that theory [such as Creationism] is required to be taught.

... It is not necessary now to determine the exact scope of the Religious Preference clause of the Constitution ... Section 3 of Article 1 is binding alike on the Legislature and the school authorities. So far we are clear that the Legislature has not crossed these constitutional limitations.

— Scopes v. State, 289 S.W. 363, 367 (Tenn. 1927).[52]

The interpretation of the Establishment Clause of the United States Constitution up to that time was that the government could not establish a particular religion as the State religion. The Tennessee Supreme Court's decision held in effect that the Butler Act was constitutional under the state Constitution's Religious Preference Clause, because the Act did not establish one religion as the "State religion."[53] As a result of the holding, the teaching of evolution remained illegal in Tennessee, and continued campaigning succeeded in removing evolution from school textbooks throughout the United States.[54][55][56][57]

Epperson v. Arkansas

In 1968, the United States Supreme Court invalidated a forty-year-old Arkansas statute that prohibited the teaching of evolution in the public schools. A Little Rock, Arkansas, high school biology teacher, Susan Epperson, filed suit charging the law violated the federal constitutional prohibition against establishment of religion as set forth in the Establishment Clause. The Little Rock Ministerial Association supported Epperson's challenge, declaring, "to use the Bible to support an irrational and an archaic concept of static and undeveloping creation is not only to misunderstand the meaning of the Book of Genesis, but to do God and religion a disservice by making both enemies of scientific advancement and academic freedom."[58] The Court held that the United States Constitution prohibits a state from requiring, in the words of the majority opinion, "that teaching and learning must be tailored to the principles or prohibitions of any religious sect or dogma."[59] But the Supreme Court decision also suggested that creationism could be taught in addition to evolution.[60]

Daniel v. Waters

Daniel v. Waters was a 1975 legal case in which the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit struck down Tennessee's law regarding the teaching of "equal time" of evolution and creationism in public school science classes because it violated the Establishment Clause. Following this ruling, creationism was stripped of overt biblical references and renamed "Creation Science," and several states passed legislative acts requiring that this be given equal time with the teaching of evolution.

Creation science

As biologists grew more and more confident in evolution as the central defining principle of biology,[61][62] American membership in churches favoring increasingly literal interpretations of scripture also rose, with the Southern Baptist Convention and Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod outpacing all other denominations.[63] With growth and increased finances, these churches became better equipped to promulgate a creationist message, with their own colleges, schools, publishing houses, and broadcast media.[64]

In 1961, the first major modern creationist book was published: John C. Whitcomb and Henry M. Morris' influential The Genesis Flood: The Biblical Record and Its Scientific Implications. The authors argued that creation was literally 6 days long, that humans lived concurrently with dinosaurs, and that God created each 'kind' of life individually.[65][66] On the strength of this, Morris became a popular speaker, spreading anti-evolutionary ideas at fundamentalist churches, colleges, and conferences.[65] Morris' Creation Science Research Center (CSRC) rushed publication of biology textbooks that promoted creationism.[67] Ultimately, the CSRC broke up over a divide between sensationalism and a more intellectual approach, and Morris founded the Institute for Creation Research, which was promised to be controlled and operated by scientists.[68] During this time, Morris and others who supported flood geology adopted the terms "scientific creationism" and "creation science."[69] The "flood geology" theory effectively co-opted "the generic creationist label for their hyperliteralist views."[70][71]

Court cases

McLean v. Arkansas

In 1982, another case in Arkansas ruled that the Arkansas "Balanced Treatment for Creation-Science and Evolution-Science Act" (Act 590) was unconstitutional because it violated the Establishment Clause. Much of the transcript of the case was lost, including evidence from Francisco Ayala.

Edwards v. Aguillard

In the early 1980s, the Louisiana legislature passed a law titled the "Balanced Treatment for Creation-Science and Evolution-Science Act." The act did not require teaching either evolution or creationism as such, but did require that when evolutionary science was taught, creation science had to be taught as well. Creationists had lobbied aggressively for the law, arguing that the act was about academic freedom for teachers, an argument adopted by the state in support of the act. Lower courts ruled that the State's actual purpose was to promote the religious doctrine of creation science, but the State appealed to the Supreme Court.

In the similar case of McLean v. Arkansas (see above) the federal trial court had also decided against creationism. Mclean v. Arkansas was not appealed to the federal Circuit Court of Appeals, creationists instead thinking that they had better chances with Edwards v. Aguillard. In 1987 the United States Supreme Court ruled that the Louisiana act was also unconstitutional, because the law was specifically intended to advance a particular religion. At the same time, it stated its opinion that "teaching a variety of scientific theories about the origins of humankind to school children might be validly done with the clear secular intent of enhancing the effectiveness of science instruction," leaving open the door for a handful of proponents of creation science to evolve their arguments into the iteration of creationism that later came to be known as intelligent design.[72]

Intelligent design

In response to Edwards v. Aguillard, the neo-creationist intelligent design movement was formed around the Discovery Institute's Center for Science and Culture. It makes the claim that "certain features of the universe and of living things are best explained by an intelligent cause, not an undirected process such as natural selection."[74] It has been viewed as a "scientific" approach to creationism by creationists, but is widely rejected as unscientific by the science community—primarily because intelligent design cannot be tested and rejected like scientific hypotheses (see for example, List of scientific bodies explicitly rejecting Intelligent design).

Kansas evolution hearings

In the push by intelligent design advocates to introduce intelligent design in public school science classrooms, the hub of the intelligent design movement, the Discovery Institute, arranged to conduct hearings to review the evidence for evolution in the light of its Critical Analysis of Evolution lesson plans. The Kansas evolution hearings were a series of hearings held in Topeka, Kansas, May 5 to May 12, 2005. The Kansas State Board of Education eventually adopted the institute's Critical Analysis of Evolution lesson plans over objections of the State Board Science Hearing Committee, and electioneering on behalf of conservative Republican Party candidates for the Board.[75] On August 1, 2006, four of the six conservative Republicans who approved the Critical Analysis of Evolution classroom standards lost their seats in a primary election. The moderate Republican and Democrats gaining seats vowed to overturn the 2005 school science standards and adopt those recommended by a State Board Science Hearing Committee that were rejected by the previous board,[76] and on February 13, 2007, the Board voted 6 to 4 to reject the amended science standards enacted in 2005. The definition of science was once again limited to "the search for natural explanations for what is observed in the universe."[77]

Dover trial

Following the Edwards v. Aguillard decision by the United States Supreme Court, in which the Court held that a Louisiana law requiring that creation science be taught in public schools whenever evolution was taught was unconstitutional, because the law was specifically intended to advance a particular religion, creationists renewed their efforts to introduce creationism into public school science classes. This effort resulted in intelligent design, which sought to avoid legal prohibitions by leaving the source of creation to an unnamed and undefined intelligent designer, as opposed to God.[78] This ultimately resulted in the "Dover Trial," Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District, which went to trial on 26 September 2005 and was decided on 20 December 2005 in favor of the plaintiffs, who charged that a mandate that intelligent design be taught in public school science classrooms was an unconstitutional establishment of religion. The Kitzmiller v. Dover decision held that intelligent design was not a subject of legitimate scientific research, and that it "cannot uncouple itself from its creationist, and hence religious, antecedents."[79]

The December 2005 ruling in the Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District trial[80] supported the viewpoint of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and other science and education professional organizations that Teach the Controversy proponents seek to undermine the teaching of evolution[2][81] while promoting intelligent design,[82][83][84] and to advance an education policy for U.S. public schools that introduces creationist explanations for the origin of life to public-school science curricula.[80][85]

Texas Board of Education support for intelligent design

On March 27, 2009, the Texas Board of Education, by a vote of 13 to 2, voted that at least in Texas, textbooks must teach intelligent design alongside evolution, and question the validity of the fossil record. Don McLeroy, a dentist and chair of the board, said, "I think the new standards are wonderful ... dogmatism about evolution [has sapped] America's scientific soul." According to Science magazine, "Because Texas is the second-largest textbook market in the United States, publishers have a strong incentive to be certified by the board as 'conforming 100% to the state's standards'."[86] The 2009 Texas Board of Education hearings were chronicled in the 2012 documentary The Revisionaries.

Recent developments

The scientific consensus on the origins and evolution of life continues to be challenged by creationist organizations and religious groups who desire to uphold some form of creationism (usually young Earth creationism, creation science, old Earth creationism or intelligent design) as an alternative. Most of these groups are literalist Christians who believe the biblical account is inerrant, and more than one sees the debate as part of the Christian mandate to evangelize.[87][88] Some groups see science and religion as being diametrically opposed views that cannot be reconciled. More accommodating viewpoints, held by many mainstream churches and many scientists, consider science and religion to be separate categories of thought (non-overlapping magisteria), which ask fundamentally different questions about reality and posit different avenues for investigating it.[89]

More recently, the intelligent design movement has attempted an anti-evolution position that avoids any direct appeal to religion. Scientists argue that intelligent design does not represent any research program within the mainstream scientific community, and is still essentially creationism.[4][90] Its leading proponent, the Discovery Institute, made widely publicised claims that it was a new science, although the only paper arguing for it published in a scientific journal was accepted in questionable circumstances and quickly disavowed in the Sternberg peer review controversy, with the Biological Society of Washington stating that it did not meet the journal's scientific standards, was a "significant departure" from the journal's normal subject area and was published at the former editor's sole discretion, "contrary to typical editorial practices."[91] On August 1, 2005, U.S. President George W. Bush commented endorsing the teaching of intelligent design alongside evolution "I felt like both sides ought to be properly taught ... so people can understand what the debate is about."[8][92]

Viewpoints

In the controversy a number of divergent opinions can be recognised, regarding both the acceptance of scientific theories and religious practice.

Young Earth creationism

Young Earth creationism rejects completely the conventional scientific approach and argues for the belief that the Earth was created by God within the last 10,000 years, literally as described in Genesis, within the approximate timeframe of biblical genealogies (detailed for example in the Ussher chronology). Young Earth creationists often believe that the Universe has a similar age to the Earth's. Creationist cosmologies are attempts by some creationist thinkers to give the universe an age consistent with the Ussher chronology and other Young-Earth timeframes. This belief generally has a basis in biblical literalism.

Old Earth creationism

Old Earth creationism holds that the physical universe was created by God, but that the creation event of Genesis within 6 days is not to be taken strictly literally. This group generally accepts the age of the Universe and the age of the Earth as described by astronomers and geologists, but that details of the evolutionary theory are questionable. Old Earth creationists interpret the Genesis creation narrative in a number of ways, that each differ from the six, consecutive, 24-hour day creation of the young Earth creationist view.

Neo-creationism

Neo-creationists intentionally distance themselves from other forms of creationism, preferring to be known as wholly separate from creationism as a philosophy. They wish to re-frame the debate over the origins of life in non-religious terms and without appeals to scripture, and to bring the debate before the public. Neo-creationists may be either young Earth or old Earth creationists, and hold a range of underlying theological viewpoints (e.g. on the interpretation of the Bible). Neo-creationism currently exists in the form of the intelligent design movement, which has a 'big tent' strategy making it inclusive of many young Earth creationists (such as Paul Nelson and Percival Davis).

Theistic evolution

Theistic evolution is the general view that, instead of faith being in opposition to biological evolution, some or all classical religious teachings about God and creation are compatible with some or all of modern scientific theory, including, specifically, evolution. It generally views evolution as a tool used by a creator god, who is both the first cause and immanent sustainer/upholder of the universe; it is therefore well accepted by people of strong theistic (as opposed to deistic) convictions. Theistic evolution can synthesize with the day-age interpretation of the Genesis creation myth; most adherents consider that the first chapters of Genesis should not be interpreted as a "literal" description, but rather as a literary framework or allegory.

This position generally accepts the viewpoint of methodological naturalism, a long-standing convention of the scientific method in science.

Theistic evolutionists have frequently been prominent in opposing creationism (including intelligent design). Notable examples have been biologist Kenneth R. Miller and theologian John F. Haught, who testified for the plaintiffs in Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District. Another example is the Clergy Letter Project, an organization that has created and maintains a statement signed by American Christian clergy of different denominations rejecting creationism, with specific reference to points raised by intelligent design proponents. Theistic evolutionists have also been active in Citizens Alliances for Science that oppose the introduction of creationism into public school science classes (one example being evangelical Christian geologist Keith B. Miller, who is a prominent board member of Kansas Citizens for Science).

Agnostic evolution

Agnostic evolution is the position of acceptance of biological evolution, combined with the belief that it is not important whether God is, was, or will have been involved.[93]

Materialistic evolution

Materialistic evolution is the position of acceptance of biological evolution, combined with the position that the supernatural does not exist (a position common to philosophical naturalists, humanists and atheists).[94] It is a view championed by the New Atheists, who argue strongly that the creationist viewpoint is not only dangerous, but is completely rejected by science.

Arguments relating to the definition and limits of science

Critiques such as those based on the distinction between theory and fact are often leveled against unifying concepts within scientific disciplines. Principles such as uniformitarianism, Occam's razor or parsimony, and the Copernican principle are claimed to be the result of a bias within science toward philosophical naturalism, which is equated by many creationists with atheism.[95] In countering this claim, philosophers of science use the term methodological naturalism to refer to the long-standing convention in science of the scientific method. The methodological assumption is that observable events in nature are explained only by natural causes, without assuming the existence or non-existence of the supernatural, and therefore supernatural explanations for such events are outside the realm of science.[96] Creationists claim that supernatural explanations should not be excluded and that scientific work is paradigmatically close-minded.[97]

Because modern science tries to rely on the minimization of a priori assumptions, error, and subjectivity, as well as on avoidance of Baconian idols, it remains neutral on subjective subjects such as religion or morality.[98] Mainstream proponents accuse the creationists of conflating the two in a form of pseudoscience.[99]

Definitions

According to the National Academy of Sciences, terms that are used in describing the nature of science include:

| “ | Fact: In science, an observation that has been repeatedly confirmed and for all practical purposes is accepted as "true." Truth in science, however, is never final, and what is accepted as a fact today may be modified or even discarded tomorrow.

Hypothesis: A tentative statement about the natural world leading to deductions that can be tested. If the deductions are verified, it becomes more probable that the hypothesis is correct. If the deductions are incorrect, the original hypothesis can be abandoned or modified. Hypotheses can be used to build more complex inferences and explanations. Law: A descriptive generalization about how some aspect of the natural world behaves under stated circumstances. Theory: In science, a well-substantiated explanation of some aspect of the natural world that can incorporate facts, laws, inferences, and tested hypotheses. |

” |

Limitations of scientific endeavor

| “ | In science, explanations are limited to those based on observations and experiments that can be substantiated by other scientists. Explanations that cannot be based on empirical evidence are not a part of science. | ” |

| “ | The scientific method is a body of techniques for investigating phenomena, acquiring new knowledge, or correcting and integrating previous knowledge. To be termed scientific, a method of inquiry must be based on empirical and measurable evidence subject to specific principles of reasoning. What I believe in my heart must make sense in my mind. In other words, truth is not only a matter of offense, in that it makes certain assertions. It is also a matter of defense in that it must be able to make a cogent and sensible response to the counterpoints that are raised. Truth by definition excludes. | ” |

Theory vs. fact

The argument that evolution is a theory, not a fact, has often been made against the exclusive teaching of evolution.[100] The argument is related to a common misconception about the technical meaning of "theory" that is used by scientists. In common usage, "theory" often refers to conjectures, hypotheses, and unproven assumptions. In science, "theory" usually means "a plausible or scientifically acceptable general principle or body of principles offered to explain phenomena."[101]

Exploring this issue, paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould wrote:

| “ | Evolution is a theory. It is also a fact. And facts and theories are different things, not rungs in a hierarchy of increasing certainty. Facts are the world's data. Theories are structures of ideas that explain and interpret facts. Facts do not go away when scientists debate rival theories to explain them. Einstein's theory of gravitation replaced Newton's, but apples did not suspend themselves in mid-air, pending the outcome. And humans evolved from ape-like ancestors whether they did so by Darwin's proposed mechanism or by some other yet to be discovered. | ” |

Falsifiability

Philosopher of science Karl R. Popper set out the concept of falsifiability as a way to distinguish science and pseudoscience:[102][103] testable theories are scientific, but those that are untestable are not.[104] In Unended Quest, Popper declared "I have come to the conclusion that Darwinism is not a testable scientific theory but a metaphysical research programme, a possible framework for testable scientific theories," while pointing out it had "scientific character."[105]

In what one sociologist derisively called "Popper-chopping,"[106] opponents of evolution seized upon Popper's definition to claim evolution was not a science, and claimed creationism was an equally valid metaphysical research program.[107] For example, Duane Gish, a leading Creationist proponent, wrote in a letter to Discover magazine (July 1981): "Stephen Jay Gould states that creationists claim creation is a scientific theory. This is a false accusation. Creationists have repeatedly stated that neither creation nor evolution is a scientific theory (and each is equally religious)."[108]

Popper responded to news that his conclusions were being used by anti-evolutionary forces by affirming that evolutionary theories regarding the origins of life on earth were scientific because "their hypotheses can in many cases be tested."[109] Creationists claimed that a key evolutionary concept, that all life on Earth is descended from a single common ancestor, was not mentioned as testable by Popper, and claimed it never would be.[110]

In fact, Popper wrote admiringly of the value of Darwin's theory.[111] Only a few years later, Popper wrote, "I have in the past described the theory as 'almost tautological' ... I still believe that natural selection works in this way as a research programme. Nevertheless, I have changed my mind about the testability and logical status of the theory of natural selection; and I am glad to have an opportunity to make a recantation." His conclusion, later in the article is "The theory of natural selection may be so formulated that it is far from tautological. In this case it is not only testable, but it turns out to be not strictly universally true."[112]

Debate among some scientists and philosophers of science on the applicability of falsifiability in science continues.[113] Simple falsifiability tests for common descent have been offered by some scientists: for instance, biologist and prominent critic of creationism Richard Dawkins and J. B. S. Haldane both pointed out that if fossil rabbits were found in the Precambrian era, a time before most similarly complex lifeforms had evolved, "that would completely blow evolution out of the water."[114][115]

Falsifiability has caused problems for creationists: in his 1982 decision McLean v. Arkansas Board of Education, Judge William R. Overton used falsifiability as one basis for his ruling against the teaching of creation science in the public schools, ultimately declaring it "simply not science."[116]

Conflation of science and religion

Creationists commonly argue against evolution on the grounds that "evolution is a religion; it is not a science,"[117] in order to undermine the higher ground biologists claim in debating creationists, and to reframe the debate from being between science (evolution) and religion (creationism) to being between two equally religious beliefs—or even to argue that evolution is religious while intelligent design is not.[118][119] Those that oppose evolution frequently refer to supporters of evolution as "evolutionists" or "Darwinists."[117]

This is generally argued by analogy, by arguing that evolution and religion have one or more things in common, and that therefore evolution is a religion. Examples of claims made in such arguments are statements that evolution is based on faith, that supporters of evolution revere Darwin as a prophet, and that supporters of evolution dogmatically reject alternative suggestions out-of-hand.[120][121] These claims have become more popular in recent years as the neocreationist movement has sought to distance itself from religion, thus giving it more reason to make use of a seemingly anti-religious analogy.[122]

In response, supporters of evolution have argued that no scientist's claims, including Darwin's, are treated as sacrosanct, as shown by the aspects of Darwin's theory that have been rejected or revised by scientists over the years, to form first neo-Darwinism and later the modern evolutionary synthesis.[123][124]

Appeal to consequences

A number of creationists have blurred the boundaries between their disputes over the truth of the underlying facts, and explanatory theories, of evolution, with their purported philosophical and moral consequences. This type of argument is known as an appeal to consequences, and is a logical fallacy. Examples of these arguments include those of prominent creationists such as Ken Ham[125] and Henry M. Morris.[126]

Disputes relating to science

| Part of a series on |

| Evolutionary biology |

|---|

|

|

History of evolutionary theory |

|

Fields and applications

|

|

Many creationists strongly oppose certain scientific theories in a number of ways, including opposition to specific applications of scientific processes, accusations of bias within the scientific community,[127] and claims that discussions within the scientific community reveal or imply a crisis. In response to perceived crises in modern science, creationists claim to have an alternative, typically based on faith, creation science, or intelligent design. The scientific community has responded by pointing out that their conversations are frequently misrepresented (e.g. by quote mining) in order to create the impression of a deeper controversy or crisis, and that the creationists' alternatives are generally pseudoscientific.

Biology

Disputes relating to evolutionary biology are central to the controversy between creationists and the scientific community. The aspects of evolutionary biology disputed include common descent (and particularly human evolution from common ancestors with other members of the great apes), macroevolution, and the existence of transitional fossils.

Common descent

[The] Discovery [Institute] presents common descent as controversial exclusively within the animal kingdom, as it focuses on embryology, anatomy, and the fossil record to raise questions about them. In the real world of science, common descent of animals is completely noncontroversial; any controversy resides in the microbial world. There, researchers argued over a variety of topics, starting with the very beginning, namely the relationship among the three main branches of life.— John Timmer, Evolution: what's the real controversy?[128]

A group of organisms is said to have common descent if they have a common ancestor. A theory of universal common descent based on evolutionary principles was proposed by Charles Darwin and is now generally accepted by biologists. The most recent common ancestor of all living organisms is believed to have appeared about 3.9 billion years ago. With a few exceptions (e.g. Michael Behe) the vast majority of creationists reject this theory in favor of the belief that a common design suggests a common designer (God), for all thirty million species.[129][130][131] Other creationists allow evolution of species, but say that it was specific "kinds" or baramin that were created. Thus all bear species may have developed from a common ancestor that was separately created.

Evidence of common descent includes evidence from genetics, fossil records, comparative anatomy, geographical distribution of species, comparative physiology and comparative biochemistry.

Human evolution

Human evolution is the study of the biological evolution of humans as a distinct species from its common ancestors with other animals. Analysis of fossil evidence and genetic distance are two of the means by which scientists understand this evolutionary history.

Fossil evidence suggests that humans' earliest hominid ancestors may have split from other primates as early as the late Oligocene, circa 26 to 24 Ma, and that by the early Miocene, the adaptive radiation of many different hominoid forms was well underway.[132] Evidence from the molecular dating of genetic differences indicates that the gibbon lineage (family Hylobatidae) diverged between 18 and 12 Ma, and the orangutan lineage (subfamily Ponginae) diverged about 12 Ma. While there is no fossil evidence thus far clearly documenting the early ancestry of gibbons, fossil proto-orangutans may be represented by Sivapithecus from India and Griphopithecus from Turkey, dated to around 10 Ma. Molecular evidence further suggests that between 8 and 4 Ma, first the gorillas, and then the chimpanzee (genus Pan) split from the line leading to the humans.[133] We have no fossil record of this divergence, but distinctively hominid fossils have been found dating to 3.2 Ma (see Lucy) and possibly even earlier, at 6 or 7 Ma (see Toumaï).[134] Comparisons of DNA show that 99.4 percent of the coding regions are identical in chimpanzees and humans (95–96% overall[135][136]), which is taken as strong evidence of recent common ancestry.[137] Today, only one distinct human species survives, but many earlier species have been found in the fossil record, including Homo erectus, Homo habilis, and Homo neanderthalensis.

Creationists dispute there is evidence of shared ancestry in the fossil evidence, and argue either that these are misassigned ape fossils (e.g. that Java Man was a gibbon[138]) or too similar to modern humans to designate them as distinct or transitional forms.[139] Creationists frequently disagree where the dividing lines would be.[140] Creation myths (such as the Book of Genesis) frequently posit a first man (Adam, in the case of Genesis) as an alternative viewpoint to the scientific account.

Creationists also dispute science's interpretation of genetic evidence in the study of human evolution. They argue that it is a "dubious assumption" that genetic similarities between various animals imply a common ancestral relationship, and that scientists are coming to this interpretation only because they have preconceived notions that such shared relationships exist. Creationists also argue that genetic mutations are strong evidence against evolutionary theory because the mutations required for major changes to occur would almost certainly be detrimental.[58]

Macroevolution

Many creationists accept the possibilities of microevolution within "kinds" but refuse to accept and have long argued against the possibility of macroevolution. Macroevolution is defined by the scientific community to be evolution that occurs at or above the level of species. Under this definition, macroevolution can be considered to be a fact, as evidenced by observed instances of speciation. Creationists tend to apply a more restrictive, if vaguer, definition of macroevolution, often relating to the emergence of new body forms or organs. The scientific community considers that there is strong evidence for even such more restrictive definitions, but the evidence for this is more complex.

Recent arguments against (such restrictive definitions of) macroevolution include the intelligent design (ID) arguments of irreducible complexity and specified complexity. Neither argument has been accepted for publication in a peer-reviewed scientific journal, and both arguments have been rejected by the scientific community as pseudoscience. When taken to court in an attempt to introduce ID into the classroom, the judge wrote "The overwhelming evidence at trial established that ID is a religious view, a mere re-labeling of creationism, and not a scientific theory."

Biologist Richard Dawkins published a book The Greatest Show on Earth: The Evidence for Evolution (2009) giving evidence for evolution and macroevolution.

Transitional fossils

It is commonly stated by critics of evolution that there are no known transitional fossils.[141][142] This position is based on a misunderstanding of the nature of what represents a transitional feature. A common creationist argument is that no fossils are found with partially functional features. It is plausible that a complex feature with one function can adapt a different function through evolution. The precursor to, for example, a wing, might originally have only been used for gliding, trapping flying prey, or mating display. Today, wings can still have all of these functions, but they are also used in active flight.

As another example, Alan Hayward stated in Creation and Evolution (1985) that "Darwinists rarely mention the whale because it presents them with one of their most insoluble problems. They believe that somehow a whale must have evolved from an ordinary land-dwelling animal, which took to the sea and lost its legs ... A land mammal that was in the process of becoming a whale would fall between two stools—it would not be fitted for life on land or at sea, and would have no hope for survival."[143] The evolution of whales has been documented in considerable detail, with Ambulocetus, described as looking like a three-metre long mammalian crocodile, as one of the transitional fossils.[144]

Although transitional fossils elucidate the evolutionary transition of one life-form to another, they only exemplify snapshots of this process. Due to the special circumstances required for preservation of living beings, only a very small percentage of all life-forms that ever have existed can be expected to be discovered. Thus, the transition itself can only be illustrated and corroborated by transitional fossils, but it will never be known in detail. Progressing research and discovery managed to fill in several gaps and continues to do so. Critics of evolution often cite this argument as being a convenient way to explain off the lack of 'snapshot' fossils that show crucial steps between species.

The theory of punctuated equilibrium developed by Stephen Jay Gould and Niles Eldredge is often mistakenly drawn into the discussion of transitional fossils. This theory pertains only to well-documented transitions within taxa or between closely related taxa over a geologically short period. These transitions, usually traceable in the same geological outcrop, often show small jumps in morphology between periods of morphological stability. To explain these jumps, Gould and Eldredge envisaged comparatively long periods of genetic stability separated by periods of rapid evolution. For example, the change from a creature the size of a mouse, to one the size of an elephant, could be accomplished over 60,000 years, with a rate of change too small to be noticed over any human lifetime. 60,000 years is too small a gap to be identified or identifiable in the fossil record.[145]

Experts in evolutionary theory have pointed out that even if it were possible for enough fossils to survive to show a close transitional change critics will never be satisfied, as the discovery of one "missing link" itself creates two more so-called "missing links" on either side of the discovery. Richard Dawkins says that the reason for this "losing battle" is that many of these critics are theists who "simply don't want to see the truth."

Geology

Many believers in young Earth creationism – a position held by the majority of proponents of flood geology – accept biblical chronogenealogies (such as the Ussher chronology, which in turn is based on the Masoretic version of the Genealogies of Genesis).[146][147] They believe that God created the universe approximately 6000 years ago, in the space of six days. Much of creation geology is devoted to debunking the dating methods used in anthropology, geology, and planetary science that give ages in conflict with the young Earth idea. In particular, creationists dispute the reliability of radiometric dating and isochron analysis, both of which are central to mainstream geological theories of the age of the Earth. They usually dispute these methods based on uncertainties concerning initial concentrations of individually considered species and the associated measurement uncertainties caused by diffusion of the parent and daughter isotopes. A full critique of the entire parameter-fitting analysis, which relies on dozens of radionuclei parent and daughter pairs, has not been done by creationists hoping to cast doubt on the technique.

The consensus of professional scientific organisations worldwide is that no scientific evidence contradicts the age of approximately 4.5 billion years.[1] Young Earth creationists reject these ages on the grounds of what they regard as being tenuous and untestable assumptions in the methodology. They have often quoted apparently inconsistent radiometric dates to cast doubt on the utility and accuracy of the method. Mainstream proponents who get involved in this debate point out that dating methods only rely on the assumptions that the physical laws governing radioactive decay have not been violated since the sample was formed (harking back to Lyell's doctrine of uniformitarianism). They also point out that the "problems" that creationists publicly mentioned can be shown to either not be problems at all, are issues with known contamination, or simply the result of incorrectly evaluating legitimate data. The fact that the various methods of dating give essentially identical or near identical readings is not addressed in creationism.

Other sciences

Cosmology

While young Earth creationists believe that the Universe was created by the Judeo-Christian God approximately 6000 years ago, the current scientific consensus is that the Universe as we know it emerged from the Big Bang 13.8 billion years ago. The recent science of nucleocosmochronology is extending the approaches used for carbon-14 and other radiometric dating to the dating of astronomical features. For example, based upon this emerging science, the Galactic thin disk of the Milky Way galaxy is estimated to have been formed 8.3 ± 1.8 billion years ago.[148]

Nuclear physics

Creationists point to experiments they have performed, which they claim demonstrate that 1.5 billion years of nuclear decay took place over a short period, from which they infer that "billion-fold speed-ups of nuclear decay" have occurred, a massive violation of the principle that radioisotope decay rates are constant, a core principle underlying nuclear physics generally, and radiometric dating in particular.[149]

The scientific community points to numerous flaws in these experiments, to the fact that their results have not been accepted for publication by any peer-reviewed scientific journal, and to the fact that the creationist scientists conducting them were untrained in experimental geochronology.[150][151]

In refutation of young Earth claims of inconstant decay-rates affecting the reliability of radiometric dating, Roger C. Wiens, a physicist specialising in isotope dating states:

There are only three quite technical instances where a half-life changes, and these do not affect the dating methods [under discussion]":[152]

- Only one technical exception occurs under terrestrial conditions, and this is not for an isotope used for dating.... The artificially-produced isotope, beryllium-7 has been shown to change by up to 1.5%, depending on its chemical environment. ... [H]eavier atoms are even less subject to these minute changes, so the dates of rocks made by electron-capture decays would only be off by at most a few hundredths of a percent.

- ... Another case is material inside of stars, which is in a plasma state where electrons are not bound to atoms. In the extremely hot stellar environment, a completely different kind of decay can occur. 'Bound-state beta decay' occurs when the nucleus emits an electron into a bound electronic state close to the nucleus.... All normal matter, such as everything on Earth, the Moon, meteorites, etc. has electrons in normal positions, so these instances never apply to rocks, or anything colder than several hundred thousand degrees....

- The last case also involves very fast-moving matter. It has been demonstrated by atomic clocks in very fast spacecraft. These atomic clocks slow down very slightly (only a second or so per year) as predicted by Einstein's theory of relativity. No rocks in our solar system are going fast enough to make a noticeable change in their dates....

— Roger C. Wiens, Radiometric Dating, A Christian Perspective[153]

Misrepresentations of science

The Discovery Institute has a "formal declaration" titled A Scientific Dissent From Darwinism which has many evangelicals, people from fields irrelevant to biology and geology and few biologists. Many of the biologists who signed have fields not directly related to evolution.[154] Some of the biologists signed were deceived into signing the "declaration." In response, there is Project Steve.

Quote mining

As a means to criticise mainstream science, creationists have been known to quote, at length, scientists who ostensibly support the mainstream theories, but appear to acknowledge criticisms similar to those of creationists.[62] Almost universally these have been shown to be quote mines that do not accurately reflect the evidence for evolution or the mainstream scientific community's opinion of it, or highly out-of-date.[155][156] Many of the same quotes used by creationists have appeared so frequently in Internet discussions due to the availability of cut and paste functions, that the TalkOrigins Archive has created "The Quote Mine Project" for quick reference to the original context of these quotations.[155] Creationists often quote mine Darwin, especially with regard to the seeming improbability of the evolution of the eye, to give support to their views.[157]

The Panda's Thumb blog has some material on quote mining.[158]

Public policy issues

The creation–evolution controversy has grown in importance in recent years, particularly as a result of the Southern strategy of the Republican Party strategist Kevin Phillips, during the Nixon and Reagan administrations in the U.S. He saw that the African-American Civil Rights Movement had alienated many poor white southern voters of the Bible Belt and set out to capture this electorate through an alliance with the "New Right" Christian right movement.[159]

Science education

Creationists promoted the idea that evolution is a theory in crisis[2][80] with scientists criticizing evolution[160] and claim that fairness and equal time requires educating students about the alleged scientific controversy.

Opponents, being the overwhelming majority of the scientific community and science education organizations,[161] reply that there is no scientific controversy and that the controversy exists solely in terms of religion and politics.[2][160]

George Mason University Biology Department introduced a course on the creation/evolution controversy, and apparently as students learn more about biology, they find objections to evolution less convincing, suggesting that "teaching the controversy" rightly as a separate elective course on philosophy or history of science, or "politics of science and religion," would undermine creationists' criticisms, and that the scientific community's resistance to this approach was bad public relations.[162]

Freedom of speech

Creationists have claimed that preventing them from teaching creationism violates their right of freedom of speech. Court cases (such as Webster v. New Lenox School District (1990) and Bishop v. Aronov (1991)) have upheld school districts' and universities' right to restrict teaching to a specified curriculum.

Issues relating to religion

Religion and historical scientists

Creationists often argue that Christianity and literal belief in the Bible are either foundationally significant or directly responsible for scientific progress.[163] To that end, Institute for Creation Research founder Henry M. Morris has enumerated scientists such as astronomer and philosopher Galileo Galilei, mathematician and theoretical physicist James Clerk Maxwell, mathematician and philosopher Blaise Pascal, geneticist monk Gregor Mendel, and Isaac Newton as believers in a biblical creation narrative.[164]

This argument usually involves scientists who were no longer alive when evolution was proposed or whose field of study did not include evolution. The argument is generally rejected as specious by those who oppose creationism.[165]

Many of the scientists in question did some early work on the mechanisms of evolution, e.g., the modern evolutionary synthesis combines Darwin's theory of evolution with Mendel's theories of inheritance and genetics. Though biological evolution of some sort had become the primary mode of discussing speciation within science by the late-19th century, it was not until the mid-20th century that evolutionary theories stabilized into the modern synthesis. Geneticist and evolutionary biologist Theodosius Dobzhansky, called the Father of the Modern Synthesis, argued that "Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution," and saw no conflict between evolutionary and his religious beliefs.[166] Nevertheless, some of the historical scientists marshalled by creationists were dealing with quite different issues than any are engaged with today: Louis Pasteur, for example, opposed the theory of spontaneous generation with biogenesis, an advocacy some creationists describe as a critique on chemical evolution and abiogenesis. Pasteur accepted that some form of evolution had occurred and that the Earth was millions of years old.[167]

The Relationship between religion and science was not portrayed in antagonistic terms until the late-19th century, and even then there have been many examples of the two being reconcilable for evolutionary scientists.[168] Many historical scientists wrote books explaining how pursuit of science was seen by them as fulfillment of spiritual duty in line with their religious beliefs. Even so, such professions of faith were not insurance against dogmatic opposition by certain religious people.

Forums

Debates

Many creationists and scientists engage in frequent public debates regarding the origin of human life, hosted by a variety of institutions. However, some scientists disagree with this tactic, arguing that by openly debating supporters of supernatural origin explanations (creationism and intelligent design), scientists are lending credibility and unwarranted publicity to creationists, which could foster an inaccurate public perception and obscure the factual merits of the debate.[169] For example, in May 2004 Dr. Michael Shermer debated creationist Kent Hovind in front of a predominantly creationist audience. In Shermer's online reflection while he was explaining that he won the debate with intellectual and scientific evidence he felt it was "not an intellectual exercise," but rather it was "an emotional drama," with scientists arguing from "an impregnable fortress of evidence that converges to an unmistakable conclusion," while for creationists it is "a spiritual war."[170] While receiving positive responses from creationist observers, Shermer concluded "Unless there is a subject that is truly debatable (evolution v. creation is not), with a format that is fair, in a forum that is balanced, it only serves to belittle both the magisterium of science and the magisterium of religion."[170] (see Non-overlapping magisteria). Others, like evolutionary biologist Massimo Pigliucci, have debated Hovind, and have expressed surprise to hear Hovind try "to convince the audience that evolutionists believe humans came from rocks" and at Hovind's assertion that biologists believe humans "evolved from bananas."[171]

In September 2012, educator and television personality Bill Nye of Bill Nye the Science Guy fame spoke with the Associated Press and aired his fears about acceptance of creationist theory, believing that teaching children that creationism is the only true answer and without letting them understand the way science works will prevent any future innovation in the world of science.[172][173] In February 2014, Nye defended evolution in the classroom in a debate with creationist Ken Ham on the topic of whether creation is a viable model of origins in today's modern, scientific era.[174][175][176]

Eugenie Scott of the National Center for Science Education, a nonprofit organization dedicated to defending the teaching of evolution in the public schools, claimed debates are not the sort of arena to promote science to creationists.[170] Scott says that "Evolution is not on trial in the world of science," and "the topic of the discussion should not be the scientific legitimacy of evolution" but rather should be on the lack of evidence in creationism. Stephen Jay Gould adopted a similar position, explaining:

Debate is an art form. It is about the winning of arguments. It is not about the discovery of truth. There are certain rules and procedures to debate that really have nothing to do with establishing fact—which [creationists] are very good at. Some of those rules are: never say anything positive about your own position because it can be attacked, but chip away at what appear to be the weaknesses in your opponent's position. They are good at that. I don't think I could beat the creationists at debate. I can tie them. But in courtrooms they are terrible, because in courtrooms you cannot give speeches. In a courtroom you have to answer direct questions about the positive status of your belief.— Stephen Jay Gould, lecture 1985[177]

Political lobbying

On both sides of the controversy a wide range of organizations are involved at a number of levels in lobbying in an attempt to influence political decisions relating to the teaching of evolution. These include the Discovery Institute, the National Center for Science Education, the National Science Teachers Association, state Citizens Alliances for Science, and numerous national science associations and state academies of science.[178]

Media coverage

The controversy has been discussed in numerous newspaper articles, reports, op-eds and letters to the editor, as well as a number of radio and television programmes (including the PBS series, Evolution (2001) and Coral Ridge Ministries' Darwin's Deadly Legacy (2006)). This has led some commentators to express a concern at what they see as a highly inaccurate and biased understanding of evolution among the general public. Edward Humes states:

There are really two theories of evolution. There is the genuine scientific theory and there is the talk-radio pretend version, designed not to enlighten but to deceive and enrage.The talk-radio version had a packed town hall up in arms at the Why Evolution Is Stupid lecture. In this version of the theory, scientists supposedly believe that all life is accidental, a random crash of molecules that magically produced flowers, horses and humans – a scenario as unlikely as a tornado in a junkyard assembling a 747. Humans come from monkeys in this theory, just popping into existence one day. The evidence against Darwin is overwhelming, the purveyors of talk-radio evolution rail, yet scientists embrace his ideas because they want to promote atheism.

— Edward Humes, Unintelligent Designs on Darwin[179]

Outside the United States

While the controversy has been prominent in the United States, it has flared up in other countries as well.[182][183][184]

Europe

Europeans have often regarded the creation–evolution controversy as an American matter.[183] In recent years the conflict has become an issue in other countries including Germany, the United Kingdom, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Turkey and Serbia.[183][184][185][186][187]

On September 17, 2007, the Committee on Culture, Science and Education of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) issued a report on the attempt by American-inspired creationists to promote creationism in European schools. It concludes "If we are not careful, creationism could become a threat to human rights which are a key concern of the Council of Europe... The war on the theory of evolution and on its proponents most often originates in forms of religious extremism which are closely allied to extreme right-wing political movements... some advocates of strict creationism are out to replace democracy by theocracy."[188] The Council of Europe firmly rejected creationism.[189]

Australia

Under the former Queensland state government of Joh Bjelke-Petersen, in the 1980s Queensland allowed the teaching of creationism in secondary schools.[190] In 2010, the Queensland state government introduced the topic of creationism into school classes within the "ancient history" subject where its origins and nature are discussed as a significant controversy.[191] Public lectures have been given in rented rooms at universities, by visiting American speakers.[192] One of the most acrimonious aspects of the Australian debate was featured on the science television program Quantum, about a long-running and ultimately unsuccessful court case by Ian Plimer, Professor of Geology at the University of Melbourne, against an ordained minister, Dr. Allen Roberts, who had claimed that there were remnants of Noah's Ark in eastern Turkey. Although the court found that Roberts had made false and misleading claims, they were not made in the course of trade or commerce, so the case failed.[193]

Islamic countries

In recent times, the controversy has become more prominent in Islamic countries.[194] In Egypt, evolution is currently taught in schools, but Saudi Arabia and Sudan have both banned the teaching of evolution in schools.[182][18] Creation science has also been heavily promoted in Turkey and in immigrant communities in Western Europe, primarily by Harun Yahya.[184] In Iran, traditional practice of Shia Islam isn't preoccupied with Qur'anic literalism as in case of Saudi Wahhabism but ijtihad, many influential Iranian Shi'ite scholars, including several who were closely involved in Iranian Revolution, are not opposed to evolutionary ideas in general, disagreeing that evolution necessarily conflicts with the Muslim mainstream.[18] Iranian pupils since 5th grade of elementary school learn only about evolution, thus portraying geologists and scientists in general as an authoritative voices of scientific knowledge.[18]

See also

- Anti-intellectualism

- Clergy Letter Project

- Creation and evolution in public education

- Evolutionary origin of religions

- Hindu views on evolution

- History of the creation–evolution controversy

- Jainism and non-creationism

- Jewish views on evolution

- Mormon views on evolution

- Objections to evolution

- Project Steve

- Relationship between religion and science

- Stereotypes of Americans

- TalkOrigins

- Teach the Controversy

- Theology of creationism and evolution

References

- 1 2 IAP Member Academies (June 21, 2006). "IAP Statement on the Teaching of Evolution". IAP. Trieste, Italy: The World Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 2014-08-27.

- 1 2 3 4 "Statement on the Teaching of Evolution" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: American Association for the Advancement of Science. February 16, 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-02-21. Retrieved 2014-07-31.

Some bills seek to discredit evolution by emphasizing so-called 'flaws' in the theory of evolution or 'disagreements' within the scientific community. Others insist that teachers have absolute freedom within their classrooms and cannot be disciplined for teaching non-scientific 'alternatives' to evolution. A number of bills require that students be taught to 'critically analyze' evolution or to understand 'the controversy.' But there is no significant controversy within the scientific community about the validity of the theory of evolution. The current controversy surrounding the teaching of evolution is not a scientific one.

- ↑ Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District, 04 cv 2688 (M.D. Pa. December 20, 2005). Whether ID Is Science, p. 83.

- 1 2 Larson 2004, p. 258: "Virtually no secular scientists accepted the doctrines of creation science; but that did not deter creation scientists from advancing scientific arguments for their position."

- ↑ Skoog, Gerald (2007). "An NSTA Evolution Q&A". National Science Teachers Association. Arlington, VA: National Science Teachers Association. Retrieved 2014-08-27.

- ↑ Numbers 1992, pp. 3–240

- ↑ Montgomery, David R. (November 2012). "The evolution of creationism" (PDF). GSA Today (Geological Society of America) 22 (11): 4–9. doi:10.1130/GSATG158A.1. Retrieved 2016-01-28.

- 1 2 Peters, Ted; Hewlett, Martinez (December 22, 2005). "The Evolution Controversy: Who's Fighting with Whom about What?" (PDF). Pacific Lutheran Theological Seminary. Berkeley, CA: Pacific Lutheran Theological Seminary. Evolution Brief E2. Retrieved 2014-08-27.

- ↑ Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District, 04 cv 2688 (M.D. Pa. December 20, 2005). Context, p. 20.

- ↑ Slevin, Peter (March 14, 2005). "Battle on Teaching Evolution Sharpens". The Washington Post. p. A01. Retrieved 2014-08-27.

- ↑ Renka, Russell D. (November 16, 2005). "The Political Design of Intelligent Design". Renka's Home Page. Round Rock, TX. Retrieved 2014-08-27.

- ↑ Wilgoren, Jodi (August 21, 2005). "Politicized Scholars Put Evolution on the Defensive". The New York Times. Retrieved 2014-08-27.

- ↑ Forrest, Barbara (April 2002). "The Newest Evolution of Creationism". Natural History (Research Triangle Park, NC: Natural History Magazine, Inc.) 111 (3): 80. ISSN 0028-0712. Retrieved 2014-06-06.

- ↑ Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District, 04 cv 2688 (M.D. Pa. December 20, 2005). Introduction, pp. 7–9, also Whether ID Is Science, pp. 64–89, and Promoting Religion, p. 90.

- ↑ Curry, Andrew (February 27, 2009). "Creationist Beliefs Persist in Europe". Science (Washington, D.C.: American Association for the Advancement of Science) 323 (5918): 1159. doi:10.1126/science.323.5918.1159. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 19251601.

News coverage of the creationism-versus-evolution debate tends to focus on the United States ... But in the past 5 years, political clashes over the issue have also occurred in countries all across Europe. ... 'This isn't just an American problem,' says Dittmar Graf of the Technical University of Dortmund, who organized the meeting.

- ↑ Larson 2004, pp. 247–263, Chapter 11: "Modern Culture Wars"

- Ruse 1999, p. 26: "One thing that historians delighted in showing is that, contrary to the usually held tale of science and religion being always opposed [Conflict thesis] ... religion and theologically inclined philosophy have frequently been very significant factors in the forward movement of science."

- ↑ Cantor, Geoffrey and Marc Swetlitz, (editors). Jewish Tradition and the Challenge of Darwinism. University of Chicago Press. 2006. ISBN 978-0-226-09276-8

- 1 2 3 4 Burton, Elise K. (May–June 2010). "Teaching Evolution in Muslim States:Iran and Saudi Arabia Compared". Reports of the National Center for Science Education (Berkeley, CA: National Center for Science Education) 30 (3): 25–29. ISSN 2158-818X. Retrieved 2014-01-13.

- ↑ McKenna, Josephine (October 28, 2014). "Pope says evolution, Big Bang are real". USA Today (Tysons Corner, VA: Gannett Company). Religion News Service. Retrieved 2016-01-28.

- ↑ Gordon, Kara (October 30, 2014). "The Pope's Views on Evolution Haven't Really Evolved". The Atlantic (Washington, D.C.: Atlantic Media). ISSN 1072-7825. Retrieved 2016-01-28.