Lucas Cranach the Elder

| Lucas Cranach the Elder | |

|---|---|

Lucas Cranach the Younger, Portrait at age 77 (oil on panel, 67 × 49 cm), Florence, IT: Uffizi Gallery, c. 1550. | |

| Born |

Lucas Maler c. 1472 Kronach |

| Died |

16 October 1553 (aged 81) Weimar |

| Known for | Painting |

| Movement | German Renaissance |

| Patron(s) | The Electors of Saxony |

Lucas Cranach the Elder (Lucas Cranach der Ältere, c. 1472 – 16 October 1553) was a German Renaissance painter and printmaker in woodcut and engraving. He was court painter to the Electors of Saxony for most of his career, and is known for his portraits, both of German princes and those of the leaders of the Protestant Reformation, whose cause he embraced with enthusiasm, becoming a close friend of Martin Luther. He also painted religious subjects, first in the Catholic tradition, and later trying to find new ways of conveying Lutheran religious concerns in art. He continued throughout his career to paint nude subjects drawn from mythology and religion. He had a large workshop and many works exist in different versions; his son Lucas Cranach the Younger, and others, continued to create versions of his father's works for decades after his death. Lucas Cranach the Elder has been considered the most successful German artist of his time.[1]

Early life

He was born at Kronach in upper Franconia, probably in 1472. His exact date of birth is unknown. He learned the art of drawing from his father Hans Maler (his surname meaning "painter" and denoting his profession, not his ancestry, after the manner of the time and class).[2] His mother, with surname Hübner, died in 1491. Later, the name of his birthplace was used for his surname, another custom of the times. How Cranach was trained is not known, but it was probably with local south German masters, as with his contemporary Matthias Grünewald, who worked at Bamberg and Aschaffenburg (Bamberg is the capital of the diocese in which Kronach lies). There are also suggestions that Cranach spent some time in Vienna around 1500.[2]

According to Gunderam (the tutor of Cranach's children) Cranach demonstrated his talents as a painter before the close of the 15th century. His work then drew the attention of Duke Friedrich III, Elector of Saxony, known as Frederick the Wise, who attached Cranach to his court in 1504. The records of Wittenberg confirm Gunderam's statement to this extent that Cranach's name appears for the first time in the public accounts on the 24 June 1504, when he drew 50 gulden for the salary of half a year, as pictor ducalis ("the duke's painter"). Cranach was to remain in the service of the Elector and his successors for the rest of his life, although he was able to undertake other work.[2]

Cranach married Barbara Brengbier, the daughter of a burgher of Gotha and also born there; she died at Wittenberg on 26 December 1540. Cranach later owned a house at Gotha, but most likely he got to know Barbara near Wittenberg, where her family also owned a house, that later also belonged to Cranach.[2]

Career

The first evidence of Cranach's skill as an artist comes in a picture dated 1504. Early in his career he was active in several branches of his profession: sometimes a decorative painter, more frequently producing portraits and altarpieces, woodcuts, engravings, and designing the coins for the electorate.

Early in the days of his official employment he startled his master's courtiers by the realism with which he painted still life, game and antlers on the walls of the country palaces at Coburg and Locha; his pictures of deer and wild boar were considered striking, and the duke fostered his passion for this form of art by taking him out to the hunting field, where he sketched "his grace" running the stag, or Duke John sticking a boar.

Before 1508 he had painted several altar-pieces for the Castle Church at Wittenberg in competition with Albrecht Dürer, Hans Burgkmair and others; the duke and his brother John were portrayed in various attitudes and a number of his best woodcuts and copper-plates were published.

In 1509 Cranach went to the Netherlands, and painted the Emperor Maximilian and the boy who afterwards became Emperor Charles V. Until 1508 Cranach signed his works with his initials. In that year the elector gave him the winged snake as an emblem, or Kleinod, which superseded the initials on his pictures after that date.

Cranach was the court painter to the electors of Saxony in Wittenberg, an area in the heart of the emerging Protestant faith. His patrons were powerful supporters of Martin Luther, and Cranach used his art as a symbol of the new faith. Cranach made numerous portraits of Luther, and provided woodcut illustrations for Luther's German translation of the Bible.[3] Somewhat later the duke conferred on him the monopoly of the sale of medicines at Wittenberg, and a printer's patent with exclusive privileges as to copyright in Bibles. Cranach's presses were used by Martin Luther. His apothecary shop was open for centuries, and was only lost by fire in 1871.

Cranach, like his patron, was friendly with the Protestant Reformers at a very early stage; yet it is difficult to fix the time of his first meeting with Martin Luther. The oldest reference to Cranach in Luther's correspondence dates from 1520. In a letter written from Worms in 1521, Luther calls him his "gossip", warmly alluding to his "Gevatterin", the artist's wife. Cranach first made an engraving of Luther in 1520, when Luther was an Augustinian friar; five years later, Luther renounced his religious vows, and Cranach was present as a witness at the betrothal festival of Luther and Katharina von Bora.[2] He was also godfather to their first child, Johannes "Hans" Luther, born 1526. In 1530 Luther lived at the citadel of Veste Coburg under the protection of the Duke of Saxe-Coburg and his room is preserved there along with a painting of him. The Dukes became noted collectors of Cranach's work, some of which remains in the family collection at Callenberg Castle.

The death in 1525 of the Elector Frederick the Wise and Elector John's in 1532 brought no change in Cranach's position; he remained a favourite with John Frederick I, under whom he twice (1531 and 1540) filled the office of burgomaster of Wittenberg.

In 1547, John Frederick was taken prisoner at the Battle of Mühlberg, and Wittenberg was besieged. As Cranach wrote from his house to the grand-master Albert, Duke of Prussia at Königsberg to tell him of John Frederick's capture, he showed his attachment by saying,

I cannot conceal from your Grace that we have been robbed of our dear prince, who from his youth upwards has been a true prince to us, but God will help him out of prison, for the Kaiser is bold enough to revive the Papacy, which God will certainly not allow.

During the siege Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, remembered Cranach from his childhood and summoned him to his camp at Pistritz. Cranach came, and begged on his knees for kind treatment for Elector John Frederick.

Three years afterward, when all the dignitaries of the Empire met at Augsburg to receive commands from the emperor, and Titian came at Charles's bidding to paint King Philip II of Spain, John Frederick asked Cranach to visit the city; and here for a few months he stayed in the household of the captive elector, whom he afterward accompanied home in 1552.

He died at age 81 on October 16, 1553, at Weimar, where the house in which he lived still stands in the marketplace.[1]

Cranach had two sons, both artists: Hans Cranach, whose life is obscure and who died at Bologna in 1537; and Lucas Cranach the Younger, born in 1515, who died in 1586.[2] He also had three daughters. One of them was Barbara Cranach, who died in 1569, married Christian Brück (Pontanus), and was an ancestor of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

His granddaughter married Polykarp Leyser the Elder, thus making him an ancestor of the Polykarp Leyser family of theologians.

Veneration

The Lutheran Church remembers Cranach as a great Christian on April 6 along with Dürer,[4] and possibly Matthias Grünewald or Burgkmair.[5] The liturgical calendar of the Episcopal Church (USA) honors Cranach, Dürer and Grünewald on August 5.

Works and art

.jpg)

The oldest extant picture by Cranach is the Rest of the Virgin during the Flight into Egypt, of 1504. The painting already shows remarkable skill and grace, and the pine forest in the background shows a painter familiar with the mountain scenery of Thuringia. There is more forest gloom in landscapes of a later time.

Following the huge international success of Dürer's prints, other German artists, much more than Italian ones, devoted their talents to woodcuts and engravings. This accounts for the comparative unproductiveness as painters of Albrecht Dürer and Hans Holbein the Younger, and also may explain why Cranach was not especially skilled at handling colour, light, and shade. Constant attention to contour and to black and white, as an engraver, seems to have affected his sight; and he often outlined shapes in black rather than employing modelling and chiaroscuro.

The largest proportion of Cranach's output is of portraits, and it is chiefly thanks to him that we know what the German Reformers and their princely adherents looked like. He painted not only Martin Luther himself but also Luther's wife, mother and father. He also depicted leading Catholics like Albert of Brandenburg, archbishop elector of Mainz, Anthony Granvelle and the Duke of Alva.

A dozen likenesses of Frederick III and his brother John are dated 1532. It is characteristic of Cranach's prolific output, and a proof that he used a large workshop, that he received payment at Wittenberg in 1533 for "sixty pairs of portraits of the elector and his brother" on one day. Inevitably the quality of such works is variable.

Religious subjects

Cranach's religious subjects reflect the development of the Protestant Reformation, and its attitudes to religious images. In his early career, he painted several Madonnas; his first woodcut (1505) represents the Virgin and three saints in prayer before a crucifix. Later on he painted the marriage of St. Catherine, a series of martyrdoms, and scenes from the Passion.

After 1517 he occasionally illustrated the old subjects, but he also gave expression to some of the thoughts of the Reformers, although his portraits of reformers were more common than paintings of religious scenes. In a picture of 1518, where a dying man offers "his soul to God, his body to earth, and his worldly goods to his relations", the soul rises to meet the Trinity in heaven, and salvation is clearly shown to depend on faith and not on good works.

Other works of this period deal with sin and divine grace. One shows Adam sitting between John the Baptist and a prophet at the foot of a tree. To the left God produces the tables of the law, Adam and Eve partake of the forbidden fruit, the brazen serpent is reared aloft, and punishment supervenes in the shape of death and the realm of Satan. To the right, the Conception, Crucifixion and Resurrection symbolize redemption, and this is duly impressed on Adam by John the Baptist. There are two examples of this composition in the galleries of Gotha and Prague, both of them dated 1529.

Towards the end of his life, after Luther's initial hostility to large public religious images had softened, Cranach painted a number of "Lutheran altarpieces" of the Last Supper and other subjects, in which Christ was shown in a traditional manner, including a halo, but the apostles, without halos, were portraits of leading reformers. He also produced a number of violent anti-Catholic propaganda prints, in a cruder style, directed against the Papacy and the Catholic clergy. His best known work in this vein was a series of prints for the pamphlet Passional Christi und Antichristi, where scenes from the Passion of Christ were matched by a print mocking practices of the Catholic clergy, so that Christ driving the money-changers from the Temple was matched by the Pope, or Antichrist, signing indulgences over a table spread with cash (see gallery below).

One of his last works is the altarpiece, completed after his death by Lucas Cranach the Younger in 1555, for the Stadtkirche (city church) at Weimar. The iconography is original and unusual: Christ is shown twice, to the left trampling on Death and Satan, to the right crucified, with blood flowing from the lance wound. John the Baptist points to the suffering Christ, whilst the blood-stream falls on the head of a portrait of Cranach, and Luther reads from his book the words, "The blood of Christ cleanseth from all sin."

Mythological scenes

- Venus with Cupid stealing honey

-

Venus with Cupid stealing honey

-

_-_Cupid_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

Cupid, detail

Cranach was equally successful in somewhat naive mythological scenes, in which at least one slim female figure, naked except for a transparent drape, and perhaps for a large hat, nearly always features.

These are mostly in narrow upright formats; examples are several of Venus, alone or with Cupid, who has sometimes stolen a honeycomb, and complains to Venus that he has been stung by a bee (Weimar, 1530; Berlin, 1534). Diana with Apollo, shooting a bow, and Hercules sitting at the spinning-wheel mocked by Omphale and her maids are other such subjects. A similar approach was taken with the biblical subjects of Salome and Adam and Eve.

These subjects were produced early in his career, when they show Italian influences including that of Jacopo de' Barberi, who was at the court of Saxony for a period up to 1505. They then become rare until after the death of Frederick the Wise. The later nudes are in a distinctive style which abandons Italian influence for a revival of Late Gothic style, with small heads, narrow shoulders, high breasts and waists. The poses become more frankly seductive and even exhibitionist.[6]

Humour and pathos are combined at times with strong effect in pictures such as Jealousy (Augsburg, 1527; Vienna, 1530), where women and children are huddled into groups as they watch the strife of men wildly fighting around them. A lost canvas of 1545 is said to show hares catching and roasting hunters. In 1546, possibly under Italian influence, Cranach composed the Fons Juventutis ("Fountain of Youth"), executed by his son, a picture in which older women are seen entering a Renaissance fountain, and exiting it transformed into youthful beauties.

- Paintings

-

Portrait of a Saxon Prince (Possibly Johann, husband of Elizabeth of Hesse)

-

Portrait of a Saxon Princess (possibly George of Saxony's daughter-in-law Elizabeth of Hesse)

-

John Frederick I

-

.jpg)

Sybille of Cleves wife of John Frederick I

-

_-_Anna_Cuspinian.jpg)

Johannes Cuspinian's wife

-

Justice, 1537

-

Venus

-

Venus and Amor

-

.jpg)

Cupid complaining to Venus

-

A young man

-

Judith with the head of Holofernes

-

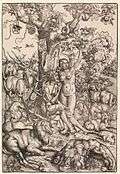

"Samson's Fight with the Lion", 1525

See also

References and sources

- References

- 1 2 The Jack and Belle Linsky Collection in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1984. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-87099370-1.

Lucas Cranach the Elder was perhaps the most successful German artist of his time.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "About Lucas Cranach". Cranach Digital Archive. Retrieved 25 January 2012.

- ↑ "Gallery Label for Crucifixion".

- ↑ "Commemorations". lcms.org.

- ↑ Lutheranism 101 edited by Scot A. Kinnaman, CPH, 2010

- ↑ Snyder, James (1985). Northern Renaissance Art. Harry N. Abrams. p. 383. ISBN 0-13-623596-4.

- Sources

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Cranach, Lucas". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Cranach, Lucas". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Further reading

- Luther, Martin (1521) Passional Christi und Antichristi Reprinted in W.H.T. Dau (1921) At the Tribunal of Caesar: Leaves from the Story of Luther's Life. St. Louis: Concordia. (Google Books)

- Posse, Hans (1942) Lucas Cranach d. ä. A. Schroll & Co., Vienna OCLC 773554 in German

- Descargues, Pierre (1960) Lucas Cranach the Elder (translated from the French by Helen Ramsbotham) Oldbourne Press, London, OCLC 434642

- Ruhmer, Eberhard (1963) Cranach (translated from the German by Joan Spencer) Phaidon, London, OCLC 1107030

- Friedländer, Max J.and Rosenberg, Jakob (1978) The Paintings of Lucas Cranach Tabard Press, New York ISBN 0-914427-31-8

- Schade, Werner (1980) Cranach, a Family of Master Painters (translated from the German by Helen Sebba) Putnam, New York, ISBN 0-399-11831-4

- Stepanov, Alexander (1997) Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1472–1553 Parkstone, Bournemouth, England, ISBN 1-85995-266-6

- Koerner, Joseph Leo (2004) The reformation of the image University of Chicago Press, Chicago, ISBN 0-226-45006-6

- Moser, Peter (2005) Lucas Cranach: His Life, His World, His Pictures (translated from the German by Kenneth Wynne) Babenberg Verlag, Bamberg, Germany, ISBN 3-933469-15-5

- Brinkmann, Bodo et al. (2007) Lucas Cranach Royal Academy of Arts, London, ISBN 1-905711-13-1

- Heydenreich, Gunnar (2007) Lucas Cranach the Elder: Painting materials, techniques and workshop practice, Amsterdam University Press, ISBN 978-90-5356-745-6

- Hyman, Timothy (April 16, 2008). "Cranach's golden age". TLS.

- O'Neill, J (1987). The Renaissance in the North. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

External links

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

-

Media related to Lucas Cranach d. Ä. at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Lucas Cranach d. Ä. at Wikimedia Commons - cranach.net Containing more than 15000 images and 6000 research documents, collaborative project by about 60 international art historians

- Cranach Digital Archive (cda) Containing images and research information, collaborative project by 26 international galleries

- Lucas Cranach the Elder at DMOZ

- Fifteenth- to eighteenth-century European paintings: France, Central Europe, the Netherlands, Spain, and Great Britain, a collection catalog fully available online as a PDF, which contains material on Lucas Cranach the Elder (cat. no. 9)

- Prints & People: A Social History of Printed Pictures, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Lucas Cranach the Elder (see index)

|