Crack cocaine

Crack cocaine is the freebase form of cocaine that can be smoked. It may also be termed rock, work, hard, iron, cavvy, base, but is most commonly known as just crack; the Manual of Adolescent Substance Abuse Treatment calls it the most addictive form of cocaine.[1] Crack rocks offer a short but intense high to smokers.[2] Crack first saw widespread use in primarily impoverished inner city neighborhoods in New York, Los Angeles, and Miami in late 1984 and 1985; the rapid increase in use and availability is referred to as the crack epidemic.[3]

Recreational use

Crack cocaine is commonly used as a recreational drug. Effects of crack cocaine include euphoria,[4] supreme confidence,[5] loss of appetite,[4] insomnia,[4] alertness,[4] increased energy,[4] a craving for more cocaine,[5] and potential paranoia (ending after use).[4][6] Its initial effect is to release a large amount of dopamine,[7] a brain chemical inducing feelings of euphoria. The high usually lasts from 5–10 minutes,[4][7] after which time dopamine levels in the brain plummet, leaving the user feeling depressed and low.[7] When (powder) cocaine is dissolved and injected, the absorption into the bloodstream is at least as rapid as the absorption of the drug which occurs when crack cocaine is smoked,[4] and similar euphoria may be experienced.

Adverse effects

Because crack is an illicit drug, users may consume impure or fake ("bunk") drug,[2] which may pose additional health risks.

Physiological effects

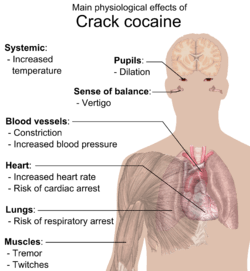

The short-term physiological effects of cocaine include[4] constricted blood vessels, dilated pupils, and increased temperature, heart rate, and blood pressure. Some users of cocaine report feelings of restlessness, irritability, and anxiety. In rare instances, sudden death can occur on the first use of cocaine or unexpectedly thereafter.[4] Cocaine-related deaths are often a result of cardiac arrest or seizures followed by respiratory arrest.

Like other forms of cocaine, smoking crack can increase heart rate[9] and blood pressure, leading to long-term cardiovascular problems. Some research suggests that smoking crack or freebase cocaine has additional health risks compared to other methods of taking cocaine. Many of these issues relate specifically to the release of methylecgonidine and its effect on the heart,[9] lungs,[10] and liver.[11]

- Toxic adulterants: Virtually any substance may have been added in order to expand the volume of a batch while still appearing to be pure crack. Occasionally, highly toxic substances are used, with an indefinite range of corresponding short and long-term health risks. For example, if candle wax or macadamia are procured alone or in combination with real crack, they will produce a noxious smoke when burned.

- Smoking problems: Any route of administration poses its own set of health risks; in the case of crack cocaine, smoking tends to be more harmful than other routes. Crack users tend to smoke the drug because that has a higher bioavailability than other routes typically used for drugs of abuse such as insufflation. Crack has a melting point of around 90 °C (194 °F),[1] and the smoke does not remain potent for long. Therefore, crack pipes are generally very short, to minimize the time between evaporating and ingestion (thereby minimizing loss of potency). Having a very hot pipe pressed against the lips often causes cracked and blistered lips, colloquially known as "crack lip". The use of "convenience store crack pipes"[12] - glass tubes which originally contained small artificial roses - may contribute to this condition. These 4-inch (10-cm) pipes[12] are not durable and will quickly develop breaks; users may continue to use the pipe even though it has been broken to a shorter length. The hot pipe might burn the lips, tongue, or fingers, especially when passed between people who take hits in rapid succession, causing the short pipe to reach higher temperatures than if used by one person alone.

- Pure or large doses: Because the quality of crack can vary greatly, some people might smoke larger amounts of diluted crack, unaware that a similar amount of a new batch of purer crack could cause an overdose. This can trigger heart problems or cause unconsciousness.

- Pathogens on pipes: When pipes are shared, bacteria or viruses can be transferred from person to person.

Crack lung

Crack lung is an acute injury to the lungs due to heavy use of smoked crack cocaine. Crack-cocaine smoke constricts blood vessels in the lungs and prevents oxygen and blood from circulating. Extreme crack-cocaine abuse results in scarring and permanent damage (i.e. crack lung). Crack lung is typically accompanied by a fever; other symptoms include cough, difficulty breathing and severe chest pain.

Radiographic imaging of the chest often shows hyperinflation, increased vascular markings, tree-in-bud sign, and the appearance of a "not quite normal chest radiograph". These findings are not specific to crack cocaine, but abuse can support a diagnosis.

Pregnancy and nursing

"Crack baby" is a term for a child born to a mother who used crack cocaine during her pregnancy. The threat that cocaine use during pregnancy poses to the fetus is now considered exaggerated.[13] Studies show that prenatal cocaine exposure (independent of other effects such as, for example, alcohol, tobacco, or physical environment) has no appreciable effect on childhood growth and development.[14] However, the official opinion of the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the United States warns about health risks while cautioning against stereotyping:

Many recall that "crack babies", or babies born to mothers who used crack cocaine while pregnant, were at one time written off by many as a lost generation. They were predicted to suffer from severe, irreversible damage, including reduced intelligence and social skills. It was later found that this was a gross exaggeration. However, the fact that most of these children appear normal should not be over-interpreted as indicating that there is no cause for concern. Using sophisticated technologies, scientists are now finding that exposure to cocaine during fetal development may lead to subtle, yet significant, later deficits in some children, including deficits in some aspects of cognitive performance, information-processing, and attention to tasks—abilities that are important for success in school.[15]

Some people previously believed that crack cocaine caused SIDS, but when investigators began looking at the incidence of SIDS in the children of women who used crack cocaine, they found it to be no higher than in children of women who smoked cigarettes.[16]

There are also warnings about the threat of breastfeeding: "It is likely that cocaine will reach the baby through breast milk." The March of Dimes advises the following regarding cocaine use during pregnancy:

Cocaine use during pregnancy can affect a pregnant woman and her unborn baby in many ways. During the early months of pregnancy, it may increase the risk of miscarriage. Later in pregnancy, it can trigger preterm labor (labor that occurs before 37 weeks of pregnancy) or cause the baby to grow poorly. As a result, cocaine-exposed babies are more likely than unexposed babies to be born with low birthweight (less than 5.5 lb or 2.5 kg). Low-birthweight babies are 20 times more likely to die in their first month of life than normal-weight babies, and face an increased risk of lifelong disabilities such as mental retardation and cerebral palsy. Cocaine-exposed babies also tend to have smaller heads, which generally reflect smaller brains. Some studies suggest that cocaine-exposed babies are at increased risk of birth defects, including urinary-tract defects and, possibly, heart defects. Cocaine also may cause an unborn baby to have a stroke, irreversible brain damage, or a heart attack.[17]

Psychological

Stimulant drug abuse (particularly amphetamine and cocaine) can lead to delusional parasitosis (aka Ekbom's Syndrome: a mistaken belief they are infested with parasites).[18] For example, excessive cocaine use can lead to formication, nicknamed "cocaine bugs" or "coke bugs", where the affected people believe they have, or feel, parasites crawling under their skin.[18] (Similar delusions may also be associated with high fever or in connection with alcohol withdrawal, sometimes accompanied by visual hallucinations of insects.)[18]

People experiencing these hallucinations might scratch themselves to the extent of serious skin damage and bleeding, especially when they are delirious.[6][18]

Tolerance

An appreciable tolerance to cocaine’s high may develop, with many addicts reporting that they seek but fail to achieve as much pleasure as they did from their first experience.[4] Some users will frequently increase their doses to intensify and prolong the euphoric effects. While tolerance to the high can occur, users might also become more sensitive (drug sensitization) to cocaine's local anesthetic (pain killing) and convulsant (seizure inducing) effects, without increasing the dose taken; this increased sensitivity may explain some deaths occurring after apparent low doses of cocaine.[4]

Addiction

Crack cocaine is popularly thought to be the most addictive form of cocaine.[1] However, this claim has been contested: Morgan and Zimmer wrote that available data indicated that "...smoking cocaine by itself does not increase markedly the likelihood of dependence.... The claim that cocaine is much more addictive when smoked must be reexamined."[19] They argued that cocaine users who are already prone to abuse are most likely to "move toward a more efficient mode of ingestion" (that is, smoking).

The intense desire to recapture the initial high is what is so addictive for many users.[7] On the other hand, Reinarman et al. wrote that the nature of crack addiction depends on the social context in which it is used and the psychological characteristics of users, pointing out that many heavy crack users can go for days or weeks without using the drugs.[20]

Overdose

A typical response among users is to have another hit of the drug; however, the levels of dopamine in the brain take a long time to replenish themselves, and each hit taken in rapid succession leads to progressively less intense highs.[7] However, a person might binge for 3 or more days without sleep, while inhaling hits from the pipe.[6]

Use of cocaine in a binge, during which the drug is taken repeatedly and at increasingly high doses, leads to a state of increasing irritability, restlessness, and paranoia.[4] This may result in a full-blown paranoid psychosis, in which the individual loses touch with reality and experiences auditory hallucinations.[4]

Large amounts of crack cocaine (several hundred milligrams or more) intensify the user's high, but may also lead to bizarre, erratic, and violent behavior.[4] Large amounts can induce tremors, vertigo, muscle twitches, paranoia, or, with repeated doses, a toxic reaction closely resembling amphetamine poisoning.[4]

Physical and chemical properties

In purer forms, crack rocks appear as off-white nuggets with jagged edges,[7] with a slightly higher density than candle wax. Purer forms of crack resemble a hard brittle plastic, in crystalline form[7] (snaps when broken). A crack rock acts as a local anesthetic (see: cocaine), numbing the tongue or mouth only where directly placed. Purer forms of crack will sink in water or melt at the edges when near a flame (crack vaporizes at 90 °C, 194 °F).[1]

Crack cocaine as sold on the streets may be adulterated or "cut" with other substances mimicking the appearance of crack cocaine to increase bulk. Use of toxic adulterants such as levamisole[21] has been documented.[2]

Synthesis

Sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3, common baking soda) is a base used in preparation of crack, although other weak bases may substitute for it. The net reaction when using sodium bicarbonate is

- Coc-H+Cl− + NaHCO3 → Coc + H2O + CO2 + NaCl

With Ammonium bicarbonate:

- Coc-H+Cl− + NH4HCO3 → Coc + NH4Cl + CO2 + H2O

With Ammonium carbonate:

- 2(Coc-H+Cl−) + (NH4)2CO3 → 2 Coc + 2 NH4Cl + CO2 + H2O

Crack cocaine is frequently purchased already in rock form,[7] although it is not uncommon for some users to "wash up" or "cook" powder cocaine into crack themselves. This process is frequently done with baking soda (sodium bicarbonate), water, and a spoon. Once mixed and heated, the bicarbonate breaks down into carbon dioxide and sodium carbonate, which then reacts with the hydrochloride of the powder cocaine, leaving cocaine as an oily free base. Once separated from the hydrochloride, the cocaine alkaloid floats to the top of the now leftover liquid. It is at this point that the oil is picked up rapidly, usually with a pin or long thin object. This pulls the oil up and spins it, allowing air to set and dry the oil, and allows the maker to roll the oil into the rock-like shape.

Crack vaporizes near temperature 90 °C (194 °F),[1] much lower than the cocaine hydrochloride melting point of 190 °C (374 °F).[1] Whereas cocaine hydrochloride cannot be smoked (burns with no effect),[1] crack cocaine when smoked allows for quick absorption into the blood stream, and reaches the brain in 8 seconds.[1] Crack cocaine can also be injected intravenously with the same effect as powder cocaine. However, whereas powder cocaine dissolves in water, crack must be dissolved in an acidic solution such as lemon juice or white vinegar, a process that effectively reverses the original conversion of powder cocaine to crack.

Society and culture

Legal status

_(7395870920).jpg)

Cocaine is listed as a Schedule I drug in the United Nations 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, making it illegal for non-state-sanctioned production, manufacture, export, import, distribution, trade, use and possession.[22][23]

Australia

In Australia, crack falls under the same category as cocaine, which is listed as a Schedule 8 controlled drug, indicating that any substances and preparations for therapeutic use under this category have high potential for abuse and addiction. It is permitted for some medical use, but is otherwise outlawed.

Canada

As a Schedule I substance under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, crack is not differentiated from cocaine and other coca products. However, the court may weigh the socio-economic factors of crack usage in sentencing. As a guideline, Schedule I drugs carry a maximum 7-year prison sentence for possession for an indictable offense and up to life imprisonment for trafficking and production. A summary conviction on possession carries a $1000–$2000 fine and/or 6 months to a year imprisonment.

United States

In the United States, cocaine is a Schedule II drug under the Controlled Substances Act, indicating that it has a high abuse potential but also carries a medicinal purpose.[24][25] Under the Controlled Substances Act, crack and cocaine are considered the same drug.

The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 increased penalties for crack cocaine possession and usage. It mandated a mandatory minimum sentence of five years without parole for possession of five grams of crack; to receive the same sentence with powder cocaine one had to have 500 grams.[26] This sentencing disparity was reduced from 100-to-1 to 18-to-1 by the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010.

Europe

In the United Kingdom, crack is a Class A drug under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971. In the Netherlands it is a List 1 drug of the Opium Law.

See also

- CIA and Contras cocaine trafficking in the US

- Cocaine paste ("paco")

- Crack epidemic

- Óxi, a similar drug made from cocaine paste

- Structurally related chemicals: proparacaine, tetracaine, lidocaine, procaine, hexylcaine, bupivacaine, benoxinate, mepivacaine, prilocaine, etidocaine, benzocaine, chloroprocaine, propoxycaine, dyclonine, dibucaine, and pramoxine.

- Substance abuse

- War on Drugs

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Manual of Adolescent Substance Abuse Treatment, Todd Wilk Estroff, M.D., 2001 (306 pages), pp. 44-45, (describes cocaine/crack processing & melting points): p.44 has "cannot be smoked because...melting point of 190°C"; p.45 has "It is the most addictive form of cocaine", webpage: , p. 44, at Google Books

- 1 2 3 Stacy O'Brien, Red Deer Advocate, December 2008, Officials warn of life-threatening cocaine in area.

- ↑ Reinarman, Craig; Levine, Harry G. (1997). "Crack in Context: America's Latest Demon Drug". In Reinarman, Craig; Levine, Harry G. Crack in America: Demon Drugs and Social Justice. Berkeley, CA.: University of California Press.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 "DEA, Drug Information, Cocaine", United States DOJ Drug Enforcement Administration, 2008, webpage: DEA-cocaine.

- 1 2 White Mischief: A Cultural History of Cocaine, Tim Madge, 2004, ISBN 1-56025-370-3, link: , p. 18, at Google Books.

- 1 2 3 "Life or Meth - CRACK OF THE 90'S", Salt Lake City Police Department, Utah, 2008, PDF file: Methlife-PDF.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 A.M. Costa Rica, July 2008, Crack rocks offer a short but intense high to smokers.

- ↑ Taylor, M.; Mackay, K.; Murphy, J.; McIntosh, A.; McIntosh, C.; Anderson, S.; Welch, K. (24 July 2012). "Quantifying the RR of harm to self and others from substance misuse: results from a survey of clinical experts across Scotland". BMJ Open 2 (4): e000774–e000774. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000774. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- 1 2 Scheidweiler KB, Plessinger MA, Shojaie J, Wood RW, Kwong TC (2003). "Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of methylecgonidine, a crack cocaine pyrolyzate". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 307 (3): 1179–87. doi:10.1124/jpet.103.055434. PMID 14561847. Retrieved 2008-02-24.

- ↑ Yang Y, Ke Q, Cai J, Xiao YF, Morgan JP (2001). "Evidence for cocaine and methylecgonidine stimulation of M(2) muscarinic receptors in cultured human embryonic lung cells". Br. J. Pharmacol. 132 (2): 451–60. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0703819. PMC 1572570. PMID 11159694. Retrieved 2008-02-24.

- ↑ Fandiño AS, Toennes SW, Kauert GF (2002). "Studies on hydrolytic and oxidative metabolic pathways of anhydroecgonine methyl ester (methylecgonidine) using microsomal preparations from rat organs". Chem. Res. Toxicol. 15 (12): 1543–8. doi:10.1021/tx0255828. PMID 12482236.

- 1 2 "A Rose With Another Name: Crack Pipe", Allan Lengel, The Washington Post, April 5, 2006, webpage: highbeam-576: states "four-inch-long tube that holds the flower" and "Convenience stores, liquor stores and gas stations...sell what the street calls 'rosebuds' or 'stems' for $1 to $2".

- ↑ Okie, Susan (2009-01-27). "The Epidemic That Wasn't". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Growth, Development, and Behavior in Early Childhood Following Prenatal Cocaine Exposure, Frank et al. 285 (12): 1613 — JAMA". Jama.ama-assn.org. 2001-03-28. Retrieved 2010-12-22.

- ↑ NIDA - Research Report Series - Cocaine Abuse and Addiction Archived September 26, 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Preventing Poisoned Minds", Dennis Meredith, Duke Magazine, July/August 2007, webpage: DM-17.

- ↑ "Street Drugs and pregnancy". March of Dimes. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- 1 2 3 4 "Delusional Parasitosis", The Bohart Museum of Entomology, 2005, webpage: UCDavis-delusional.

- ↑ Morgan, John P.; Zimmer, Lynn (1997). "Social Pharmacology of Smokeable Cocaine". In Reinarman, Craig; Levine, Harry G. Crack in America: Demon Drugs and Social Justice. Berkeley, Ca.: University of California Press.

- ↑ Reinarman, Craig; Waldorf, Dan; Murphy, Sheigla B.; Levine, Harry G. (1997). "The Contingent Call of the Pipe: Bingeing and Addiction Among Heavy Cocaine Smokers". In Reinarman, Craig; Levine, Harry G. Crack in America: Demon Drugs and Social Justice. Berkeley, Ca.: University of California Press.

- ↑ Kinzie, Erik (April 2009). "Levamisole Found in Patients Using Cocaine". Annals of Emergency Medicine 53 (4). Retrieved 2009-08-18.

- ↑ "Cocaine and Crack". European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. Retrieved 2008-05-01.

- ↑ "Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961" (PDF). International Narcotics Control Board. Retrieved 2008-05-01.

- ↑ "DEA, Title 21, Section 812". Usdoj.gov. Archived from the original on 2008-08-22. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

- ↑ Retrieved 2008-05-01.

- ↑ Sterling, Eric. "Drug Laws and Snitching: A Primer". PBS. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

Further reading

- Cooper, Edith Fairman, The emergence of crack cocaine abuse, Nova Publishers, 2002

External links

| Look up crack cocaine in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Crack cocaine. |