Cowboy Jimmy Moore

| Cowboy Jimmy Moore | |

|---|---|

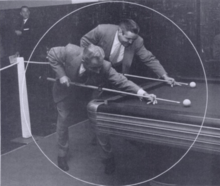

Willie Mosconi (left) and Jimmy Moore (right) at the 1953 World's Invitational[1] | |

| Born |

James William Moore September 14, 1910 Troup County, Georgia |

| Died |

November 17, 1999 (aged 89) Albuquerque, New Mexico |

Cowboy Jimmy Moore (September 14, 1910 – November 17, 1999), born James William Moore, was a world-class American pocket billiards (pool) player originally from Troup County, Georgia, and for most of his life a resident of Albuquerque, New Mexico, best known for his mastery in the game of straight pool (14.1 continuous).

An excellent athlete at various sports, Moore's many records in billiards include winning the Michigan State Billiard Championship four times, placing second at the World Championship five times competing against the best in the world such as Willie Mosconi, Irving Crane and Luther Lassiter, winning the United States National Pocket Billiards Championship in 1958, the National Invitation Pocket Billiards Championship in 1965 and the Legends of Pocket Billiards competition in 1984.

Moore was also known for his straight pool exhibition work, as a formidable road player, and for his unusual pool style, which included both his flamboyant cowboy dress, and his rare form of cueing technique known as a slip stroke. Moore also worked as a technical adviser for billiard-related scenes in television and film in such productions as My Living Doll, and the Jerry Lewis movie The Family Jewels. He is an inductee of the Billiard Congress of America's Hall of Fame, the International Pocket Billiards Hall of Fame, and the Albuquerque Sports Hall of Fame.

Early years

James William Moore was born on September 14, 1910[2] on a farm located in Troup County, Georgia, just outside the City of Hogansville. He was the son of a Georgia blacksmith, sheriff and streetcar conductor. He began working at a young age, supplementing his family's income variously as a cotton picker earning 35 cents per 100 pounds, managing a fruit stand, and delivering newspapers. His family moved to Detroit when he was 13, where other ways of making money presented themselves. Moore ran card games and pursued other games of chance, even pitching pennies. He was very good at such gambling pursuits and was a naturally gifted athlete, attaining a Triple-A level as a baseball player in the minor leagues, once bowled a perfect game, and was a fine golfer.[3][4][5]

I was shooting in the '70s soon after I took up golf. I thought about trying to become a pro but I figured there wasn't any money in it. That was true, back then. Same thing for baseball. I was a pretty good pitcher—I played in the minors for Belle Isle, out of Detroit—but I didn't think I could make a living at it.[3]— "Cowboy" Jimmy Moore, Billiards Digest (1999)

In 1928 at 18 years of age, Moore took a job as a pinsetter at Car Barns, a local bowling alley, earning six cents a line. True to form, Moore was a quick study, for a time carrying a 233 bowling average. Moore first picked up a cue stick at Car Barns, playing on the single 4 x 8 foot pool table the bowling alley had available. According to Moore he immediately fell in love with the game; specifically, with the game of straight pool (14.1 continuous), at which he would chiefly compete during his career, though not to the exclusion of all other billiard disciplines—Moore would become national snooker champion,[3][4][5] and would place second at the 1961 First Annual World's One-Pocket Billiards Tournament in Johnston City, Illinois.[6]

Straight pool was the game of championship pocket billiards competition until approximately the 1980s when it was overtaken by "faster" games such as nine-ball. In the game, a shooter may attempt to pocket any object ball on the table. The object is to reach a set number of points determined by agreement before the game—typically 150 in professional competition. One point is scored for each ball pocketed in the pocket called and where no foul has transpired.[7] According to Moore, his high run in the game was 236 ball in a row.[4]

Six months after his first introduction to the game, Moore entered and won the 1929 Michigan State billiard championship. He successfully defended that title in the following three years. During the midst of the Great Depression, however, playing pool for trophies was not a luxury Moore could afford, so he took his game on the road.[3][4]

On the road

Moore first partnered with hustler cum exhibition player, Ray St. Laurent, a colorful character who staged exhibitions wearing a red cape and mask while billed as "The Red Devil". Although St. Laurent fostered Moore, they were not equals on the pool table. One winter evening in Canton, Ohio, St. Laurent was losing badly in a thoroughly overmatched gambling session to Ohio road legend, Don Willis,[3] known as the "Cincinnati Kid", who was considered by many of his colleagues of the time "the deadliest player alive".[8] The wager was 25 cents a ball—a not inconsiderable sum at the time—and Moore was stakehorsing the match. Eventually disgusted by the uneven proceedings, Moore told St. Laurent that he couldn't win and asked him to step aside and let him have a go.[3] Willis later recalled:

Here was this punk kid sitting there saying, 'I'll play you some.' Well, he got out of that overcoat and ran over me in my home poolroom. He never missed a ball.[3]— Don Willis, Billiards Digest (1999)

Moore and Willis became traveling partners following their match, often accompanied on the road by future six-time world champion[9] Luther "Wimpy" Lassiter. Given his skill and prominent road partners, Moore's name began to be known in the billiard world. In 1940, the World Pocket Billiards (straight pool) titleholder of that year,[10] Andrew Ponzi, sought out Moore looking for a challenge. At the match ultimately arranged, Moore first beat Ponzi out of $80 playing nine-ball, and then beat him at his own game of choice, straight pool, with Moore scoring 125 points to Ponzi's 82.[3]

After Moore's match with Ponzi, he was hired by Ponzi's sometime employer, Sylvester Livingston, a pool impresario who hosted exhibitions with a stable of top pool talent including Irving Crane[3] who, like Lassiter, would become a six-time world champion.[11] During 1941 Moore performed 250 exhibitions across the country, earning $5 for matinees, and $7 for evening performances. He lost only one match over the year, and posted straight pool runs of 100 or more in 24 out of the 250 exhibitions.[3]

By that time Moore was recognizable by his cowboy airs.[3] He customarily wore cowboy boots, a white Stetson hat and a string tie, kept his hair in a crew-cut, and was rarely seen without a cigar.[1][12] He was also known for his unusual form of stroke. Moore employed a slip stroke[3]—a shooting technique in which a player releases his gripping hand briefly and re-grasps the cue farther back on the butt just before hitting the cue ball.[13] Employing the slip stroke to good effect, Moore was deadly accurate, but could also shoot with great power.[12][14]

In 1945, Moore's purchased a home in Albuquerque, New Mexico, where he would live for the rest of his life with his wife, Julie Chavez, whom he married in 1949. They had seven children together: sons Jamie, Raymond and Tommy, and daughters Pamela Nathan, Kolma Moore, Emily DiLorenzo and Linda Bates. Soon after moving to Albuquerque, he became co-owner and operator of the U Cue Billiards Hall located in the City.[4][5] It was said that hustlers avoided going through Albuquerque just to avoid getting into a money game with Moore.[14]

Exhibition and competition

Though Moore continued playing on the road—as he would for over 40 years—he began competing and placing in top-tier tournaments. His tournament career was to be overshadowed by an enduring series of runner-up finishes that would earn him the nickname "pool's underpaid prince" in such publications as Esquire Magazine. The name that stuck with him for life, however, was Cowboy. According to Moore, he became 'Cowboy' Jimmy Moore when he appeared at the Commodore Hotel championships in New York City in the 1950s wearing the required tuxedo, but nevertheless sporting cowboy boots and his signature white Stetson hat.[3][4]

The second-place-saga started in 1951 at the two-week-long, double-elimination, round robin format, World Championship tournament, held that year in Boston. At the competition, Moore was defeated in his last match by Willie Mosconi. His record was seven wins in nine matches, including triumphs over future Billiard Congress of America (BCA) Hall-of-Famers, Irving Crane and Arthur "Babe" Cranfield.[3][15]

In 1952 he made a strong showing in the same competition, held once more in Boston, running 93 balls against Lassiter, beating him 150 to 25, but again finishing behind Willie Mosconi, this time sharing second place with Jimmy Caras and Joe Procita.[16] Moore's match with Mosconi had an ending score of 150 to 58 in 19 innings.[3][15] Moore competed in the 1953 World Championship in San Francisco, but did not place, losing in his last match to Crane, 150-56 in 7 innings.[17]

The following year Moore took second place yet again in the World Championship, held that year in Philadelphia. The 1954 tournament was not sponsored and was unsanctioned by the BCA; in its absence being organized by Irving Crane. It was denominated by newspapers, such as The New York Times, as the "Unofficial World Pocket Billiard Championship." In a career highlight in the penultimate match there, Moore was losing 148 to 8 to Irving Crane. When Crane let him back to the table, Moore ran 142 balls and out. Despite this feat, Moore was dispatched to second place by Lassiter, with a final score of 150 to 95, sharing second place with Crane. The defending champion, Mosconi, did not participate.[3][18]

Moore's runner-up streak continued in the 1956 World Championship held at Judice's Academy in Brooklyn, New York. He clinched second place, to Willie Mosconi's now almost ubiquitous first, with a 150 to 50 score over Al Coslosky of Philadelphia in 15 innings, a win over Richard Riggie of Baltimore, 150 to 121, with an inspired run of 107 balls, but a loss to Lassiter, 150 to 70 in 7 innings.[19][20][21] That same year Moore played Mosconi at a challenge match in Kinston, North Carolina. It was not Moore's day as Mosconi posted a career highlight; a perfect match—150 balls in a row in one inning.[22]

In all, Moore came in second at the World Championship five times but never took the crown. He did however win the National Pocket Billiards Championship held in Chicago at Bensinger's Billiards in 1958. The tournament was a challenge match, marathon straight pool race to 3,000 points between Moore and Luther Lassiter. It was a tight competition, with Lassiter leading at one point 1,800 to 1,512. Moore battled back and eventually won with a final score of 3,000 to 2,634.[3][23]

He didn't think I could beat him, and that made me mad. I had to get mad to win. I was way behind, then I ran 95, 96, 97 and 175, and only missed then when I scratched on the break. Ran right past him.[3]— "Cowboy" Jimmy Moore, Billiards Digest (1999)

Moore would eventually have ten second place finishes in world-title competition. Nevertheless, he frequently competed with and beat all of the players whom he so often played second fiddle to in sanctioned tournament play. In fact, later in 1958, the same year he won the National Pocket Billiards Championship against Lassiter, he roundly defeated Mosconi in a two-day exhibition match in his home town of Albuquerque, with a final score of 500 to 397.[3] Moore and Mosconi would battle it out many times in unsanctioned but publicized play. In addition to matches previously mentioned, they vied at Albuquerque's old Chaplin Alley in 1956; at the Highland Bowl in 1958; and later, in matches in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, Philadelphia, Chicago and Johnston City at the Jansco Brother's Stardust Open, where Moore would win the prize for "all-around honors".[4]

It was not until 1965 at the National Invitation Pocket Billiards Championship, seven years after his last first place finish, that he would repeat as champion in a sanctioned tournament. At that contest held at the Riviera Terrace in New York City, along the way to first place and the prize of $4,000, Moore defeated: Onofrio Lauri 150 to 117; Joe Balsis 150 to -3; Cisero Murphy 150 to 96; "Champagne" Edwin Kelly 150 to 83 in 3 innings; and the ever-present Luther Lassiter, 150 to 41 in 4 innings. The runner up in the tourney was Joe Balsis.[24][25][26][27][28]

In addition to competition, Moore served as a technical adviser for billiard-related scenes in television and film, including My Living Doll starring Julie Newmar and Robert Cummings in 1964, and the Jerry Lewis movie The Family Jewels in 1965.[5]

Later life

Moore was inducted into the International Pocket Billiards Hall of Fame in 1982,[4] the Billiard Congress of America's Hall of Fame in 1994,[29] and the Albuquerque Sports Hall of Fame in 1998.[4] He remained competitive in tournament and match play well into his 70s.[3] In 1984, at age 74, Moore won the Legends of Pocket Billiards competition on ESPN.[30] Even in later years he was still deadly on a pool table, running 111 balls three days after his 80th birthday.[3] "Until the traffic accident I had about a year ago, I was still playing my usual speed" Moore said in July 1999 at the age of 89.[3] However, Moore's health declined rapidly that same year. He died on November 17, 1999 of natural causes.[4]

References

- 1 2 Steve Mizerak and Michael E. Panozzo (1990). Steve Mizerak's Complete Book of Pool. Chicago, Ill: Contemporary Books. p. 43. ISBN 0-8092-4255-9.

- ↑ MyFamily.com Inc. (1998-2007). U.S. Social Security death index search (exhibiting birth date). Retrieved on September 6, 2007

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 McCumber, David (July 1999). "Pool's Last Real Cowboy". Billiards Digest 21 (8): 60–64. ISSN 0164-761X.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Albuquerque Tribune (February 16, 1998). 'Cowboy' Jimmy Moore Beat the Best and All the Rest at Pool, by Carlos Salazar. Digitized version at AccessMyLibrary. Retrieved on January 20, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 Albuquerque Journal (November 18, 1999). Pool Legend Jimmy Moore Dies at Age 89, by Rick Wright. Digitized version at AccessMyLibrary. Retrieved on January 21, 2008.

- ↑ R. A. Dyer (2003). Hustler Days: Minnesota Fats, Wimpy Lassiter, Jersey Red, and America's Great Age of Pool. Guilford, Ct.: The Lyons Press. p. 229. ISBN 1-59228-646-1. OCLC 52822541.

- ↑ Shamos, Michael Ian (1993). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Billiards. New York, NY: Lyons & Burford. pp. 101–102. ISBN 1-55821-219-1.

- ↑ Gordon and Nancy Hart (March 1999). "The Greatest Show on Earth; Two of Johnston City Regulars Remember Action Pool's Years at the Showbar". Billiards Digest 21 (4): 41. ISSN 0164-761X.

- ↑ The New York Times Company October 27, 1988. Obituaries section: Luther Lassiter, 69, Billiards Star Who Captured Six World Titles (Associated Press). Retrieved on January 8, 2008.

- ↑ BCA Rules Committee (1970). Official Rule Book For All Pocket and Carom Billiard Games. Chicago, Illinois: Billiard Congress of America. p. 98. ISSN 1047-2444. OCLC 20759553.

- ↑ Billiards Digest (2000). A Rusty Game? Are today's players out of stroke when it comes to 14.1? by Bob Jewett. Billiards Digest Magazine. July 2000 issue, pages 22-24.

- 1 2 R. A. Dyer (2003). Hustler Days: Minnesota Fats, Wimpy Lassiter, Jersey Red, and America's Great Age of Pool. Guilford, Ct.: The Lyons Press. p. 126. ISBN 1-59228-646-1. OCLC 52822541.

- ↑ Robert Byrne (1990). Advanced Technique in Pool and Billiards. San Diego: Harcourt Trade Publishers. p. 37. ISBN 0-15-614971-0. OCLC 20759553.

- 1 2 Aylesworth, Ken "Sarge" (April 2005). "Cowboy Jimmy Moore Stroke Shot". On the Break News. Digitized version at OnTheBreakNews.com.

- 1 2 The New York Times Company (April 5, 1952). Mosconi Clinches Title; Beats Moore, 150-58, in Pocket Billiard Match at Boston. Retrieved on January 19, 2008.

- ↑ Unlike in a traditional tournament format, in a round robin competition, multiple players can tie for a particular placement.

- ↑ The New York Times Company (March 12, 1953). Mosconi Clinches Title; Defender Gains Eleventh World Cue Crown in 2 Innings. Retrieved on January 19, 2008.

- ↑ The New York Times Company (March 27, 1954). Lassiter Takes Title; Tops Crane to Capture Crown in Pocket Billiards. Retrieved on January 19, 2008.

- ↑ The New York Times Company (November 6, 1956). Moore Wins Cue Test, 150-50. Retrieved on January 19, 2008.

- ↑ The New York Times Company (November 17, 1956). Lassiter Defeats Moore. Retrieved on January 19, 2008.

- ↑ The New York Times Company (April 11, 1956). Mosconi Beats Rudolph; Eufemia, Moore Also Score in World Pocket Billiards. Retrieved on January 19, 2008.

- ↑ The New York Times Company (September 18, 1993). Willie Mosconi, 80, Who Ruled The World of Billiards With Style (obituary). Retrieved on March 25, 2008.

- ↑ The New York Times Company (April 2, 1958). Lassiter Adds to Cue Lead. Retrieved on January 19, 2008.

- ↑ The New York Times Company (November 1, 1965). Moore Gains Billiards Lead. Retrieved on January 19, 2008.

- ↑ The New York Times Company (November 3, 1965). Moore Wins and Holds Lead in U.S. Billiards Tournament. Retrieved on January 19, 2008.

- ↑ The New York Times Company (November 4, 1965). Moore Retains Cue Lead. Retrieved on January 19, 2008.

- ↑ The New York Times Company (November 5, 1965). Moore Holds Billiards Lead. Retrieved on January 19, 2008.

- ↑ The New York Times Company (November 6, 1965). Moore Wins Title, $4,000 In Pocket-Billiards Tourney. Retrieved on January 19, 2008.

- ↑ Billiard Congress America (1995-2005). BCA Hall of Fame Inductees: 1992 - 1996. Retrieved on September 6, 2007.

- ↑ Milwaukee Journal Sentinel (November 20, 1999). Jimmy Moore, Billiards champion. Digitized version at JSonline (fee required). Retrieved on January 20, 2008.