Functor

In mathematics, a functor is a type of mapping between categories which is applied in category theory. Functors can be thought of as homomorphisms between categories. In the category of small categories, functors can be thought of more generally as morphisms.

Functors were first considered in algebraic topology, where algebraic objects (like the fundamental group) are associated to topological spaces, and algebraic homomorphisms are associated to continuous maps. Nowadays, functors are used throughout modern mathematics to relate various categories. Thus, functors are generally applicable in areas within mathematics that category theory can make an abstraction of.

The word functor was borrowed by mathematicians from the philosopher Rudolf Carnap,[1] who used the term in a linguistic context:[2] see function word.

Definition

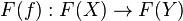

Let C and D be categories. A functor F from C to D is a mapping that[3]

- associates to each object

in C an object

in C an object  in D,

in D, - associates to each morphism

in C a morphism

in C a morphism  in D such that the following two conditions hold:

in D such that the following two conditions hold:

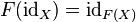

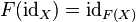

-

for every object

for every object  in C,

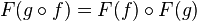

in C, -

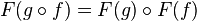

for all morphisms

for all morphisms  and

and  in C.

in C.

-

That is, functors must preserve identity morphisms and composition of morphisms.

Covariance and contravariance

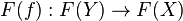

There are many constructions in mathematics that would be functors but for the fact that they "turn morphisms around" and "reverse composition". We then define a contravariant functor F from C to D as a mapping that

- associates to each object

in C an object

in C an object  in D,

in D, - associates to each morphism

in C a morphism

in C a morphism  in D such that

in D such that

for every object

for every object  in C,

in C, for all morphisms

for all morphisms  and

and  in C.

in C.

Note that contravariant functors reverse the direction of composition.

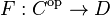

Ordinary functors are also called covariant functors in order to distinguish them from contravariant ones. Note that one can also define a contravariant functor as a covariant functor on the opposite category  .[4] Some authors prefer to write all expressions covariantly. That is, instead of saying

.[4] Some authors prefer to write all expressions covariantly. That is, instead of saying  is a contravariant functor, they simply write

is a contravariant functor, they simply write  (or sometimes

(or sometimes  ) and call it a functor.

) and call it a functor.

Contravariant functors are also occasionally called cofunctors.

Opposite functor

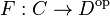

Every functor  induces the opposite functor

induces the opposite functor  , where

, where  and

and  are the opposite categories to

are the opposite categories to  and

and  .[5] By definition,

.[5] By definition,  maps objects and morphisms identically to

maps objects and morphisms identically to  . Since

. Since  does not coincide with

does not coincide with  as a category, and similarly for

as a category, and similarly for  ,

,  is distinguished from

is distinguished from  . For example, when composing

. For example, when composing  with

with  , one should use either

, one should use either  or

or  . Note that, following the property of opposite category,

. Note that, following the property of opposite category,  .

.

Bifunctors and multifunctors

A bifunctor (also known as a binary functor) is a functor whose domain is a product category. For example, the Hom functor is of the type Cop × C → Set. It can be seen as a functor in two arguments. The Hom functor is a natural example; it is contravariant in one argument, covariant in the other.

A multifunctor is a generalization of the functor concept to n variables. So, for example, a bifunctor is a multifunctor with n = 2.

Examples

Diagram: For categories C and J, a diagram of type J in C is a covariant functor  .

.

(Category theoretical) presheaf: For categories C and J, a J-presheaf on C is a contravariant functor  .

.

Presheaves: If X is a topological space, then the open sets in X form a partially ordered set Open(X) under inclusion. Like every partially ordered set, Open(X) forms a small category by adding a single arrow U → V if and only if  . Contravariant functors on Open(X) are called presheaves on X. For instance, by assigning to every open set U the associative algebra of real-valued continuous functions on U, one obtains a presheaf of algebras on X.

. Contravariant functors on Open(X) are called presheaves on X. For instance, by assigning to every open set U the associative algebra of real-valued continuous functions on U, one obtains a presheaf of algebras on X.

Constant functor: The functor C → D which maps every object of C to a fixed object X in D and every morphism in C to the identity morphism on X. Such a functor is called a constant or selection functor.

Endofunctor: A functor that maps a category to itself.

Identity functor: in category C, written 1C or idC, maps an object to itself and a morphism to itself. Identity functor is an endofunctor.

Diagonal functor: The diagonal functor is defined as the functor from D to the functor category DC which sends each object in D to the constant functor at that object.

Limit functor: For a fixed index category J, if every functor J→C has a limit (for instance if C is complete), then the limit functor CJ→C assigns to each functor its limit. The existence of this functor can be proved by realizing that it is the right-adjoint to the diagonal functor and invoking the Freyd adjoint functor theorem. This requires a suitable version of the axiom of choice. Similar remarks apply to the colimit functor (which is covariant).

Power sets: The power set functor P : Set → Set maps each set to its power set and each function  to the map which sends

to the map which sends  to its image

to its image  . One can also consider the contravariant power set functor which sends

. One can also consider the contravariant power set functor which sends  to the map which

sends

to the map which

sends  to its inverse image

to its inverse image

Dual vector space: The map which assigns to every vector space its dual space and to every linear map its dual or transpose is a contravariant functor from the category of all vector spaces over a fixed field to itself.

Fundamental group: Consider the category of pointed topological spaces, i.e. topological spaces with distinguished points. The objects are pairs (X, x0), where X is a topological space and x0 is a point in X. A morphism from (X, x0) to (Y, y0) is given by a continuous map f : X → Y with f(x0) = y0.

To every topological space X with distinguished point x0, one can define the fundamental group based at x0, denoted π1(X, x0). This is the group of homotopy classes of loops based at x0. If f : X → Y is a morphism of pointed spaces, then every loop in X with base point x0 can be composed with f to yield a loop in Y with base point y0. This operation is compatible with the homotopy equivalence relation and the composition of loops, and we get a group homomorphism from π(X, x0) to π(Y, y0). We thus obtain a functor from the category of pointed topological spaces to the category of groups.

In the category of topological spaces (without distinguished point), one considers homotopy classes of generic curves, but they cannot be composed unless they share an endpoint. Thus one has the fundamental groupoid instead of the fundamental group, and this construction is functorial.

Algebra of continuous functions: a contravariant functor from the category of topological spaces (with continuous maps as morphisms) to the category of real associative algebras is given by assigning to every topological space X the algebra C(X) of all real-valued continuous functions on that space. Every continuous map f : X → Y induces an algebra homomorphism C(f) : C(Y) → C(X) by the rule C(f)(φ) = φ o f for every φ in C(Y).

Tangent and cotangent bundles: The map which sends every differentiable manifold to its tangent bundle and every smooth map to its derivative is a covariant functor from the category of differentiable manifolds to the category of vector bundles.

Doing this constructions pointwise gives the tangent space, a covariant functor from the category of pointed differentiable manifolds to the category of real vector spaces. Likewise, cotangent space is a contravariant functor, essentially the composition of the tangent space with the dual space above.

Group actions/representations: Every group G can be considered as a category with a single object whose morphisms are the elements of G. A functor from G to Set is then nothing but a group action of G on a particular set, i.e. a G-set. Likewise, a functor from G to the category of vector spaces, VectK, is a linear representation of G. In general, a functor G → C can be considered as an "action" of G on an object in the category C. If C is a group, then this action is a group homomorphism.

Lie algebras: Assigning to every real (complex) Lie group its real (complex) Lie algebra defines a functor.

Tensor products: If C denotes the category of vector spaces over a fixed field, with linear maps as morphisms, then the tensor product  defines a functor C × C → C which is covariant in both arguments.[6]

defines a functor C × C → C which is covariant in both arguments.[6]

Forgetful functors: The functor U : Grp → Set which maps a group to its underlying set and a group homomorphism to its underlying function of sets is a functor.[7] Functors like these, which "forget" some structure, are termed forgetful functors. Another example is the functor Rng → Ab which maps a ring to its underlying additive abelian group. Morphisms in Rng (ring homomorphisms) become morphisms in Ab (abelian group homomorphisms).

Free functors: Going in the opposite direction of forgetful functors are free functors. The free functor F : Set → Grp sends every set X to the free group generated by X. Functions get mapped to group homomorphisms between free groups. Free constructions exist for many categories based on structured sets. See free object.

Homomorphism groups: To every pair A, B of abelian groups one can assign the abelian group Hom(A,B) consisting of all group homomorphisms from A to B. This is a functor which is contravariant in the first and covariant in the second argument, i.e. it is a functor Abop × Ab → Ab (where Ab denotes the category of abelian groups with group homomorphisms). If f : A1 → A2 and g : B1 → B2 are morphisms in Ab, then the group homomorphism Hom(f,g) : Hom(A2,B1) → Hom(A1,B2) is given by φ ↦ g ∘ φ ∘ f. See Hom functor.

Representable functors: We can generalize the previous example to any category C. To every pair X, Y of objects in C one can assign the set Hom(X,Y) of morphisms from X to Y. This defines a functor to Set which is contravariant in the first argument and covariant in the second, i.e. it is a functor Cop × C → Set. If f : X1 → X2 and g : Y1 → Y2 are morphisms in C, then the group homomorphism Hom(f,g) : Hom(X2,Y1) → Hom(X1,Y2) is given by φ ↦ g ∘ φ ∘ f.

Functors like these are called representable functors. An important goal in many settings is to determine whether a given functor is representable.

Properties

Two important consequences of the functor axioms are:

- F transforms each commutative diagram in C into a commutative diagram in D;

- if f is an isomorphism in C, then F(f) is an isomorphism in D.

One can compose functors, i.e. if F is a functor from A to B and G is a functor from B to C then one can form the composite functor G∘F from A to C. Composition of functors is associative where defined. Identity of composition of functors is identity functor. This shows that functors can be considered as morphisms in categories of categories, for example in the category of small categories.

A small category with a single object is the same thing as a monoid: the morphisms of a one-object category can be thought of as elements of the monoid, and composition in the category is thought of as the monoid operation. Functors between one-object categories correspond to monoid homomorphisms. So in a sense, functors between arbitrary categories are a kind of generalization of monoid homomorphisms to categories with more than one object.

Relation to other categorical concepts

Let  and

and  be categories. The collection of all functors

be categories. The collection of all functors  form the objects of a category: the functor category. Morphisms in this category are natural transformations between functors.

form the objects of a category: the functor category. Morphisms in this category are natural transformations between functors.

Functors are often defined by universal properties; examples are the tensor product, the direct sum and direct product of groups or vector spaces, construction of free groups and modules, direct and inverse limits. The concepts of limit and colimit generalize several of the above.

Universal constructions often give rise to pairs of adjoint functors.

Computer implementations

Functors sometimes appear in functional programming. For instance, the programming language Haskell has a class Functor where fmap is a polytypic function used to map functions (morphisms on Hask, the category of Haskell types) between existing types to functions between some new types.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Mac Lane, Saunders (1971), Categories for the Working Mathematician, Springer-Verlag: New York, p. 30, ISBN 978-3-540-90035-1

- ↑ Carnap, The Logical Syntax of Language, p. 13–14, 1937, Routledge & Kegan Paul

- ↑ Jacobson (2009), p. 19, def. 1.2.

- ↑ Jacobson (2009), p. 19–20.

- ↑ Mac Lane, Saunders; Moerdijk, Ieke (1992), Sheaves in geometry and logic: a first introduction to topos theory, Springer, ISBN 978-0-387-97710-2

- ↑ Hazewinkel, Michiel; Gubareni, Nadezhda Mikhaĭlovna; Gubareni, Nadiya; Kirichenko, Vladimir V. (2004), Algebras, rings and modules, Springer, ISBN 978-1-4020-2690-4

- ↑ Jacobson (2009), p. 20, ex. 2.

References

- Jacobson, Nathan (2009), Basic algebra 2 (2nd ed.), Dover, ISBN 978-0-486-47187-7.

External links

| Look up functor in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Functor", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

- see functor in nLab and the variations discussed and linked to there.

- André Joyal, CatLab, a wiki project dedicated to the exposition of categorical mathematics

- Hillman, Chris. "A Categorical Primer". CiteSeerX: 10

.1 : formal introduction to category theory..1 .24 .3264 - J. Adamek, H. Herrlich, G. Stecker, Abstract and Concrete Categories-The Joy of Cats

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: "Category Theory" — by Jean-Pierre Marquis. Extensive bibliography.

- List of academic conferences on category theory

- Baez, John, 1996,"The Tale of n-categories." An informal introduction to higher order categories.

- WildCats is a category theory package for Mathematica. Manipulation and visualization of objects, morphisms, categories, functors, natural transformations, universal properties.

- The catsters, a YouTube channel about category theory.

- Category Theory at PlanetMath.org.

- Video archive of recorded talks relevant to categories, logic and the foundations of physics.

- Interactive Web page which generates examples of categorical constructions in the category of finite sets.

| ||||||