Coulomb barrier

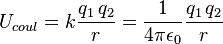

The Coulomb barrier, named after Coulomb's law, which is named after physicist Charles-Augustin de Coulomb (1736–1806), is the energy barrier due to electrostatic interaction that two nuclei need to overcome so they can get close enough to undergo a nuclear reaction. This energy barrier is given by the electrostatic potential energy:

where

- k is the Coulomb's constant = 8.9876×109 N m² C−2;

- ε0 is the permittivity of free space;

- q1, q2 are the charges of the interacting particles;

- r is the interaction radius.

A positive value of U is due to a repulsive force, so interacting particles are at higher energy levels as they get closer. A negative potential energy indicates a bound state (due to an attractive force).

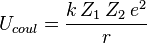

Coulomb's barrier increases with the atomic numbers (i.e. the number of protons) of the colliding nuclei:

where e is the elementary charge, 1.602 176 53×10−19 C, and Zi the corresponding atomic numbers.

To overcome this barrier, nuclei have to collide at high velocities, so their kinetic energies drive them close enough for the strong interaction to take place and bind them together.

According to the kinetic theory of gases, the temperature of a gas is just a measure of the average kinetic energy of the particles in that gas. For classical ideal gases the velocity distribution of the gas particles is given by Maxwell Boltzmann. From this distribution, the fraction of particles with a velocity, high enough to overcome the Coulomb's barrier, can be determined.

In practice, temperatures needed to overcome Coulomb's barrier turn out to be smaller than expected due to quantum-mechanical tunnelling, as established by Gamow. The consideration of barrier-penetration through tunnelling and the speed distribution gives rise to a limited range of conditions where the fusion can take place, known as the Gamow window.

It was the absence of a Coulomb barrier for the neutron that enabled James Chadwick to discover the neutron.[1][2]

See also

References

- ↑ Chadwick, James (1932). "Possible existence of a neutron". Nature 129 (3252): 312. doi:10.1038/129312a0.

- ↑ Chadwick, James (1932). "The existence of a neutron". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 136 (830): 692–708. doi:10.1098/rspa.1932.0112.