World tree

The world tree is a motif present in several religions and mythologies, particularly Indo-European religions, Siberian religions, and Native American religions. The world tree is represented as a colossal tree which supports the heavens, thereby connecting the heavens, the terrestrial world, and, through its roots, the underworld. It may also be strongly connected to the motif of the tree of life.

Specific world trees include világfa in Hungarian mythology, Ağaç Ana in Turkic mythology, Modun in Mongolian mythology, Yggdrasil (or Irminsul) in Germanic (including Norse) mythology, the Oak in Slavic and Finnish mythology, Kien-Mu or Jian-Mu in Chinese mythology, and in Hindu mythology the Ashvattha (a Sacred Fig).

Norse mythology

In Norse mythology, Yggdrasil is the world tree. Yggdrasil is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson. In both sources, Yggdrasil is an immense ash tree that is central and considered very holy. The Æsir go to Yggdrasil daily to hold their courts. The branches of Yggdrasil extend far into the heavens, and the tree is supported by three roots that extend far away into other locations; one to the well Urðarbrunnr in the heavens, one to the spring Hvergelmir, and another to the well Mímisbrunnr. Creatures live within Yggdrasil, including the harts Dáinn, Dvalinn, Duneyrr and Duraþrór, the giant in eagle-shape Hraesvelgr, the squirrel Ratatoskr and the wyrm Níðhöggr. Scholarly theories have been proposed about the etymology of the name Yggdrasil, the potential relation to the trees Mímameiðr and Læraðr, and the sacred tree at Uppsala.

Siberian culture

The world tree is also represented in the mythologies and folklore of Northern Asia and Siberia. In the mythology of the Samoyeds, the world tree connects different realities (underworld, this world, upper world) together. In their mythology the world tree is also the symbol of Mother Earth who is said to give the Samoyed shaman his drum and also help him travel from one world to another.

The symbol of the world tree is also common in Tengriism, an ancient religion of Mongols and Turkic peoples.

The world tree is visible in the designs of the Crown of Silla, Silla being one of the Three Kingdoms of Korea. This link is used to establish a connection between Siberian peoples and those of Korea.

Mesoamerican culture and Indigenous cultures of the Americas

- Among pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cultures, the concept of "world trees" is a prevalent motif in Mesoamerican mythical cosmologies and iconography. The Temple of the Cross Complex at Palenque contains one of the most studied examples of the world tree in architectural motifs of all Mayan ruins. World trees embodied the four cardinal directions, which represented also the fourfold nature of a central world tree, a symbolic axis mundi connecting the planes of the Underworld and the sky with that of the terrestrial world.[1]

- Depictions of world trees, both in their directional and central aspects, are found in the art and mythological traditions of cultures such as the Maya, Aztec, Izapan, Mixtec, Olmec, and others, dating to at least the Mid/Late Formative periods of Mesoamerican chronology. Among the Maya, the central world tree was conceived as, or represented by, a ceiba tree, called yax imix che ('blue-green tree of abundance') by the Book of Chilam Balam of Chumayel.[2] The trunk of the tree could also be represented by an upright caiman, whose skin evokes the tree's spiny trunk.[3]

- Directional world trees are also associated with the four Yearbearers in Mesoamerican calendars, and the directional colors and deities. Mesoamerican codices which have this association outlined include the Dresden, Borgia and Fejérváry-Mayer codices.[4] It is supposed that Mesoamerican sites and ceremonial centers frequently had actual trees planted at each of the four cardinal directions, representing the quadripartite concept.

- World trees are frequently depicted with birds in their branches, and their roots extending into earth or water (sometimes atop a "water-monster", symbolic of the underworld).

- The central world tree has also been interpreted as a representation of the band of the Milky Way.[5]

- Izapa Stela 5 contains a possible representation of a world tree.

A common theme in most indigenous cultures of the Americas is a concept of directionality (the horizontal and vertical planes), with the vertical dimension often being represented by a world tree. Some scholars have argued that the religious importance of the horizontal and vertical dimensions in many animist cultures may derive from the human body and the position it occupies in the world as it perceives the surrounding living world. Many Indigenous cultures of the Americas have similar cosmologies regarding the directionality and the world tree, however the type of tree representing the world tree depends on the surrounding environment. For many Indigenous American peoples located in more temperate regions for example, it is the spruce rather than the ceiba that is the world tree; however the idea of cosmic directions combined with a concept of a tree uniting the directional planes is similar.

Other cultures

Although the concept is absent from the Greek mythology, medieval Greek folk traditions and more recent folklore claim that the tree that holds the Earth is being sawed by Kallikantzaroi (commonly translated as goblins).

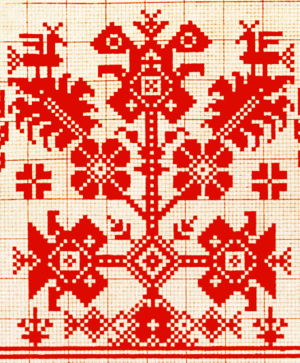

The world tree is widespread in Lithuanian folk painting, and is frequently found carved into household furniture such as cupboards, towel holders, and laundry beaters.[6][7]

The "Cosmic tree" also was one of the most important beliefs in Latvian mythology.

Remnants of the world tree concept are also evident within the history and folklore of Ireland's Gaelic past. There are many accounts within early Irish manuscripts of great tribal trees known as Bile being cut down by enemy tribes during times of war. This world tree concept, being strongly Indo-European, was likely to have been a feature of early Celtic culture.

Remnants are also evident in the Kalpavriksha ("wish-fulfilling tree") and the Ashvattha tree of the South Asian religions.

In Brahma Kumaris religion, the World Tree is portrayed as the "Kalpa Vriksha Tree", or "Tree of Humanity", in which the founder Brahma Baba (Dada Lekhraj) and his Brahma Kumaris followers are shown as the roots of the humanity who enjoy 2,500 years of paradise as living deities before trunk of humanity splits and the founders of other religions incarnate. Each creates their own branch and brings with them their own followers, until they too decline and splits. Twig like schisms, cults and sects appear at the end of the Iron Age.[8]

Popular culture

- The World Tree is present in several of the Dragon Quest video games. It is also frequently the only place where character revival items such as Yggdrasil Leaves (only one at a time, in most cases) can be obtained.

- The World Tree is also the main setting for the Nintendo Entertainment System video game Faxanadu.

- Giant magic space faring trees with great powers, artistically associating the archetypus of a World Tree, play a major role in the 1992 released Japanese anime Tenchi Muyo! Ryo-Ohki and appear in all related Series of the Tenchi Muyo! universe.

- Several World Trees also exist in the Warcraft Universe, such as Nordrassil, the World Tree which had granted the Night Elf race immortality before its destruction by Archimonde; Teldrassil, the new home to the Night Elves; and Vordrassil, the failed World Tree planted in Northrend. The concept of a World Tree is at the core of the Warcraft's Night Elven society.[9]

- The World Tree is also present in the "Sword Art Online" anime series.

- The World Tree is also present in the "Hunter X Hunter" manga and anime series.

- The "Tree of Souls", from the movie Avatar (2009).

Evolutionary origins

Some scholars suggest that the world tree is programmed into the human mind by evolutionary biology. Human beings are primates, and lived in trees for around 60 million years. The idea of a vast tree as the entirety of the world is thus still implanted in our collective unconscious.[10][11]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to World tree. |

- Cassia fistula

- It's a Big Big World, which takes place at a location called the "World Tree"

Notes

- ↑ Miller and Taube (1993), p.186.

- ↑ Roys 1967: 100

- ↑ Miller and Taube, loc. cit.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Freidel, et al. (1993)

- ↑ Straižys and Klimka, chapter 2.

- ↑ Cosmology of the Ancient Balts - 3. The concept of the World-Tree (from the 'lithuanian.net' website. Accessed 2008-12-26.)

- ↑ Walliss, John (2002). From World-Rejection to Ambivalence. Ashgate Publishing. pp. 33. ISBN 978-0-7546-0951-3.

- ↑ "Races of Warcraft - Night Elf". World of Warcraft (Game Guide). Blizzard Entertainment, Inc. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- ↑ Burkert, Creation of the Sacred

- ↑ Haycock, Being and Perceiving

References

- David Abram. The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human World, Vintage, 1997

- Burkert W (1996). Creation of the Sacred: Tracks of Biology in Early Religions. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-17570-9.

- Haycock DE (2011). Being and Perceiving. Manupod Press. ISBN 978-0-9569621-0-2.

- Roys, Ralph L., The Book of Chilam Balam of Chumayel. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press 1967.

External links

- Cosmology of the Ancient Balts by Vytautas Straižys and Libertas Klimka (Lithuanian.net)

|