Corsican language

| Corsican | |

|---|---|

| Corsu, Lingua corsa | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈkɔrsu] |

| Native to |

France Italy |

| Region |

Corsica Northern Sardinia |

Native speakers | ca. 200,000 (1993–2009)[1] |

| Latin script (Corsican alphabet) | |

| Official status | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | No official regulation |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 |

co |

| ISO 639-2 |

cos |

| ISO 639-3 |

Variously: cos – Corsican proper sdn – Gallurese sdc – Sassarese |

| Glottolog |

cors1242 (Corsican/Gallurese)[3]sass1235 (Sassarese)[4] |

| Linguasphere |

51-AAA-p |

| |

|

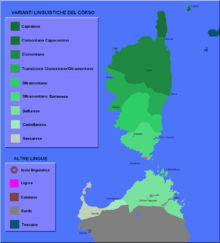

Corsican dialects | |

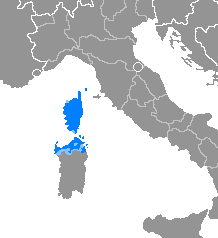

Corsican (corsu or lingua corsa) is an Italo-Dalmatian Romance language, closely related to Tuscan, spoken and written on the islands of Corsica (France) and northern Sardinia (Italy). Corsican was long the vernacular language alongside Italian, the official language in Corsica until 1859; afterwards Italian was replaced by French, owing to the acquisition of the island by France from Genoa in 1768. Over the next two centuries, the use of French grew to the extent that, by the Liberation in 1945, all islanders had a working knowledge of French. The 20th century saw a wholesale language shift, with islanders changing their language practices to the extent that there were no monolingual Corsican speakers left by the 1960s. By 1995, an estimated 65 percent of islanders had some degree of proficiency in Corsican,[5] and a small minority, perhaps 10 percent, used Corsican as a first language.[6]

Classification by subjective analysis

One of the main sources of confusion in popular classifications is the difference between a dialect and a language. Typically it is not possible to ascertain what an author means by these terms. For example, one might read that Corsican is a "central southern Italian dialect" along with Tuscan, Neapolitan, Sicilian and others[7] or that it is "closely related to the Tuscan dialect of Italian".[8]

One of the characteristics of Italian but not of modern Tuscan is the retention of the -re infinitive ending as in Latin mittere, "send", which is lost in Corsican (and in modern Tuscan), which has mette/metta, "to put." The Latin relative pronoun, "who," "qui," "quae," and "what," "quod," are inflected in Latin while relative pronoun in Italian for "who" and "what" is "chi", "che cosa" and in Corsican, it is uninflected chì.

Origins

The Corsican language has been influenced by the languages of the major powers taking an interest in Corsican affairs; earlier by those of the medieval Italian powers: Tuscany (828–1077), Pisa (1077–1282) and Genoa (1282–1768), more recently by France (1768–present), which, since 1789, has promulgated the official Parisian French. The term gallicised Corsican refers to Corsican up to about the year 1950. The term distanciated Corsican refers to an idealized Corsican from which various agents have removed French or other elements.[9]

The general classification of Corsican as a Romance language allows two possibilities as to the identity of the speakers of the first distinct Corsican, or Proto-Corsican. They created the language either from Proto-Romance or from a subsequent Romance language.

In 40 AD, neither a Romance nor an Italic language were spoken by the natives of Corsica. The Roman exile, Seneca the younger, reports that both coast and interior were occupied by natives whose language he did not understand (see under Prehistory of Corsica). Latin at that time was generally spoken only in the Roman colonies. There was probably a sub language that is still visible in the toponymy or in some words, for instance Gallurese zerru 'pig'. The same is valid for Sardinian. The occupation of the island by Vandals about 469 AD marked the end of authoritative influence by Latin-speaking Romans (see under Medieval Corsica). If the natives of that time were speaking Latin they must have acquired it during the late empire. The documents of the early Christian church concerning Corsica are in Latin, but they are only communications between church officials (see Ajaccio).

The next window of opportunity for the predecessor of a Proto-Corsican was the administration of Corsica by Tuscany, then speaking the Tuscan dialect, an immediate predecessor of Italian. The first Italian documents date from the 10th century but Italian must have developed earlier and Tuscan even earlier. Tuscan would have come from the latest phases of Vulgar Latin; Proto-Corsican from the Tuscan spoken on Corsica.

The last historical possibility is that Proto-Corsican came from the Tuscan dialect of Pisa; its period of Corsican administration, however, was relatively short. Genoese is not a likely possibility as Corsican is attested before the presence of Genoa on Corsica, and the linguistic features of Corsican do not match well with those of Genoese. Historical circumstances alone reduce the window of opportunity only to within several hundred years.

Dialects

Corsica

The two most widely spoken forms of the Corsican language are Supranacciu or Cismonticu, spoken in the Bastia and Corte area (generally throughout the northern half of the island, known as Haute-Corse or Corsica suprana), and Suttanacciu or Pumonticu, spoken around Sartène and Porto-Vecchio (generally throughout the southern half of the island, known as Corse-du-Sud or Corsica suttana). The dialect of Ajaccio has been described as in transition. The dialects spoken at Calvi and Bonifacio are closer to the Genoese dialect, also known as Ligurian.

This division along the Girolata-Porto Vecchio line was due to the massive immigration from Tuscany which took place in Corsica during the lower Middle Ages: as a result, the northern Corsican dialects became very close to a central Italian lect like Tuscan, while the southern Corsican varieties could keep the original characteristics of the language which make it much more similar to Sicilian and, to some extent, Sardinian.

Sardinia

Gallurese is spoken in the extreme north of Sardinia, including the region of Gallura and the archipelago of La Maddalena, and Sassarese is spoken in Sassari and in its neighbourhood, in the north-west of Sardinia. Whether these two lects should be included either in Corsican or in the Sardinian language as dialects, or considered independent languages, is still subject of debate.

On Maddalena archipelago the local dialect (called Isulanu, Maddaleninu, Maddalenino) was brought by fishermen and shepherds from Bonifacio during immigration in the 17th-18th centuries. Though influenced by Gallurese it has maintained the original characteristics of Corsican. There are also numerous words of Genoese and Ponzese origin.[1]

On 15 October 1997, Article 2 Item 4 of Law Number 26 of the Autonomous Region of Sardinia granted "al dialetto sassarese e a quello gallurese" – equal legal status with the other languages on Sardinia. They are thus legally defined as different languages from Sardinian by the Sardinian government.[10]

Number of speakers

The January 2007 estimated population of Corsica was 281,000, while the figure for the March 1999 census, when most of the studies – though not the linguistic survey work referenced in this article – were performed, was about 261,000 (see under Corsica). Only a fraction of the population at either time spoke Corsican with any fluency.

The use of Corsican language over French language has been declining. In 1980 about 70 percent of the population of the island "had some command of the Corsican language."[11] In 1990 out of a total population of about 254,000 the percentage had declined to 50 percent, with only 10 percent using it as a first language.[6] (These figures do not count varieties of Corsican spoken in Sardinia.) The language appeared to be in serious decline when the French government reversed its unsupportive stand and initiated some strong measures to save it.

According to an official survey run on behalf of the Collectivité territoriale de Corse which took place in April 2013, in Corsica the Corsican language has a number of speakers situated between 86,800 and 130,200, out of a total population amounting to 309,693 inhabitants.[12] The percentage of those who have a solid knowledge of the language varies between a minimum of 25 percent in the 25-34 age group and the maximum of 65 percent in the over-65 age group: almost a quarter of the former age group does not understand Corsican, while only a small minority of the older people do not understand it.[12] While 32 percent of the population of northern Corsica speaks Corsican quite well, this percentage drops to 22 percent for South Corsica.[12] Moreover, 10 percent of the population of Corsica speaks only French, while 62 percent speak both French and Corsican.[12] However, only 8 percent of the Corsicans know how to write correctly in Corsican, while about 60 percent of the population does not know how to write in Corsican.[12] While 90 percent of the population is in favor of a Corsican-French bilingualism, 3 percent would like to have Corsican as the only official language in the island, and 7 percent would prefer French in this role.[12]

UNESCO classifies Corsican as a "definitely endangered language."[13] The Corsican language is a key vehicle for Corsican culture, which is notably rich in proverbs and in polyphonic song.

Governmental support

The 1991 "Joxe Statute", in setting up the Collectivité Territoriale de Corse, also provided for the Corsican Assembly, and charged it with developing a plan for the optional teaching of Corsican. The University of Corsica Pascal Paoli at Corte took a central role in the planning.[14]

At the primary school level Corsican is taught up to a fixed number of hours per week (three in the year 2000) and is a voluntary subject at the secondary school level,[15] but is required at the University of Corsica. It is available through adult education. It can be spoken in court or in the conduct of other government business if the officials concerned speak it. The Cultural Council of the Corsican Assembly advocates for its use; for example, on public signs.

Literature

According to the anthropologist Dumenica Verdoni, writing new literature in modern Corsican, known as the Riacquistu, is an integral part of affirming Corsican identity.[16] Persons who had a notable career in France returned to Corsica to write in Corsican, such as the musical producers, Dumenicu Togniotti, director of the Teatru Paisanu, which produced polyphonic musicals, 1973–1982, followed in 1980 by Michel Raffaelli's Teatru di a Testa Mora, and Saveriu Valentini's Teatru Cupabbia in 1984.[17] The list of prose writers includes Alanu di Meglio, Ghjacumu Fusina, Lucia Santucci, Marcu Biancarelli,and many others.[18]

Throughout the 1700s and 1800s there was a steady stream of writers in Corsican, many of whom wrote also in other languages.[19]

Ferdinand Gregorovius, 19th century traveller and enthusiast of Corsican culture, reported that the preferred form of the literary tradition of his time was the vocero, a type of polyphonic ballad originating from funeral obsequies. These laments were similar in form to the chorales of Greek drama except that the leader could improvise. Some performers were noted at this, such as the 1700s Mariola della Piazzole and Clorinda Franseschi.[20]

The trail of written popular literature of known date in Corsican currently goes no further back than the 17th century.[21] An undated corpus of proverbs from communes may well precede it (see under External links below). Corsican has also left a trail of legal documents ending in the late 12th century. At that time the monasteries held considerable land on Corsica and many of the churchmen were notaries.

Between 1200 and 1425 the monastery of Gorgona, Benedictine for much of that time and in the territory of Pisa, acquired about 40 legal papers of various sorts written on Corsica. As the church was replacing Pisan prelates with Corsican ones there the legal language shows a transition from entirely Latin through partially Latin, partially Corsican to entirely Corsican. The first known surviving document containing some Corsican is a bill of sale from Patrimonio dated to 1220.[22] These documents were moved to Pisa before the monastery closed its doors and were published there. Research into earlier evidence of Corsican is ongoing.

Alphabet and spelling

Corsican is written in the standard Latin script, using 22 of the letters for native words. The letters k, w, x, and y are found only in foreign names and French vocabulary. The digraphs and trigraphs chj', ghj, sc and sg are also defined as "letters" of the alphabet in its modern scholarly form (compare the presence of ch or ll in the Spanish alphabet) and appear respectively after c, g and s.

The primary diacritic used is the grave accent, indicating word stress when it is not penultimate. In scholarly contexts, disyllables may be distinguished from diphthongs by use of the diaeresis on the former vowel (as in Italian and distinct from French and English). In older writing, the acute accent is sometimes found on stressed ⟨e⟩, the circumflex accent on stressed ⟨o⟩, indicating respectively (/e/) and (/o/) phonemes.

Corsican has been regarded as a dialect of Italian historically, similar to the regional Romance languages in Italy proper, and in writing, it often resembles Italian (with the substitution of -u for final -o and the articles u and a for il/lo and la respectively). However, the phonemes of the modern spoken forms of Corsican undergo complex and sometimes irregular phenomena depending on phonological context so the pronunciation of the language for foreigners familiar with other Romance languages is not straightforward.

Phonology

Vowels

As in Italian, the grapheme ⟨i⟩ appears in some digraphs and trigraphs in which it does not represent the phonemic vowel. All vowels are pronounced except in a few well-defined instances. ⟨i⟩ is not pronounced before ⟨a⟩, ⟨o⟩, ⟨u⟩ after ⟨sc⟩, ⟨sg⟩, ⟨c⟩ and ⟨g⟩: sciarpa [ˈʃarpa]; or initially in some words: istu [ˈstu].[23]

Vowels may be nasalized before ⟨n⟩ (which is assimilated to ⟨m⟩ before ⟨p⟩ or ⟨b⟩) and the palatal nasal consonant represented by ⟨gn⟩. The nasal vowels are represented by the vowel plus ⟨n⟩, ⟨m⟩ or ⟨gn⟩. The combination is a digraph or trigraph indicating the nasalized vowel. The consonant is pronounced in weakened form. The same combination of letters might not be the digraph or trigraph but might be just the non-nasal vowel followed by the consonant at full weight. The speaker must know the difference. Example of nasal: ⟨pane⟩ is pronounced [ˈpãnɛ] and not [ˈpanɛ].

The vowel inventory, or collection of phonemic vowels (and the major allophones), transcribed in IPA symbols, is:[24][25]

| Description | Grapheme (Minuscule) |

Phoneme | Phone or Allophones |

Usage | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open front unrounded Near open |

a | /a/ | [a] [æ] |

Occasional northern |

casa [ˈkaza] carta [ˈkærta] |

| Open back unrounded | â | /ɑ/ | [ɑ] | ||

| Close-mid front unrounded Open-mid Near-open Open |

e | /e/ | [e] [ɛ] [æ] [a] |

Inherited as open or close Occasional southern Occasional southern |

U celu [uˈd͡ʒelu] Ci hè [ˈt͡ʃɛ] terra [ˈtarra] |

| Close front unrounded | i | /i/ | [i] [j] |

1st sound, diphthong |

mi [mi] fiume [ˈfjumɛ] |

| Close-mid back rounded | o | /o/ | [o] | giòvani [ˈd͡ʒowãni] | |

| Close back rounded | u | /u/ | [u] [w] |

1st sound, diphthong |

malu [ˈmalu] bad guida [ˈɡwida] guide |

Consonants

| Bilabial | Labio- dental |

Alveolar /Dental |

Palato- alveolar |

Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | labial. | ||||||||

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ||||||

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t̪ | c | k | kʷ | |||

| voiced | b | d̪ | ɖ | ɟ | g | ɡʷ | |||

| Affricate | voiceless | t͡s̪ | t͡ʃ | ||||||

| voiced | d͡z̪ | d͡ʒ | |||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s̪ | ʃ | |||||

| voiced | β | v | ʒ | ||||||

| Approximant | central | j | w | ||||||

| lateral | l | ʎ | |||||||

| Trill | ɲ | ||||||||

See also

References

- 1 2 Corsican proper at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

Gallurese at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

Sassarese at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) - ↑ Harris, Martin; Vincent, Nigel (1997). Romance Languages. London: Routlegde. ISBN 0-415-16417-6.

- ↑ Nordhoff, Sebastian; Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2013). "Corsic". Glottolog. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

- ↑ Nordhoff, Sebastian; Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2013). "Sassarese Sardinian". Glottolog. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

- ↑ http://www.unesco.org/languages-atlas/en/atlasmap/language-id-340.html

- 1 2 "Corsican in France". Euromosaic. Retrieved 2008-06-13. To access the data, click on List by languages, Corsican, Corsican in France, then scroll to Geographical and language background.

- ↑ Italian Language. Encarta. Archived from the original on 2009-10-31. Retrieved 2008-06-13.

- ↑ "Eurolang report on Corsican". Retrieved 2008-06-13.

- ↑ Blackwood, Robert J. (August 2004). "Corsican distanciation strategies: Language purification or misguided attempts to reverse the gallicisation process?" (PDF). Multilingua – Journal of Cross-Cultural and Interlanguage Communication 23 (3): 233–255. doi:10.1515/mult.2004.011. Retrieved 2008-06-13.

- ↑ Autonomous Region of Sardinia (1997-10-15). "Legge Regionale 15 ottobre 1997, n. 26" (in Italian). pp. Art. 2, paragraph 4. Retrieved 2008-06-16.

- ↑ "Corsican language use survey". Euromosaic. Retrieved 2008-06-13. To find this statement and the supporting data click on List by languages, Corsican, Corsican language use survey and look under INTRODUCTION.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Inchiesta sociolinguistica nant'à a lingua corsa". www.corse.fr (in Corsican). Collectivité territoriale de Corse. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- ↑ Moseley, Christopher (ed.). 2010. Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger, 3rd edn. Paris, UNESCO Publishing. Here is the online version

- ↑ Daftary, Farimah (October 2000). "Insular Autonomy: A Framework for Conflict Settlement? A Comparative Study of Corsica and the Åland Islands" (PDF). European Centre For Minority Issues (ECMI). pp. 10–11. Retrieved 2008-06-13.

- ↑ (French) Dispositif académique d’enseignement de la langue corse dans le premier degré, année scolaire 2010-2011, Academy of Corsica

- ↑ Verdoni, Dumenica. "Etat/identités:de la culture du conflit à la culture du projet". InterRomania (in French). Centru Culturale Universita di Corsica. Retrieved 2008-06-17.

- ↑ Magrini, Tullia (2003). Music and Gender: Perspectives from the Mediterranean. University of Chicago Press. p. 53. ISBN 0-226-50166-3.

- ↑ Filippi, Paul-Michel (2008). "Corsican Literature Today". Transcript (17). Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- ↑ "Auteurs". ADECEC.net. Archived from the original on 27 June 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-28.

- ↑ Gregorovius, Ferndinand (1855). Corsica in Its Picturesque, Social, and Historical Aspects: the Records of a Tour in the Summer of 1852. Russell Martineau (trans.). London: Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans. pp. 275–312.

- ↑ Beretti, Francis (Translator) (2008). "The Corsican Language". Transcript (17). Retrieved 2008-06-29.

- ↑ Scalfati, Silio P. P. (2003). "Latin et langue vernaculaire dans les actes notariés corses XIe-XVe siècle". La langue des actes. XIe Congrès international de diplomatique (Troyes, 11–13 September 2003). Éditions en ligne de l'École des chartes. Retrieved October 30, 2011.

- ↑ "La prononciation des voyelles". A Lingua Corsa. April 19, 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-20.

- ↑ Ager, Simon (1998–2008). "Corsican (corsu)". Omniglot. Retrieved 2008-06-20.

- ↑ "Notes sur la phonétique utilisée sur ce site". A Lingua Corsa. April 19, 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-20.

Bibliography

- Jaffe, Alexandra (1999). Ideologies in Action: Language Politics on Corsica. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-016445-0.

External links

| Corsican edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Corsican language. |

| Wikivoyage has a phrasebook for Corsican. |

- Corsican language, alphabet and pronunciation

- "INFCOR: Banca di dati di a lingua corsa". L'ADECEC (Association pour le Développement des Etudes Archéologiques, Historiques, linguistiques et Naturalistes du Centre-Est de la Corse). Retrieved 2008-06-13.

- "Patre Nostru". prayer.su. Retrieved 2008-06-25.

- "Traduction Corse – Latin". A lingua corsa. Retrieved 2008-06-13.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||