Cornish engine

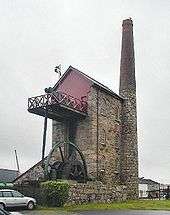

A Cornish engine is a type of steam engine developed in Cornwall, England, mainly for pumping water from a mine. It is a form of beam engine that uses steam at a higher pressure than the earlier engines designed by James Watt. The engines were also used for powering man engines to assist the underground miners' journeys to and from their working levels, for winching materials into and out of the mine and for powering the ore stamping machinery.[1]

The Cornish cycle

The Cornish cycle operates as follows.[2]

Starting from a condition during operation with the piston at the top of the cylinder, the cylinder below the piston full of steam from the previous stroke, the boiler at normal working pressure, and the condenser at normal working vacuum,

- The inlet and exhaust valves are opened. Steam from the boiler enters the top of the cylinder above the piston, and the steam below the piston is drawn into the condenser creating a vacuum below the piston. The pressure difference between the steam at boiler pressure above the piston and the vacuum below it drives the piston down.

- Part way down the stroke the inlet valve is closed. The steam above the piston then expands through the rest of the stroke.

- At the bottom of the stroke the exhaust valve is closed and the equilibrium valve opened. The weight of the pump gear draws the piston up and, as the piston comes up, steam is transferred through the equilibrium pipe from above the piston to the bottom of the cylinder below the piston.

- When the piston reaches the top of the cylinder the cycle is ready to repeat.

The next stroke may occur immediately, or it may be delayed by a timing device such as a cataract. If it was not necessary for the engine to work at its maximum rate, reducing the rate of operation saved fuel.

The engine is single-acting and the steam piston is pulled up by the weight of the pump piston and rodding. Steam may be supplied at a pressure of up to 50 pounds per square inch (340 kPa).

Characteristics

The principal advance of the Cornish engine was its increase in efficiency due to expansive working of the steam. Improvements in efficiency were important in Cornwall because of the high cost of coal. There are no coal fields in Cornwall and all the coal used had to be brought in from outside the county.

Increasing the boiler pressure above the very low, virtually atmospheric, steam pressure used by James Watt was an essential element of the improvement in efficiency of the Cornish engine. However, simply increasing the boiler pressure would have made an engine more powerful without increasing its efficiency. The key advance was allowing the steam to expand in the cylinder. James Watt had conceived the idea of expansive working of steam and included it in his 1782 patent, but he realised that the low steam pressure he used made the improvement in efficiency negligible and he did not pursue it.

In a Watt engine, steam was admitted throughout the stroke. At the end of the stroke, all of the energy contained in the steam was lost to the condenser cooling water.

In a Cornish engine, the inlet of steam was cut off part way through the down stroke, allowing the steam already in the cylinder to expand through the rest of the stroke to a lower pressure. This resulted in the steam giving up a greater proportion of its energy as useful work, and proportionally less heat being lost to the condenser cooling water, than in a Watt engine.

Other characteristics include insulation of steam lines and the cylinder, and steam jacketing the cylinder, both of which had previously been used by Watt.[3]

A Cornish engine pumps by a falling weight that is lifted by the engine. Few remain in their original locations, the majority having been scrapped when their related industrial firm closed.[1]

The Cornish engine developed irregular power throughout the cycle, completely pausing at one point while having rapid motion on the down stroke, making it unsuitable for rotary motion and most industrial applications.[3]

Background: the steam engine in Cornwall

Cornwall has long had mines for tin, copper and other metal ores, but if mining is to take place below adit (essentially, the level of an entrance which can both drain and ventilate the diggings), some means of draining water from the mine must be found . This may be done using horse power or a waterwheel to operate pumps, but horses have limited power and waterwheels need a suitable stream of water. Accordingly, the conversion of coal into power to work pumps was highly desirable to the mining industry.

Wheal Vor (mine) had one of the earliest Newcomen engines (in-cylinder condensing engines, utilising sub-atmosperic pressure) before 1714, but Cornwall has no coalfield and coal imported from south Wales was expensive. The cost of fuel for pumping was thus a significant part of mining costs. Later, many of the more efficient early Watt engines (using an external condenser) were erected by Boulton and Watt in Cornwall. They charged the mine owners a royalty based on a share of the fuel saving. The fuel efficiency of an engine was measured by its "duty", expressed in the work (in foot-pounds) generated by a bushel (94 pounds (43 kg)) of coal. Early Watt engines had a duty of 20 million, and later ones over 30 million.[4]

Development of the Cornish engine

The Cornish engine depended on the use of steam pressure above atmospheric pressure, as devised by Richard Trevithick in the 19th century. Trevithick's early "puffer" engines discharged steam into the atmosphere. This differed from the Watt steam engine, which used low pressure steam and so depended in part on the creation of a vacuum when the steam was condensed. Trevithick's later ones (in the 1810s) combined the two principles, starting with high pressure steam but also condensing it in a separate condenser. In a parallel development Arthur Woolf developed the compound steam engine, in which the steam expanded in two cylinders successively.[4]

When Trevithick left for South America in 1816 he passed his patent right to his latest invention to William Sims, who built (or adapted) a number of engines, including one at Wheal Chance operating at 40 pounds per square inch (280 kPa) above atmospheric pressure, which achieved a duty of nearly 50 million, but its duty then fell back. A test was carried out between a Trevithick type single-cylinder engine and a Woolf compound engine at Wheal Alfred in 1825, when both achieved a duty of slightly more than 40 million.[5]

The next improvement was achieved in the late 1820s by Samuel Grose, who decreased the heat loss by insulating the pipes, cylinders, and boilers of the engines, improving the duty to more than 60 million at Wheal Hope and later to almost 80 million at Wheal Towan. Nevertheless, the best duty was usually a short-lived achievement due to general deterioration of machinery, leaks from boilers, and the deterioration of boiler plates (meaning that pressure had to be reduced).[5]

Minor improvements increased the duty somewhat, but the engine seems to have reached its practical limits by the mid-1840s. With pressures of up to 50 pounds per square inch (340 kPa), the shocks are likely to have caused machinery breakages. The same improvements in duty occurred in engines operating Cornish stamps and whims, but generally came slightly later. In both cases the best duty was lower than for pumping engines, particularly so for whim engines, whose work was discontinuous.[4]

The impetus for the improvement of the steam engine came from Cornwall because of the high price of coal there, but both capital and maintenance costs were higher than a Watt steam engine. This long delayed the installation of Cornish engines outside Cornwall. A second hand Cornish engine was installed at East London Waterworks in 1838, and compared to a Watt engine with favourable results, because the price of coal in London was even higher than in Cornwall. However, in the main textile manufacturing areas, such as Manchester and Leeds, the coal price was too low to make replacement economic. Only in the late 1830s did textile manufacturers begin moving to high pressure engines, usually by adding a high pressure cylinder, forming a compound engine, rather than following the usual Cornish practice.[4]

Preserved Cornish engines

Several Cornish engines are preserved in England. The London Museum of Water & Steam has the largest collection of Cornish engines in the world. At Crofton Pumping Station, in Wiltshire, a Grade 1 listed building houses two Cornish engines, one of which (the 1812 Boulton and Watt) is the "oldest working beam engine in the world still in its original engine house and capable of actually doing the job for which it was installed", that of pumping water to the summit pound of the Kennet and Avon Canal.[6] Two examples also survive at the Cornish Mines and Engines museum on the site of East Pool mine near the town of Pool, Cornwall.

Another example is at Poldark Mine (Trenear, Cornwall) - Harvey of Hale Cornish Beam Engine from Bunny Tin Mine and later Greensplat China Clay Pit )both near St Austell dating from about 1840 - 1850. Hydraulic mechanism added for demonstration purposes. Last engine to have worked commercially in Cornwall to Christmas week 1959, moved to Poldark in 1972 [[7]]

The Cruquius pumping station in the Netherlands contains a Cornish engine with the largest diameter cylinder ever built for a Cornish engine, at 3.5 metre diameter (144 inches). The engine, which was built by Harvey & Co in Hayle, Cornwall, England, has eight beams connected to the one cylinder, each beam driving a single pump.[8] The engine was restored to working order between 1985 and 2000, although it is now operated by an oil-filled hydraulic system, since restoration to steam operation was not viable.[9]

The Trevithick Society, a forerunner of Industrial Archaeology organisations that was initially formed to rescue the Levant winding engine from being scrapped was named for Richard Trevithick. They acquired another winding engine and two pumping engines.[10] They publish a newsletter, a journal and many books on Cornish engines, the mining industry, engineers, and other industrial archaeological topics.[11][12]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cornish engines. |

- Beam engine

- Mining in Devon and Cornwall

- Stationary steam engine

- Lean's Engine Reporter

- Cataract (beam engine)

References

- 1 2 Barton, D. B. (1966). The Cornish Beam Engine (New ed.). Truro: D. Bradford Barton.

- ↑ http://www.croftonbeamengines.org/page13.html

- 1 2 Hunter, Louis C. (1985). A History of Industrial Power in the United States, 1730-1930, Vol. 2: Steam Power. Charolttesville: University Press of Virginia.

- 1 2 3 4 Nuvolari, Alessandro; Verspagen, Bart (2009). "Technical choice, innovation and British steam engineering, 1800-1850". Economic History Review 63 (3): 685–710.

- 1 2 Nuvolari, Alessandro; Verspagen, Bart (2007). "Lean's Engine Reporter and the Cornish Engine". Transactions of the Newcomen Society 77 (2): 167–190. doi:10.1179/175035207X204806.

- ↑ "Crofton".

- ↑ Fyfield-Shayler. The Making of Wendron. Graphmitre Ltd archive date=1972.

- ↑ "Construction". Cruquius Museum. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- ↑ "Hydraulic". Cruquius Museum. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- ↑ Trevithick Society. Open Lectures and Talks. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- ↑ Trevithick Society. The Journal of the Trevithick Society, Issues 6-10. Trevithick Society, 1978.

- ↑ Trevithick Society. Cornish Miner - Books on Cornwall. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

External links

- Cornish beam engine animation

- Cornish engines in Pool

- Cruquius pumping station (includes mechanical details, simulations, technical drawings, etc.)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||