Copper

Native copper (~4 cm in size) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| General properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name, symbol | copper, Cu | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | red-orange metallic luster | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pronunciation |

/ˈkɒpər/ KOP-ər | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Copper in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 29 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group, block | group 11, d-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Element category | transition metal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight (±) (Ar) | 63.546(3)[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Ar] 3d10 4s1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

per shell | 2, 8, 18, 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 1357.77 K (1084.62 °C, 1984.32 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 2835 K (2562 °C, 4643 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density near r.t. | 8.96 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid, at m.p. | 8.02 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 13.26 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 300.4 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 24.440 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | −2, +1, +2, +3, +4 (a mildly basic oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 1.90 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

1st: 745.5 kJ/mol 2nd: 1957.9 kJ/mol 3rd: 3555 kJ/mol (more) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 128 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 132±4 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 140 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Miscellanea | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure |

face-centered cubic (fcc)  | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod |

(annealed) 3810 m/s (at r.t.) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 16.5 µm/(m·K) (at 25 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 401 W/(m·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 16.78 nΩ·m (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | diamagnetic[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young's modulus | 110–128 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | 48 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 140 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Poisson ratio | 0.34 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 3.0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vickers hardness | 343–369 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brinell hardness | 235–878 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7440-50-8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Naming | after Cyprus, principal mining place in Roman era (Cyprium) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Middle East (9000 BCE) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Most stable isotopes of copper | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Copper is a chemical element with symbol Cu (from Latin: cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a reddish-orange color. It is used as a conductor of heat and electricity, as a building material, and as a constituent of various metal alloys.

Copper is found as a pure metal in nature, and this was the source of the first metal to be used by humans, ca. 8,000 BC; it was the first metal to be smelted from its ore, ca. 5,000 BC; it was the first metal to be cast into a shape in a mold, ca. 4,000 BC; and it was the first metal to be purposefully alloyed with another metal, tin, to create bronze, ca. 3,500.[3]

In the Roman era, copper was principally mined on Cyprus, the origin of the name of the metal from aes сyprium (metal of Cyprus), later corrupted to сuprum, from which the words copper (English), cuivre (French), Koper (Dutch) and Kupfer (German) are all derived.[4] Its compounds are commonly encountered as copper(II) salts, which often impart blue or green colors to minerals such as azurite, malachite and turquoise and have been widely used historically as pigments. Architectural structures built with copper corrode to give green verdigris (or patina). Decorative art prominently features copper, both by itself and in the form of pigments.

Copper is essential to all living organisms as a trace dietary mineral because it is a key constituent of the respiratory enzyme complex cytochrome c oxidase. In molluscs and crustacea copper is a constituent of the blood pigment hemocyanin, which is replaced by the iron-complexed hemoglobin in fish and other vertebrates. The main areas where copper is found in humans are liver, muscle and bone.[5] Copper compounds are used as bacteriostatic substances, fungicides, and wood preservatives.

Characteristics

Physical

Copper, silver and gold are in group 11 of the periodic table, and they share certain attributes: they have one s-orbital electron on top of a filled d-electron shell and are characterized by high ductility and electrical conductivity. The filled d-shells in these elements do not contribute much to the interatomic interactions, which are dominated by the s-electrons through metallic bonds. Unlike metals with incomplete d-shells, metallic bonds in copper are lacking a covalent character and are relatively weak. This explains the low hardness and high ductility of single crystals of copper.[6] At the macroscopic scale, introduction of extended defects to the crystal lattice, such as grain boundaries, hinders flow of the material under applied stress, thereby increasing its hardness. For this reason, copper is usually supplied in a fine-grained polycrystalline form, which has greater strength than monocrystalline forms.[7]

The softness of copper partly explains its high electrical conductivity (59.6×106 S/m) and thus also high thermal conductivity, which are the second highest (to silver) among pure metals at room temperature.[8] This is because the resistivity to electron transport in metals at room temperature mostly originates from scattering of electrons on thermal vibrations of the lattice, which are relatively weak for a soft metal.[6] The maximum permissible current density of copper in open air is approximately 3.1×106 A/m2 of cross-sectional area, above which it begins to heat excessively.[9] As with other metals, if copper is placed against another metal, galvanic corrosion will occur.[10]

Together with caesium and gold (both yellow), and osmium (bluish), copper is one of only four elemental metals with a natural color other than gray or silver.[11] Pure copper is orange-red and acquires a reddish tarnish when exposed to air. The characteristic color of copper results from the electronic transitions between the filled 3d and half-empty 4s atomic shells – the energy difference between these shells is such that it corresponds to orange light. The same mechanism accounts for the yellow color of gold and caesium.[6]

Chemical

Copper does not react with water but it does slowly react with atmospheric oxygen to form a layer of brown-black copper oxide which, unlike the rust which forms when iron is exposed to moist air, protects the underlying copper from more extensive corrosion. A green layer of verdigris (copper carbonate) can often be seen on old copper constructions such as the Statue of Liberty.[12] Copper tarnishes when exposed to sulfides, which react with it to form various copper sulfides.[13]

Isotopes

There are 29 isotopes of copper. 63Cu and 65Cu are stable, with 63Cu comprising approximately 69% of naturally occurring copper; they both have a spin of 3⁄2.[14] The other isotopes are radioactive, with the most stable being 67Cu with a half-life of 61.83 hours.[14] Seven metastable isotopes have been characterized, with 68mCu the longest-lived with a half-life of 3.8 minutes. Isotopes with a mass number above 64 decay by β−, whereas those with a mass number below 64 decay by β+. 64Cu, which has a half-life of 12.7 hours, decays both ways.[15]

62Cu and 64Cu have significant applications. 62Cu is used in 62Cu-PTSM that is a radioactive tracer for positron emission tomography.[16]

Occurrence

Copper is synthesized in massive stars[17] and is present in the Earth's crust at a concentration of about 50 parts per million (ppm),[18] where it occurs as native copper or in minerals such as the copper sulfides chalcopyrite and chalcocite, the copper carbonates azurite and malachite, and the copper(I) oxide mineral cuprite.[8] The largest mass of elemental copper discovered weighed 420 tonnes and was found in 1857 on the Keweenaw Peninsula in Michigan, US.[18] Native copper is a polycrystal, with the largest described single crystal measuring 4.4×3.2×3.2 cm.[19]

Production

Most copper is mined or extracted as copper sulfides from large open pit mines in porphyry copper deposits that contain 0.4 to 1.0% copper. Examples include Chuquicamata in Chile, Bingham Canyon Mine in Utah, United States and El Chino Mine in New Mexico, United States. According to the British Geological Survey, in 2005, Chile was the top mine producer of copper with at least one-third world share followed by the United States, Indonesia and Peru.[8] Copper can also be recovered through the in-situ leach process. Several sites in the state of Arizona are considered prime candidates for this method.[20] The amount of copper in use is increasing and the quantity available is barely sufficient to allow all countries to reach developed world levels of usage.[21]

Reserves

Copper has been in use at least 10,000 years, but more than 95% of all copper ever mined and smelted has been extracted since 1900,[22] and more than half was extracted in only the last 24 years. As with many natural resources, the total amount of copper on Earth is vast (around 1014 tons just in the top kilometer of Earth's crust, or about 5 million years' worth at the current rate of extraction). However, only a tiny fraction of these reserves is economically viable, given present-day prices and technologies. Various estimates of existing copper reserves available for mining vary from 25 years to 60 years, depending on core assumptions such as the growth rate.[23] Recycling is a major source of copper in the modern world.[22] Because of these and other factors, the future of copper production and supply is the subject of much debate, including the concept of peak copper, analogous to peak oil.

The price of copper has historically been unstable,[24] and it sextupled from the 60-year low of US$0.60/lb (US$1.32/kg) in June 1999 to US$3.75 per pound (US$8.27/kg) in May 2006. It dropped to US$2.40/lb (US$5.29/kg) in February 2007, then rebounded to US$3.50/lb (US$7.71/kg) in April 2007.[25] In February 2009, weakening global demand and a steep fall in commodity prices since the previous year's highs left copper prices at US$1.51/lb (US$3.32/kg).[26]

Methods

.svg.png)

The concentration of copper in ores averages only 0.6%, and most commercial ores are sulfides, especially chalcopyrite (CuFeS2) and to a lesser extent chalcocite (Cu2S).[27] These minerals are concentrated from crushed ores to the level of 10–15% copper by froth flotation or bioleaching.[28] Heating this material with silica in flash smelting removes much of the iron as slag. The process exploits the greater ease of converting iron sulfides into its oxides, which in turn react with the silica to form the silicate slag, which floats on top of the heated mass. The resulting copper matte consisting of Cu2S is then roasted to convert all sulfides into oxides:[27]

- 2 Cu2S + 3 O2 → 2 Cu2O + 2 SO2

The cuprous oxide is converted to blister copper upon heating:

- 2 Cu2O → 4 Cu + O2

The Sudbury matte process converted only half the sulfide to oxide and then used this oxide to remove the rest of the sulfur as oxide. It was then electrolytically refined and the anode mud exploited for the platinum and gold it contained. This step exploits the relatively easy reduction of copper oxides to copper metal. Natural gas is blown across the blister to remove most of the remaining oxygen and electrorefining is performed on the resulting material to produce pure copper:[29]

- Cu2+ + 2 e− → Cu

Recycling

Like aluminium, copper is 100% recyclable without any loss of quality, regardless of whether it is in a raw state or contained in a manufactured product. In volume, copper is the third most recycled metal after iron and aluminium. It is estimated that 80% of the copper ever mined is still in use today.[30] According to the International Resource Panel's Metal Stocks in Society report, the global per capita stock of copper in use in society is 35–55 kg. Much of this is in more-developed countries (140–300 kg per capita) rather than less-developed countries (30–40 kg per capita).

The process of recycling copper is roughly the same as is used to extract copper but requires fewer steps. High-purity scrap copper is melted in a furnace and then reduced and cast into billets and ingots; lower-purity scrap is refined by electroplating in a bath of sulfuric acid.[31]

Alloys

Numerous copper alloys exist, many with important uses. Brass is an alloy of copper and zinc. Bronze usually refers to copper-tin alloys, but can refer to any alloy of copper such as aluminium bronze. Copper is one of the most important constituents of carat silver and gold alloys, and carat solders are used in the jewelry industry, modifying the color, hardness and melting point of the resulting alloys.[32]

The alloy of copper and nickel, called cupronickel, is used in low-denomination coins, often for the outer cladding. The US 5-cent coin called a nickel consists of 75% copper and 25% nickel and has a homogeneous composition. The alloy consisting of 90% copper and 10% nickel is remarkable for its resistance to corrosion and is used in various parts that are exposed to seawater. Alloys of copper with aluminium (about 7%) have a pleasant golden color and are used in decorations.[18] Some lead-free solders consist of tin alloyed with a small proportion of copper and other metals.[33]

Compounds

Copper forms a rich variety of compounds, usually with oxidation states +1 and +2, which are often called cuprous and cupric, respectively.[34]

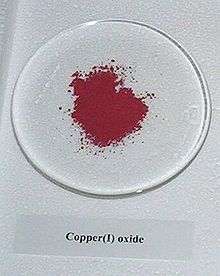

Binary compounds

As with other elements, the simplest compounds of copper are binary compounds, i.e. those containing only two elements. The principal ones are the oxides, sulfides, and halides. Both cuprous and cupric oxides are known. Among the numerous copper sulfides, important examples include copper(I) sulfide and copper(II) sulfide.

The cuprous halides with chlorine, bromine, and iodine are known, as are the cupric halides with fluorine, chlorine, and bromine. Attempts to prepare copper(II) iodide give cuprous iodide and iodine.[34]

- 2 Cu2+ + 4 I− → 2 CuI + I2

Coordination chemistry

-sulfat-Monohydrat_Kristalle.png)

Copper, like all metals, forms coordination complexes with ligands. In aqueous solution, copper(II) exists as [Cu(H2O)6]2+. This complex exhibits the fastest water exchange rate (speed of water ligands attaching and detaching) for any transition metal aquo complex. Adding aqueous sodium hydroxide causes the precipitation of light blue solid copper(II) hydroxide. A simplified equation is:

- Cu2+ + 2 OH− → Cu(OH)2

Aqueous ammonia results in the same precipitate. Upon adding excess ammonia, the precipitate dissolves, forming tetraamminecopper(II):

- Cu(H2O)4(OH)2 + 4 NH3 → [Cu(H2O)2(NH3)4]2+ + 2 H2O + 2 OH−

Many other oxyanions form complexes; these include copper(II) acetate, copper(II) nitrate, and copper(II) carbonate. Copper(II) sulfate forms a blue crystalline pentahydrate, which is the most familiar copper compound in the laboratory. It is used in a fungicide called the Bordeaux mixture.[35]

-3D-balls.png)

Polyols, compounds containing more than one alcohol functional group, generally interact with cupric salts. For example, copper salts are used to test for reducing sugars. Specifically, using Benedict's reagent and Fehling's solution the presence of the sugar is signaled by a color change from blue Cu(II) to reddish copper(I) oxide.[36] Schweizer's reagent and related complexes with ethylenediamine and other amines dissolve cellulose.[37] Amino acids form very stable chelate complexes with copper(II). Many wet-chemical tests for copper ions exist, one involving potassium ferrocyanide, which gives a brown precipitate with copper(II) salts.

Organocopper chemistry

Compounds that contain a carbon-copper bond are known as organocopper compounds. They are very reactive towards oxygen to form copper(I) oxide and have many uses in chemistry. They are synthesized by treating copper(I) compounds with Grignard reagents, terminal alkynes or organolithium reagents;[38] in particular, the last reaction described produces a Gilman reagent. These can undergo substitution with alkyl halides to form coupling products; as such, they are important in the field of organic synthesis. Copper(I) acetylide is highly shock-sensitive but is an intermediate in reactions such as the Cadiot-Chodkiewicz coupling[39] and the Sonogashira coupling.[40] Conjugate addition to enones[41] and carbocupration of alkynes[42] can also be achieved with organocopper compounds. Copper(I) forms a variety of weak complexes with alkenes and carbon monoxide, especially in the presence of amine ligands.[43]

Copper(III) and copper(IV)

Copper(III) is most characteristically found in oxides. A simple example is potassium cuprate, KCuO2, a blue-black solid.[44] The best studied copper(III) compounds are the cuprate superconductors. Yttrium barium copper oxide (YBa2Cu3O7) consists of both Cu(II) and Cu(III) centres. Like oxide, fluoride is a highly basic anion[45] and is known to stabilize metal ions in high oxidation states. Indeed, both copper(III) and even copper(IV) fluorides are known, K3CuF6 and Cs2CuF6, respectively.[34]

Some copper proteins form oxo complexes, which also feature copper(III).[46] With tetrapeptides, purple-colored copper(III) complexes are stabilized by the deprotonated amide ligands.[47]

Complexes of copper(III) are also observed as intermediates in reactions of organocopper compounds.

History

Copper Age

Copper occurs naturally as native copper and was known to some of the oldest civilizations on record. It has a history of use that is at least 10,000 years old, and estimates of its discovery place it at 9000 BC in the Middle East;[48] a copper pendant was found in northern Iraq that dates to 8700 BC.[49] There is evidence that gold and meteoric iron (but not iron smelting) were the only metals used by humans before copper.[50] The history of copper metallurgy is thought to have followed the following sequence: 1) cold working of native copper, 2) annealing, 3) smelting, and 4) the lost wax method. In southeastern Anatolia, all four of these metallurgical techniques appears more or less simultaneously at the beginning of the Neolithic c. 7500 BC.[51] However, just as agriculture was independently invented in several parts of the world, copper smelting was invented locally in several different places. It was probably discovered independently in China before 2800 BC, in Central America perhaps around 600 AD, and in West Africa about the 9th or 10th century AD.[52] Investment casting was invented in 4500–4000 BC in Southeast Asia[48] and carbon dating has established mining at Alderley Edge in Cheshire, UK at 2280 to 1890 BC.[53] Ötzi the Iceman, a male dated from 3300–3200 BC, was found with an axe with a copper head 99.7% pure; high levels of arsenic in his hair suggest his involvement in copper smelting.[54] Experience with copper has assisted the development of other metals; in particular, copper smelting led to the discovery of iron smelting.[54] Production in the Old Copper Complex in Michigan and Wisconsin is dated between 6000 and 3000 BC.[55][56] Natural bronze, a type of copper made from ores rich in silicon, arsenic, and (rarely) tin, came into general use in the Balkans around 5500 BC.

Bronze Age

Alloying copper with tin to make bronze was first practiced about 4000 years after the discovery of copper smelting, and about 2000 years after "natural bronze" had come into general use. Bronze artifacts from the Vinča culture date to 4500 BC.[57] Sumerian and Egyptian artifacts of copper and bronze alloys date to 3000 BC.[58] The Bronze Age began in Southeastern Europe around 3700–3300 BC, in Northwestern Europe about 2500 BC. It ended with the beginning of the Iron Age, 2000–1000 BC in the Near East, 600 BC in Northern Europe. The transition between the Neolithic period and the Bronze Age was formerly termed the Chalcolithic period (copper-stone), with copper tools being used with stone tools. This term has gradually fallen out of favor because in some parts of the world the Chalcolithic and Neolithic are coterminous at both ends. Brass, an alloy of copper and zinc, is of much more recent origin. It was known to the Greeks, but became a significant supplement to bronze during the Roman Empire.[58]

Antiquity and Middle Ages

In Greece, copper was known by the name chalkos (χαλκός). It was an important resource for the Romans, Greeks and other ancient peoples. In Roman times, it was known as aes Cyprium, aes being the generic Latin term for copper alloys and Cyprium from Cyprus, where much copper was mined. The phrase was simplified to cuprum, hence the English copper. Aphrodite and Venus represented copper in mythology and alchemy, because of its lustrous beauty, its ancient use in producing mirrors, and its association with Cyprus, which was sacred to the goddess. The seven heavenly bodies known to the ancients were associated with the seven metals known in antiquity, and Venus was assigned to copper.[59]

Britain's first use of brass occurred around the 3rd–2nd century BC. In North America, copper mining began with marginal workings by Native Americans. Native copper is known to have been extracted from sites on Isle Royale with primitive stone tools between 800 and 1600.[60] Copper metallurgy was flourishing in South America, particularly in Peru around 1000 AD; it proceeded at a much slower rate on other continents. Copper burial ornamentals from the 15th century have been uncovered, but the metal's commercial production did not start until the early 20th century.

The cultural role of copper has been important, particularly in currency. Romans in the 6th through 3rd centuries BC used copper lumps as money. At first, the copper itself was valued, but gradually the shape and look of the copper became more important. Julius Caesar had his own coins made from brass, while Octavianus Augustus Caesar's coins were made from Cu-Pb-Sn alloys. With an estimated annual output of around 15,000 t, Roman copper mining and smelting activities reached a scale unsurpassed until the time of the Industrial Revolution; the provinces most intensely mined were those of Hispania, Cyprus and in Central Europe.[61][62]

The gates of the Temple of Jerusalem used Corinthian bronze made by depletion gilding. It was most prevalent in Alexandria, where alchemy is thought to have begun.[63] In ancient India, copper was used in the holistic medical science Ayurveda for surgical instruments and other medical equipment. Ancient Egyptians (~2400 BC) used copper for sterilizing wounds and drinking water, and later on for headaches, burns, and itching. The Baghdad Battery, with copper cylinders soldered to lead, dates back to 248 BC to AD 226 and resembles a galvanic cell, leading people to believe this was the first battery; the claim has not been verified.[64]

Modern period

The Great Copper Mountain was a mine in Falun, Sweden, that operated from the 10th century to 1992. It produced two thirds of Europe's copper demand in the 17th century and helped fund many of Sweden's wars during that time.[65] It was referred to as the nation's treasury; Sweden had a copper backed currency.[66]

The uses of copper in art were not limited to currency: it was used by Renaissance sculptors, in photographic technology known as the daguerreotype, and the Statue of Liberty. Copper plating and copper sheathing for ships' hulls was widespread; the ships of Christopher Columbus were among the earliest to have this feature.[67] The Norddeutsche Affinerie in Hamburg was the first modern electroplating plant starting its production in 1876.[68] The German scientist Gottfried Osann invented powder metallurgy in 1830 while determining the metal's atomic mass; around then it was discovered that the amount and type of alloying element (e.g., tin) to copper would affect bell tones. Flash smelting was developed by Outokumpu in Finland and first applied at Harjavalta in 1949; the energy-efficient process accounts for 50% of the world's primary copper production.[69]

The Intergovernmental Council of Copper Exporting Countries, formed in 1967 with Chile, Peru, Zaire and Zambia, played a similar role for copper as OPEC does for oil. It never achieved the same influence, particularly because the second-largest producer, the United States, was never a member; it was dissolved in 1988.[70]

Applications

The major applications of copper are in electrical wires (60%), roofing and plumbing (20%) and industrial machinery (15%). Copper is mostly used as a pure metal, but when a higher hardness is required it is combined with other elements to make an alloy (5% of total use) such as brass and bronze.[18] A small part of copper supply is used in production of compounds for nutritional supplements and fungicides in agriculture.[35][71] Machining of copper is possible, although it is usually necessary to use an alloy for intricate parts to get good machinability characteristics.

Wire and cable

Despite competition from other materials, copper remains the preferred electrical conductor in nearly all categories of electrical wiring with the major exception being overhead electric power transmission where aluminium is often preferred.[72][73] Copper wire is used in power generation, power transmission, power distribution, telecommunications, electronics circuitry, and countless types of electrical equipment.[74] Electrical wiring is the most important market for the copper industry.[75] This includes building wire, communications cable, power distribution cable, appliance wire, automotive wire and cable, and magnet wire. Roughly half of all copper mined is used to manufacture electrical wire and cable conductors.[76] Many electrical devices rely on copper wiring because of its multitude of inherent beneficial properties, such as its high electrical conductivity, tensile strength, ductility, creep (deformation) resistance, corrosion resistance, low thermal expansion, high thermal conductivity, solderability, and ease of installation.

Electronics and related devices

Integrated circuits and printed circuit boards increasingly feature copper in place of aluminium because of its superior electrical conductivity (see Copper interconnect for main article); heat sinks and heat exchangers use copper as a result of its superior heat dissipation capacity to aluminium. Electromagnets, vacuum tubes, cathode ray tubes, and magnetrons in microwave ovens use copper, as do wave guides for microwave radiation.[77]

Electric motors

Copper's greater conductivity versus other metals enhances the electrical energy efficiency of motors.[78] This is important because motors and motor-driven systems account for 43%-46% of all global electricity consumption and 69% of all electricity used by industry.[79] Increasing the mass and cross section of copper in a coil increases the electrical energy efficiency of the motor. Copper motor rotors, a new technology designed for motor applications where energy savings are prime design objectives,[80][81] are enabling general-purpose induction motors to meet and exceed National Electrical Manufacturers Association (NEMA) premium efficiency standards.[82]

Architecture

Copper has been used since ancient times as a durable, corrosion resistant, and weatherproof architectural material.[83][84][85][86] Roofs, flashings, rain gutters, downspouts, domes, spires, vaults, and doors have been made from copper for hundreds or thousands of years. Copper's architectural use has been expanded in modern times to include interior and exterior wall cladding, building expansion joints, radio frequency shielding, and antimicrobial indoor products, such as attractive handrails, bathroom fixtures, and counter tops. Some of copper's other important benefits as an architectural material include its low thermal movement, light weight, lightning protection, and its recyclability.

The metal's distinctive natural green patina has long been coveted by architects and designers. The final patina is a particularly durable layer that is highly resistant to atmospheric corrosion, thereby protecting the underlying metal against further weathering.[87][88][89] It can be a mixture of carbonate and sulfate compounds in various amounts, depending upon environmental conditions such as sulfur-containing acid rain.[90][91][92][93] Architectural copper and its alloys can also be 'finished' to embark a particular look, feel, and/or color. Finishes include mechanical surface treatments, chemical coloring, and coatings.[94]

Copper has excellent brazing and soldering properties and can be welded; the best results are obtained with gas metal arc welding.[95]

Antibiofouling applications

Copper is biostatic, meaning bacteria will not grow on it. For this reason it has long been used to line parts of ships to protect against barnacles and mussels. It was originally used pure, but has since been superseded by Muntz metal. Similarly, as discussed in copper alloys in aquaculture, copper alloys have become important netting materials in the aquaculture industry because they are antimicrobial and prevent biofouling, even in extreme conditions[96] and have strong structural and corrosion-resistant[97] properties in marine environments.

Antimicrobial applications

Numerous antimicrobial efficacy studies have been conducted in the past 10 years regarding copper's efficacy to destroy a wide range of bacteria, as well as influenza A virus, adenovirus, and fungi.[98]

Copper-alloy touch surfaces have natural intrinsic properties to destroy a wide range of microorganisms (e.g., E. coli O157:H7, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Staphylococcus, Clostridium difficile, influenza A virus, adenovirus, and fungi).[98] Some 355 copper alloys were proven to kill more than 99.9% of disease-causing bacteria within just two hours when cleaned regularly.[99] The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has approved the registrations of these copper alloys as "antimicrobial materials with public health benefits,"[99] which allows manufacturers to legally make claims as to the positive public health benefits of products made with registered antimicrobial copper alloys. In addition, the EPA has approved a long list of antimicrobial copper products made from these alloys, such as bedrails, handrails, over-bed tables, sinks, faucets, door knobs, toilet hardware, computer keyboards, health club equipment, shopping cart handles, etc. (for a comprehensive list of products, see: Antimicrobial copper-alloy touch surfaces#Approved products). Copper doorknobs are used by hospitals to reduce the transfer of disease, and Legionnaires' disease is suppressed by copper tubing in plumbing systems.[100] Antimicrobial copper alloy products are now being installed in healthcare facilities in the U.K., Ireland, Japan, Korea, France, Denmark, and Brazil and in the subway transit system in Santiago, Chile, where copper-zinc alloy handrails will be installed in some 30 stations between 2011–2014.[101][102][103]

Folk medicine

Copper is commonly used in jewelry, and folklore says that copper bracelets relieve arthritis symptoms.[104] In alternative medicine, some proponents speculate that excess copper absorbed through the skin can treat some ailments, or that the copper somehow creates a magnetic field, treating nearby tissue.

In various studies, though, no difference is found between arthritis treated with a copper bracelet, magnetic bracelet, or placebo bracelet.[105][106] As far as medical science is concerned, wearing copper has no known benefit, for any medical condition at all. A human being can have a dietary copper deficiency, but this is very rare, because copper is present in many common foods, including legumes (beans), grains, and nuts. [107]

There is no evidence that copper even can be absorbed through the skin. But if it were, this could actually lead to copper poisoning, which may actually be more likely than beneficial effects.[108]

Compression clothing

More recently, some compression clothing has been sold with copper woven into it, with the same folk medicine claims being made. While compression clothing is a real treatment for some ailments, therefore the clothing may appear to work, the added copper may very well have no benefit beyond a placebo effect.[109]

Other uses

Copper compounds in liquid form are used as a wood preservative, particularly in treating original portion of structures during restoration of damage due to dry rot. Together with zinc, copper wires may be placed over non-conductive roofing materials to discourage the growth of moss. Textile fibers use copper to create antimicrobial protective fabrics,[110][111] as do ceramic glazes, stained glass and musical instruments. Electroplating commonly uses copper as a base for other metals such as nickel.

Copper is one of three metals, along with lead and silver, used in a museum materials testing procedure called the Oddy test. In this procedure, copper is used to detect chlorides, oxides, and sulfur compounds.

Copper is used as the printing plate in etching, engraving and other forms of intaglio (printmaking) printmaking.

Copper oxide and carbonate is used in glassmaking and in ceramic glazes to impart green and brown colors.

Copper is the principal alloying metal in some sterling silver and gold alloys. It may also be used on its own, or as a constituent of brass, bronze, gilding metal and many other base metal alloys.

Degradation

Chromobacterium violaceum and Pseudomonas fluorescens can both mobilize solid copper, as a cyanide compound.[112] The ericoid mycorrhizal fungi associated with Calluna, Erica and Vaccinium can grow in copper metalliferous soils.[112] The ectomycorrhizal fungus Suillus luteus protects young pine trees from copper toxicity. A sample of the fungus Aspergillus niger was found growing from gold mining solution; and was found to contain cyano metal complexes; such as gold, silver, copper iron and zinc. The fungus also plays a role in the solubilization of heavy metal sulfides.[113]

Biological role

Copper proteins have diverse roles in biological electron transport and oxygen transportation, processes that exploit the easy interconversion of Cu(I) and Cu(II).[114][115][116] [117] The biological role for copper commenced with the appearance of oxygen in earth's atmosphere.[118]

Copper is essential in the aerobic respiration of all eukaryotes. In mitochondria it is found in cytochrome c oxidase, which is the last protein in oxidative phosphorylation. Cytochrome c oxidase is the protein which binds the O2 between a copper and an iron, transferring 8 electrons to the O2 to reduce it to two molecules of water.

Copper is also found in many superoxide dismutases, proteins that catalyze the decomposition of superoxides, by converting it (by disproportionation) to oxygen and hydrogen peroxide:

- 2 HO2 → H2O2 + O2

The protein hemocyanin is the oxygen carrier in most mollusks and some arthropods such as the horseshoe crab (Limulus polyphemus).[119] Because hemocyanin is blue, these organisms have blue blood, not the red blood found in organisms that rely on iron in hemoglobin for this purpose. Structurally related to hemocyanin are the laccases and tyrosinases. Instead of reversibly binding oxygen, these proteins hydroxylate substrates, illustrated by their role in the formation of lacquers.[117]

Several copper proteins, such as the "blue copper proteins", do not interact directly with substrates, hence they are not enzymes. These proteins relay electrons by the process called electron transfer.[117]

A unique tetranuclear copper center has been found in nitrous-oxide reductase.[120]

Dietary needs

Copper is an essential trace element in plants and animals, but not some microorganisms. The human body contains copper at a level of about 1.4 to 2.1 mg per kg of body mass.[121] Stated differently, the RDA for copper in normal healthy adults is quoted as 0.97 mg/day and as 3.0 mg/day.[122] Copper is absorbed in the gut, then transported to the liver bound to albumin.[123] After processing in the liver, copper is distributed to other tissues in a second phase. Copper transport here involves the protein ceruloplasmin, which carries the majority of copper in blood. Ceruloplasmin also carries copper that is excreted in milk, and is particularly well-absorbed as a copper source.[124] Copper in the body normally undergoes enterohepatic circulation (about 5 mg a day, vs. about 1 mg per day absorbed in the diet and excreted from the body), and the body is able to excrete some excess copper, if needed, via bile, which carries some copper out of the liver that is not then reabsorbed by the intestine.[125][126]

Copper-based disorders

Because of its role in facilitating iron uptake, copper deficiency can produce anemia-like symptoms, neutropenia, bone abnormalities, hypopigmentation, impaired growth, increased incidence of infections, osteoporosis, hyperthyroidism, and abnormalities in glucose and cholesterol metabolism. Conversely, Wilson's disease causes an accumulation of copper in body tissues.

Severe deficiency can be found by testing for low plasma or serum copper levels, low ceruloplasmin, and low red blood cell superoxide dismutase levels; these are not sensitive to marginal copper status. The "cytochrome c oxidase activity of leucocytes and platelets" has been stated as another factor in deficiency, but the results have not been confirmed by replication.[127]

| NFPA 704 "fire diamond" |

|---|

| Fire diamond for copper metal |

Gram quantities of various copper salts have been taken in suicide attempts and produced acute copper toxicity in humans, possibly due to redox cycling and the generation of reactive oxygen species that damage DNA.[128][129] Corresponding amounts of copper salts (30 mg/kg) are toxic in animals.[130] A minimum dietary value for healthy growth in rabbits has been reported to be at least 3 ppm in the diet.[131] However, higher concentrations of copper (100 ppm, 200 ppm, or 500 ppm) in the diet of rabbits may favorably influence feed conversion efficiency, growth rates, and carcass dressing percentages.[132]

Chronic copper toxicity does not normally occur in humans because of transport systems that regulate absorption and excretion. Autosomal recessive mutations in copper transport proteins can disable these systems, leading to Wilson's disease with copper accumulation and cirrhosis of the liver in persons who have inherited two defective genes.[121]

Elevated copper levels have also been linked to worsening symptoms of Alzheimer's disease.[133][134]

Occupational exposure

In the US, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has designated a permissible exposure limit (PEL) for copper dust and fumes in the workplace as a time-weighted average (TWA) of 1 mg/m3. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has set a Recommended exposure limit (REL) of 1 mg/m3, time-weighted average. The IDLH (immediately dangerous to life and health) value is 100 mg/m3.[135]

See also

- Electroplating

- Erosion corrosion of copper water tubes

- Metal theft

- Smelter

- Peak copper

- Category:Copper mining companies

References

- ↑ Standard Atomic Weights 2013. Commission on Isotopic Abundances and Atomic Weights

- ↑ Lide, D. R., ed. (2005). "Magnetic susceptibility of the elements and inorganic compounds". CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (PDF) (86th ed.). Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0486-5.

- ↑ McHenry, Charles, ed. (1992). The New Encyclopedia Britannica 3 (15 ed.). Chicago: Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc. p. 612. ISBN 085-229553-7.

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th ed., vol. 7, p. 102.

- ↑ Johnson, MD PhD, Larry E., ed. (2008). "Copper". Merck Manual Home Health Handbook. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- 1 2 3 George L. Trigg; Edmund H. Immergut (1 November 1992). Encyclopedia of applied physics. 4: Combustion to Diamagnetism. VCH Publishers. pp. 267–272. ISBN 978-3-527-28126-8. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ↑ Smith, William F. & Hashemi, Javad (2003). Foundations of Materials Science and Engineering. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 223. ISBN 0-07-292194-3.

- 1 2 3 Hammond, C. R. (2004). The Elements, in Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (81st ed.). CRC press. ISBN 0-8493-0485-7.

- ↑ Resistance Welding Manufacturing Alliance (2003). Resistance Welding Manual (4th ed.). Resistance Welding Manufacturing Alliance. pp. 18–12. ISBN 0-9624382-0-0.

- ↑ "Galvanic Corrosion". Corrosion Doctors. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- ↑ Chambers, William; Chambers, Robert (1884). Chambers's Information for the People L (5th ed.). W. & R. Chambers. p. 312. ISBN 0-665-46912-8.

- ↑ "Copper.org: Education: Statue of Liberty: Reclothing the First Lady of Metals – Repair Concerns". Copper.org. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ↑ Rickett, B. I.; Payer, J. H. (1995). "Composition of Copper Tarnish Products Formed in Moist Air with Trace Levels of Pollutant Gas: Hydrogen Sulfide and Sulfur Dioxide/Hydrogen Sulfide". Journal of the Electrochemical Society 142 (11): 3723–3728. doi:10.1149/1.2048404.

- 1 2 Audi, G; Bersillon, O.; Blachot, J.; Wapstra, A.H. (2003). "Nubase2003 Evaluation of Nuclear and Decay Properties". Nuclear Physics A (Atomic Mass Data Center) 729: 3. Bibcode:2003NuPhA.729....3A. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2003.11.001.

- ↑ "Interactive Chart of Nuclides". National Nuclear Data Center. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ↑ Okazawad, Hidehiko; Yonekura, Yoshiharu; Fujibayashi, Yasuhisa; Nishizawa, Sadahiko; Magata, Yasuhiro; Ishizu, Koichi; Tanaka, Fumiko; Tsuchida, Tatsuro; Tamaki, Nagara; Konishi, Junji (1994). "Clinical Application and Quantitative Evaluation of Generator-Produced Copper-62-PTSM as a Brain Perfusion Tracer for PET" (PDF). Journal of Nuclear Medicine 35 (12): 1910–1915. PMID 7989968.

- ↑ Romano, Donatella; Matteucci, Fransesca (2007). "Contrasting copper evolution in ω Centauri and the Milky Way". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters 378 (1): L59–L63. arXiv:astro-ph/0703760. Bibcode:2007MNRAS.378L..59R. doi:10.1111/j.1745-3933.2007.00320.x.

- 1 2 3 4 Emsley, John (11 August 2003). Nature's building blocks: an A-Z guide to the elements. Oxford University Press. pp. 121–125. ISBN 978-0-19-850340-8. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ↑ Rickwood, P. C. (1981). "The largest crystals" (PDF). American Mineralogist 66: 885.

- ↑ Randazzo, Ryan (19 June 2011). "A new method to harvest copper". Azcentral.com. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- ↑ Gordon, R. B.; Bertram, M.; Graedel, T. E. (2006). "Metal stocks and sustainability". PNAS 103 (5): 1209–1214. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103.1209G. doi:10.1073/pnas.0509498103. PMC 1360560. PMID 16432205.

- 1 2 Leonard, Andrew (2 March 2006). "Peak copper?". Salon – How the World Works. Retrieved 23 March 2008.

- ↑ Brown, Lester (2006). Plan B 2.0: Rescuing a Planet Under Stress and a Civilization in Trouble. New York: W.W. Norton. p. 109. ISBN 0-393-32831-7.

- ↑ Schmitz, Christopher (1986). "The Rise of Big Business in the World, Copper Industry 1870–1930". Economic History Review. 2 39 (3): 392–410. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.1986.tb00411.x. JSTOR 2596347.

- ↑ "Copper Trends: Live Metal Spot Prices".

- ↑ Ackerman, R. (2 April 2009). "A Bottom In Sight For Copper". Forbes.

- 1 2 Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 0-08-037941-9.

- ↑ Watling, H. R. (2006). "The bioleaching of sulphide minerals with emphasis on copper sulphides — A review" (PDF). Hydrometallurgy 84 (1, 2): 81–108. doi:10.1016/j.hydromet.2006.05.001.

- ↑ Samans, Carl (1949). Engineering metals and their alloys. New York: Macmillan. OCLC 716492542.

- ↑ "International Copper Association".

- ↑ "Overview of Recycled Copper" Copper.org. Copper.org (25 August 2010). Retrieved on 8 November 2011.

- ↑ "Gold Jewellery Alloys". World Gold Council. Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- ↑ Balver Zinn Solder Sn97Cu3. (PDF) . balverzinn.com. Retrieved on 8 November 2011.

- 1 2 3 Holleman, A. F.; Wiberg, N. (2001). Inorganic Chemistry. San Diego: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-352651-9.

- 1 2 Wiley-Vch (2 April 2007). "Nonsystematic (Contact) Fungicides". Ullmann's Agrochemicals. p. 623. ISBN 978-3-527-31604-5.

- ↑ Ralph L. Shriner, Christine K. F. Hermann, Terence C. Morrill, David Y. Curtin, Reynold C. Fuson "The Systematic Identification of Organic Compounds" 8th edition, J. Wiley, Hoboken. ISBN 0-471-21503-1

- ↑ Kay Saalwächter, Walther Burchard, Peter Klüfers, G. Kettenbach, and Peter Mayer, Dieter Klemm, Saran Dugarmaa "Cellulose Solutions in Water Containing Metal Complexes" Macromolecules 2000, 33, 4094–4107. doi:10.1021/ma991893m

- ↑ "Modern Organocopper Chemistry" Norbert Krause, Ed., Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2002. ISBN 978-3-527-29773-3.

- ↑ Berná, José; Goldup, Stephen; Lee, Ai-Lan; Leigh, David; Symes, Mark; Teobaldi, Gilberto; Zerbetto, Fransesco (26 May 2008). "Cadiot–Chodkiewicz Active Template Synthesis of Rotaxanes and Switchable Molecular Shuttles with Weak Intercomponent Interactions". Angewandte Chemie 120 (23): 4464–4468. doi:10.1002/ange.200800891.

- ↑ Rafael Chinchilla & Carmen Nájera (2007). "The Sonogashira Reaction: A Booming Methodology in Synthetic Organic Chemistry". Chemical Reviews 107 (3): 874–922. doi:10.1021/cr050992x. PMID 17305399.

- ↑ "An Addition of an Ethylcopper Complex to 1-Octyne: (E)-5-Ethyl-1,4-Undecadiene" (PDF). Organic Syntheses 64: 1. 1986. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.064.0001.

- ↑ Kharasch, M. S.; Tawney, P. O. (1941). "Factors Determining the Course and Mechanisms of Grignard Reactions. II. The Effect of Metallic Compounds on the Reaction between Isophorone and Methylmagnesium Bromide". Journal of the American Chemical Society 63 (9): 2308–2316. doi:10.1021/ja01854a005.

- ↑ Imai, Sadako; Fujisawa, Kiyoshi; Kobayashi, Takako; Shirasawa, Nobuhiko; Fujii, Hiroshi; Yoshimura, Tetsuhiko; Kitajima, Nobumasa; Moro-oka, Yoshihiko (1998). "63Cu NMR Study of Copper(I) Carbonyl Complexes with Various Hydrotris(pyrazolyl)borates: Correlation between 63Cu Chemical Shifts and CO Stretching Vibrations". Inorg. Chem. 37 (12): 3066–3070. doi:10.1021/ic970138r.

- ↑ G. Brauer, ed. (1963). "Potassium Cuprate (III)". Handbook of Preparative Inorganic Chemistry 1 (2nd ed.). NY: Academic Press. p. 1015.

- ↑ Schwesinger, Reinhard; Link, Reinhard; Wenzl, Peter; Kossek, Sebastian (2006). "Anhydrous phosphazenium fluorides as sources for extremely reactive fluoride ions in solution". Chemistry – A European Journal 12 (2): 438. doi:10.1002/chem.200500838.

- ↑ Lewis, E. A.; Tolman, W. B. (2004). "Reactivity of Dioxygen-Copper Systems". Chemical Reviews 104 (2): 1047–1076. doi:10.1021/cr020633r. PMID 14871149.

- ↑ McDonald, M. R.; Fredericks, F. C.; Margerum, D. W. (1997). "Characterization of Copper(III)-Tetrapeptide Complexes with Histidine as the Third Residue". Inorganic Chemistry 36 (14): 3119–3124. doi:10.1021/ic9608713. PMID 11669966.

- 1 2 "CSA – Discovery Guides, A Brief History of Copper". Csa.com. Retrieved 12 September 2008.

- ↑ Rayner W. Hesse (2007). Jewelrymaking through History: an Encyclopedia. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 56. ISBN 0-313-33507-9.No primary source is given in that book.

- ↑ "Copper". Elements.vanderkrogt.net. Retrieved 12 September 2008.

- ↑ Renfrew, Colin (1990). Before civilization: the radiocarbon revolution and prehistoric Europe. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-013642-5. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ↑ Cowen, R. "Essays on Geology, History, and People". Retrieved 7 July 2009.

|chapter=ignored (help) - ↑ Timberlake, S. & Prag A.J.N.W. (2005). The Archaeology of Alderley Edge: Survey, excavation and experiment in an ancient mining landscape. Oxford: John and Erica Hedges Ltd. p. 396.

- 1 2 "CSA – Discovery Guides, A Brief History of Copper". CSA Discovery Guides. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- ↑ Pleger, Thomas C. "A Brief Introduction to the Old Copper Complex of the Western Great Lakes: 4000–1000 BC", Proceedings of the Twenty-seventh Annual Meeting of the Forest History Association of Wisconsin, Oconto, Wisconsin, 5 October 2002, pp. 10–18.

- ↑ Emerson, Thomas E. and McElrath, Dale L. Archaic Societies: Diversity and Complexity Across the Midcontinent, SUNY Press, 2009 ISBN 1-4384-2701-8.

- ↑ Radivojević, Miljana; Rehren, Thilo (December 2013). "Tainted ores and the rise of tin bronzes in Eurasia, c. 6500 years ago". Antiquity Publications Ltd.

- 1 2 McNeil, Ian (2002). Encyclopaedia of the History of Technology. London ; New York: Routledge. pp. 13, 48–66. ISBN 0-203-19211-7.

- ↑ Rickard, T. A. (1932). "The Nomenclature of Copper and its Alloys". Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (Royal Anthropological Institute) 62: 281. doi:10.2307/2843960. JSTOR 2843960.

- ↑ Martin, Susan R. (1995). "The State of Our Knowledge About Ancient Copper Mining in Michigan". The Michigan Archaeologist 41 (2–3): 119.

- ↑ Hong, S.; Candelone, J.-P.; Patterson, C. C.; Boutron, C. F. (1996). "History of Ancient Copper Smelting Pollution During Roman and Medieval Times Recorded in Greenland Ice". Science 272 (5259): 246–249 (247f.). Bibcode:1996Sci...272..246H. doi:10.1126/science.272.5259.246.

- ↑ de Callataÿ, François (2005). "The Graeco-Roman Economy in the Super Long-Run: Lead, Copper, and Shipwrecks". Journal of Roman Archaeology 18: 361–372 (366–369).

- ↑ Savenije, Tom J.; Warman, John M.; Barentsen, Helma M.; van Dijk, Marinus; Zuilhof, Han; Sudhölter, Ernst J. R. (2000). "Corinthian Bronze and the Gold of the Alchemists" (PDF). Macromolecules 33 (2): 60. Bibcode:2000MaMol..33...60S. doi:10.1021/ma9904870.

- ↑ "World Mysteries – Strange Artifacts, Baghdad Battery". World-Mysteries.com. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- ↑ Lynch, Martin (15 April 2004). Mining in World History. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-86189-173-0.

- ↑ "Gold: prices, facts, figures and research: A brief history of money". Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- ↑ "Copper History". Retrieved 4 September 2008.

- ↑ Stelter, M.; Bombach, H. (2004). "Process Optimization in Copper Electrorefining". Advanced Engineering Materials 6 (7): 558. doi:10.1002/adem.200400403.

- ↑ "Outokumpu Flash Smelting" (PDF). Outokumpu. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2011.

- ↑ Karen A. Mingst (1976). "Cooperation or illusion: an examination of the intergovernmental council of copper exporting countries". International Organization 30 (2): 263–287. doi:10.1017/S0020818300018270.

- ↑ "Copper". American Elements. 2008. Retrieved 12 July 2008.

- ↑ Pops, Horace, 2008, Processing of wire from antiquity to the future, Wire Journal International, June, pp 58–66

- ↑ The Metallurgy of Copper Wire, http://www.litz-wire.com/pdf%20files/Metallurgy_Copper_Wire.pdf

- ↑ Joseph, Günter, 1999, Copper: Its Trade, Manufacture, Use, and Environmental Status, edited by Kundig, Konrad J.A., ASM International, pps. 141–192 and pps. 331–375.

- ↑ "Copper, Chemical Element – Overview, Discovery and naming, Physical properties, Chemical properties, Occurrence in nature, Isotopes". Chemistryexplained.com. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ↑ Joseph, Günter, 1999, Copper: Its Trade, Manufacture, Use, and Environmental Status, edited by Kundig, Konrad J.A., ASM International, p.348

- ↑ "Accelerator: Waveguides (SLAC VVC)". SLAC Virtual Visitor Center. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- ↑ IE3 energy-saving motors, Engineer Live, http://www.engineerlive.com/Design-Engineer/Motors_and_Drives/IE3_energy-saving_motors/22687/

- ↑ Energy‐efficiency policy opportunities for electric motor‐driven systems, International Energy Agency, 2011 Working Paper in the Energy Efficiency Series, by Paul Waide and Conrad U. Brunner, OECD/IEA 2011

- ↑ Fuchsloch, J. and E.F. Brush, (2007), "Systematic Design Approach for a New Series of Ultra‐NEMA Premium Copper Rotor Motors", in EEMODS 2007 Conference Proceedings, 10‐15 June,Beijing.

- ↑ Copper motor rotor project; Copper Development Association; http://www.copper.org/applications/electrical/motor-rotor

- ↑ NEMA Premium Motors, The Association of Electrical Equipment and Medical Imaging Manufacturers; http://www.nema.org/gov/energy/efficiency/premium/

- ↑ Seale, Wayne (2007). The role of copper, brass, and bronze in architecture and design; Metal Architecture, May 2007

- ↑ Copper roofing in detail; Copper in Architecture; Copper Development Association, U.K., www.cda.org.uk/arch

- ↑ Architecture, European Copper Institute; http://eurocopper.org/copper/copper-architecture.html

- ↑ Kronborg completed; Agency for Palaces and Cultural Properties, København, http://www.slke.dk/en/slotteoghaver/slotte/kronborg/kronborgshistorie/kronborgfaerdigbygget.aspx?highlight=copper

- ↑ Berg, Jan. "Why did we paint the library's roof?". Archived from the original on 25 June 2007. Retrieved 20 September 2007.

- ↑ Architectural considerations; Copper in Architecture Design Handbook, http://www.copper.org/applications/architecture/arch_dhb/fundamentals/arch_considerations.htm

- ↑ Peters, Larry E. (2004). Preventing corrosion on copper roofing systems; Professional Roofing, October 2004, http://www.professionalroofing.net

- ↑ Oxidation Reaction: Why is the Statue of Liberty Blue-Green? Engage Students in Engineering; www.EngageEngineering.org; Chun Wu, Ph.D., Mount Marty College; Funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) under Grant No. 083306. http://www.wepanknowledgecenter.org/c/document_library/get_file?folderId=517&name=DLFE-2454.pdf

- ↑ Fitzgerald, K.P.; Nairn, J.; Atrens, A. (1998). "The chemistry of copper patination". Corrosion Science 40 (12): 2029–50. doi:10.1016/S0010-938X(98)00093-6.

- ↑ Application Areas: Architecture – Finishes – patina; http://www.copper.org/applications/architecture/finishes.html

- ↑ Glossary of copper terms, Copper Development Association (UK): http://www.copperinfo.co.uk/resources/glossary.shtml

- ↑ Finishes – natural weathering; Copper in Architecture Design Handbook, Copper Development Association Inc., http://www.copper.org/applications/architecture/arch_dhb/finishes/finishes.html

- ↑ Davis, Joseph R. (2001). Copper and Copper Alloys. ASM International. pp. 3–6, 266. ISBN 0-87170-726-8.

- ↑ Edding, Mario E., Flores, Hector, and Miranda, Claudio, (1995), Experimental Usage of Copper-Nickel Alloy Mesh in Mariculture. Part 1: Feasibility of usage in a temperate zone; Part 2: Demonstration of usage in a cold zone; Final report to the International Copper Association Ltd.

- ↑ Corrosion Behaviour of Copper Alloys used in Marine Aquaculture. (PDF) . copper.org. Retrieved on 8 November 2011.

- 1 2 Copper Touch Surfaces. Copper Touch Surfaces. Retrieved on 8 November 2011.

- 1 2 EPA registers copper-containing alloy products, May 2008

- ↑ Biurrun, Amaya; Caballero, Luis; Pelaz, Carmen; León, Elena; Gago, Alberto (1999). "Treatment of a Legionella pneumophila‐Colonized Water Distribution System Using Copper‐Silver Ionization and Continuous Chlorination". Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology 20 (6): 426–428. doi:10.1086/501645. JSTOR 30141645. PMID 10395146.

- ↑ Chilean subway protected with Antimicrobial Copper – Rail News from. rail.co. Retrieved on 8 November 2011.

- ↑ Codelco to provide antimicrobial copper for new metro lines (Chile). Construpages.com.ve. Retrieved on 8 November 2011.

- ↑ PR 811 Chilean Subway Installs Antimicrobial Copper. (PDF). antimicrobialcopper.com. Retrieved on 8 November 2011.

- ↑ Walker, WR; Keats, DM (1976). "An investigation of the therapeutic value of the 'copper bracelet'-dermal assimilation of copper in arthritic/rheumatoid conditions". Agents and actions 6 (4): 454–9. PMID 961545.

- ↑ The Daily Mail:

Copper bracelet arthritis cure is a myth, say scientists - ↑ National Institutes of Health (NIH):

PubMed

No difference was observed between devices in terms of their effects on pain as measured by the primary outcome measure (WOMAC A), the PRI and the VAS. Similar results were obtained for stiffness (WOMAC B), physical function (WOMAC C), and medication use. Further analyses of the PRI subscales revealed a statistically significant difference between devices (P=0.025), which favoured the experimental device. Participants reported lower sensory pain after wearing the standard magnetic wrist strap, than when wearing control devices. However, no adjustment was made for multiple testing. - ↑ University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences:

Can wearing a copper bracelet cure arthritis?

According to the Center for Hand and Upper Extremity Surgery at UAMS, copper deficiency is extremely rare and most regular diets provide enough copper to meet the daily requirements. Copper is a component of some of the normal cellular enzymes in most mineral rich foods, such as vegetables, potatoes, legumes (beans and peas), nuts (peanuts and pecans), grains (wheat and rye) and fruits. Supplementation is only needed in patients with serious medical conditions that affect their gastrointestinal tract and impair their ability to absorb nutrients. - ↑ University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences:

Find the Truth Behind Medical Myths

While it's never been proven that copper can copper be absorbed through the skin by wearing a bracelet, research has shown that excessive copper can result in poisoning, causing vomiting and, in severe cases, liver damage. - ↑ Truth in Advertising

Tommie Copper

So it seems possible that copper-infused compression clothing could help you recover from a tough workout, and it's also possible it could have some anti-bacterial properties in clothes. But as for the claims in the infomercial about relieving joint pain and helping with everyday aches — any relief from copper-compression seems more likely to be a placebo effect than anything else. Think carefully before shelling out for Tommie Copper. - ↑ "Copper and Cupron". Cupron.

- ↑ Ergowear, Copper antimicrobial yarn technology used in male underwear

- 1 2 Geoffrey Michael Gadd (March 2010). "Metals, minerals and microbes: geomicrobiology and bioremediation". Microbiology 156 (3): 609–643. doi:10.1099/mic.0.037143-0. PMID 20019082.

- ↑ Harbhajan Singh (2006-11-17). Mycoremediation: Fungal Bioremediation. p. 509. ISBN 9780470050583.

- ↑ Vest, Katherine E.; Hashemi, Hayaa F.; Cobine, Paul A. (2013). "Chapter 13 The Copper Metallome in Eukaryotic Cells". In Banci, Lucia. Metallomics and the Cell. Metal Ions in Life Sciences 12. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-5561-10_12. ISBN 978-94-007-5560-4. electronic-book ISBN 978-94-007-5561-1 ISSN 1559-0836 electronic-ISSN 1868-0402

- ↑ Vest, Katherine E.; Hashemi, Hayaa F.; Cobine, Paul A. (2013). "Chapter 12 The Copper Metallome in Prokaryotic Cells". In Banci, Lucia. Metallomics and the Cell. Metal Ions in Life Sciences 12. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-5561-10_13. ISBN 978-94-007-5560-4. electronic-book ISBN 978-94-007-5561-1 ISSN 1559-0836 electronic-ISSN 1868-0402

- ↑ Yee, Gereon M.; Tolman, William B. (2015). "Chapter 5, Section 4 Dioxygen Activation by Copper Complexes". In Peter M.H. Kroneck and Martha E. Sosa Torres. Sustaining Life on Planet Earth: Metalloenzymes Mastering Dioxygen and Other Chewy Gases. Metal Ions in Life Sciences 15. Springer. pp. 175–192. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-12415-5_5.

- 1 2 3 S. J. Lippard, J. M. Berg "Principles of bioinorganic chemistry" University Science Books: Mill Valley, CA; 1994. ISBN 0-935702-73-3.

- ↑ Decker, H. & Terwilliger, N. (2000). "COPs and Robbers: Putative evolution of copper oxygen-binding proteins". Journal of Experimental Biology 203 (Pt 12): 1777–1782. PMID 10821735.

- ↑ "Fun facts". Horseshoe crab. University of Delaware. Retrieved 13 July 2008.

- ↑ Schneider, Lisa K.; Wüst, Anja; Pomowski, Anja; Zhang, Lin; Einsle, Oliver (2014). "Chapter 8. No Laughing Matter: The Unmaking of the Greenhouse Gas Dinitrogen Monoxide by Nitrous Oxide Reductase". In Peter M.H. Kroneck; Martha E. Sosa Torres. The Metal-Driven Biogeochemistry of Gaseous Compounds in the Environment. Metal Ions in Life Sciences 14. Springer. pp. 177–210. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-9269-1_8.

- 1 2 "Amount of copper in the normal human body, and other nutritional copper facts". Retrieved 3 April 2009.

- ↑ Copper. In: Recommended Dietary Allowances. Washington, D.C.: National Research Council, Food Nutrition Board, NRC/NAS. 1980. pp. 151–154.

- ↑ Adelstein, S. J.; Vallee, B. L. (1961). "Copper metabolism in man". New England Journal of Medicine 265 (18): 892–897. doi:10.1056/NEJM196111022651806.

- ↑ M C Linder; Wooten, L; Cerveza, P; Cotton, S; Shulze, R; Lomeli, N (1 May 1998). "Copper transport". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 67 (5): 965S–971S. PMID 9587137.

- ↑ Frieden, E; Hsieh, HS (1976). "Ceruloplasmin: The copper transport protein with essential oxidase activity". Advances in enzymology and related areas of molecular biology. Advances in Enzymology - and Related Areas of Molecular Biology 44: 187–236. doi:10.1002/9780470122891.ch6. ISBN 9780470122891. JSTOR 20170553. PMID 775938.

- ↑ S. S. Percival; Harris, ED (1 January 1990). "Copper transport from ceruloplasmin: Characterization of the cellular uptake mechanism". American Journal of Physiology. Cell Physiology 258 (1): C140–6. PMID 2301561.

- ↑ Bonham, Maxine; O'Connor, Jacqueline M.; Hannigan, Bernadette M.; Strain, J. J. (2002). "The immune system as a physiological indicator of marginal copper status?". British Journal of Nutrition 87 (5): 393–403. doi:10.1079/BJN2002558. PMID 12010579.

- ↑ Li, Yunbo; Trush, Michael; Yager, James (1994). "DNA damage caused by reactive oxygen species originating from a copper-dependent oxidation of the 2-hydroxy catechol of estradiol". Carcinogenesis 15 (7): 1421–1427. doi:10.1093/carcin/15.7.1421. PMID 8033320.

- ↑ Gordon, Starkebaum; John, M. Harlan (April 1986). "Endothelial cell injury due to copper-catalyzed hydrogen peroxide generation from homocysteine". J. Clin. Invest. 77 (4): 1370–6. doi:10.1172/JCI112442. PMC 424498. PMID 3514679.

- ↑ "Pesticide Information Profile for Copper Sulfate". Cornell University. Retrieved 10 July 2008.

- ↑ Hunt, Charles E. & William W. Carlton (1965). "Cardiovascular Lesions Associated with Experimental Copper Deficiency in the Rabbit". Journal of Nutrition 87 (4): 385–394. PMID 5841854.

- ↑ Ayyat M.S.; Marai I.F.M.; Alazab A.M. (1995). "Copper-Protein Nutrition of New Zealand White Rabbits under Egyptian Conditions". World Rabbit Science 3 (3): 113–118. doi:10.4995/wrs.1995.249.

- ↑ Brewer GJ. Copper excess, zinc deficiency, and cognition loss in Alzheimer's disease. BioFactors (Oxford, England). March 2012;38(2):107–113. doi:10.1002/biof.1005. PMID 22438177.

- ↑ "Copper: Alzheimer's Disease". Examine.com. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- ↑ "NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards #0150". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

Notes

|

|

|

|

| in pure water, or acidic or alkali conditions. Copper in neutral water is more noble than hydrogen. | in water containing sulfide | in 10 M ammonia solution | in a chloride solution |

Further reading

- Massaro, Edward J., ed. (2002). Handbook of Copper Pharmacology and Toxicology. Humana Press. ISBN 0-89603-943-9.

- "Copper: Technology & Competitiveness (Summary) Chapter 6: Copper Production Technology" (PDF). Office of Technology Assessment. 2005.

- Current Medicinal Chemistry, Volume 12, Number 10, May 2005, pp. 1161–1208(48) Metals, Toxicity and Oxidative Stress

- William D. Callister (2003). Materials Science and Engineering: an Introduction (6th ed.). Wiley, New York. Table 6.1, p. 137. ISBN 0-471-73696-1.

- Material: Copper (Cu), bulk, MEMS and Nanotechnology Clearinghouse.

- Kim BE; Nevitt T; Thiele DJ (2008). "Mechanisms for copper acquisition, distribution and regulation". Nat. Chem. Biol. 4 (3): 176–85. doi:10.1038/nchembio.72. PMID 18277979.

- Copper transport disorders: an Instant insight from the Royal Society of Chemistry

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Copper |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Copper. |

| Look up copper in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Copper at The Periodic Table of Videos (University of Nottingham)

- National Pollutant Inventory – Copper and compounds fact sheet

- Copper Resource Page. Includes several PDF files detailing the material properties of various kinds of copper, as well as various guides and tools for the copper industry.

- CDC – NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards – Copper (dusts and mists)

- CDC – NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards – Copper fume

- The Copper Development Association has an extensive site of properties and uses of copper; it also maintains a web site dedicated to brass, a copper alloy.

- The Third Millennium Online page on Copper

- Price history of copper, according to the IMF

| Periodic table (Large cells) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | ||||||||||||||||

| 1 | H | He | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Li | Be | B | C | N | O | F | Ne | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | Na | Mg | Al | Si | P | S | Cl | Ar | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | K | Ca | Sc | Ti | V | Cr | Mn | Fe | Co | Ni | Cu | Zn | Ga | Ge | As | Se | Br | Kr | |||||||||||||||

| 5 | Rb | Sr | Y | Zr | Nb | Mo | Tc | Ru | Rh | Pd | Ag | Cd | In | Sn | Sb | Te | I | Xe | |||||||||||||||

| 6 | Cs | Ba | La | Ce | Pr | Nd | Pm | Sm | Eu | Gd | Tb | Dy | Ho | Er | Tm | Yb | Lu | Hf | Ta | W | Re | Os | Ir | Pt | Au | Hg | Tl | Pb | Bi | Po | At | Rn | |