Convex function

In mathematics, a real-valued function defined on an interval is called convex (or convex downward or concave upward) if the line segment between any two points on the graph of the function lies above or on the graph, in a Euclidean space (or more generally a vector space) of at least two dimensions. Equivalently, a function is convex if its epigraph (the set of points on or above the graph of the function) is a convex set. Well-known examples of convex functions are the quadratic function  and the exponential function

and the exponential function  for any real number x.

for any real number x.

Convex functions play an important role in many areas of mathematics. They are especially important in the study of optimization problems where they are distinguished by a number of convenient properties. For instance, a (strictly) convex function on an open set has no more than one minimum. Even in infinite-dimensional spaces, under suitable additional hypotheses, convex functions continue to satisfy such properties and, as a result, they are the most well-understood functionals in the calculus of variations. In probability theory, a convex function applied to the expected value of a random variable is always less than or equal to the expected value of the convex function of the random variable. This result, known as Jensen's inequality, underlies many important inequalities (including, for instance, the arithmetic–geometric mean inequality and Hölder's inequality).

Exponential growth is a special case of convexity. Exponential growth narrowly means "increasing at a rate proportional to the current value", while convex growth generally means "increasing at an increasing rate (but not necessarily proportionally to current value)".

Definition

Let  be a convex set in a real vector space and let f : X → R be a function.

be a convex set in a real vector space and let f : X → R be a function.

- f is called convex if:

- f is called strictly convex if:

- A function f is said to be (strictly) concave if −f is (strictly) convex.

Properties

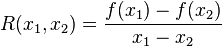

Suppose f is a function of one real variable defined on an interval, and let

(note that R(x1, x2) is the slope of the purple line in the above drawing; note also that the function R is symmetric in x1, x2). f is convex if and only if R(x1, x2) is monotonically non-decreasing in x1, for any fixed x2 (or vice versa). This characterization of convexity is quite useful to prove the following results.

A convex function f defined on some open interval C is continuous on C and Lipschitz continuous on any closed subinterval. f admits left and right derivatives, and these are monotonically non-decreasing. As a consequence, f is differentiable at all but at most countably many points. If C is closed, then f may fail to be continuous at the endpoints of C (an example is shown in the examples' section).

A function is midpoint convex on an interval C if

This condition is only slightly weaker than convexity. For example, a real valued Lebesgue measurable function that is midpoint convex will be convex by Sierpinski Theorem.[1] In particular, a continuous function that is midpoint convex will be convex.

A differentiable function of one variable is convex on an interval if and only if its derivative is monotonically non-decreasing on that interval. If a function is differentiable and convex then it is also continuously differentiable. For the basic case of a differentiable function from (a subset of) the real numbers to the real numbers, "convex" is equivalent to "increasing at an increasing rate".

A continuously differentiable function of one variable is convex on an interval if and only if the function lies above all of its tangents:[2]:69

for all x and y in the interval. In particular, if f′(c) = 0, then c is a global minimum of f(x).

A twice differentiable function of one variable is convex on an interval if and only if its second derivative is non-negative there; this gives a practical test for convexity. Visually, a twice differentiable convex function "curves up", without any bends the other way (inflection points). If its second derivative is positive at all points then the function is strictly convex, but the converse does not hold. For example, the second derivative of f(x) = x4 is f ′′(x) = 12x2, which is zero for x = 0, but x4 is strictly convex.

More generally, a continuous, twice differentiable function of several variables is convex on a convex set if and only if its Hessian matrix is positive semidefinite on the interior of the convex set.

Any local minimum of a convex function is also a global minimum. A strictly convex function will have at most one global minimum.

For a convex function f, the sublevel sets {x | f(x) < a} and {x | f(x) ≤ a} with a ∈ R are convex sets. However, a function whose sublevel sets are convex sets may fail to be a convex function. A function whose sublevel sets are convex is called a quasiconvex function.

Jensen's inequality applies to every convex function f. If X is a random variable taking values in the domain of f, then E(f(X)) ≥ f(E(X)). (Here E denotes the mathematical expectation.)

If a function f is convex, and f(0) ≤ 0, then f is superadditive on the positive reals.

Proof: Since f is convex, let y = 0, then:

From this we have:

Convex function calculus

- If f and g are convex functions, then so are

and

and

- If f and g are convex functions and g is non-decreasing, then

is convex. As an example, if f(x) is convex, then so is

is convex. As an example, if f(x) is convex, then so is  , because

, because  is convex and monotonically increasing.

is convex and monotonically increasing. - If f is concave and g is convex and non-increasing, then

is convex.

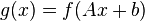

is convex. - Convexity is invariant under affine maps: that is, if f is convex with domain

, then so is

, then so is  , where

, where  with domain

with domain  .

. - If f(x, y) is convex in x then

is convex in x provided

is convex in x provided  for some x, even if C is not convex.

for some x, even if C is not convex. - If f(x) is convex, then its perspective

(whose domain is

(whose domain is  ) is convex.

) is convex. - The additive inverse of a convex function is a concave function.

- If

is a convex real valued function, then

is a convex real valued function, then  for a countable collection of real numbers

for a countable collection of real numbers

Strongly convex functions

The concept of strong convexity extends and parametrizes the notion of strict convexity. A strongly convex function is also strictly convex, but not vice versa.

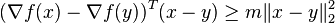

A differentiable function f is called strongly convex with parameter m > 0 if the following inequality holds for all points x, y in its domain:[3]

or, more generally,

where  is any norm. Some authors, such as [4] refer to functions satisfying this inequality as elliptic functions.

is any norm. Some authors, such as [4] refer to functions satisfying this inequality as elliptic functions.

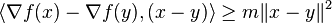

An equivalent condition is the following:[5]

It is not necessary for a function to be differentiable in order to be strongly convex. A third definition[5] for a strongly convex function, with parameter m, is that, for all x, y in the domain and ![t\in [0,1]](../I/m/d9a06fde4663cdd5b1ba693e9127232f.png) ,

,

Notice that this definition approaches the definition for strict convexity as m → 0, and is identical to the definition of a convex function when m = 0. Despite this, functions exist that are strictly convex but are not strongly convex for any m > 0 (see example below).

If the function f is twice continuously differentiable, then f is strongly convex with parameter m if and only if  for all x in the domain, where I is the identity and

for all x in the domain, where I is the identity and  is the Hessian matrix, and the inequality

is the Hessian matrix, and the inequality  means that

means that  is positive semi-definite. This is equivalent to requiring that the minimum eigenvalue of

is positive semi-definite. This is equivalent to requiring that the minimum eigenvalue of  be at least m for all x. If the domain is just the real line, then

be at least m for all x. If the domain is just the real line, then  is just the second derivative

is just the second derivative  , so the condition becomes

, so the condition becomes  . If m = 0, then this means the Hessian is positive semidefinite (or if the domain is the real line, it means that

. If m = 0, then this means the Hessian is positive semidefinite (or if the domain is the real line, it means that  ), which implies the function is convex, and perhaps strictly convex, but not strongly convex.

), which implies the function is convex, and perhaps strictly convex, but not strongly convex.

Assuming still that the function is twice continuously differentiable, one can show that the lower bound of  implies that it is strongly convex. Start by using Taylor's Theorem:

implies that it is strongly convex. Start by using Taylor's Theorem:

for some (unknown) ![z \in \{ t x + (1-t) y : t \in [0,1] \}](../I/m/c603edbcc6e64bcb6e8f3564d1f9af57.png) . Then

. Then

by the assumption about the eigenvalues, and hence we recover the second strong convexity equation above.

A function f is strongly convex with parameter m if and only if the function  is convex.

is convex.

The distinction between convex, strictly convex, and strongly convex can be subtle at first glimpse. If f is twice continuously differentiable and the domain is the real line, then we can characterize it as follows:

- f convex if and only if

for all x.

for all x. - f strictly convex if

for all x (note: this is sufficient, but not necessary).

for all x (note: this is sufficient, but not necessary). - f strongly convex if and only if

for all x.

for all x.

For example, consider a function f that is strictly convex, and suppose there is a sequence of points  such that

such that  . Even though

. Even though  the function is not strongly convex because

the function is not strongly convex because  will become arbitrarily small.

will become arbitrarily small.

A twice continuously differentiable function f on a compact domain  that satisfies

that satisfies  for all

for all  is strongly convex. The proof of this statement follows from the extreme value theorem, which states that a continuous function on a compact set has a maximum and minimum.

is strongly convex. The proof of this statement follows from the extreme value theorem, which states that a continuous function on a compact set has a maximum and minimum.

Strongly convex functions are in general easier to work with than convex or strictly convex functions, since they are a smaller class. Like strictly convex functions, strongly convex functions have unique minima on compact sets.

Uniformly convex functions

A uniformly convex function,[6][7] with modulus  , is a function f that, for all x, y in the domain and t ∈ [0, 1], satisfies

, is a function f that, for all x, y in the domain and t ∈ [0, 1], satisfies

where  is a function that is increasing and vanishes only at 0. This is a generalization of the concept of strongly convex function; by taking

is a function that is increasing and vanishes only at 0. This is a generalization of the concept of strongly convex function; by taking  we recover the definition of strong convexity.

we recover the definition of strong convexity.

Examples

- The function

has

has  at all points, so f is a convex function. It is also strongly convex (and hence strictly convex too), with strong convexity constant 2.

at all points, so f is a convex function. It is also strongly convex (and hence strictly convex too), with strong convexity constant 2. - The function

has

has  , so f is a convex function. It is strictly convex, even though the second derivative is not strictly positive at all points. It is not strongly convex.

, so f is a convex function. It is strictly convex, even though the second derivative is not strictly positive at all points. It is not strongly convex. - The absolute value function

is convex (as reflected in the triangle inequality), even though it does not have a derivative at the point x = 0. It is not strictly convex.

is convex (as reflected in the triangle inequality), even though it does not have a derivative at the point x = 0. It is not strictly convex. - The function

for 1 ≤ p is convex.

for 1 ≤ p is convex. - The exponential function

is convex. It is also strictly convex, since

is convex. It is also strictly convex, since  , but it is not strongly convex since the second derivative can be arbitrarily close to zero. More generally, the function

, but it is not strongly convex since the second derivative can be arbitrarily close to zero. More generally, the function  is logarithmically convex if fis a convex function. The term "superconvex" is sometimes used instead.[8]

is logarithmically convex if fis a convex function. The term "superconvex" is sometimes used instead.[8] - The function f with domain [0,1] defined by f(0) = f(1) = 1, f(x) = 0 for 0 < x < 1 is convex; it is continuous on the open interval (0, 1), but not continuous at 0 and 1.

- The function x3 has second derivative 6x; thus it is convex on the set where x ≥ 0 and concave on the set where x ≤ 0.

- The function

on the domain of positive-definite matrices is convex.[2]:74

on the domain of positive-definite matrices is convex.[2]:74 - Every real-valued linear transformation is convex but not strictly convex, since if fis linear, then

This statement also holds if we replace "convex" by "concave".

This statement also holds if we replace "convex" by "concave". - Every real-valued affine function, i.e., each function of the form

, is simultaneously convex and concave.

, is simultaneously convex and concave. - Every norm is a convex function, by the triangle inequality and positive homogeneity.

- Examples of functions that are monotonically increasing but not convex include

and g(x) = log(x).

and g(x) = log(x). - Examples of functions that are convex but not monotonically increasing include

and

and  .

. - The function f(x) = 1/x has

which is greater than 0 if x > 0, so f(x) is convex on the interval (0, +∞). It is concave on the interval (−∞, 0).

which is greater than 0 if x > 0, so f(x) is convex on the interval (0, +∞). It is concave on the interval (−∞, 0). - The function f(x) = x−2, with f(0) = +∞, is convex on the interval (0, +∞) and convex on the interval (-∞,0), but not convex on the interval (-∞, +∞), because of the singularity at x = 0.

See also

- Concave function

- Convex optimization

- Convex conjugate

- Geodesic convexity

- Kachurovskii's theorem, which relates convexity to monotonicity of the derivative

- Logarithmically convex function

- Pseudoconvex function

- Quasiconvex function

- Invex function

- Subderivative of a convex function

- Jensen's inequality

- Karamata's inequality

- Hermite–Hadamard inequality

- K-convex function

Notes

- ↑ Donoghue, William F. (1969). Distributions and Fourier Transforms. Academic Press. p. 12. ISBN 9780122206504. Retrieved August 29, 2012.

- 1 2 Boyd, Stephen P.; Vandenberghe, Lieven (2004). Convex Optimization (pdf). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83378-3. Retrieved October 15, 2011.

- ↑ Dimitri Bertsekas (2003). Convex Analysis and Optimization. Contributors: Angelia Nedic and Asuman E. Ozdaglar. Athena Scientific. p. 72. ISBN 9781886529458.

- ↑ Philippe G. Ciarlet (1989). Introduction to numerical linear algebra and optimisation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521339841.

- 1 2 Yurii Nesterov (2004). Introductory Lectures on Convex Optimization: A Basic Course. Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 63–64. ISBN 9781402075537.

- ↑ C. Zalinescu (2002). Convex Analysis in General Vector Spaces. World Scientific. ISBN 9812380671.

- ↑ H. Bauschke and P. L. Combettes (2011). Convex Analysis and Monotone Operator Theory in Hilbert Spaces. Springer. p. 144. ISBN 978-1-4419-9467-7.

- ↑ Kingman, J. F. C. (1961). "A Convexity Property of Positive Matrices". The Quarterly Journal of Mathematics 12: 283–284. doi:10.1093/qmath/12.1.283.

References

- Bertsekas, Dimitri (2003). Convex Analysis and Optimization. Athena Scientific.

- Borwein, Jonathan, and Lewis, Adrian. (2000). Convex Analysis and Nonlinear Optimization. Springer.

- Donoghue, William F. (1969). Distributions and Fourier Transforms. Academic Press.

- Hiriart-Urruty, Jean-Baptiste, and Lemaréchal, Claude. (2004). Fundamentals of Convex analysis. Berlin: Springer.

- Krasnosel'skii M.A., Rutickii Ya.B. (1961). Convex Functions and Orlicz Spaces. Groningen: P.Noordhoff Ltd.

- Lauritzen, Niels (2013). Undergraduate Convexity. World Scientific Publishing.

- Luenberger, David (1984). Linear and Nonlinear Programming. Addison-Wesley.

- Luenberger, David (1969). Optimization by Vector Space Methods. Wiley & Sons.

- Rockafellar, R. T. (1970). Convex analysis. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Thomson, Brian (1994). Symmetric Properties of Real Functions. CRC Press.

- Zălinescu, C. (2002). Convex analysis in general vector spaces. River Edge, NJ: World Scientific Publishing Co., Inc. pp. xx+367. ISBN 981-238-067-1. MR 1921556.

External links

- Stephen Boyd and Lieven Vandenberghe, Convex Optimization (PDF)

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Convex function (of a real variable)", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Convex function (of a complex variable)", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

|

![\forall x_1, x_2 \in X, \forall t \in [0, 1]: \qquad f(tx_1+(1-t)x_2)\leq t f(x_1)+(1-t)f(x_2).](../I/m/78dc74f02d80babd3d6276a7ab18a809.png)

![f(tx) = f(tx+(1-t)\cdot 0) \le t f(x)+(1-t)f(0) \le t f(x), \quad \forall t \in[0,1].](../I/m/930ad6c1b088d1af333221211a92bc88.png)