Continuum hypothesis

In mathematics, the continuum hypothesis (abbreviated CH) is a hypothesis about the possible sizes of infinite sets. It states:

- There is no set whose cardinality is strictly between that of the integers and the real numbers.

The continuum hypothesis was advanced by Georg Cantor in 1878, and establishing its truth or falsehood is the first of Hilbert's 23 problems presented in 1900. Τhe answer to this problem is independent of ZFC set theory (that is, Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory with the axiom of choice included), so that either the continuum hypothesis or its negation can be added as an axiom to ZFC set theory, with the resulting theory being consistent if and only if ZFC is consistent. This independence was proved in 1963 by Paul Cohen, complementing earlier work by Kurt Gödel in 1940.

The name of the hypothesis comes from the term the continuum for the real numbers.

Cardinality of infinite sets

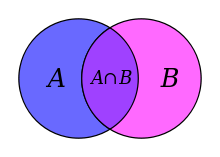

Two sets are said to have the same cardinality or cardinal number if there exists a bijection (a one-to-one correspondence) between them. Intuitively, for two sets S and T to have the same cardinality means that it is possible to "pair off" elements of S with elements of T in such a fashion that every element of S is paired off with exactly one element of T and vice versa. Hence, the set {banana, apple, pear} has the same cardinality as {yellow, red, green}.

With infinite sets such as the set of integers or rational numbers, this becomes more complicated to demonstrate. The rational numbers seemingly form a counterexample to the continuum hypothesis: the integers form a proper subset of the rationals, which themselves form a proper subset of the reals, so intuitively, there are more rational numbers than integers, and more real numbers than rational numbers. However, this intuitive analysis does not take account of the fact that all three sets are infinite. It turns out the rational numbers can actually be placed in one-to-one correspondence with the integers, and therefore the set of rational numbers is the same size (cardinality) as the set of integers: they are both countable sets.

Cantor gave two proofs that the cardinality of the set of integers is strictly smaller than that of the set of real numbers (see Cantor's first uncountability proof and Cantor's diagonal argument). His proofs, however, give no indication of the extent to which the cardinality of the integers is less than that of the real numbers. Cantor proposed the continuum hypothesis as a possible solution to this question.

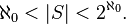

The hypothesis states that the set of real numbers has minimal possible cardinality which is greater than the cardinality of the set of integers. Equivalently, as the cardinality of the integers is  ("aleph-naught") and the cardinality of the real numbers is

("aleph-naught") and the cardinality of the real numbers is  (i.e. it equals the cardinality of the power set of the integers), the continuum hypothesis says that there is no set

(i.e. it equals the cardinality of the power set of the integers), the continuum hypothesis says that there is no set  for which

for which

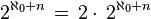

Assuming the axiom of choice,  , and the continuum hypothesis is in turn equivalent to the equality

, and the continuum hypothesis is in turn equivalent to the equality

A consequence of the continuum hypothesis is that every infinite subset of the real numbers either has the same cardinality as the integers or the same cardinality as the entire set of the reals.

There is also a generalization of the continuum hypothesis called the generalized continuum hypothesis (GCH) which says that for all ordinals

That is, GCH asserts that the cardinality of the power set of any infinite set is the smallest cardinality greater than that of the set.

Independence from ZFC

Cantor believed the continuum hypothesis to be true and tried for many years to prove it, in vain (Dauben 1990). It became the first on David Hilbert's list of important open questions that was presented at the International Congress of Mathematicians in the year 1900 in Paris. Axiomatic set theory was at that point not yet formulated.

Kurt Gödel showed in 1940 that the continuum hypothesis (CH for short) cannot be disproved from the standard Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory (ZF), even if the axiom of choice is adopted (ZFC) (Gödel (1940)). Paul Cohen showed in 1963 that CH cannot be proven from those same axioms either (Cohen (1963) & Cohen (1964)). Hence, CH is independent of ZFC. Both of these results assume that the Zermelo–Fraenkel axioms are consistent; this assumption is widely believed to be true. Cohen was awarded the Fields Medal in 1966 for his proof.

The continuum hypothesis is closely related to many statements in analysis, point set topology and measure theory. As a result of its independence, many substantial conjectures in those fields have subsequently been shown to be independent as well.

So far, CH appears to be independent of all known large cardinal axioms in the context of ZFC. (Feferman (1999))

The independence from ZFC means that proving or disproving the CH within ZFC is impossible. However, Gödel and Cohen's negative results are not universally accepted as disposing of the hypothesis. Hilbert's problem remains an active topic of research; see Woodin (2001) and Koellner (2011a) for an overview of the current research status.

The continuum hypothesis was not the first statement shown to be independent of ZFC. An immediate consequence of Gödel's incompleteness theorem, which was published in 1931, is that there is a formal statement (one for each appropriate Gödel numbering scheme) expressing the consistency of ZFC that is independent of ZFC, assuming that ZFC is consistent. The continuum hypothesis and the axiom of choice were among the first mathematical statements shown to be independent of ZF set theory. These proofs of independence were not completed until Paul Cohen developed forcing in the 1960s. They all rely on the assumption that ZF is consistent. These proofs are called proofs of relative consistency (see Forcing (mathematics)).

A result of Solovay, proved shortly after Cohen's result on the independence of the continuum hypothesis, shows that in any model of ZFC, if  is a cardinal of uncountable cofinality, then there is a forcing extension in which

is a cardinal of uncountable cofinality, then there is a forcing extension in which  . However, it is not consistent to assume

. However, it is not consistent to assume  is

is  or

or  or any cardinal with cofinality

or any cardinal with cofinality  .

.

Arguments for and against CH

Gödel believed that CH is false and that his proof that CH is consistent with ZFC only shows that the Zermelo–Fraenkel axioms do not adequately characterize the universe of sets. Gödel was a platonist and therefore had no problems with asserting the truth and falsehood of statements independent of their provability. Cohen, though a formalist (Goodman 1979), also tended towards rejecting CH.

Historically, mathematicians who favored a "rich" and "large" universe of sets were against CH, while those favoring a "neat" and "controllable" universe favored CH. Parallel arguments were made for and against the axiom of constructibility, which implies CH. More recently, Matthew Foreman has pointed out that ontological maximalism can actually be used to argue in favor of CH, because among models that have the same reals, models with "more" sets of reals have a better chance of satisfying CH (Maddy 1988, p. 500).

Another viewpoint is that the conception of set is not specific enough to determine whether CH is true or false. This viewpoint was advanced as early as 1923 by Skolem, even before Gödel's first incompleteness theorem. Skolem argued on the basis of what is now known as Skolem's paradox, and it was later supported by the independence of CH from the axioms of ZFC, since these axioms are enough to establish the elementary properties of sets and cardinalities. In order to argue against this viewpoint, it would be sufficient to demonstrate new axioms that are supported by intuition and resolve CH in one direction or another. Although the axiom of constructibility does resolve CH, it is not generally considered to be intuitively true any more than CH is generally considered to be false (Kunen 1980, p. 171).

At least two other axioms have been proposed that have implications for the continuum hypothesis, although these axioms have not currently found wide acceptance in the mathematical community. In 1986, Chris Freiling presented an argument against CH by showing that the negation of CH is equivalent to Freiling's axiom of symmetry, a statement about probabilities. Freiling believes this axiom is "intuitively true" but others have disagreed. A difficult argument against CH developed by W. Hugh Woodin has attracted considerable attention since the year 2000 (Woodin 2001a, 2001b). Foreman (2003) does not reject Woodin's argument outright but urges caution.

Solomon Feferman (2011) has made a complex philosophical argument that CH is not a definite mathematical problem. He proposes a theory of "definiteness" using a semi-intuitionistic subsystem of ZF that accepts classical logic for bounded quantifiers but uses intuitionistic logic for unbounded ones, and suggests that a proposition  is mathematically "definite" if the semi-intuitionistic theory can prove

is mathematically "definite" if the semi-intuitionistic theory can prove  . He conjectures that CH is not definite according to this notion, and proposes that CH should therefore be considered not to have a truth value. Peter Koellner (2011b) wrote a critical commentary on Feferman's article.

. He conjectures that CH is not definite according to this notion, and proposes that CH should therefore be considered not to have a truth value. Peter Koellner (2011b) wrote a critical commentary on Feferman's article.

Joel David Hamkins proposes a multiverse approach to set theory and argues that "the continuum hypothesis is settled on the multiverse view by our extensive knowledge about how it behaves in the multiverse, and as a result it can no longer be settled in the manner formerly hoped for." (Hamkins 2012). In a related vein, Saharon Shelah wrote that he does "not agree with the pure Platonic view that the interesting problems in set theory can be decided, that we just have to discover the additional axiom. My mental picture is that we have many possible set theories, all conforming to ZFC." (Shelah 2003).

The generalized continuum hypothesis

The generalized continuum hypothesis (GCH) states that if an infinite set's cardinality lies between that of an infinite set S and that of the power set of S, then it either has the same cardinality as the set S or the same cardinality as the power set of S. That is, for any infinite cardinal  there is no cardinal

there is no cardinal  such that

such that  GCH is equivalent to:

GCH is equivalent to:

for every ordinal

for every ordinal  (occasionally called Cantor's aleph hypothesis)

(occasionally called Cantor's aleph hypothesis)

The beth numbers provide an alternate notation for this condition:  for every ordinal

for every ordinal

This is a generalization of the continuum hypothesis since the continuum has the same cardinality as the power set of the integers. It was first suggested by Jourdain (1905).

Like CH, GCH is also independent of ZFC, but Sierpiński proved that ZF + GCH implies the axiom of choice (AC) (and therefore the negation of the axiom of determinacy, AD), so choice and GCH are not independent in ZF; there are no models of ZF in which GCH holds and AC fails. To prove this, Sierpiński showed GCH implies that every cardinality n is smaller than some Aleph number, and thus can be ordered. This is done by showing that n is smaller than  which is smaller than its own Hartogs number — this uses the equality

which is smaller than its own Hartogs number — this uses the equality  ; for the full proof, see Gillman (2002).

; for the full proof, see Gillman (2002).

Kurt Gödel showed that GCH is a consequence of ZF + V=L (the axiom that every set is constructible relative to the ordinals), and is therefore consistent with ZFC. As GCH implies CH, Cohen's model in which CH fails is a model in which GCH fails, and thus GCH is not provable from ZFC. W. B. Easton used the method of forcing developed by Cohen to prove Easton's theorem, which shows it is consistent with ZFC for arbitrarily large cardinals  to fail to satisfy

to fail to satisfy  Much later, Foreman and Woodin proved that (assuming the consistency of very large cardinals) it is consistent that

Much later, Foreman and Woodin proved that (assuming the consistency of very large cardinals) it is consistent that  holds for every infinite cardinal

holds for every infinite cardinal  Later Woodin extended this by showing the consistency of

Later Woodin extended this by showing the consistency of  for every

for every  . A recent result of Carmi Merimovich shows that, for each n≥1, it is consistent with ZFC that for each κ, 2κ is the nth successor of κ. On the other hand, László Patai (1930) proved, that if γ is an ordinal and for each infinite cardinal κ, 2κ is the γth successor of κ, then γ is finite.

. A recent result of Carmi Merimovich shows that, for each n≥1, it is consistent with ZFC that for each κ, 2κ is the nth successor of κ. On the other hand, László Patai (1930) proved, that if γ is an ordinal and for each infinite cardinal κ, 2κ is the γth successor of κ, then γ is finite.

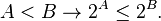

For any infinite sets A and B, if there is an injection from A to B then there is an injection from subsets of A to subsets of B. Thus for any infinite cardinals A and B,

If A and B are finite, the stronger inequality

holds. GCH implies that this strict, stronger inequality holds for infinite cardinals as well as finite cardinals.

Implications of GCH for cardinal exponentiation

Although the generalized continuum hypothesis refers directly only to cardinal exponentiation with 2 as the base, one can deduce from it the values of cardinal exponentiation in all cases. It implies that  is (see: Hayden & Kennison (1968), page 147, exercise 76):

is (see: Hayden & Kennison (1968), page 147, exercise 76):

when α ≤ β+1;

when α ≤ β+1; when β+1 < α and

when β+1 < α and  where cf is the cofinality operation; and

where cf is the cofinality operation; and when β+1 < α and

when β+1 < α and  .

.

See also

References

- Cohen, Paul Joseph (2008) [1966]. Set theory and the continuum hypothesis. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-46921-8.

- Cohen, Paul J. (December 15, 1963). "The Independence of the Continuum Hypothesis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 50 (6): 1143–1148. doi:10.1073/pnas.50.6.1143. JSTOR 71858. PMC 221287. PMID 16578557.

- Cohen, Paul J. (January 15, 1964). "The Independence of the Continuum Hypothesis, II". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 51 (1): 105–110. doi:10.1073/pnas.51.1.105. JSTOR 72252. PMC 300611. PMID 16591132.

- Dales, H. G.; Woodin, W. H. (1987). An Introduction to Independence for Analysts. Cambridge.

- Dauben, Joseph Warren (1990). Georg Cantor: His Mathematics and Philosophy of the Infinite. Princeton University Press. pp. 134–137. ISBN 9780691024479.

- Enderton, Herbert (1977). Elements of Set Theory. Academic Press.

- Feferman, Solomon (February 1999). "Does mathematics need new axioms?". American Mathematical Monthly 106 (2): 99–111. doi:10.2307/2589047.

- Feferman, Solomon (2011). "Is the Continuum Hypothesis a definite mathematical problem?" (PDF). Exploring the Frontiers of Independence (Harvard lecture series). External link in

|work=(help) - Foreman, Matt (2003). "Has the Continuum Hypothesis been Settled?" (PDF). Retrieved February 25, 2006.

- Freiling, Chris (1986). "Axioms of Symmetry: Throwing Darts at the Real Number Line". Journal of Symbolic Logic (Association for Symbolic Logic) 51 (1): 190–200. doi:10.2307/2273955. JSTOR 2273955.

- Gödel, K. (1940). The Consistency of the Continuum-Hypothesis. Princeton University Press.

- Gillman, Leonard (2002). "Two Classical Surprises Concerning the Axiom of Choice and the Continuum Hypothesis" (PDF). American Mathematical Monthly 109. doi:10.2307/2695444.

- Gödel, K.: What is Cantor's Continuum Problem?, reprinted in Benacerraf and Putnam's collection Philosophy of Mathematics, 2nd ed., Cambridge University Press, 1983. An outline of Gödel's arguments against CH.

- Goodman, Nicolas D. (1979). "Mathematics as an objective science". The American Mathematical Monthly 86 (7): 540–551. doi:10.2307/2320581. MR 542765.

This view is often called formalism. Positions more or less like this may be found in Haskell Curry [5], Abraham Robinson [17], and Paul Cohen [4].

- Joel David Hamkins. The set-theoretic multiverse. Rev. Symb. Log. 5 (2012), no. 3, 416–449.

- Seymour Hayden and John F. Kennison: Zermelo–Fraenkel Set Theory (1968), Charles E. Merrill Publishing Company, Columbus, Ohio.

- Jourdain, Philip E. B. (1905). "On transfinite cardinal numbers of the exponential form". Philosophical Magazine, Series 6 9: 42–56. doi:10.1080/14786440509463254.

- Koellner, Peter (2011a). "The Continuum Hypothesis" (PDF). Exploring the Frontiers of Independence (Harvard lecture series).

- Koellner, Peter (2011b). "Feferman On the Indefiniteness of CH" (PDF).

- Kunen, Kenneth (1980). Set Theory: An Introduction to Independence Proofs. Amsterdam: North-Holland. ISBN 978-0-444-85401-8.

- Maddy, Penelope (June 1988). "Believing the Axioms, I". Journal of Symbolic Logic (Association for Symbolic Logic) 53 (2): 481–511. doi:10.2307/2274520. JSTOR 2274520.

- Martin, D. (1976). "Hilbert's first problem: the continuum hypothesis," in Mathematical Developments Arising from Hilbert's Problems, Proceedings of Symposia in Pure Mathematics XXVIII, F. Browder, editor. American Mathematical Society, 1976, pp. 81–92. ISBN 0-8218-1428-1

- McGough, Nancy. "The Continuum Hypothesis".

- Merimovich, Carmi (2007). "A power function with a fixed finite gap everywhere". Journal of Symbolic Logic 72 (2): 361–417. doi:10.2178/jsl/1185803615.

- Moore, Gregory H. (2011). "Early history of the generalized continuum hypothesis: 1878–1938". Bull. Symbolic Logic 17 (4): 489–532. doi:10.2178/bsl/1318855631. MR 2896574.

- Shelah, Saharon (2003). "Logical dreams". Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. (N.S.) 40 (2): 203–228. doi:10.1090/s0273-0979-03-00981-9.

- Woodin, W. Hugh (2001a). "The Continuum Hypothesis, Part I" (PDF). Notices of the AMS 48 (6): 567–576.

- Woodin, W. Hugh (2001b). "The Continuum Hypothesis, Part II" (PDF). Notices of the AMS 48 (7): 681–690.

- German literature

- Cantor, Georg (1878). "Ein Beitrag zur Mannigfaltigkeitslehre". Journal für die Reine und Angewandte Mathematik 84: 242–258. doi:10.1515/crll.1878.84.242.

- Patai, L. (1930). "Untersuchungen über die א-reihe". Mathematische und naturwissenschaftliche Berichte aus Ungarn 37: 127–142.

External links

- Szudzik, Matthew and Weisstein, Eric W., "Continuum Hypothesis", MathWorld.

This article incorporates material from Generalized continuum hypothesis on PlanetMath, which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||