Continuous noninvasive arterial pressure

Continuous noninvasive arterial pressure (CNAP) is the method of measuring arterial blood pressure in real-time without any interruptions (continuously) and without cannulating the human body (noninvasive).

This article explains the benefit, the evolution and the clinical significance of continuous noninvasive blood pressure monitoring with special attention to recent technological progress in this area. A brief review of blood pressure measurement methods in order to understand the historical gap between bulky continuous “pulse writers” (sphygmographs) and easy to use and accurate noninvasive upper arm blood pressure instruments shall complete this survey.

Benefit of CNAP technology

Continuous noninvasive arterial blood pressure measurement (CNAP) combines the advantages of the following two clinical “gold standards”: it measures blood pressure (BP) continuously in real-time like the invasive arterial catheter system (IBP) and it is non-invasive like the standard upper arm sphygmomanometer (NBP). Latest developments in this field show promising results in terms of accuracy, ease of use and clinical acceptance.

Clinical requirements

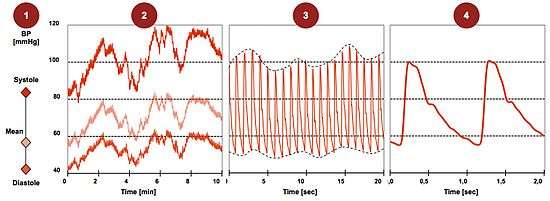

For the use in clinical environment a CNAP system must provide the following blood pressure information:

- Absolute blood pressure obtained from a proximal artery (e.g. arteria brachialis)

- Blood pressure changes in order to detect hemodynamic instabilities

- Physiological rhythms that deliver insight into the hemodynamic control function and/or fluid management

- Blood pressure pulse waves for quality control – further pulse wave analysis provides additional cardiovascular parameters such as stroke volume, cardiac output and arterial stiffness.

A high demand for easily applicable and accurate CNAP-systems is proven. This is why researchers, practitioners and the medical device industry focus on such devices. Like in other fields of innovation, the use of small but powerful microcomputers and digital signal processors facilitates the development of efficient blood pressure measurement instruments. These processors enable complex and computationally intensive mathematical functions in small inexpensive devices, which are necessary for this purpose.

Medical need and outcome

Recent literature,[1] a nationally representative survey among 200 German and Austrian physicians[2] and additional expert interviews provide strong evidence that in only 15% to 18% of inpatient surgeries blood pressure is measured continuously with invasive catheters (IBP). In all other inpatient and outpatient surgeries intermittent, noninvasive blood pressure (NBP) monitoring is the standard of care. Due to the discontinuous character of NBP, dangerous hypotensive episodes might be missed: In women undergoing Caesarean section, CNAP detected hypotensive phases in 39% of the cases, whereas only 9% were detected by the standard NBP.[3] Dangerous fetal acidosis did not occur when systolic blood pressure measured with CNAP was above 100mmHg.[3] Another study showed more than 22% of missed hypotensive episodes leading to delayed or no treatment.[4]

Hemodynamic optimization

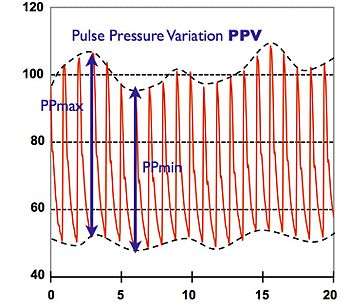

A further advantage of CNAP is hemodynamic optimization using continuous blood pressure and its parameters derived from physiological rhythms and pulse wave analysis. The concept has quickly found wide acceptance in anesthesia and critical care: The evaluation of Pulse Pressure Variation (PPV) allows for goal-directed fluid management in sedated and ventilated patients.[5][6]

Further, the mathematical analysis of CNAP pulse waves enables the noninvasive estimation of stroke volume and cardiac output.[7] A meta-analysis of 29 clinical trials evidences that goal-directed therapy using these hemodynamic parameters leads to lower rates of morbidity and mortality in moderate and high-risk surgical procedures.[8]

Current noninvasive blood pressure technologies

Detecting pressure changes inside an artery from the outside is difficult, whereas volume and flow changes of the artery can well be determined by using e.g. light, echography, impedance, etc. But unfortunately these volume changes are not linearly correlated with the arterial pressure– especially when measured in the periphery, where the access to the arteries is easy. Thus, noninvasive devices have to find a way to transform the peripheral volume signal to arterial pressure.

Vascular unloading technique

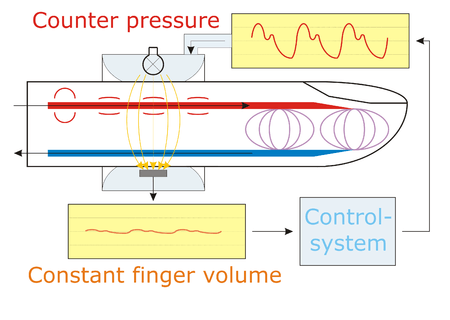

Pulse oximeters can measure finger blood volume changes using light. These volume changes must be transformed into pressure, because of the non-linearity of the elastic components of the arterial wall as well as the non-elastic parts of the smooth muscles of the finger artery.

The method is to unload the arterial wall in order to linearize this phenomenon with a counter pressure as high as the pressure inside the artery. Blood volume is kept constant by applying this corresponding pressure from the outside. The continuously changing outside pressure that is needed to keep the arterial blood volume constant directly corresponds to the arterial pressure. This is the basic principle of the so-called “Vascular Unloading Technique”.

For the realization, a cuff is placed over the finger. Inside the cuff, the blood volume in the finger arteries is measured using a light source and a light detector. The resulting light signal is kept constant by controlling the alterable cuff pressure. During systole, when blood volume increases in the finger, the control system increases cuff pressure, too, until the excess blood volume is squeezed out. On the other hand, during diastole, the blood volume in the finger is decreased; as a result, cuff pressure is lowered and again the overall blood volume remains constant. As blood volume and, thus, the light signal is held constant over time, intra-arterial pressure is equal to the cuff pressure. This pressure can easily be measured with a manometer.

As the volume of the finger artery is clamped on a constant diameter, the method is also known as “Volume Clamped Method”.

The Czech physiologist Jan Peňáz introduced this type of measurement of continuous noninvasive arterial blood pressure in 1973 by means of an electro-pneumatic control loop.[9] Two research groups have improved this method:

- An Austrian group has developed a complete digital approach of the method in the last 8 years.[10] As a result, this technology can be found in the Task Force Monitor and CNAP Monitor 500 (CNSystems) as well as in the CNAP Smart Pod (Dräger Medical) and in the LiDCOrapid (LiDCO Ltd.)[11]

- A group from the Netherlands has developed the Finapres system in the 1980s.[12] Successors of the Finapres systems on the medical market are the Finometer and the Portapres (FMS) as well as the Nexfin.

- A Russian group has developed the Spiroarteriocardiorhythmograph (SACR) system in the 2004.[13] The SACR provides continuous noninvasive measurement of arterial pressure, detection of inhaled and exhaled airflows with an ultrasonic spirometer, electrocardiogram detection, and joint analysis of these dynamic processes.[14]

Tonometry

The non-linear effect of the vascular wall decreases in bigger arteries. It is well known that good access to a “big” artery is at the wrist by palpating. Different mechanisms have been developed for the automatic noninvasive palpation on the arteria radialis.[15] In order to obtain a stable blood pressure signal, the tonometric sensor must be protected against movement and other mechanical artifacts.

Pulse transit time

When the heart ejects stroke volume to the arteries, it takes a certain transit time until the blood pressure wave arrives in the periphery. This pulse transit time (PTT) indirectly depends on blood pressure – the higher the pressure, the faster PTT. This circumstance can be used for the noninvasive detection of blood pressure changes.[16][17] For absolute values, this method needs calibration.

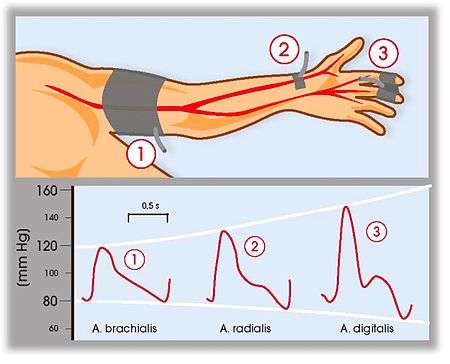

Calibration and correction to proximal arteries

All methods measure peripheral arterial pressure, which is inherently different from the blood pressure detected from proximal arteries. Even the comparison between the two clinical “gold standards” invasive continuous blood pressure at the arteria radialis and noninvasive, but intermittent, upper arm cuff shows huge differences.[18]

Physicians are trained to derive treatment decisions from proximal arteries – e.g. noninvasively from the arteria brachialis. Calibration to the noninvasive “gold standard” NBP is performed in most of the devices that are currently marketed, although the calibration methods differ:

- The CNAP technology from the Austrian group obtains a standard NBP measurement at the beginning of the measurement. An individual transfer function from finger to upper arm is then calculated and applied to the CNAP-signal.[10]

- All Finapres successor devices apply a global transfer function for finger to brachial values and the Finometer Pro as well as the FInapres NOVA use an upper arm cuff as well. Besides a Height Correction Unit (HCU) is used, the upperarm cuff is only used ones in the beginning of every test, this because the Finapres technology uses a so-called Physiocalibration. The CNAP technology does not have this Physiocalibration for which regular inflating the upperarm cuff must be performed.This transfer function compensates damping up to 2.5 Hz with an amplification of the signal of 1.2.[19] Hence, the devices generally increase the beat-to-beat values to 120% of the finger values. An exception is the Finometer – beside this global function it also considers the offset between finger and upper arm with a cuff.[20]

Changes in arterial tone

The pitfall of all noninvasive technologies is change in vascular tone. Small arteries beginning from arteria radialis downwards to the periphery have smooth muscles in order to open (vasodilation) and close (vasoconstriction). This human mechanism is activated by sympathetic tone and is further influenced by vasoactive drugs. Especially in critical care, vasoactive drugs are needed to control and maintain sedation and blood pressure. Mathematically advanced correction methods have to be developed for these noninvasive technologies in order to fulfill accuracy and clinical acceptance:

VERIFI

The VERIFI-algorithm corrects vasomotor tone by means of a fast pulse wave analysis. It establishes correct mean arterial blood pressure in the finger cuff by checking typical characteristics of the pulse wave. VERIFI-correction is performed after every heart beat, as vasomotor changes can occur immediately. This allows for a true continuous CNAP-signal without interruption during hemodynamic instable situations. VERIFI is implemented in the Task Force Monitor, CNAP Monitor 500, CNAP Smart Pod and in the LiDCOrapid.[10]

PhysioCal

PhysioCal is used in Finapres and its successor devices. The so-called PhysioCal algorithm eliminates the changes in tone of smooth muscles in the arterial wall, the hematocrit and other finger volume changes during measurement periods of constant pressure. Physiocal is achieved by opening the Vascular Unloading feedback loop. A new pressure ramp search is then performed before the measurement starts again. This algorithm needs to interrupt the blood pressure tracings for recalibration purposes, which results in short data loss during that time.[21]

Repeated calibration

For other methods like PTT, a closed-mashed re-calibration to NBP can overcome vasomotor changes.

Accuracy

The overall accuracy of CNAP devices has been demonstrated in comparison with the current gold standard invasive blood pressure (IBP) in numerous studies during the last few years. As examples, investigators came to the following conclusions:

- "... These findings indicate that CNAP provides real-time estimates of arterial pressure comparable with those generated by an invasive intra- arterial catheter system during general anesthesia."[22]

- „... for mean arterial pressure measurement more than 90% of the CNAP measurements present a bias of less than 10% with the reference.“[23]

- “..We conclude CNAP is a reliable, noninvasive, continuous blood pressure monitor ... CNAP can be used as an alternative to IBP.”[24]

- “Arterial blood pressure can be measured non- invasively and continuously using physiologic pressure reconstruction. Changes in pressure can be followed and values are comparable to invasive monitoring.”[25]

See also

References

- ↑ Maguire, S., Rinehart, J., Vakharia, S., & Cannesson, M. (2011). Technical communication: respiratory variation in pulse pressure and plethysmographic waveforms: intraoperative applicability in a North American academic center. Anesthesia and analgesia, 112(1), 94–6.

- ↑ von Skerst B: Market survey, N=198 physicians in Germany and Austria, Dec.2007 - Mar 2008, InnoTech Consult GmbH, Germany

- 1 2 Ilies, C., Kiskalt, H., Siedenhans, D., Meybohm, P., Steinfath, M., Bein, B., & Hanss, R. (2012). Detection of hypotension during Caesarean section with continuous non-invasive arterial pressure device or intermittent oscillometric arterial pressure measurement. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 3–9.

- ↑ Dueck R, Jameson LC. Reliability of hypotension detection with noninvasive radial artery beat-to-beat versus upper arm cuff BP monitoring. Anesth Analg 2006, 102 Suppl:S10

- ↑ Michard, F., Chemla, D., Richard, C., Wysocki, M., Pinsky, M. R., Lecarpentier, Y., & Teboul, J. L. (1999). Clinical use of respiratory changes in arterial pulse pressure to monitor the hemodynamic effects of PEEP. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine, 159(3), 935–9.

- ↑ Michard, F., Warltier, D. C., & Ph, D. (2005). Changes in arterial pressure during mechanical ventilation. Anesthesiology, 103(2), 419–28; quiz 449–5.

- ↑ Wesseling, K. H., Jansen, J. R., Settels, J. J., & Schreuder, J. J. (1993). Computation of aortic flow from pressure in humans using a nonlinear , three-element model Computation of aortic flow from pressure in humans using a nonlinear , three-element. Journal of Applied Physiology (1993), 74(5), 2566–2573.

- ↑ Hamilton, M. a, Cecconi, M., & Rhodes, A. (2010). A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on the Use of Preemptive Hemodynamic Intervention to Improve Postoperative Outcomes in Moderate and High-Risk Surgical Patients. Anesthesia and analgesia, 112(6), 1392–402.

- ↑ Peňáz J: Photoelectric Measurement of blood pressure, volume and flow in the finger. Digest of the 10th international conference on medical and biological engineering – Dresden (1973).

- 1 2 3 Fortin, J., Marte, W., Grüllenberger, R., Hacker, A., Habenbacher, W., Heller, A., Wagner, C., et al. (2006). Continuous non-invasive blood pressure monitoring using concentrically interlocking control loops. Computers in biology and medicine, 36(9), 941–57.

- ↑ http://www.cnsystems.at

- ↑ Imholz, B. P., Wieling, W., van Montfrans, G. A., Wesseling, K. H. (1998). Fifteen years experience with finger arterial pressure monitoring: assessment of the technology. Cardiovascular research, 38(3), 605–16.

- ↑ http://cakp.ru/

- ↑ Pivovarov V. V. A Spiroarteriocardiorhythmograph.\\ Biomedical Engineering January 2006, Volume 40, Issue 1, pp 45-47.

- ↑ http://www.tensysmedical.com, http://www.atcor.com. http://www.hdii.com

- ↑ http://www.soterawireless.com

- ↑ Solà, Josep (2011). Continuous non-invasive blood pressure estimation (PDF). Zurich: ETHZ PhD dissertation.

- ↑ Wax, D. B., Lin, H.-M., & Leibowitz, A. B. (2011). Invasive and concomitant noninvasive intraoperative blood pressure monitoring: observed differences in measurements and associated therapeutic interventions. Anesthesiology, 115(5), 973–8

- ↑ Bos, W. J. W., van Goudoever, J., van Montfrans, G. A., Van Den Meiracker, a H., & Wesseling, K. H. (1996). Reconstruction of brachial artery pressure from noninvasive finger pressure measurements. Circulation, 94(8), 1870–5.

- ↑ http://www.finapres.com

- ↑ Wesseling KH., de Wit B., van der Hoeven G. M. A., van Goudoever J., Settels J. J.: Physiocal, calibrating finger vascular physiology for Finapres. Homeostasis. 36(2-3):76-82, 1995.

- ↑ Jeleazcov, C., Krajinovic, L., Münster, T., Birkholz, T., Fried, R., Schüttler, J., & Fechner, J. (2010). Precision and accuracy of a new device (CNAPTM) for continuous non-invasive arterial pressure monitoring: assessment during general anaesthesia. British journal of anaesthesia, 105(3), 264–72.

- ↑ Biais, M., Vidil, L., Roullet, S., Masson, F., Quinart, A., Revel, P., & Sztark, F. (2010). Continuous non-invasive arterial pressure measurement: evaluation of CNAP device during vascular surgery. Annales françaises d’anesthèsie et de rèanimation, 29(7-8), 530–5.

- ↑ Jagadeesh, a M., Singh, N. G., & Mahankali, S. (2012). A comparison of a continuous noninvasive arterial pressure (CNAPTM) monitor with an invasive arterial blood pressure monitor in the cardiac surgical ICU. Annals of cardiac anaesthesia, 15(3), 180–4.

- ↑ Jerson R. Martina, Hollmann, M. W., Ph, D., & Lahpor, J. R. (2012). Noninvasive Continuous Arterial Blood Pressure Monitoring with Nexfin ®. Anesthesiology, 116, :1092–103.