Constellation

| |||

| |||

In modern astronomy, a constellation is a specific area of the celestial sphere as defined by the International Astronomical Union (IAU). These areas mostly had their origins in Western-traditional asterisms from which the constellations take their names. There are 88 officially recognized constellations, covering the entire sky.[1]

Thus, any given point in a celestial coordinate system can unambiguously be assigned to a constellation. It is usual in astronomy to give the constellation in which a given object is found along with its coordinates in order to convey a rough idea in which part of the sky it is located.

Terminology

The origin of the word constellation seems to come from the Late Latin term "cōnstellātiō," which can be translated as "set of stars", but came into use in English during the 14th century. A more modern astronomical sense of the term is as a recognisable pattern of stars whose appearance is identified with mythological characters or creatures, or associated earthbound animals or objects.

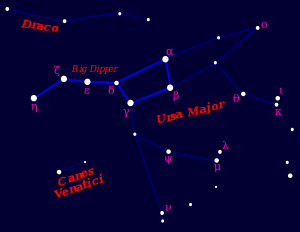

Colloquial usage does not draw a sharp distinction between "constellation" in the sense of an asterism (pattern of stars) and "constellation" in the sense of an area surrounding an asterism. The modern system of constellations used in astronomy employs the latter concept. For example, the northern asterism known as the Big Dipper comprises the seven brightest stars in the IAU constellation (area) Ursa Major while the southern False Cross includes portions of the constellations Carina and Vela.

The term circumpolar constellation is used for any constellation that, from a particular latitude on Earth, never sets below the horizon. From the North Pole or South Pole, all constellations north or south of the celestial equator are circumpolar constellations. In the equatorial or temperate latitudes, the informal term equatorial constellation has sometimes been used for constellations that lie to the opposite the circumpolar constellations.[2] Depending on the definition, equatorial constellations can include those that lie entirely between declinations 45° north and 45° south,[3] or those that pass overhead between the tropics of Cancer and Capricorn between declinations of 23½° north and 23½° south. They generally include all constellations that intersect the celestial equator or part of the zodiac.

Usually the only thing the stars in a constellation have in common is that they appear near each other in the sky when viewed from the Earth, but in galactic space, most constellation stars lie at a variety of distances. Since stars also travel on their own orbits through the Milky Way, the star patterns of the constellations change slowly over time. After tens to hundreds of thousands of years, their familiar outlines will become unrecognisable.[4]

History

The earliest direct evidence for the constellations comes from inscribed stones and clay writing tablets dug up in Mesopotamia (within modern Iraq) dating back to 3000 BC.[5] It seems that the bulk of the Mesopotamian constellations were created within a relatively short interval from around 1300 to 1000 BC. These groupings appeared later in many of the classical Greek constellations.[6]

Ancient near East

The Babylonians were the first to recognize that astronomical phenomena are periodic and apply mathematics to their predictions. The oldest Babylonian star catalogues of stars and constellations date back to the beginning in the Middle Bronze Age, most notably the Three Stars Each texts and the MUL.APIN, an expanded and revised version based on more accurate observation from around 1000 BC. However, the numerous Sumerian names in these catalogues suggest that they build on older, but otherwise unattested, Sumerian traditions of the Early Bronze Age.[7]

The classical Zodiac is a product of a revision of the Old Babylonian system in later Neo-Babylonian astronomy 6th century BC. Knowledge of the Neo-Babylonian zodiac is also reflected in the Hebrew Bible. E. W. Bullinger interpreted the creatures appearing in the books of Ezekiel (and thence in Revelation) as the middle signs of the four quarters of the Zodiac,[8][9] with the Lion as Leo, the Bull as Taurus, the Man representing Aquarius and the Eagle standing in for Scorpio.[10] The biblical Book of Job also makes reference to a number of constellations, including עיש `Ayish "bier", כסיל Kĕciyl "fool" and כימה Kiymah "heap" (Job 9:9, 38:31-32), rendered as "Arcturus, Orion and Pleiades" by the KJV, but `Ayish "the bier" actually corresponding to Ursa Major.[11] The term Mazzaroth מַזָּרוֹת, a hapax legomenon in Job 38:32, may be the Hebrew word for the zodiacal constellations.

The Greeks adopted the Babylonian system in the 4th century BC. A total of twenty Ptolemaic constellations are directly continued from the Ancient Near East. Another ten have the same stars but different names.[6]

Chinese astronomy

In ancient China astronomy has had a long tradition in accurately observing celestial phenomena.[12] Star names later categorized in the twenty-eight mansions have been found on oracle bones unearthed at Anyang, dating back to the middle Shang Dynasty. These Chinese constellations are one of the most important and also the most ancient structures in the Chinese sky, attested from the 5th century BC. Parallels to the earliest Babylonian (Sumerian) star catalogues suggest that the ancient Chinese system did not arise independently.[13]

Classical Chinese astronomy is recorded in the Han period and appears in the form of three schools, which are attributed to astronomers of the Zhanguo period. The constellations of the three schools were conflated into a single system by Chen Zhuo, an astronomer of the 3rd century (Three Kingdoms period). Chen Zhuo's work has been lost, but information on his system of constellations survives in Tang period records, notably by Qutan Xida. The oldest extant Chinese star chart dates to that period and was preserved as part of the Dunhuang Manuscripts. Native Chinese astronomy flourished during the Song dynasty, and during the Yuan Dynasty became increasingly influenced by medieval Islamic astronomy (see Treatise on Astrology of the Kaiyuan Era).[14]

Traditional Chinese star maps incorporated 23 asterisms of the southern sky based on the knowledge of western star charts.[15] They were first introduced by Xu Guangqi, by the end of the Ming Dynasty, in the middle of the seventeenth century.

Indian astronomy

Some of the earliest roots of Indian astronomy can be dated to the period of Indus Valley Civilization, a Bronze Age civilisation in the northwest Indian subcontinent. Afterwards the astronomy developed as a discipline of Vedanga or one of the "auxiliary disciplines" associated with the study of the Vedas,[16] dating 1500 BC or older.The oldest known text is the Vedanga Jyotisha, dated to 1400–1200 BC[17]

As with other traditions, the original application of astronomy was thus religious. Indian astronomy was influenced by Greek astronomy beginning in the 4th century BC and through the early centuries of the Common Era, for example by the Yavanajataka and the Romaka Siddhanta, a Sanskrit translation of a Greek text disseminated from the 2nd century.[18]

Indian astronomy flowered in the 5th–6th century, with Aryabhata, whose Aryabhatiya represented the pinnacle of astronomical knowledge at the time. Later the Indian astronomy significantly influenced medieval Islamic, Chinese and European astronomy.[19] Other astronomers of the classical era who further elaborated on Aryabhata's work include Brahmagupta, Varahamihira and Lalla. An identifiable native Indian astronomical tradition remained active throughout the medieval period and into the 16th or 17th century, especially within the Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics.

Classical antiquity

There is only limited information on indigenous Greek constellations, with some fragmentary evidence being found in the Works and Days of Greek poet Hesiod, who mentioned the "heavenly bodies".[20] Greek astronomy essentially adopted the older Babylonian system in the Hellenistic era, first introduced to Greece by Eudoxus of Cnidus in the 4th century BC. The original work of Eudoxus is lost, but it survives as a versification by Aratus, dating to the 3rd century BC. The most complete existing works dealing with the mythical origins of the constellations are by the Hellenistic writer termed pseudo-Eratosthenes and an early Roman writer styled pseudo-Hyginus. The basis of western astronomy as taught during Late Antiquity and until the Early Modern period is the Almagest by Ptolemy, written in the 2nd century.

In Ptolemaic Egypt, native Egyptian tradition of anthropomorphic figures representing the planets, stars and various constellations.[21] Some of these were combined with Greek and Babylonian astronomical systems culminating in the Zodiac of Dendera, but it remains unclear when this occurred, but most were placed during the Roman period between 2nd to 4th centuries AD. The oldest known depiction of the zodiac showing all the now familiar constellations, along with some original Egyptian Constellations, Decans and Planets.[22][23] Ptolemy's Almagest remained the standard definition of constellations in the medieval period both in Europe and in Islamic astronomy.

Islamic astronomy

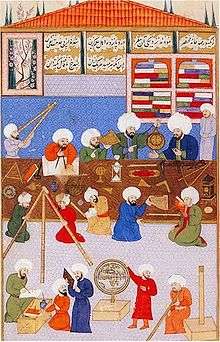

Particularly during the Islamic Golden Age (8th–15th centuries) the Islamic world experienced development in astronomy. These developments were mostly written in Arabic and took place from North Africa to Central Asia, Al-Andalus, and later in the Far East and India. It closely parallels the genesis of other Islamic sciences in its assimilation of foreign material and the amalgamation of the disparate elements of that material to create a science with Islamic characteristics. These included ancient Greek astronomy, Sassanid, and Indian works in particular, which were translated and built upon.[24] In turn, Islamic astronomy later had a significant influence on Byzantine[25] and European[26] astronomy (see Latin translations of the 12th century) as well as Chinese astronomy[27] and Malian astronomy.[28][29]

A significant number of stars in the sky, such as Aldebaran and Altair, and astronomical terms such as alidade, azimuth, and almucantar, are still referred to by their Arabic names.[30][31] A large corpus of literature from Islamic astronomy remains today, numbering approximately 10,000 manuscripts scattered throughout the world, many of which have not been read or catalogued. Even so, a reasonably accurate picture of Islamic activity in the field of astronomy can be reconstructed.[32]

Early Modern era

The skies around the South Celestial Pole are not observable from north of the equator and were never catalogued by the ancient Babylonians, Greeks, Chinese and Arabs. The modern constellations in this region were first defined during the age of exploration by Petrus Plancius, who used the records from observations of twelve new constellations made by the Dutch navigators Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser and Frederick de Houtman at the end of the sixteenth century. They were later depicted by Johann Bayer in his star atlas Uranometria of 1603.[33] Several more were created by Nicolas Louis de Lacaille in his star catalogue, published in 1756.[34]

Some modern proposals for new constellations were not successful; an example is Quadrans, eponymous of the Quadrantid meteors, now divided between Boötes and Draco in the northern sky. The classical constellation of Argo Navis was broken up into several different constellations, for the convenience of stellar cartographers.

The current list of 88 constellations recognized by the International Astronomical Union since 1922 is based on the 48 listed by Ptolemy in his Almagest in the 2nd century, with early modern modifications and additions (most importantly introducing constellations covering the parts of the southern sky unknown to Ptolemy) by Petrus Plancius (1592, 1597/98 and 1613), Johannes Hevelius (1690) and Nicolas Louis de Lacaille (1763).[35][36][37]

IAU constellations

In 1922, Henry Norris Russell aided the IAU (International Astronomical Union) in dividing the celestial sphere into 88 official constellations.[38] Where possible, these modern constellations usually share the names of their Graeco-Roman predecessors, such as Orion, Leo or Scorpius. The aim of this system is area-mapping, i.e. the division of the celestial sphere into contiguous fields.[1] Out of the 88 modern constellations, 36 lie predominantly in the northern sky, and the other 52 predominantly in the southern.

In 1930, the boundaries between the 88 constellations were devised by Eugène Delporte along vertical and horizontal lines of right ascension and declination.[39] However, the data he used originated back to epoch B1875.0, which was when Benjamin A. Gould first made his proposal to designate boundaries for the celestial sphere, a suggestion upon which Delporte would base his work. The consequence of this early date is that due to the precession of the equinoxes, the borders on a modern star map, such as epoch J2000, are already somewhat skewed and no longer perfectly vertical or horizontal.[40] This effect will increase over the years and centuries to come.

Asterisms

An asterism is a pattern of stars recognized in the Earth's night sky and may be part of an official constellation. It may also be composed of stars from more than one constellation. The stars of the main asterism within a constellation are usually given Greek letters in their order of brightness, the so-called Bayer designation introduced by Johann Bayer in 1603. A total of 1,564 stars are so identified, out of approximately 10,000 stars visible to the naked eye.[41]

The brightest stars, usually the stars that make up the constellation's eponymous asterism, also retain proper names, often from Arabic. For example, the "Little Dipper" asterism of the constellation Ursa Minor has ten stars with Bayer designation, α UMi to π UMi. Of these ten stars, six have a proper name, viz. Polaris (α UMi), Kochab (β UMi), Pherkad (γ UMi), Yildun (δ UMi), Ahfa al Farkadain (ζ UMi) and Anwar al Farkadain (η UMi).

The stars within an asterism rarely have any substantial astrophysical relationship to each other, and their apparent proximity when viewed from Earth disguises the fact that they are far apart, some being much farther from Earth than others. However, there are some exceptions: almost all of the stars[42] in the constellation of Ursa Major (including most of the Big Dipper) are genuinely close to one another, travel through the galaxy with similar velocities, and are likely to have formed together as part of a cluster that is slowly dispersing. These stars form the Ursa Major moving group.

Ecliptic coordinate systems

The idea of dividing the celestial sphere into constellations, understood as areas surrounding asterisms, is early modern. The currently-used boundaries between constellations were defined in 1930. The concept is ultimately derived from the ancient tradition of dividing the ecliptic into twelve equal parts named for nearby asterisms (the Zodiac). This defined an ecliptic coordinate system which was used throughout the medieval period and into the 18th century.

Systems of dividing the ecliptic (as opposed to dividing the celestial sphere into constellations in the modern sense) are also found in Chinese and Hindu astronomy. In classical Chinese astronomy, the northern sky is divided geometrically, into five "enclosures" and twenty-eight mansions along the ecliptic, grouped into Four Symbols of seven asterisms each. Ecliptic longitude is measured using 24 Solar terms, each of 15° longitude, and are used by Chinese lunisolar calendars to stay synchronized with the seasons, which is crucial for agrarian societies. In Hindu astronomy, the term for "lunar mansion" is nákṣatra[43] A nákṣatra is one of 27 (sometimes also 28) sectors along the ecliptic. Comparable to the zodiacal system, their names are related to the most prominent asterisms in the respective sectors. The first astronomical text that lists them is the Vedanga Jyotisha.

Dark cloud constellations

The Great Rift, a series of dark patches in the Milky Way, is more visible and striking in the southern hemisphere than in the northern. It vividly stands out when conditions are otherwise so dark that the Milky Way's central region casts shadows on the ground.[44] Some cultures have discerned shapes in these patches and have given names to these "dark cloud constellations." Members of the Inca civilization identified various dark areas or dark nebulae in the Milky Way as animals, and associated their appearance with the seasonal rains.[45] Australian Aboriginal astronomy also describes dark cloud constellations, the most famous being the "emu in the sky" whose head is formed by the Coalsack.

-

The Emu in the sky—a constellation defined by dark clouds rather than by stars. The head of the emu is the Coalsack with the Southern Cross directly above. Scorpius is to the left.

References

- 1 2 "The Constellations". IAU—International Astronomical Union. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ↑ Steele, Joel Dorman (1884). "The story of the stars: New descriptive astronomy". Science series. American Book Company: 220.

- ↑ Harbord, John Bradley; Goodwin, H. B. (1897). "Glossary of navigation: a vade mecum for practical navigators" (3rd ed.). Griffin: 142.

- ↑ "Do Constellations Ever Break Apart or Change?". NASA. Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- ↑ Origins of the ancient constellations: I. The Mesopotamian traditions, by J. H. Rogers. Journal of the British Astronomical Association, vol.108, no.1, p.9-28 1998. URL: http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1998JBAA..108....9R

- 1 2 The Origin of the Greek Constellations, by Bradley E. Schaefer. Scientific American, November 2006.

- ↑ "History of the Constellations and Star Names — D.4: Sumerian constellations and star names?". Gary D. Thompson. 21 April 2015. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ↑ E.W. Bullinger, The Witness of the Stars

- ↑ D. James Kennedy, The Real Meaning of the Zodiac.

- ↑ Richard Hinckley Allen, Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning, Vol. 1 (New York: Dover Publications, 1899, p. 213-215.) argued for Scorpio having previously been called Eagle.

- ↑ Gesenius, Hebrew Lexicon

- ↑ Needham, Volume 3, p.171

- ↑ Xiaochun Sun, Jacob Kistemaker, The Chinese sky during the Han, vol. 38 of Sinica Leidensia, BRILL, 1997, ISBN 978-90-04-10737-3, p. 18, note 9.

- ↑ Xiaochun Sun, Jacob Kistemaker, The Chinese sky during the Han, vol. 38 of Sinica Leidensia, BRILL, 1997, ISBN 978-90-04-10737-3, chapter 2, 15-36.

- ↑ Sun, Xiaochun (1997). Helaine Selin, ed. Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures. Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 910. ISBN 0-7923-4066-3.

- ↑ Sarma (2008), Astronomy in India

- ↑ Subbarayappa, B. V. (14 September 1989). "Indian astronomy: An historical perspective". In Biswas, S. K.; Mallik, D. C. V.; Vishveshwara, C. V. Cosmic Perspectives. Cambridge University Press. pp. 25–40. ISBN 978-0-521-34354-1.

- ↑ Foreign Impact on Indian Life and Culture (c. 326 B.C. to C. 300 A.D.). Satyendra Nath Naskar. Abhinav Publications, 1 January 1996 – History – 253 pages. Pages 56–57

- ↑ "Star Maps: History, Artistry, and Cartography", p. 17, by Nick Kanas, 2012

- ↑ "Stars and Constellations in Homer and Hesiod". The Annual of the British School at Athens. 1951.

- ↑ Marshall Clagett Ancient Egyptian Science: Calendars, clocks and astronomy (American Philosophical Society, 1995, p. 111.)

- ↑ Rogers, John H. (1998). "Origins of the ancient constellations: I. The Mesopotamian traditions". Journal of the British Astronomical Association 108: 9–28. Bibcode:1998JBAA..108....9R.

- ↑ Zodiac of Dendera, epitome. (Exhibition, Leic. square). J. Haddon, 1825.

- ↑ (Gingerich 1986)

- ↑ Joseph Leichter (June 27, 2009), The Zij as-Sanjari of Gregory Chioniades, Internet Archive, retrieved 2009-10-02

- ↑ Saliba (1999).

- ↑ van Dalen, Benno (2002), "Islamic Astronomical Tables in China: The Sources for Huihui li", in Ansari, S. M. Razaullah, History of Oriental Astronomy, Springer Science+Business Media, pp. 19–32, ISBN 1-4020-0657-8

- ↑ African Cultural Astronomy By Jarita C. Holbrook, R. Thebe Medupe, Johnson O. Urama

- ↑ Medupe, Rodney Thebe; Warner, Brian; Jeppie, Shamil; Sanogo, Salikou; Maiga, Mohammed; Maiga, Ahmed; Dembele, Mamadou; Diakite, Drissa; Tembely, Laya; Kanoute, Mamadou; Traore, Sibiri; Sodio, Bernard; Hawkes, Sharron (2008), "African Cultural Astronomy", Astrophysics and Space Science Proceedings, Astrophysics and Space Science Proceedings: 179–188, Bibcode:2008ASSP....6..179M, doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-6639-9_13, ISBN 978-1-4020-6638-2.

|chapter=ignored (help) - ↑ Arabic Star Names, Islamic Crescents' Observation Project, 2007-05-01, archived from the original on 2 February 2008, retrieved 2008-01-24

- ↑ Arabic in the sky, www.saudiramcoworld.org

- ↑ (Ilyas 1997)

- ↑ Ian Ridpath. "Bayer's southern star chart".

- ↑ Ian Ridpath. "Lacaille's southern planisphere".

- ↑ International Astronomical Union. "The Constellations".

- ↑ Ian Ridpath. "Constellation names, abbreviations and sizes". Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ↑ Ian Ridpath. "Star Tales – The Almagest". Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ↑ "The original names and abbreviations for constellations from 1922.". Retrieved 2010-01-31.

- ↑ "Constellation boundaries.". Retrieved 2011-05-24.

- ↑ A.C. Davenhall & S.K. Leggett, "A Catalogue of Constellation Boundary Data", (Centre de Donneés astronomiques de Strasbourg, February 1990).

- ↑ The Bright Star Catalogue lists 9,110 objects of the night sky which are visible to the naked eye (apparent magnitude of 6.5 or brighter). 9,096 of these are stars, all of them well within our galaxy.

- ↑ https://books.google.pl/books?id=z3JIQG3qP0kC&pg=PA212&lpg=PA212&dq=%22The+stars+within+a+constellation%22++proximity

- ↑ In Vedic Sanskrit, the term nákṣatra may refer to any heavenly body, or to "the stars" collectively. The classical sense of "lunar mansion" is first found in the Atharvaveda, and becomes the primary meaning of the term in Classical Sanskrit.The verbal root nákṣ means "to approach, come near".

- ↑ Rao, Joe. "A Great Week to See the Milky Way". Space. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ↑ The Incan View of the Night Sky

Further reading

Mythology, lore, history, and archaeoastronomy

- Allen, Richard Hinckley. (1899) Star-Names And Their Meanings, G. E. Stechert, New York, New York, U.S.A., hardcover; reprint 1963 as Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning, Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, New York, U.S.A., ISBN 978-0-486-21079-7 softcover.

- Olcott, William Tyler. (1911); Star Lore of All Ages, G. P. Putnam's Sons, New York, New York, U.S.A., hardcover; reprint 2004 as Star Lore: Myths, Legends, and Facts, Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, New York, U.S.A., ISBN 978-0-486-43581-7 softcover.

- Kelley, David H. and Milone, Eugene F. (2004) Exploring Ancient Skies: An Encyclopedic Survey of Archaeoastronomy, Springer, ISBN 978-0-387-95310-6 hardcover.

- Ridpath, Ian. (1989) Star Tales, Lutterworth Press, ISBN 0-7188-2695-7 hardcover.

- Staal, Julius D. W. (1988) The New Patterns in the Sky: Myths and Legends of the Stars, McDonald & Woodward Publishing Co., ISBN 0-939923-10-6 hardcover, ISBN 0-939923-04-1 softcover.

- Rogers, John H. (1998). "Origins of the Ancient Contellations: I. The Mesopotamian Traditions". Journal of the British Astronomical Association 108: 9–28. Bibcode:1998JBAA..108....9R.

- Rogers, John H. (1998). "Origins of the Ancient Contellations: II. The Mediterranean Traditions". Journal of the British Astronomical Association 108: 79–89. Bibcode:1998JBAA..108...79R.

Atlases and celestial maps

General & Nonspecialized – Entire Celestial Heavens:

- Becvar, Antonin. Atlas Coeli. Published as Atlas of the Heavens, Sky Publishing Corporation, Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S.A.; with coordinate grid transparency overlay.

- Norton, Arthur Philip. (1910) Norton's Star Atlas, 20th Edition 2003 as Norton's Star Atlas and Reference Handbook, edited by Ridpath, Ian, Pi Press, ISBN 978-0-13-145164-3, hardcover.

- National Geographic Society. (1957, 1970, 2001, 2007) The Heavens (1970), Cartographic Division of the National Geographic Society (NGS), Washington, D.C., U.S.A., two sided large map chart depicting the constellations of the heavens; as special supplement to the August 1970 issue of National Geographic. Forerunner map as A Map of The Heavens, as special supplement to the December 1957 issue. Current version 2001 (Tirion), with 2007 reprint.

- Sinnott, Roger W. and Perryman, Michael A.C. (1997) Millennium Star Atlas, Epoch 2000.0, Sky Publishing Corporation, Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S.A., and European Space Agency (ESA), ESTEC, Noordwijk, The Netherlands. Subtitle: "An All-Sky Atlas Comprising One Million Stars to Visual Magnitude Eleven from the Hipparcos and Tycho Catalogues and Ten Thousand Nonstellar Objects". 3 volumes, hardcover, in hardcover slipcase, set ISBN 0-933346-84-0. Vol. 1, 0–8 Hours (Right Ascension), ISBN 0-933346-81-6 hardcover; Vol. 2, 8–16 Hours, ISBN 0-933346-82-4 hardcover; Vol. 3, 16–24 Hours, ISBN 0-933346-83-2 hardcover. Softcover version available. Supplemental separate purchasable coordinate grid transparent overlays.

- Tirion, Wil; et al. (1987) Uranometria 2000.0, Willmann-Bell, Inc., Richmond, Virginia, U.S.A., 3 volumes, hardcover. Vol. 1 (1987): "The Northern Hemisphere to −6°", by Wil Tirion, Barry Rappaport, and George Lovi, ISBN 0-943396-14-X hardcover, printed boards (blue). Vol. 2 (1988): "The Southern Hemisphere to +6°", by Wil Tirion, Barry Rappaport and George Lovi, ISBN 0-943396-15-8 hardcover, printed boards (red). Vol. 3 (1993) as a separate added work: The Deep Sky Field Guide to Uranometria 2000.0, by Murray Cragin, James Lucyk, and Barry Rappaport, ISBN 0-943396-38-7 hardcover, printed boards (gray). 2nd Edition 2001 (black or dark background) as collective set of 3 volumes – Vol. 1: Uranometria 2000.0 Deep Sky Atlas, by Wil Tirion, Barry Rappaport, and Will Remaklus, ISBN 978-0-943396-71-2 hardcover, printed boards (blue edging); Vol. 2: Uranometria 2000.0 Deep Sky Atlas, by Wil Tirion, Barry Rappaport, and Will Remaklus, ISBN 978-0-943396-72-9 hardcover, printed boards (green edging); Vol. 3: Uranometria 2000.0 Deep Sky Field Guide by Murray Cragin and Emil Bonanno, ISBN 978-0-943396-73-6, hardcover, printed boards (teal green).

- Tirion, Wil and Sinnott, Roger W. (1998) Sky Atlas 2000.0, various editions. 2nd Deluxe Edition, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England (UK).

Northern Celestial Hemisphere & North Circumpolar Region:

- Becvar, Antonin. (1962) Atlas Borealis 1950.0, Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences (Ceskoslovenske Akademie Ved), Praha, Czechoslovakia, 1st Edition, elephant folio hardcover, with small transparency overlay coordinate grid square and separate paper magnitude legend ruler. 2nd Edition 1972 and 1978 reprint, Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences (Ceskoslovenske Akademie Ved), Prague, Czechoslovakia, and Sky Publishing Corporation, Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S.A., ISBN 0-933346-01-8 oversize folio softcover spiral bound, with transparency overlay coordinate grid ruler.

Equatorial, Ecliptic, & Zodiacal Celestial Sky:

- Becvar, Antonin. (1958) Atlas Eclipticalis 1950.0, Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences (Ceskoslovenske Akademie Ved), Praha, Czechoslovakia, 1st Edition, elephant folio hardcover, with small transparency overlay coordinate grid square and separate paper magnitude legend ruler. 2nd Edition 1974, Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences (Ceskoslovenske Akademie Ved), Prague, Czechoslovakia, and Sky Publishing Corporation, Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S.A., oversize folio softcover spiral bound, with transparency overlay coordinate grid ruler.

Southern Celestial Hemisphere & South Circumpolar Region:

- Becvar, Antonin. Atlas Australis 1950.0, Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences (Ceskoslovenske Akademie Ved), Praha, Czechoslovakia, 1st Edition, elephant folio hardcover, with small transparency overlay coordinate grid square and separate paper magnitude legend ruler. 2nd Edition, Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences (Ceskoslovenske Akademie Ved), Prague, Czechoslovakia, and Sky Publishing Corporation, Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S.A., oversize folio softcover spiral bound, with transparency overlay coordinate grid ruler.

Catalogs

- Becvar, Antonin. (1959) Atlas Coeli II Katalog 1950.0, Praha, 1960 Prague. Published 1964 as Atlas of the Heavens - II Catalogue 1950.0, Sky Publishing Corporation, Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S.A.

- Hirshfeld, Alan and Sinnott, Roger W. (1982) Sky Catalogue 2000.0, Cambridge University Press and Sky Publishing Corporation, 1st Edition, 2 volumes. LCCN 81017975 both vols., and LCCN 83240310 vol. 1. "Volume 1: Stars to Magnitude 8.0", ISBN 0-521-24710-1 (Cambridge) and 0-933346-35-2 (Sky) hardcover, ISBN 0-933346-34-4 (Sky) softcover. Vol. 2 (1985) - "Volume 2: Double Stars, Variable Stars, and Nonstellar Objects", ISBN 0-521-25818-9 (Cambridge) hardcover, ISBN 0-521-27721-3 (Cambridge) softcover. 2nd Edition (1991) with additional third author Frangois Ochsenbein, 2 volumes, LCCN 91026764. Vol. 1: ISBN 0-521-41743-0 (Cambridge) hardcover (black binding); ISBN 0-521-42736-3 (Cambridge) softcover (red lettering with Hans Vehrenberg astrophoto). Vol. 2 (1999): ISBN 0-521-27721-3 (Cambridge) softcover and 0-933346-38-7 (Sky) softcover - reprint of 1985 edition (blue lettering with Hans Vehrenberg astrophoto).

- Yale University Observatory. (1908, et al.) Catalogue of Bright Stars, New Haven, Connecticut, U.S.A. Referred to commonly as "Bright Star Catalogue". Various editions with various authors historically, the longest term revising author as (Ellen) Dorrit Hoffleit. 1st Edition 1908. 2nd Edition 1940 by Frank Schlesinger and Louise F. Jenkins. 3rd Edition (1964), 4th Edition, 5th Edition (1991), and 6th Edition (pending posthumous) by Hoffleit.

External links

| Look up constellation in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Constellations. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Constellation. |

- IAU: The Constellations, including high quality maps.

- Atlascoelestis, di Felice Stoppa.

- Star Tales origins and mythology of the constellations (Ian Ridpath)

- Celestia free 3D realtime space-simulation (OpenGL)

- Stellarium realtime sky rendering program (OpenGL)

- Strasbourg Astronomical Data Center Files on official IAU constellation boundaries

- Interactive Sky Charts (Java applets allowing navigation through the entire sky with variable star detail, optional constellation lines)

- Studies of Occidental Constellations and Star Names to the Classical Period: An Annotated Bibliography

- Table of Constellations

- Online Text: Hyginus, Astronomica translated by Mary Grant Greco-Roman constellation myths

- Neave Planetarium Adobe Flash interactive web browser planetarium and stardome with realistic movement of stars and the planets.

- Audio - Cain/Gay (2009) Astronomy Cast Constellations

- Constellation Guide Constellation facts, myths, stars and deep sky objects.

- The Greek Star-Map short essay by Gavin White

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|