Amboise conspiracy

The Amboise conspiracy, also called Tumult of Amboise, was a failed attempt by Huguenots in 1560 to gain power of France by abducting the young king Francis II and arresting Francis, Duke of Guise and his brother, the Cardinal of Lorraine. It was one of the events directly leading up to the Wars of Religion that divided France from 1562 to 1598.

Background

At the death of Henry II in 1559, the Protestants of France looked forward to a relaxation of stringent policies against their religion, but the young king, Francis II, retained his father's policy. Among the king's advisors were his wife's uncles, Francis, Duke of Guise and Charles of Guise, Cardinal of Lorraine, who through their niece exercised great influence with the King.

Plot and preparations

| ||||||

A group of provincial aristocrats decided to take matters into their own hands, by kidnapping the King and arresting the brothers Guise. Chief among the conspirators was Godefroy de Barry, seigneur de La Renaudie, of Périgord.

La Renaudie gathered round him like-minded Huguenot gentlemen representing various regions of France: Charles de Castelnau de Chalosse, Bouchard d'Aubeterre, Edme de Ferrière-Maligny (brother of Jean de Ferrieres), Captains Mazères, Cañizares, Sainte-Marie and Lignières, Jean d'Aubigné (father of Agrippa d'Aubigné) and Ardoin de Porcelet. Paulon de Mauvans, whose brother had been executed, rallied the Huguenots of Provence at Mérindol, 12 February 1560, promised 2,000 men and sent 100 to Nantes.[1] Gaspard de Coligny, later also a leading Huguenot, discouraged the nobles of Normandy from involving themselves in the plot. Leading Protestant bourgeois of Orléans, Tours and Lyon were apprised of developments.

Under the circumstances, increasingly specific rumors of the plot reached the Cardinal of Lorraine well ahead of time. On 12 February a detailed report was received through Pierre des Avenelles, a lawyer of Paris. On the 22nd, the Guises decided to transfer King and court from Blois to the château of Amboise, a more defensible site, and strengthened the castle's defenses.

The conspirators delayed their plan of action from 1 March to the 16th, but the first of the plotters' contingents arrived in the village early, and were quietly arrested from 10 March.

The tumult

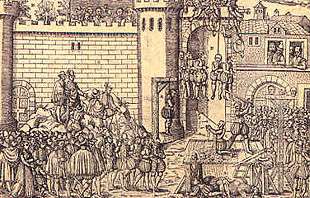

On 17 March 1560, the conspirators, led by La Renaudie, attempted to storm the Château. Though the court was thrown into panic, the plotters' forces were easily defeated. La Renaudie, caught on 19 March, was drawn and quartered and his flesh displayed at the gates of the town. In the presence of King and Queen, La Renaudie's followers - between 1,200[2] and 1,500[3] - were also killed and their corpses hung on iron hooks on the façade of the Château and from nearby trees; others were drowned in the Loire or exposed to the fury of the townspeople of Amboise.

The early colonist of Brazil, Nicolas Durand de Villegaignon became actively involved against the Protestants, and participated in the repression of the Amboise conspiracy.[4]

Aftermath

In late October 1560, Louis of Bourbon, Prince of Condé was arrested[5] on the suspicion of having been the architect of the plot but was released due to a lack of conclusive evidence. During the events he had preserved a distance from the plot but had stood at the ready at Orléans, le capitaine muet, the "silent captain" of the plotters' correspondence.[6] He was one of the principal leaders of the Huguenots during the French wars of religion.

The Edict of Amboise in 1563 ended the first phase of the French Wars of Religion.

Notes

- ↑ Pierre Miquel. Les Guerres de religion. (Club France Loisirs) 1980:211-212.

- ↑ Herodote.net: "17 mars 1560: la conjuration d'Amboise"

- ↑ Miquel 1980:213.

- ↑ "Returning to France to garner more funds and ships for the colony in Rio de Janeiro, Villegagnon found himself armed and fighting to protect the Crown at Amboise against the Huguenot conspirators." in Essays in French colonial history: proceedings of the 21st Annual Meeting of the French Colonial Society p.3-7 Michigan State University Press, 1997

- ↑ R.J. Knecht, The French Civil Wars, (Pearson Education Limited, 2000), 71.

- ↑ Pierre Miquel 1980:211; Robert Laffont. ed. Histoire et dictionnaire des guerres de religion 1998:61.