Connecting rod

In a reciprocating piston engine, the connecting rod or conrod connects the piston to the crank or crankshaft. Together with the crank, they form a simple mechanism that converts reciprocating motion into rotating motion.

Connecting rods may also convert rotating motion into reciprocating motion. Historically, before the development of engines, they were first used in this way.[1]

As a connecting rod is rigid, it may transmit either a push or a pull and so the rod may rotate the crank through both halves of a revolution, i.e. piston pushing and piston pulling. Earlier mechanisms, such as chains, could only pull. In a few two-stroke engines, the connecting rod is only required to push.[2]

Today, connecting rods are best known through their use in internal combustion piston engines, such as automotive engines. These are of a distinctly different design from earlier forms of connecting rods, used in steam engines and steam locomotives.

History

The earliest evidence for a connecting rod appears in the late 3rd century AD Roman Hierapolis sawmill. It also appears in two 6th century Eastern Roman saw mills excavated at Ephesus and Gerasa. The crank and connecting rod mechanism of these Roman watermills converted the rotary motion of the waterwheel into the linear movement of the saw blades.[3]

Sometime between 1174 and 1206, the Arab inventor and engineer Al-Jazari described a machine which incorporated the connecting rod with a crankshaft to pump water as part of a water-raising machine,[4][5] but the device was unnecessarily complex indicating that he still did not fully understand the concept of power conversion.[6]

In Renaissance Italy, the earliest evidence of a − albeit mechanically misunderstood − compound crank and connecting-rod is found in the sketch books of Taccola.[7] A sound understanding of the motion involved is displayed by the painter Pisanello (d. 1455) who showed a piston-pump driven by a water-wheel and operated by two simple cranks and two connecting-rods.[7]

By the 16th century, evidence of cranks and connecting rods in the technological treatises and artwork of Renaissance Europe becomes abundant; Agostino Ramelli's The Diverse and Artifactitious Machines of 1588 alone depicts eighteen examples, a number which rises in the Theatrum Machinarum Novum by Georg Andreas Böckler to 45 different machines.[8]

Steam engines

The first steam engines, Newcomen's atmospheric engine, was single-acting: its piston only did work in one direction and so these used a chain rather than a connecting rod. Their output rocked back and forth, rather than rotating continuously.

Steam engines after this are usually double-acting: their internal pressure works on each side of the piston in turn. This requires a seal around the piston rod and so the hinge between the piston and connecting rod is placed outside the cylinder, in a large sliding bearing block called a crosshead.

In a steam locomotive, the crank pins are usually mounted directly on one or more pairs of driving wheels, and the axle of these wheels serves as the crankshaft. The connecting rods (also called the main rods in US practice), run between the crank pins and crossheads, where they connect to the piston rods. Crossheads or trunk guides are also used on large diesel engines manufactured for marine service. (The similar rods between driving wheels are called coupling rods in British practice.)

The connecting rods of smaller steam locomotives are usually of rectangular cross-section but, on small locomotives, marine-type rods of circular cross-section have occasionally been used. Stephen Lewin, who built both locomotive and marine engines, was a frequent user of round rods. Gresley's A4 Pacifics, such as Mallard, had an alloy steel connecting rod in the form of an I-beam with a web that was only 0.375 in (9.53 mm) thick.

On Western Rivers steamboats, the connecting rods are properly called pitmans, and are sometimes incorrectly referred to as pitman arms.

Internal combustion engines

In modern automotive internal combustion engines, the connecting rods are most usually made of steel for production engines, but can be made of T6-2024 and T651-7075 aluminum alloys[9] (for lightness and the ability to absorb high impact at the expense of durability) or titanium (for a combination of lightness with strength, at higher cost) for high-performance engines, or of cast iron for applications such as motor scooters. They are not rigidly fixed at either end, so that the angle between the connecting rod and the piston can change as the rod moves up and down and rotates around the crankshaft. Connecting rods, especially in racing engines, may be called "billet" rods, if they are machined out of a solid billet of metal, rather than being cast or forged.

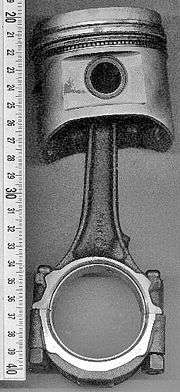

Small end and big end

The small end attaches to the piston pin, gudgeon pin or wrist pin, which is currently most often press fit into the connecting rod but can swivel in the piston, a "floating wrist pin" design. The big end connects to the bearing journal on the crank throw, in most engines running on replaceable bearing shells accessible via the connecting rod bolts which hold the bearing "cap" onto the big end. Typically there is a pinhole bored through the bearing and the big end of the connecting rod so that pressurized lubricating motor oil squirts out onto the thrust side of the cylinder wall to lubricate the travel of the pistons and piston rings. Most small two-stroke engines and some single cylinder four-stroke engines avoid the need for a pumped lubrication system by using a rolling-element bearing instead, however this requires the crankshaft to be pressed apart and then back together in order to replace a connecting rod.

Engine wear and rod length

A major source of engine wear is the sideways force exerted on the piston through the connecting rod by the crankshaft, which typically wears the cylinder into an oval cross-section rather than circular, making it impossible for piston rings to correctly seal against the cylinder walls. Geometrically, it can be seen that longer connecting rods will reduce the amount of this sideways force, and therefore lead to longer engine life. However, for a given engine block, the sum of the length of the connecting rod plus the piston stroke is a fixed number, determined by the fixed distance between the crankshaft axis and the top of the cylinder block where the cylinder head fastens; thus, for a given cylinder block longer stroke, giving greater engine displacement and power, requires a shorter connecting rod (or a piston with smaller compression height), resulting in accelerated cylinder wear.

Stress and failure

The connecting rod is under tremendous stress from the reciprocating load represented by the piston, actually stretching and being compressed with every rotation, and the load increases as the square of the engine speed increase. Failure of a connecting rod, usually called throwing a rod, is one of the most common causes of catastrophic engine failure in cars, frequently putting the broken rod through the side of the crankcase and thereby rendering the engine irreparable; it can result from fatigue near a physical defect in the rod, lubrication failure in a bearing due to faulty maintenance, or from failure of the rod bolts from a defect, improper tightening or over-revving of the engine.[10] In an unmaintained, dirty environment, a water or chemical emulsifies with the oil that lubricates the bearing and causes the bearing to fail.[11] Re-use of rod bolts is a common practice as long as the bolts meet manufacturer specifications. Despite their frequent occurrence on televised competitive automobile events, such failures are quite rare on production cars during normal daily driving. This is because production auto parts have a much larger factor of safety, and often more systematic quality control.

High-performance engines

When building a high-performance engine, great attention is paid to the connecting rods, eliminating stress risers by such techniques as grinding the edges of the rod to a smooth radius, shot peening to induce compressive surface stresses (to prevent crack initiation), balancing all connecting rod/piston assemblies to the same weight and Magnafluxing to reveal otherwise invisible small cracks which would cause the rod to fail under stress. In addition, great care is taken to torque the connecting rod bolts to the exact value specified; often these bolts must be replaced rather than reused. The big end of the rod is fabricated as a unit and cut or cracked in two to establish precision fit around the big end bearing shell. Therefore, the big end "caps" are not interchangeable between connecting rods, and when rebuilding an engine, care must be taken to ensure that the caps of the different connecting rods are not mixed up. Both the connecting rod and its bearing cap are usually embossed with the corresponding position number in the engine block.

Powder metallurgy

Recent engines such as the Ford 4.6 litre engine and the Chrysler 2.0 litre engine, have connecting rods made using powder metallurgy, which allows more precise control of size and weight with less machining and less excess mass to be machined off for balancing. The cap is then separated from the rod by a fracturing process, which results in an uneven mating surface due to the grain of the powdered metal. This ensures that upon reassembly, the cap will be perfectly positioned with respect to the rod, compared to the minor misalignments which can occur if the mating surfaces are both flat.

Compound rods

Many-cylinder multi-bank engines such as a V12 layout have little space available for many connecting rod journals on a limited length of crankshaft. This is a difficult compromise to solve and its consequence has often led to engines being regarded as failures (Sunbeam Arab, Rolls-Royce Vulture).

The simplest solution, almost universal in road car engines, is to use simple rods where cylinders from both banks share a journal. This requires the rod bearings to be narrower, increasing bearing load and the risk of failure in a high-performance engine. This also means the opposing cylinders are not exactly in line with each other.

In certain engine types, master/slave rods are used rather than the simple type shown in the picture above. The master rod carries one or more ring pins to which are bolted the much smaller big ends of slave rods on other cylinders. Certain designs of V engines use a master/slave rod for each pair of opposite cylinders. A drawback of this is that the stroke of the subsidiary rod is slightly shorter than the master, which increases vibration in a vee engine, catastrophically so for the Sunbeam Arab.

Radial engines typically have a master rod for one cylinder and multiple slave rods for all the other cylinders in the same bank.

.jpg)

The usual solution for high-performance aero-engines is a "forked" connecting rod. One rod is split in two at the big end and the other is thinned to fit into this fork. The journal is still shared between cylinders. The Rolls-Royce Merlin used this "fork-and-blade" style. A common arrangement for forked rods is for the fork rod to have a single wide bearing sleeve that spans the whole width of the rod, including the central gap. The blade rod then runs, not directly on the crankpin, but on the outside of this sleeve. The two rods do not rotate relative to each other, merely oscillate back and forth, so this bearing is relatively lightly loaded and runs as a much lower surface speed. However the bearing movement also becomes reciprocating rather than continuously rotating, which is a more difficult problem for lubrication.

A likely candidate for an extreme example of compound articulated rod design could be the complex German 24-cylinder Junkers Jumo 222 aviation engine, meant to have — unlike an X-engine layout with 24 cylinders, possessing six cylinders per bank — only four cylinders per bank, and six banks of cylinders, all liquid-cooled with five "slave" rods pinned to one master rod, for each "layer" of cylinders in its design. After building nearly 300 test examples in several different displacements, the Junkers firm's complex Jumo 222 engine turned out to be a production failure for the more advanced combat aircraft of the Third Reich's Luftwaffe which required aviation powerplants of over 1,500 kW (2,000 PS) output apiece.

See also

References

- ↑ Lyon, Robert L.; Editor. Steam Automobile Vol. 13, No. 3. SACA.

- ↑ "Steam Locomotive Glossary". www.railway-technical.com. Retrieved 2016-02-05.

- 1 2 Ritti, Grewe & Kessener 2007, p. 161:

Because of the findings at Ephesus and Gerasa the invention of the crank and connecting rod system has had to be redated from the 13th to the 6th c; now the Hierapolis relief takes it back another three centuries, which confirms that water-powered stone saw mills were indeed in use when Ausonius wrote his Mosella.

- ↑ Ahmad Y Hassan. "The Crank-Connecting Rod System in a Continuously Rotating Machine".

- ↑ Sally Ganchy; Sarah Gancher (2009), Islam and Science, Medicine, and Technology, The Rosen Publishing Group, p. 41, ISBN 1-4358-5066-1

- ↑ White, Jr. 1962, p. 170:

However, that al-Jazari did not entirely grasp the meaning of the crank for joining reciprocating with rotary motion is shown by his extraordinarily complex pump powered through a cog-wheel mounted eccentrically on its axle.

- 1 2 White, Jr. 1962, p. 113

- ↑ White, Jr. 1962, p. 172

- ↑ "What's the hardest alloy of aluminum? [Archive] - Practical Machinist - Largest Manufacturing Technology Forum on the Web". www.practicalmachinist.com. Retrieved 2016-02-05.

- ↑ "What does it mean to "throw a rod"?". Car Talk. Retrieved 2016-02-05.

- ↑ "Emerson Bearing Extreme Applications | Emerson Bearing". Emerson Bearing. Retrieved 2016-02-05.

Sources

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Connecting rods. |

- Ritti, Tullia; Grewe, Klaus; Kessener, Paul (2007), "A Relief of a Water-powered Stone Saw Mill on a Sarcophagus at Hierapolis and its Implications", Journal of Roman Archaeology 20, pp. 138–163

- White, Jr., Lynn (1962), Medieval Technology and Social Change, Oxford: At the Clarendon Press

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||