Conditional probability distribution

In probability theory and statistics, given two jointly distributed random variables X and Y, the conditional probability distribution of Y given X is the probability distribution of Y when X is known to be a particular value; in some cases the conditional probabilities may be expressed as functions containing the unspecified value x of X as a parameter. In case that both "X" and "Y" are categorical variables, a conditional probability table is typically used to represent the conditional probability. The conditional distribution contrasts with the marginal distribution of a random variable, which is its distribution without reference to the value of the other variable.

If the conditional distribution of Y given X is a continuous distribution, then its probability density function is known as the conditional density function. The properties of a conditional distribution, such as the moments, are often referred to by corresponding names such as the conditional mean and conditional variance.

More generally, one can refer to the conditional distribution of a subset of a set of more than two variables; this conditional distribution is contingent on the values of all the remaining variables, and if more than one variable is included in the subset then this conditional distribution is the conditional joint distribution of the included variables.

Discrete distributions

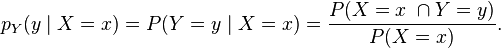

For discrete random variables, the conditional probability mass function of Y given the occurrence of the value x of X can be written according to its definition as:

Due to the occurrence of  in a denominator, this is defined only for non-zero (hence strictly positive)

in a denominator, this is defined only for non-zero (hence strictly positive)

The relation with the probability distribution of X given Y is:

Continuous distributions

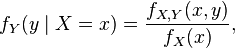

Similarly for continuous random variables, the conditional probability density function of Y given the occurrence of the value x of X can be written as

where fX,Y(x, y) gives the joint density of X and Y, while fX(x) gives the marginal density for X. Also in this case it is necessary that  .

.

The relation with the probability distribution of X given Y is given by:

The concept of the conditional distribution of a continuous random variable is not as intuitive as it might seem: Borel's paradox shows that conditional probability density functions need not be invariant under coordinate transformations.

Relation to independence

Random variables X, Y are independent if and only if the conditional distribution of Y given X is, for all possible realizations of X, equal to the unconditional distribution of Y. For discrete random variables this means P(Y = y | X = x) = P(Y = y) for all relevant x and y. For continuous random variables X and Y, having a joint density function, it means fY(y | X=x) = fY(y) for all relevant x and y.

Properties

Seen as a function of y for given x, P(Y = y | X = x) is a probability and so the sum over all y (or integral if it is a conditional probability density) is 1. Seen as a function of x for given y, it is a likelihood function, so that the sum over all x need not be 1.

Measure-Theoretic Formulation

Let  be a probability space,

be a probability space,  a

a  -field in

-field in  , and

, and  a real-valued random variable (measurable with respect to the Borel

a real-valued random variable (measurable with respect to the Borel  -field

-field  on

on  ). It can be shown that there exists[1] a function

). It can be shown that there exists[1] a function  such that

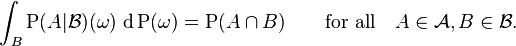

such that  is a probability measure on

is a probability measure on  for each

for each  (i.e., it is regular) and

(i.e., it is regular) and  (almost surely) for every

(almost surely) for every  . For any

. For any  , the function

, the function  is called a conditional probability distribution of

is called a conditional probability distribution of  given

given  . In this case,

. In this case,

almost surely.

Relation to conditional expectation

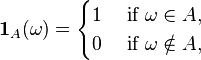

For any event  , define the indicator function:

, define the indicator function:

which is a random variable. Note that the expectation of this random variable is equal to the probability of A itself:

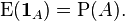

Then the conditional probability given  is a function

is a function  such that

such that  is the conditional expectation of the indicator function for A:

is the conditional expectation of the indicator function for A:

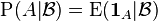

In other words,  is a

is a  -measurable function satisfying

-measurable function satisfying

A conditional probability is regular if  is also a probability measure for all ω ∈ Ω. An expectation of a random variable with respect to a regular conditional probability is equal to its conditional expectation.

is also a probability measure for all ω ∈ Ω. An expectation of a random variable with respect to a regular conditional probability is equal to its conditional expectation.

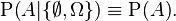

- For the trivial sigma algebra

the conditional probability is a constant function,

the conditional probability is a constant function,

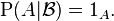

- For

, as outlined above,

, as outlined above,  .

.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Billingsley (1995), p. 439

References

- Billingsley, Patrick (1995). Probability and Measure (3rd ed.). New York: John Wiley and Sons.

![E[X | \mathcal{G}] = \int_{-\infty}^\infty x \, \mu(d x, \cdot)](../I/m/d28b3208bb961cc3a9bb0a1cf405dc6d.png)